A veterinary nurse can often be drawn into procedures that she/he has had little training for, without recognizing that they do have a wealth of knowledge and skill. Cataracts and ophthalmic surgery is one of the areas that cause concern for nurses.

This article will aid in veterinary nurses' understanding and knowledge of cataracts, their causes, types and management, including their removal.

The lens

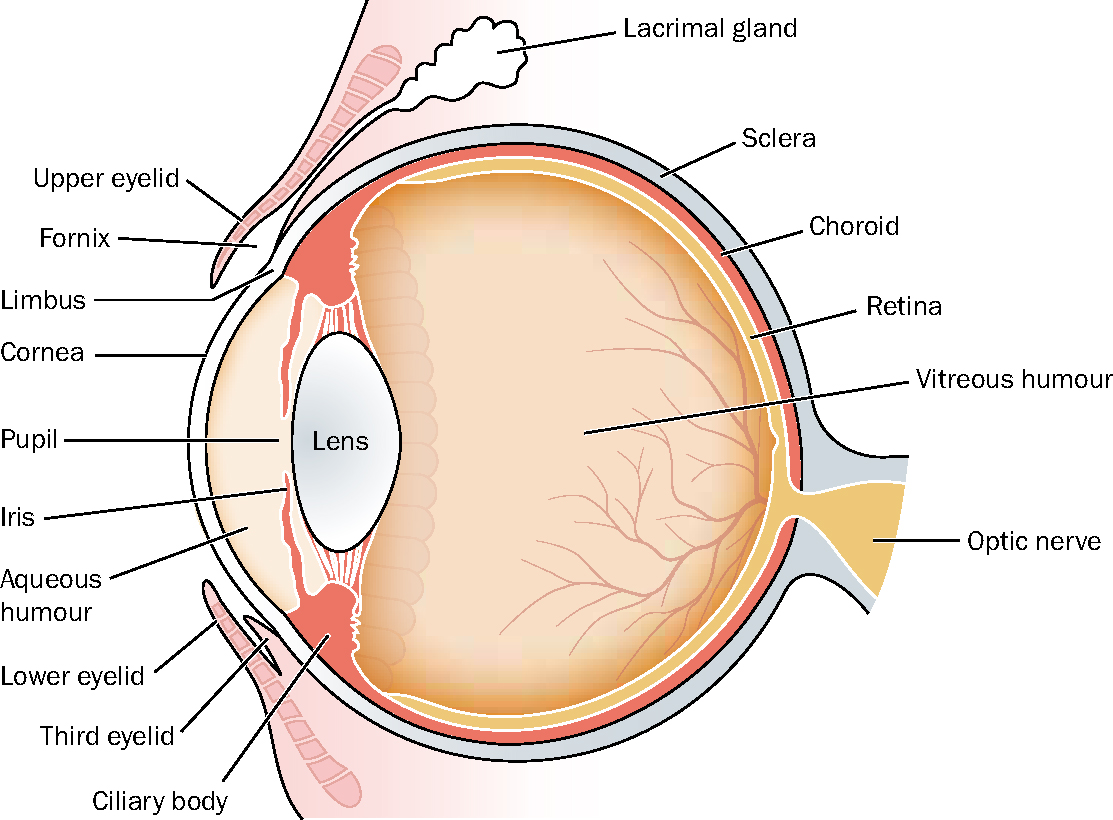

The lens is a transparent biconvex structure, surrounded by an outer capsule, sitting within the eye held by the ciliary body (Figure 1). Contraction of the ciliary muscles changes the shape of the lens, so changing its optical power. On the anterior portion of the outer capsule there is a monolayer of cuboidal epithelium that continually undergoes mitosis. On multiplying, these cells move to the equator of the lens where they become elongated, forming spindle shaped fibres (older fibres being found within the deeper section of the lens).

