Veterinary nurses are well aware of the fact that the body temperature of any cat or dog undergoing surgery will fall during the anaesthesia. However, most work has concentrated on temperature fluctuations during the peri-operative phase rather than in the hours post operatively (Armstrong et al, 2005). The aim of this study was to examine the level and duration of body temperature fluctuations during the intra-operative and post-operative phases, in dogs undergoing elective neutering in a general practice setting.

Literature review

Normal thermoregulation in cats and dogs occurs in response to metabolic processes of the major organs such as the liver and brain (Armstrong et al, 2005). A drop in core body temperature below 37°C is defined as hypothermia (Matsuzaki et al, 2003; Pottie et al, 2007). Hypothermia can be described as either primary or secondary. Primary hypothermia occurs from exposure to an extremely low environmental temperature whereas secondary hypothermia is a low core body temperature resulting from trauma, illness, anaesthesia or toxicity.

Secondary hypothermia in the form of intra-operative hypothermia is a known complication of surgery and anaesthesia (Bowers, 2012). The development of hypothermia during general anaesthesia can be categorised into three phases. First, an initial heat loss due to redistribution of heat between the core and the periphery; second heat loss due to radiation, convection or conduction of body heat and a reduction in metabolic rate; and finally a plateau phase where heat produced through metabolic processes matches that of heat loss (Armstrong et al, 2005).

Traditionally rectal thermometers have been used to record body temperature in veterinary patients. More recent developments include the use of auricular and oesophageal thermometers. Auricular thermometers have the advantage of being less traumatic than rectal and oesophageal methods, however, readings on both rectal and auricular thermometers will be affected by peripheral vasoconstriction during anaesthesia.

A drop in body temperature during and after anaesthesia will affect cardiovascular, neurological and immune body systems and has been shown to have a clear correlation with a delayed recovery time (Kibanda and Gurney, 2012). During the post-operative phase core temperatures will usually rise due to the reversal of the physiological processes observed during anaesthesia alongside vasoconstriction and shivering. However, the speed at which this occurs will vary between different patients.

Materials and methods

A convenience sampling approach was adopted. Only patients meeting the inclusion criteria were included. Inclusion criteria required that dogs were under 5 years of age, undergoing routine neutering and did not have any underlying medical conditions. A veterinary surgeon considered all subjects healthy and normal based on the American Society of Anaesthesiologists' Anaesthetic Risk Classification System, adapted for use in animals (ASA, 2014). Ethical approval was granted by the Faculty Ethics and Governance Committee, and all owners gave written, informed consent for their animals to be included in the study.

All dogs were given the same anaesthetic protocol, which followed standard practice procedure using standard dosages of licensed medication. Premedication with acepromazine (0.02 mg/kg) and buprenorphine (0.02 mg/kg) intramuscularly then intravenous induction with 1% propofol (4 mg/kg), endotracheal intubation and maintenance with sevoflurane in 100% oxygen. All animals were placed in dorsal recumbency on a covered electric heat pad set at 38°C.

Controllable variables were kept constant throughout their time in practice. This meant that each patient was kennelled in a stainless steel kennel with four sheets of newspaper and VetBed® (Petlife International Ltd.); the recovery ward temperature was maintained between 18°C and 22°C using domestic heating appliances and the temperature of the operating theatre was maintained at 22°C.

During recovery subjects were returned to the recovery ward, laid in lateral recumbency and covered with a blanket. Where the subject's temperature fell below 37.7°C the patient was wrapped in an additional blanket and where required, additional heat pads used.

Body temperature was recorded using an auricular thermometer (Pet Temp, Advanced Monitors). A pilot study was carried out to compare aural and rectal temperature readings; results demonstrated a maximum difference of 1°C between aural and rectal readings with auricular readings consistently lower than rectal. To ensure consistency between patients the same reader was used by the author for all recordings.

Patient details and body temperature at admission, preparation, during surgery and during recovery were recorded using a repeated measures design. The end of general anaesthesia was defined as the time when sevoflurane was switched off.

Data analysis was carried out using Microsoft Excel 2013 and Minitab 15. Due to the small sample size descriptive statistics rather than inferential were used to examine the results.

Results

Seventeen dogs were recruited to the study comprising 11 females and six males.

