Researchers have struggled to identify the stage of physiological complexity that endues a species with the capacity to suffer pain or distress (Greggory, 2004). Some argue that an animal must have cognitive capacity and hence be able to learn; others that evidence of a response to pain and an avoidance of aversives should be sufficient. However, the matter has been simplified for those working with and keeping animals in UK by the 2006 Animal Welfare Act (DEFRA 2006), which introduces a ‘duty of care’ on people to ensure the needs of any animal for which they are responsible. The act creates a responsibility to protect animals from suffering rather than waiting until signs of suffering occur, producing a requirement of owners and keepers to understand and provide for both the physical and emotional needs of the animals in their care. Such directives place the veterinary profession in a position where they are expected to:

But veterinary professionals need to ask themselves, despite over 10 years elapsing since the current animal welfare legislation entered the statutes, in the busy routine of the general practice, are we truly meeting the welfare requirements of our clients' pets? Do we need to provide more time in our routine discussions to talk about stress and distress?

What is stress?

Stress is an emotional and physiological response to change in an animal's environment (Mills et al, 2013). Such change is brought about by the presence of a ‘stressor’ which can be a stimulus that is either positive or negative in its nature. Hence a stress response may be one that drives an animal towards seeking proximity to a positive stressor (a response of eustress) or a stress response may drive a behaviour that is intended to create a distance between an animal and a negative stressor (a response of distress) (Carlson, 1998). Stress is associated with suffering when it creates mental distress (Gregory, 2004).

As stress is a response to the changing environment (both internal and external) (Mills, 2013), and change is an inevitable part of life, stress can be considered to be a normal and regular response, maintaining the wellbeing of the individual. Stress becomes a problem for an animal when, instead of being a temporary response to a stressor — a response that resolves the requirement for approach or avoidance — the animal is unable to resolve the problem associated with the stressor (Mills 2016). In such situations, the animal fails to cope and its welfare suffers (Greggory 2004).

Acute stress, frequent stress and chronic stress

As ‘change’ is inevitable, animal welfare benefits from preparation of an animal to relax amidst those changes that are unlikely to result in danger or excessive positive arousal — this can occur through the process of habituation (Mills et al, 2013). Without such preparation, there is the possibility that an animal will initiate a stress response to the majority of stimuli that it encounters.

If the exposure to the stressor represents a genuine threat, the stress response is intended to bring about a resolution that enhances the animal's chance of survival. Such acute stress is beneficial, short-lived and usually results in a rapid recovery (Mills, 2016). However, many domestic animals have failed to receive adequate habituation to the stressors in their environment and hence, such animals encounter stressors, both mild (e.g. low level background noises) and extreme (e.g. an approaching alarm on an ambulance), on a regular basis and throughout each day.

Each successive stress inducing episode initiates the release of stress hormones through stimulation of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic medullary adrenal system (Gray, 1987). These hormones mediate the behaviours that alter the distance from the stressor, but the HPA axis also mediates the body's responses to harm from disease, trauma, psychological distress and pain (Greggory, 2004).

Each exposure to a stressor results in the production of stress-related hormones — particularly cortisol and adrenalin — which can take a considerable period of time to degrade. With frequent exposure to stressors (whether mild or extreme) the associated stress-related hormones have insufficient time between exposures to degrade (Mills et al, 2013) resulting in an animal that may appear behaviourally recovered from an incident, but the animal's brain can continue to be exposed to high concentrations of stress-related hormones. As a consequence, such animals remain neurochemically ‘primed’ for further behavioural responses (Mills et al, 2013), but also become prone to stress-related physiological disorders (Gregory, 2004).

A lack of preparation to remain relaxed while encountering the wide range of domestic stressors that are a regular part of domestic existence, results in many pets experiencing frequent exposure to stressors. Consequently, the brains of many domestic pets are chronically exposed to the hormones associated with stress. Over time, the persistence of this state can result in chronic (enduring) distress (Mills, 2016). In addition, some owner's husbandry of their pets results in an animal that is unrelentingly exposed to stressors for a prolonged period, e.g. cats in multi-cat households, dogs lacking in social competence spending time in kennels, rabbits retained in small hutches. The resulting chronic distress can include stressrelated disease and behavioural changes such as learned helplessness and separation problems associated with changes in brain physiology resulting from prolonged exposure to stress-related hormones (Mills et al, 2013).

