In early 2016, a 2-year-old, neutered male, domestic shorthaired cat was admitted to a first opinion veterinary surgery, presenting with haemorrhagic diar-rhoea, anorexia and pyrexia of 24–48 hours duration.

History

The patient was examined and a clinical history was gathered. The presenting symptoms included: haemorrhagic diarrhoea, a temperature of 40.8°C, lethargy and an absence of the patient's usual personality and behaviour. The veterinary surgeon (VS) admitted the cat with a guarded prognosis, as the cause was yet to be diagnosed. After admission, the following care was administered, based on the VS's prescriptions and diagnostic plan:

- Blood was sampled, and in-house pancreatic lipase and electrolyte analyses were run. The pancreatic lipase snap test presented a normal result, while the electrolyte analysis showed hypokalaemia (3.3 mmol/litre). An external haematology was sent for analysis. The results of which showed possible thrombocytopenia, although this was not conclusive due to the lack of petechial haemorrhage on examination.

- Intravenous fluid therapy (IVFT) was administered, using a 500 ml bag of crystalloid solution. A rate of 18.8 ml/hour was administered (twice maintenance), infused with a supplementary 6.3 ml of potassium chloride 15% solution for the treatment of the hypokalaemia.

- The antibiotic metronidazole 400 mg (Cresent Pharma) was prescribed at 8–10 mg/kg every 12 hours.

- The antacid famotidine (Activis) 5 mg was prescribed at rate of 0.5-1.0 mg/kg every 12–24 hours.

Please note that normal reference ranges can be found in Box 1.