On admission, body temperature ranged from 37.6°C to 39.8°C with ten dogs having a temperature within the normal range of 38.3–39.2°C. On discharge body temperatures ranged from 36.6°C to 39.3°C. Body temperature of 15 of the 17 dogs dropped below 37°C at some point during or after anaesthesia. At discharge the body temperature of five dogs was still lower than 37°C.

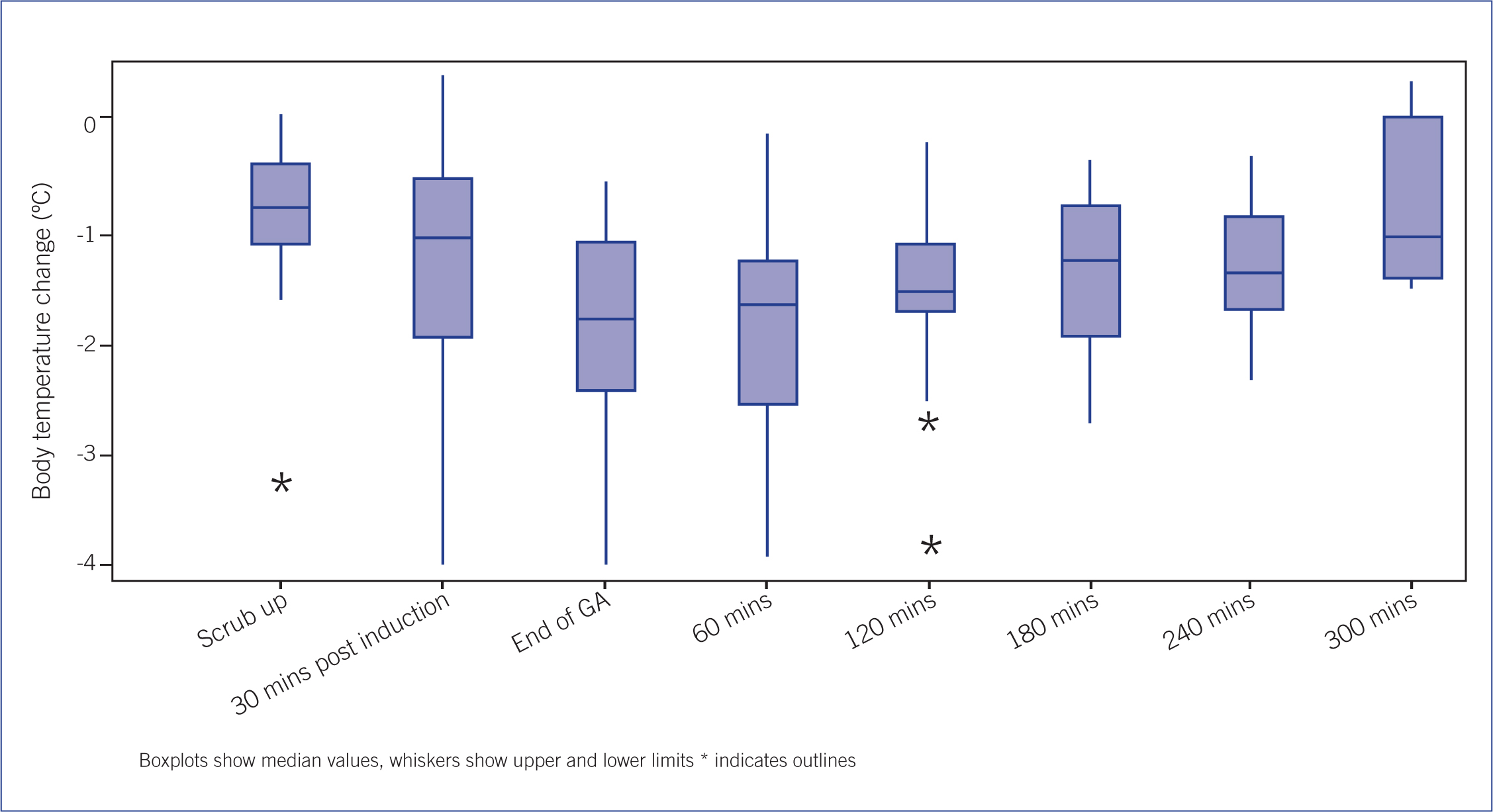

The change in body temperature during and after anaesthesia is shown in Figure 1. This illustrates a drop in the median temperature from the time of preparation for surgery through to discharge up to 6 hours after the end of general anaesthetic. Body temperature did not return to pre-anaesthesia levels during the recovery stage for 16 of the 17 patients.