Emotions and stress

An emotional state is ‘any relatively brief conscious experience characterised by intense mental activity and a high degree of pleasure or displeasure’ (Cabanac, 2002).

Emotions (Box 1) mediate instinctual arousal of motivational-emotional systems in an animal's brain (Karagiannis and Heath, 2016) via stress responses to stimuli within an animal's environment and the behavioural outcome may be the same for different emotional systems.

Coping and failing to cope

Animals have an emotional life (Gregory, 2004) and exhibit behaviours motivated by emotional systems. Hence, the negative emotional states of anxiety/fear, pain and grief are part of the animal experience and their primary purpose is to enhance survival (Carlson, 2002). The more complex the animal's social and physical environment, the greater the probability of experiencing emotions and the more predictable the likelihood that animals will need to engage in behaviours associated with attempting to ‘cope’, e.g. using distance creating behaviours (cats hiding from social encounters, dogs barking at strangers) in response to anxiety/fear. Although fear/anxiety, grief and pain are negative emotions, the resultant stress drives behaviours that are expressions of an animal attempting to improve their situation (Gregory, 2004); it is when the animal is unable to engage in coping strategies and coping fails (Mills et al, 2013) that distress becomes a serious welfare issue. It is for this reason that animals benefit from permanent access to a place of safety, where stressors can be avoided, coping can be enhanced and distress can be alleviated (Mills et al, 2013).