Box 1.Normal ranges and equations

- Blood Potassium = 3.5–5.4 mmol/litre

- Temperature for a cat = 38.2–38.6 oC

- Intravenous fluid therapy (IVFT) equation for maintenance = 50 mls/kg/24 hours

Case description

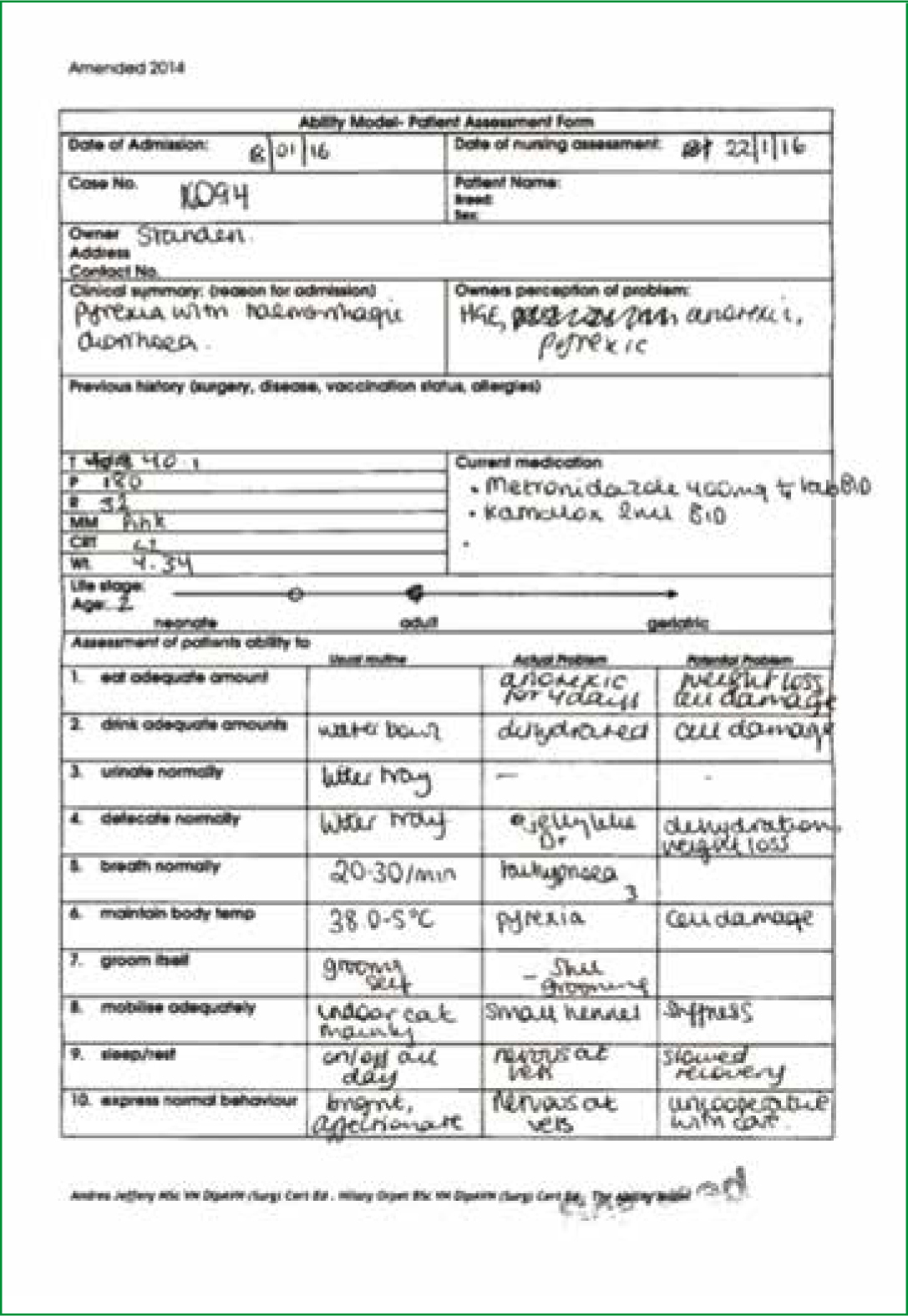

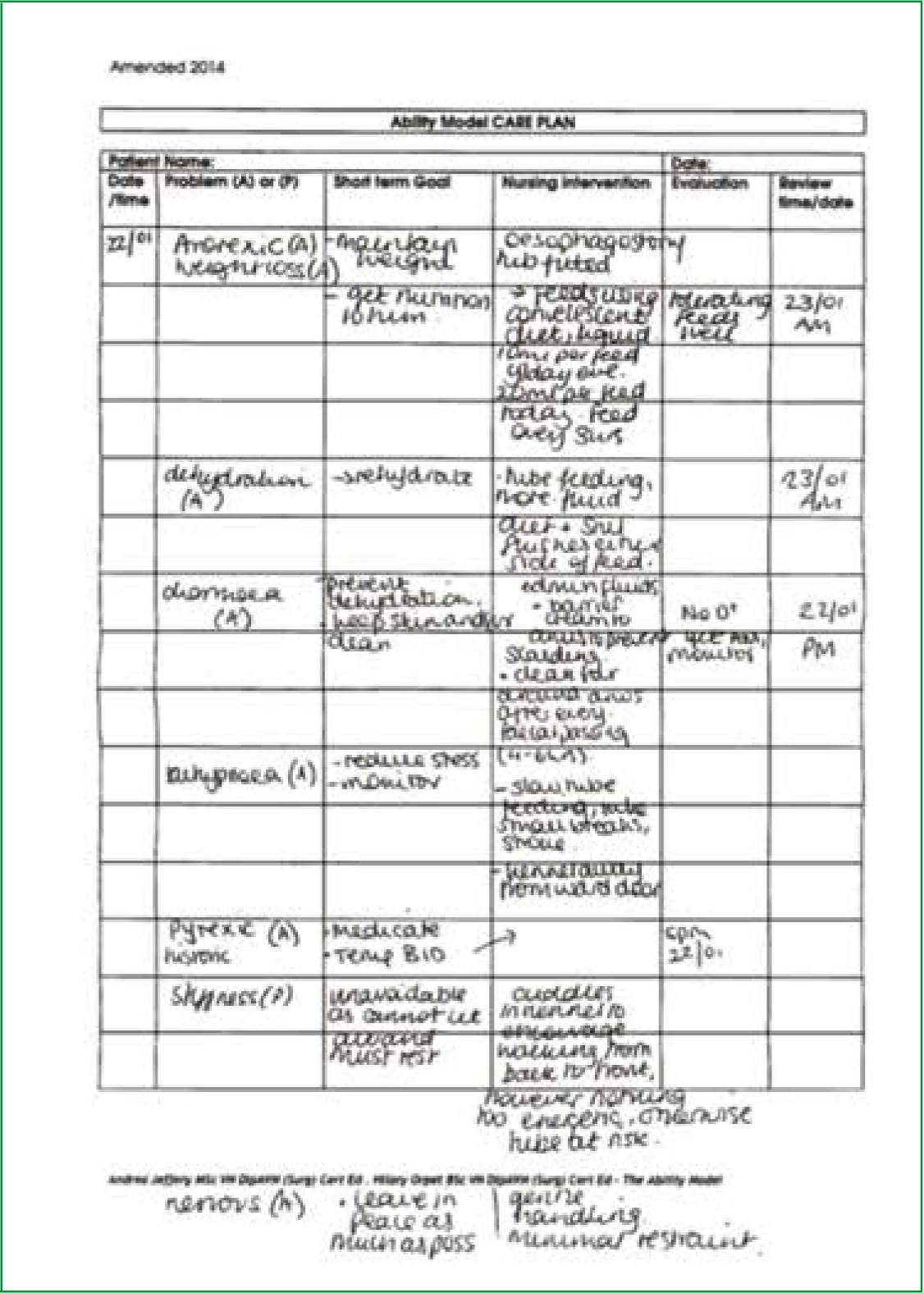

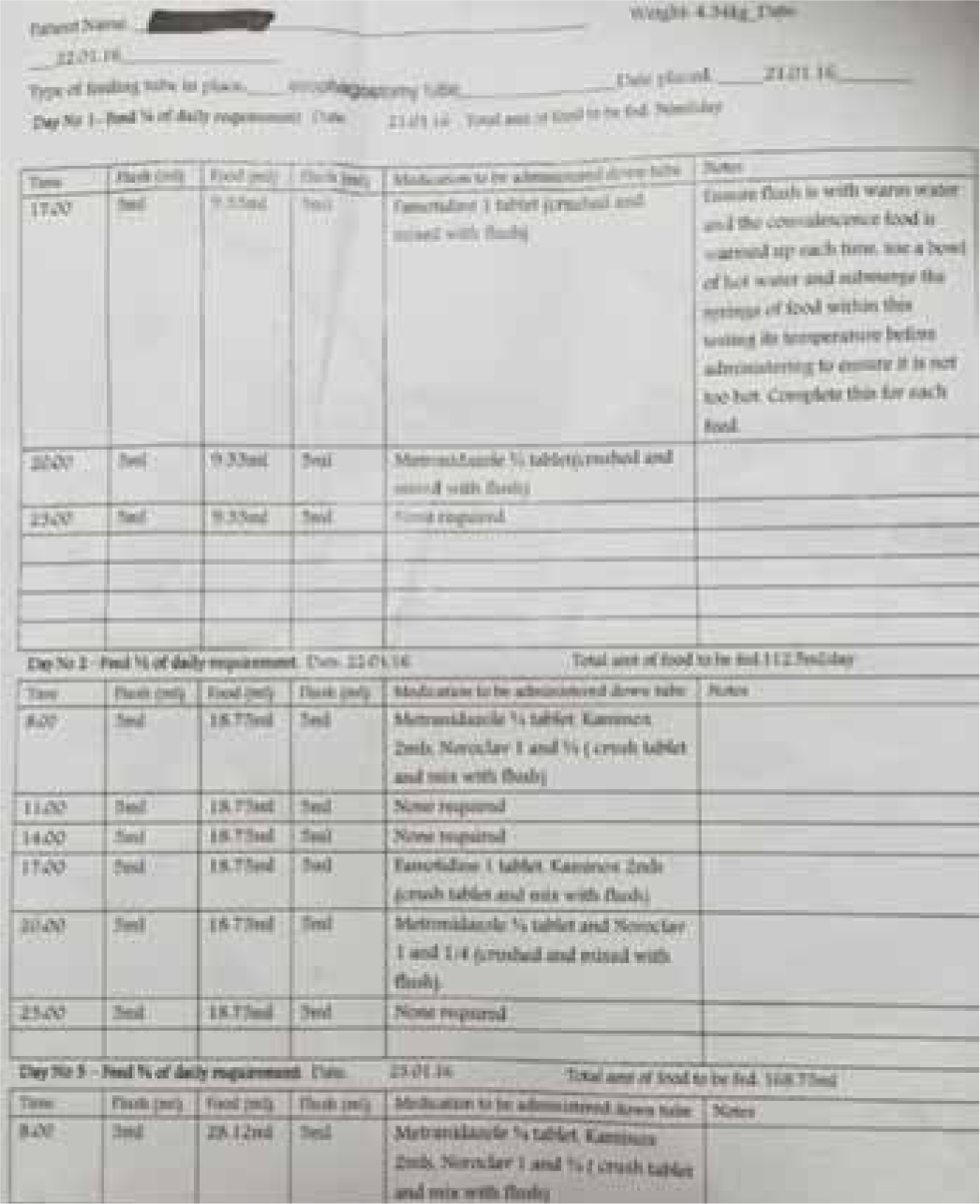

A care plan was completed by the author (Figure 1 and 2), as well as the home care plan for the owners (Figure 3). Long-term management consisted of tube feeding until solids consumed, as well as the administration of medication. Owners came into the practice every day for temperature and bandage checks, while the feeding tube was in place. Once the patient was appetent and relieved of diarrhoea and pyrexia, veterinary care was withdrawn. This took 3 to 4 weeks from admission to recovery. Table 1 summarises the care planned and delivered over the patient's 5-day hospitalisation; for the rest of the recovery period the patient was at home.

Table 1. Summary of care planned and delivered