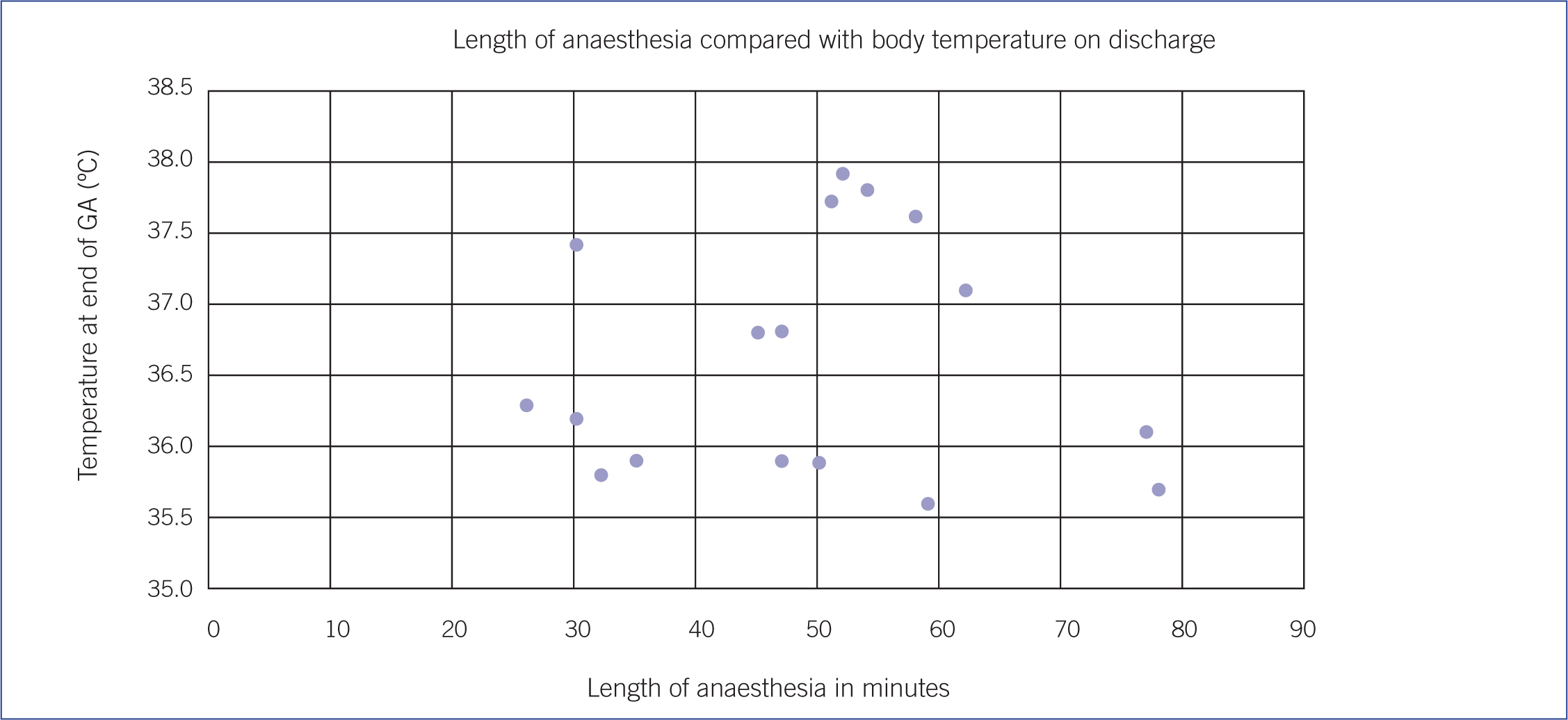

The length of general anaesthesia ranged from 26 to 78 minutes. As the length of general anaesthetic increased the core temperature of the patient on discharge was seen to increase in some patients but not all (Figure 2). The small numbers included in this study precluded further statistical analysis.