Frustration, aggression and learned helplessness

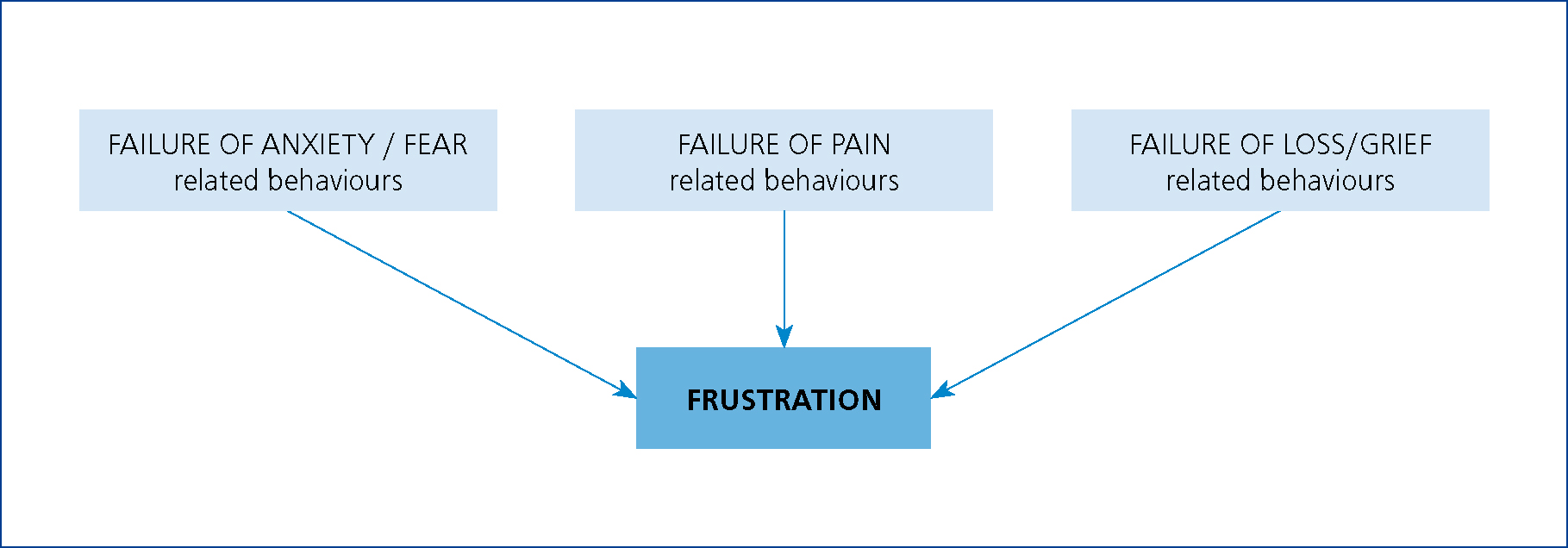

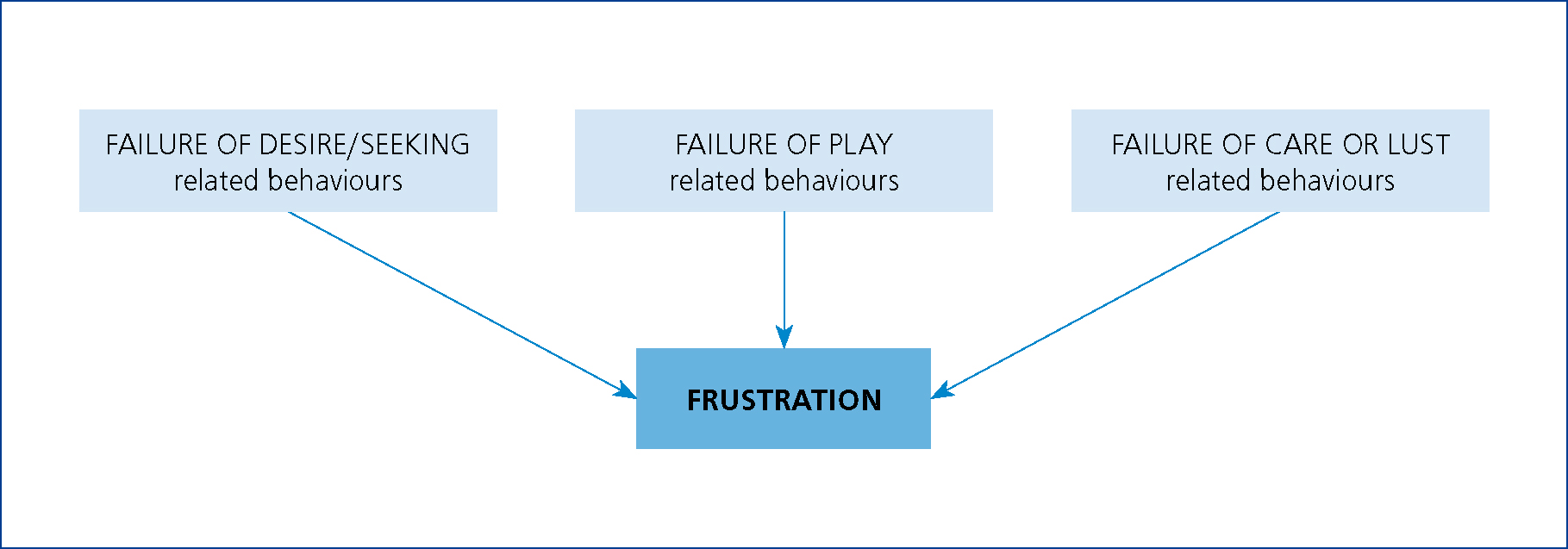

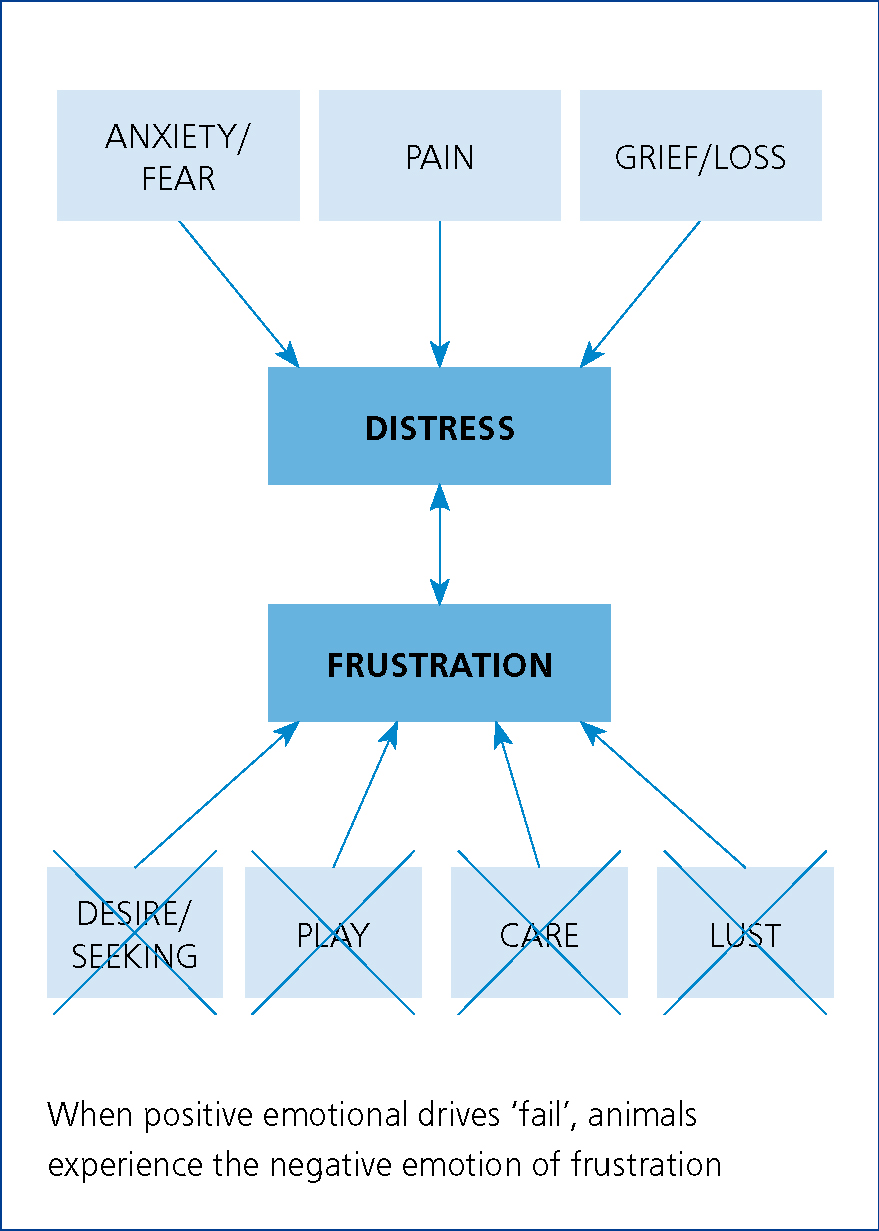

Emotions — both positive and negative — create motivations for behaviours (Carlson, 2002). Although frustration — failure — is a specific negative emotion that is associated with distress, the failure of any other emotional system to enhance coping will inevitably also lead to frustration (Figures 1–3) and further distress (Mills, 2016).

If frustration-related behaviours remain unsuccessful in resolving the animal's capacity to control its exposure to the distress-inducing stimulus, and as other behavioural strategies have proved unsuccessful in resolving the animal's emotional problem, frustration will intensify and invigorate the animal's behavioural responses (Mills et al, 2013), leading a number of professionals and owners to use the terms ‘rage’ and ‘anger’ to describe some of the resulting behaviours, particularly as intense aggression often results from frustration.

An alternative behavioural response to the invigorated behaviours associated with frustration, is for the animal to ‘give up’. This manifests as behavioural (and possibly emotional) depression (Mills et al, 2013). This state of learned helplessness occurs when an animal learns that it has no control over its environment, leading to a cessation of ongoing behaviour and a lack of behavioural response, even when alternatives are available that would alleviate distress. This state may be misinterpreted by professionals and owners as compliance or relaxation, leading to a furthering of distress.

Welfare implications in practice