Cataracts

A cataract is an opacity or opacities of the lens within the eye. This opacity may affect part of the lens or the whole lens. While small areas of opacity may not affect the animal's vision, larger areas will cause blindness. Some cataract lenses can be soft, whereas others can be quite hard, depending on the stage of development.

The stage of development is directly linked to the type of cataract the patient has, rather than to age. For example, in Golden Retrievers with inherited cataracts, the cataract starts at the posterior pole of the lens and remains small for many years without effecting vision (Turner, 2005). However, in young Staffordshire Bull Terriers (6–12 months), the progression of the cataract is rapid and surgery is promptly indicated (Turner, 2005). The progression and hardness of the cataract does depend, however, on the length of time it has been present.

None of the above should be mistaken for nuclear sclerosis which occurs in all dogs over the age of 8 years and which is a natural progression of the eye during the ageing process where the lens nucleus becomes more dense. This progression results in a greyish appearance of the eye, however, the retina can still be easily examined with an ophthalmoscope. Nuclear sclerosis will be diagnosed by the veterinarian, but veterinary nurses should also view patients with this condition to familiarize themselves with the eye's natural progression during ageing.

Causes of cataract development

Hereditary (congenital and inherited)

As stated by Narfstrom et al (2000), whether or not a cataract is considered hereditary is based on whether cataracts have been seen previously in the breed. Does the cataract occurred bilaterally? Does the age and appearance of the cataract correspond with those described in the breed (Figure 2)? Is the cataract progressive (although progression may be slow in some cases)? As ‘new’ breeds become popular this can be difficult to determine. It is also suspected that hereditary cataracts are seen in some cat breeds, such as the Persian (Hoskins, 2001).

Most cataracts are believed to be recessively inherited, i.e. the gene has been passed down from the parent who showed no signs of the condition. In the affected individual (showing signs) many will progress to complete blindness (Irving, 2004). Some breeds (e.g. Staffordshire Bull Terriers, Boston Terriers, Miniature Schnauzers) have been seen to develop cataracts as early as 3 months of age (Irving, 2004; Heap, 2007). These can lead to blindness by 2–3 years of age (Irving, 2004). Some larger breeds (e.g. Golden Retriever, Labrador, Standard Poodle) despite developing an inherited cataract, do not progress to blindness, suggesting that progression to blindness may be breed specific (Irving, 2004).

Senile changes

Dogs should be examined by an ophthalmologist as early as 3 months of age; more usually eyes should be checked at 1–6 years of age to rule out progressive retinal atrophy (PRA) (Slatter, 2002), as well as other possible co-existing retinal conditions. The use of slit lamp biomicroscopy (an ophthalmic handheld instrument) will aid in differentiating between nuclear sclerosis and the development of senile cataracts (Turner, 2005). It is suggested by Irving (2004) that once the condition is diagnosed it should be monitored until it reaches the optimum time for surgery. This time will be suggested by the ophthalmologist who will take into account the patient's health status, age and condition of the cataract. Cataract surgery is not an emergency and so all patients should be prepared fully prior to surgery.

Metabolic disease

Diabetes mellitus is the more common cause of cataracts in dogs (Narfstrom et al, 2000; Irving, 2004). Cataracts in animals with diabetes will be bilateral, progress rapidly, involve the whole lens, with a clearly marked suture line separation or ‘water-cleft’ formation (Narfstrom et al, 2000). The cataract is thought to be caused by the increase in glucose in the aqueous humour. Glucose is metabolized, resulting in a higher concentration of sorbitol. Sorbital acts as an osmotic agent and draws water into the lens, causing swelling of fibres and loss of transparency. Approximately 60–70% of diabetic dogs will develop cataracts within the first year, some in 3–4 days (Irving, 2004).

Topical dexamethasone (glucocorticoid) has been seen to induce diabetes mellitus and hypertension in cats (Martin, 2009). As cats are very resistant to cataracts it is thought that the glucocorticoids were responsible for the cataracts that developed in this patient group (Martin, 2009).