Discussion

Hypothermia is defined as a core body temperature of less than 37°C (Matsuzaki et al, 2003; Pottie et al, 2007). Peri-operative hypothermia is well recorded in humans and animals (Armstrong et al, 2005) and develops due to physiological and mechanical responses during anaesthesia and surgery. This drop in body temperature can lead to physiological problems including slower drug metabolism, alterations in ventilation and blood supply to heart, kidneys and brain. Hypothermia during the recovery phase can contribute to a delayed recovery time. Therefore every effort should be made to minimise this where possible.

Findings in this study demonstrate that body temperature can fall below normal levels during the initial stages of anaesthesia but also that it can remain lower than normal during the recovery phase. Based on the literature review it was expected that body temperature would fall during the preparation phase but rise again during the recovery phase before patients were discharged. However, it can be seen from these results that this was not the case. While data were only recorded up to 5 hours after the end of general anaesthetic, all patients were discharged with a lower body temperature than that recorded on admittance.

It can be seen that some patients had a body temperature on admittance above that considered to be the normal range. As all patients were not considered to have any underlying pathological conditions it can only be assumed that this was due to excitement.

Diaz and Becker (2010) showed that it can take up to 5 hours for thermoregulation processes to achieve equilibrium during anaesthesia and those authors suggested that animals should be hospitalised for at least 5 hours after the end of surgery.

In this current study the greatest drop in temperature was seen at the end of anaesthesia and 1 hour into recovery. The drop in temperature at the end of general anaesthesia agrees with work by Redondo et al (2012) who demonstrated that body temperature will fall during the first 3 hours of an anaesthetic. The longest anaesthetic in this study was 78 minutes. While it could be assumed that once general anaesthesia has ended and the patient is recovering body temperature will increase, this is not the case. An increase in body temperature was not recorded until 1 hour after anaesthesia had ended. This is an important point for veterinary nurses to be aware of while caring for the patients in the recovery ward.

In the authors' experiences animals undergoing routine neutering are usually discharged on the same day as surgery. Advantages include reducing patient stress and anxiety. However, as a delay in return to normal body temperature can prolong recovery, it would be advisable for body temperature to be monitored throughout the recovery phase and for practices to consider not sending dogs home until their temperature has returned to the normal range.

In this study additional heat was provided during anaesthesia by way of a heat mat, but body temperature was still seen to fall. A fall in body temperature during the initial phase of anaesthesia is not prevented by active surface warming (Armstrong et al, 2005). However, active surface warming methods such as forced air warming blankets and circulating water blankets have been shown to minimise heat loss during the second and plateau stages (Machon et al, 1999; Tan et al, 2004). Further work could be carried out to examine the time taken for body temperature to return to baseline levels where these methods have been used during anaesthesia.

The use of auricular thermometers is not, in the authors' experiences, standard in veterinary practice. Readings on both aural and rectal thermometers will be affected by perfusion and vasoconstriction (Armstrong et al, 2005; Robertson, 2007) but a comparison of different methods of temperature assessment by Southward et al (2006) did not find any significant differences between auricular and rectal temperature readings for baseline, minimum and median body temperatures. Auricular thermometers can be used as they minimise trauma and stress caused by repeated placement of the thermometer especially during the recovery phase.

Limitations

While this study has shown some interesting findings in relation to body temperature during the recovery phase it is acknowledged that the population sample size was small. Due to this only descriptive statistics could be applied to the results. Results presented are intended to highlight the importance of monitoring patients during the postoperative phase. More work is required to identify if these findings can be applied to the population as a whole.

It could also be argued that lower temperatures were recorded due to the use of the auricular thermometer. More work is required to determine the validity of auricular thermometer readings in canine patients.

Suggestions for further research

Possible areas that could be developed from this research include a comparison of rectal and auricular methods of temperature assessment; development of a similar study with a larger sample size to examine body temperature fluctuations in the recovery phase, to identify if discharging patients with a lower than normal body temperature does indeed lead to a delayed recovery period and an examination of different surgical procedures and their effect on body temperature during the recovery phase.

Conclusions

In conclusion, following anaesthesia and surgery dogs are likely to demonstrate a lower than normal body temperature and should therefore be monitored throughout the recovery period. Longer periods of hospitalisation may be required to ensure that patients are only discharged once body temperature has returned to within normal range.