The existence of emotional feelings in animals has many ethical implications for veterinary professionals and owners. The companion animal's ability to experience a range of emotions that people can empathise with (such as fear and pain) has considerable implications for the manner in which they are handled and care for. In particular, both veterinary professionals and owners have a responsibility to focus their care on the prevention of any potential for emotional suffering, not only through an awareness of an animal's ongoing emotional experience, but also through a prediction of likely emotional trauma if procedures and husbandry are not arranged with the specific intention of preventing emotional distress. In addition, the veterinary profession should be constantly aware of the likely learning associated with distressinducing situations and its implications for the animal's future capacity to cope both within the veterinary practice and the wider environment.

Conclusion

The inevitable complexity of the environment experienced by our companion animals, both at home and when visiting the veterinary practice, is an unavoidable source of potential stressors. Veterinary staff and owners have only limited capacity to change these environments to limit distress. To fulfil their responsibilities under the Animal Welfare Act veterinary professionals must therefore concentrate their efforts on providing companion animal species with appropriate preparation for coping with stressors, ensure that they can recognise individuals that are ‘failing’ to cope and subsequently provide the social and environmental changes that will assist coping. Consequently, there can be no doubt that there is a need for conversations about emotional welfare and distress to became a routine part of the consultation process. Subsequent articles on this topic will assist these conversations by focusing on the recognition and prevention of stress in specific companion animal species.