| Nursing care plan | Observations | Vet treatment plan | Medication prescribed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day one | Patient monitoring: excretion checked every 2 hours.Temperature checked every 4 to 5 hours.Intravenous fluid therapy (IVFT) monitored Nursing care:Medication — administered by prescription.Hydration — a catheter was placed by the author, IVFT administered at twice maintenanceNutrition — small amounts of chicken offered every 3 hoursOther — prepared accommodation in peri-operative cat ward. Close monitoring required. Bedding modified due to diarrhoeal episodes, incontinence pads added. | In-house blood results showed hypokalaemia.Diarrhoeal episode on admit and an hour later. Lethargic. Anorexic. | Supportive treatment, hospitalisation overnight, re-examine in the morning.Owner happy to wait until the next morning for an update. | Metronidazole 400 mg, ¼ tablet twice a day (BID)Famotidine 5 mg once a day (SID). |

| Day two | Patient monitoring: as previous, refer to day one.Nursing care:Medication — administered by prescriptionHydration — continued IVFT, no potassium supplementationNutrition — tempted with food every 3 hours, e.g. sensitive wet, dry, chicken, fish, tunaOther — a blood sample was taken to repeat external haematology and in-house electrolytes.Catheter bandage changed as soiled. | Inappetant, pyrexia persisted (39.7–40.3°C) Potassium 4.2 mmol/litre. Hiding at the back of the kennel. | Options discussed with owner, further supportive treatment with medication and IVFT. | |

| Day three | Patient monitoring: refer to day one.Cared for oesophagostomy tube and site.Nursing care:Medication — administered as prescribedHydration — IVFT discontinued after lunchNutrition — tempted with food every 3 hours.Other — blood sample taken to assess electrolytes and to rule out infection by feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV). | No blood in the diarrhoea, but green in colour. Pyrexic (39.3°c). Inappetant. Potassum back to 3.3 mmol/litre. Deterioration observed when taken off IVFT. | Cause was still unknown, placed back on IVFT with supplemented potassium. Owner came in to discuss options. Ultrasound and oesophagostomy tube fitting to take place the following day. | Antibiotic amoxicilin (Augmentin, GlaxoSmithKlein) at 8.75 mg/kg every 8 hours Antibiotic amoxicilin injected (Synulox, Pfizer) at dosage 8.75 mg/kg every 3 to 5 days. |