Nutritional deficiencies

Cataracts have been seen in orphaned puppies fed on artificial milk replacement. This may have been a result of an imbalance in amino acids in the milk replacement (Martin, 2009). It was noticed that the lens opacity was mild and reduced as the puppies progressed to a growth diet.

Trauma and inflammation

Cataracts as a result of trauma are usually from blunt trauma or a perforating wound; the most common trauma seen will probably be from a cat claw injury. Small perforations may seal with fibrin and posterior synechiae (adhesion of the iris to the capsule of the lens), resulting in a non-progressive cataract.

In severe cases, however, the trauma progresses to complete cataract. If lens protein is released into the anterior chamber then severe uveitis (inflammation of the uvea of the eye) is seen (Narfstrom, 2004).

Radiation therapy

Cataracts are a known consequence of radiation therapy used for tumour treatment (Withrow and Vail, 2007). However, cataracts will take years to develop fully and can be successfully removed.

Toxins or drugs

Cataracts can be caused by the use of drugs (e.g. mitotic agents, enzyme inhibitors and certain metals) (Narfstrom et al, 2004), and animals of these drugs should be monitored by the veterinary surgeon.

Dog breeds predisposed to cataract development

Golden Retrievers, Boston Terriers, Staffordshire Bull Terriers, Miniature Schnauzers, Afghan Hounds and Welsh Springer Spaniels are all believed to be predisposed to cataract problems from various causes (Gelatt, 2000).

In a presentation at the New Zealand Veterinary Nursing Association Annual Conference, Heap (2007) stated that he had previously examined a litter of Miniature Schnauzers where two out of the litter of seven had juvenile cataracts. Other dogs he has commonly seen with inherited cataracts are Bichon Frise, Jack Russell Terriers. Cats do also get cataracts, but these are less common.

Classification of cataracts

The classification of cataracts is important and provides a uniform language for veterinary professionals. Cataracts can be classified in different ways:

Management of cataracts

There is no medication to prevent cataracts. Prior to cataract surgery drug therapy, such as atropine, tropicamide and phenylephrine, can be used to induce mydriasis (reflex pupillary dilation) (Irving, 2004; Cook, 2008). Surgical intervention is usually the solution and is performed on young and old dogs and involves the removal of the lens. Once the lens has been removed the cataract cannot recur. Each patient must be assessed individually for anaesthetic risk.

Cataracts are removed by extracapsular extraction (ECE) or phacoemulsification. Post lens removal it is optional whether a corrective lens (intraocular lens (IOL)) is inserted or not. IOLs will aid vision more but are not imperative. Dogs have the same degree of visual acuity as man but do not require it in their daily lives as they have the ability to utilize other senses (e.g. smell, hearing). Accommodation (the ability to change the focus from distant to near and vica versa) in the normal animal is poor and so loss of the lens results in little change. The lens represents approximately 10–20% of total optical power of the eye, the cornea being more important for visual focusing (Irving, 2004).

Extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE)