| Day four | Patient monitoring: refer to day one.Cared for oesophagostomy tube and site.Nursing care:Medication — administered by prescriptionHydration — IVFT at twice maintenance Nutrition — administered 9.3 mls of feed every 3 hours (see Figure 4)Other — blood sample taken for in-house serum analysis. | Ultrasound revealed no thickening of gastrointestinal tract, no free fluid. Blood results from day three showed evidence of starvation. Only one episode of diarrhoea in the morning. | Oesophageal feeding tube placed under general anaesthetic. Continued treatment for suspected viral enteritis. | Potassium supplement Kaminox (VetPlus) at 2 mls per 4.5 kg. |

| Day five | Patient monitoring: refer to day one.Cared for oesophagostomy site and tube.Nursing care:Medication — administered by prescriptionHydration — IVFT removedNutrition — administered 18.7 mls every 3 hours. Tempted with a range of food twice a day.Other — blood sample taken for electrolyte analysis. Faecal sample taken for external analysis. | Results showed negative results for FeLV and FIV.Normal potassium, starvation parameters normalised. Interested in food, licks and sniffs observed. Diarrhoea passed 4 hours apart all day. | Continue treatment for suspected viral enteritis. Send home with feeding tube for owners to manage.Author conducted part of the discharge, demonstrating administration of medication and feeds through the tube. | Antibiotic amoxicilin (Noroclav, Norbrook) 50 mg prescribed at 12.5 mg/kg every 12 hoursSynulox injection Antiemetic Maropitant Citrate (Cerenia, Pfizer) at 1 mg/kg every 24 hours. |

Understanding the diagnostic process

True pyrexia takes place when the hypothalamus raises the thermal set point in response to an immune challenge. This differs to hyperthermia, which ensues when environmental factors impede heat loss or increase heat gain. Only a temperature exceeding 41.1°C is considered clinically dangerous in cats; values below this could be beneficial in the immune response (Flood, 2009). In this case, the presenting temperature was 40.8°C, and therefore not dangerously high. Haemorrhagic diarrhoea can be a result of haemorrhagic gastroenteritis, a potentially life-threatening condition, however as this is usually accompanied by vomiting (Hall, 2014), it is unlikely that this was the cause. As neither the diarrhoea nor the pyrexia were life threatening, the decision to treat supportively was justified during diagnostics.

To accurately support the patient, more information was sought as to its physiological status. Electrolytes and fluid are lost during episodes of diarrhoea, the quantification of which can be achieved by assessing packed cell volume (PCV) and serum electrolyte biochemistry. This was carried out in-house as a priority after admission. To an extent, this is concurrent with Battersby and Harvey (2006), who advise basic haematology, urinalysis and biochemistry analysis as diagnostic tools in patients with acute diarrhoea, a further recommendation being faecal analysis, to determine the true cause. Although the patient's faeces were analysed, the sample was taken singularly, and on day five. Singular samples have the potential to be unreliable, as they do not ensure the sampling of intermittently shed cysts, should the causative agent be parasitic. The immediate diagnostic work up highlighted potassium deficits. On a full faecal screen of the singular sample, no abnormalities were detected.

Haematology assesses the quality and quantity of a range of blood cells, assisting in determining the systemic impact of infection. The morphology and quantity of erythrocytes would indicate whether the blood lost in diarrhoea has caused anaemia, and if so, affecting the category of IVFT required. A more reliable assessment of dehydration can be performed via haematocrit analysis, where erythrocytes are counted by machine rather than assessed by eye (as for PCV). Leukocyte analysis can suggest the level of immune challenge induced by the pathogen, affecting types and dosage of drug prescribed. This patient's haematology results were normal, with the exception of a possible thrombocytopenia. As no petechial haemorrhages were seen on examination, this was not considered a conclusive result.

The cause of the patient's symptoms was still unknown, despite a better understanding of the patient's physiological state. A further blood sample was taken to eliminate or confirm infection with feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) or feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV). FeLV is initially associated with anaemia and/or immunosuppression, eventually resulting in tumours. FIV on the other hand, can manifest itself as lethargy, signs of enteritis, fever and enlargement of the lymph nodes (Hartmann, 2012). As signs of enteritis, fever and lethargy were apparent, these retroviruses needed to be ruled out. The results showed the patient was seronegative for both viruses. The ultrasound examination showed no thickening of tissue (indicative of inflammation, immune-mediated reactions), and normal physiology of kidneys, gallbladder and liver. Symptomatic treatment for suspected viral enteritis was therefore the only option, despite continual efforts to find a causative agent.

Nursing requirements

A care plan completed by the author can be found in Figures 1 and 2. In order to reduce stress in a hospital environment, it is best practice to not mix species within the same ward. It is also best practice to barrier nurse and isolate patients if there is any chance their symptoms could be caused by an infectious agent (Mosney and Devaney, 2011). Although the patient was placed in one of the feline wards, barrier nursing was not enforced. The peri-operative ward was selected, as it is directly connected to the main preparation area, making regular monitoring easier. This is different to the in-patient cat ward, which is located in an adjoining building. The downside to this choice was the proximity to dogs in the preparation area, as well as potentially sharing a ward with patients undergoing surgery. The cage was of a standard size, with a newspaper lining and a vet bed for the patient to rest on. As the patient was likely to be a long-stay inpatient, an igloo type bed would have been preferable on reflection, as this provides the patient with the ability to hide away if stressed. Standard litter was placed, as well as an incontinence pad on top of the vet bed.

Any patient with diarrhoea requires regular monitoring. This is to ensure both patient and accommodation is kept clean, and to monitor the patient's progress. Hydration status needs to be monitored as patients with diarrhoea experience ongoing fluid loss in their faecal output. This dehydration can be detected crudely by tacky mucous membranes and reduction in skin elasticity. Improvement in hydration status would manifest itself in more moist mucous membrane and increased elasticity of skin. Increased lethargy or weakness will also be clinically significant, as this could indicate deteriorating body condition and the patient would therefore require more intensive veterinary intervention.

The patient's diarrhoeal episodes were spaced roughly 4 hours apart and due to the proximity to the preparation area, were detected and cleaned promptly. Timings, colour, consistency and quantity of faeces was recorded on hospital sheets. Assisting in gauging improvement in symptoms and therefore confirming the correct treatment course. No pain scores were carried out by nursing staff, which is an oversight, as they could have been used to request pain relief, or quantifiably assess improvement in the patient's comfort. Visible improvements were seen, however, in the latter days of hospitalisation. The patient appeared brighter, resisting examination and displaying ‘wriggly’ behaviours noted on previous booster examinations.

The patient's nutritional requirements required intensive nursing, as the patient was persistently anorexic. The patient was offered warmed chicken, fish, kibble and warmed sensitive wet foods at intervals and removed if no interest was observed. Offering all flavours and textures in a short space of time, while the cat feels nauseous or painful, may create an aversion to all types of food available, leaving nothing to tempt with if the patient feels better later on (Michel, 2001). Nutritional assistance should be sought after 48 hours, as advised by Battersby and Harvey (2006), in order to support gastrointestinal mucosa, preserve blood flow and support the immune system. The oesophageal tube was placed on day four, however, long enough for the VS to be concerned about starvation, based on the external haematology results.

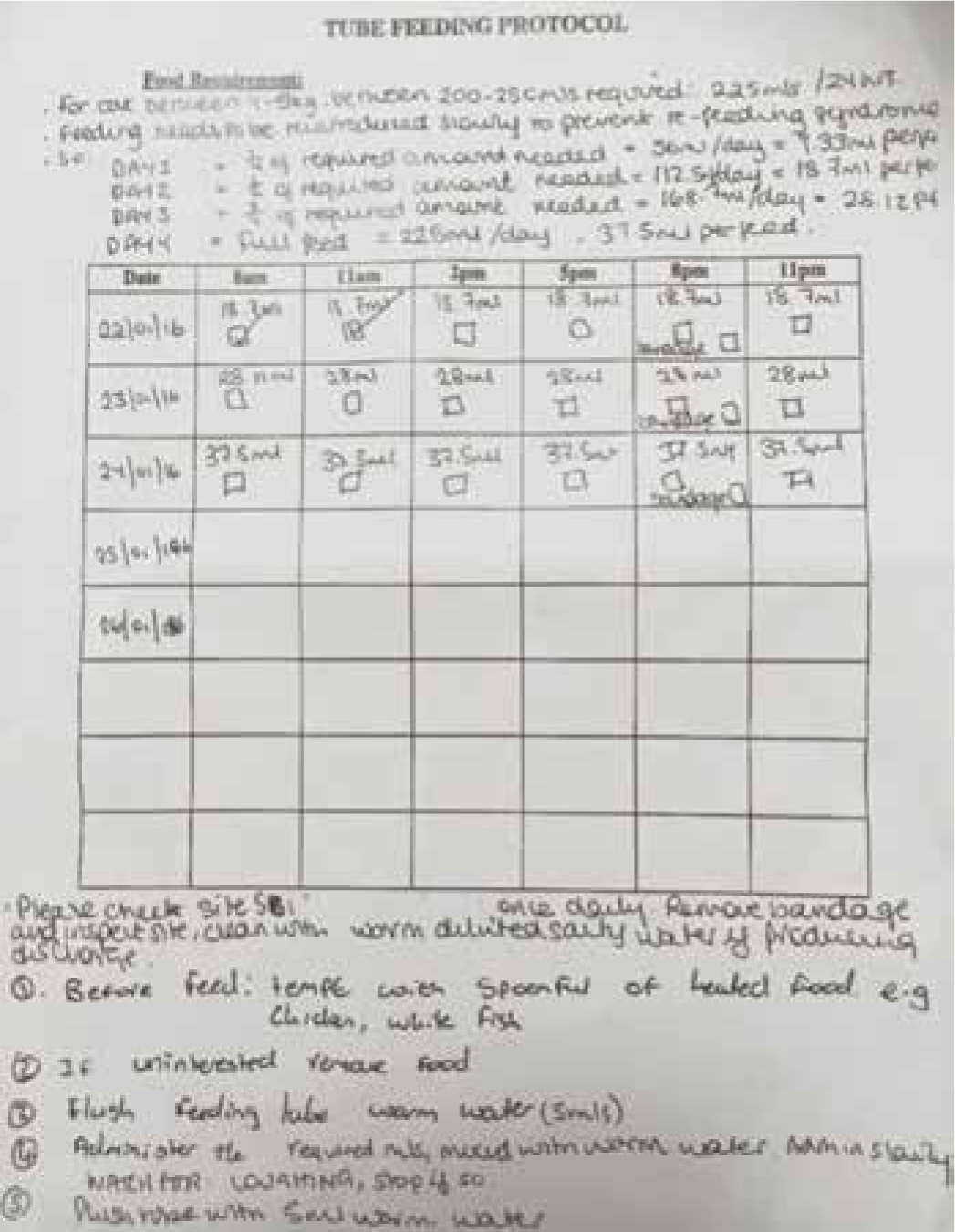

The tube feeding commenced on day four, after a refeeding plan was constructed by the author and the nursing team (found in Figure 4). This involved calculating the millilitre requirement per day based on the packet instructions (Table 2), as opposed to working out resting energy requirement (RER). Anorexic patients require slow reintroduction to nutrition, and should have 25% to 33% of their calculated intake in the first 24 hours, increasing in consistent increments every 24 hours until full required amount is reached (Perea, 2008). This method of re-feeding was carried out by both the author and the nursing team. After assisted feeding had taken place, starvation parameters improved on blood results, indicating its importance in physiological support. The feeding tube also provided a method of oral medication administration, whereby tablets were crushed and flushed down the tube with warm water. Flushing either side of the administered feeds secured the patency of the tube and assisted with oral rehydration.

Table 2. Method of calculating ml requirement for 24 hours. The patient was between 4 and 5 kg, so 225 mls over 24 hours used

| Cat | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cat's weight | Volume (ml) | Sachet (50 g) approx |

| 2kg | 100 | 1/2 |

| 3kg | 150 | 3/4 |

| 4kg | 200 | 1 |

| 5kg | 250 | 1 1/4 |

| 6kg | 300 | 1 1/2 |

| 7kg | 350 | 1 3/4 |

| 8kg | 400 | 2 |

| 9kg | 450 | 2 1/4 |

IVFT was continuously administered at twice maintenance, and was twice infused with potassium to supplement losses. The catheter remained in the same leg throughout hospitalisation, but was checked for swelling, bruising or signs of infection daily. Weil (2006) advises, however, changing the catheter site every 72 hours, to prevent bacterial colonisation at the site. Although in this case this was an oversight, no complications ensued.

The patient was discharged on day five of hospitalisation, and sent home with the oesophageal feeding tube in place. The author had a heavy involvement in the discharge, demonstrating drug and feed administration through the tube, discussing bandage care and explaining the home care plan (a copy of which can be found in Figure 3).

Conclusion

The patient's symptoms resolved 3 to 4 weeks after admission to the practice. The owners reported no diarrhoea, a willingness to eat unassisted, as well as displaying usual personality and behavioural traits. Given that the causative agent was unknown, supportive nursing care was critical to the patient's recovery. The plan in place ensured suitable hydration, the correct nutritional support and the administration of symptom easing drugs. IVFT at twice maintenance over the patients stay prevented further dehydration and replenished losses associated with diarrhoea. The regular sampling of blood also meant potassium could be added when needed. The administration of liquid feeds reversed the physiological effects of starvation, improving immune strength and cellular reserves for repair and replication. Monitoring diarrhoeal episodes, temperature and temperament throughout hospitalisation, assisted the presiding VS in making treatment decisions — tailored to the patient's stage of recovery. The careful instruction by the author at the discharge to owners meant the oesophagostomy tube was well cared for, and suitable nutrition sustained in the home environment during the later stages of recovery. Nursing care was therefore one of the driving contributors to the patient's recovery while hospitalised and once discharged.

On reflection, factors surrounding the management of the patient could have been improved on. The patient may have recovered quicker had a feeding tube been placed after 48 hours — preventing clinical starvation and associated weakening. Faecal samples could have been collected on day one and two by the nursing team, in case a pooled sample were needed later on, increasing reliability of the subsequent faecal screen. It may have also reduced patient stress to be placed in the in-patient feline ward, isolated from surgical patients. This would allow better quality rest, improve recovery time and protect other patients from nosocomial infection. To combat issues with close monitoring, interval tick boxes could have been written on the inpatient board to ensure the patient was checked minimum every 2 hours. The catheter could have been removed after 72 hours and a new catheter placed in the other cephalic vein to comply with best practice. Applications of barrier cream could also have been applied to prevent irritation of the mucous membranes at the anus (Gear and Mathie, 2011). The outcome may have been the same had these alterations been made, however the comfort of the patient may have increased, as well as the speed of recovery.

Key Points

- Supportive nursing care is essential to the management and recovery of patients requiring symptomatic treatment, especially when a specific cause is unknown

- Patients with anorexia should not go more than 48 hours without nutrition, and should not be offered all diets available during the aversion period.

- Patients with diarrhoea require regular monitoring. Consistency and colour of faeces, as well as the patient's hydration status, should be recorded in full on hospitalisation sheets.

- Pain scoring should be carried out to assess patient progress and to request pain relief, if needed.

- Patients who are suspected of being infectious must be placed in isolation from other patients, and barrier nursing should be conducted.

- As a precaution, faecal samples could be collected from day one of hospitalisation. This would mean pooled sampled could be sent for analysis later on, as opposed to singular samples.