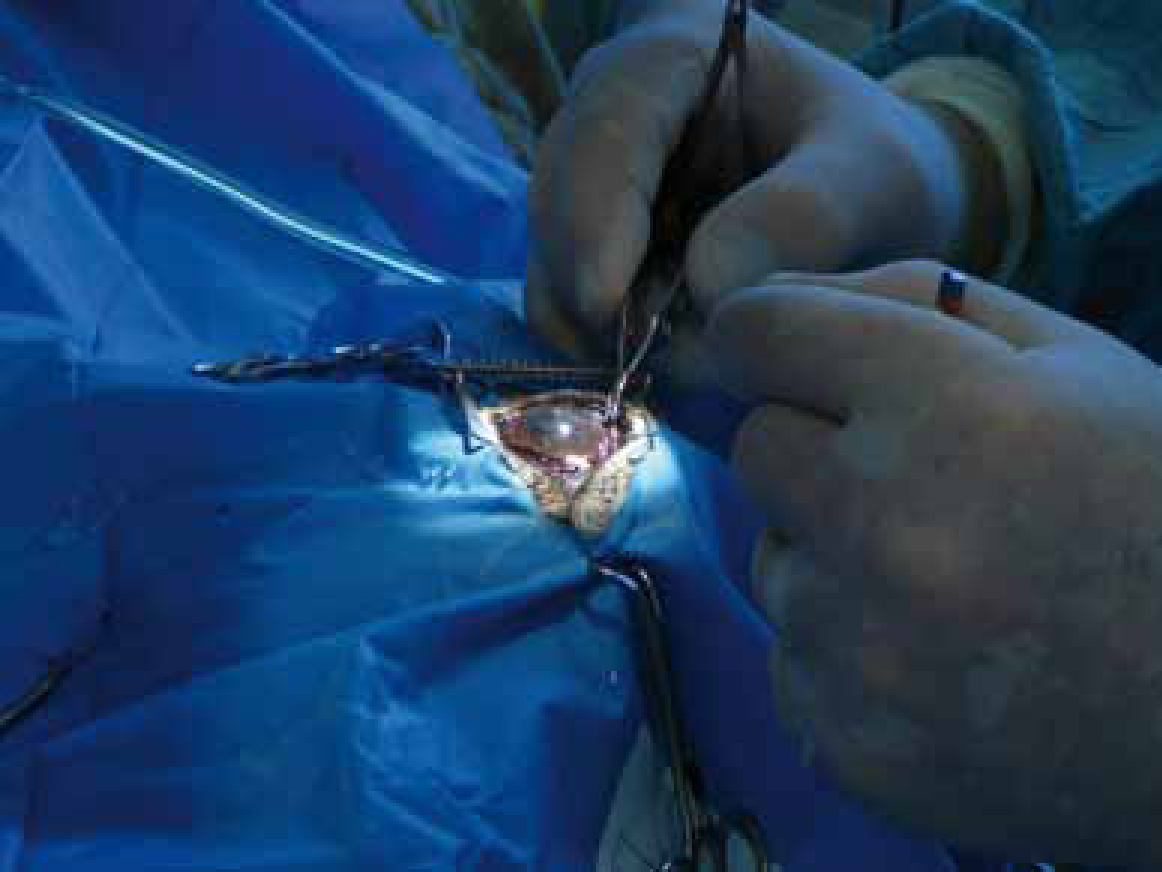

ECCE involves making an approximate 180° incision into the peripheral cornea so removal of the lens can be performed while leaving the back of the capsule (which holds the lens in place) intact (Figure 3). This technique is generally used when the lens is dense and solidified (as seen in the older animals). The eye is later re-inflated, using lactated Ringer's solution (LRS) or similar solution, if no intraocular lens (IOL) implant is inserted.

Phacoemulsification

Phacoemulsifcation uses ultrasound waves (not a laser) to emulsify and aspirate the lens. During phacoemulsification a small incision (approximately 2.8–3.2 mm in length) is made in the sclera (white of the eye) on the edge of the cornea, through the anterior lens capsule. A viscoelastic substance (thick gel-like subtance) is injected into the anterior chamber of the eye (Figure 4), this helps provide space for circulation of a balanced salt solution (LRS) during emulsification and aspiration (Cook, 2008). It also coats and protects the delicate corneal epithelium, preventing damage during surgery. Once the incision has been made through the anterior lens capsule the phacoemulsification ultrasonic (US) hand-piece tip is inserted (Figure 5) and ultrasound waves at 30 000–60 000 cycles per minute are used to break up the lens (emulsify) into tiny pieces. The phacoemulsification handpiece has both an irrigation and an aspiration port enabling the removal (aspiration) of the emulsified lens while the intraocular pressure (IOP) is maintained by irrigation. The surgeon will use an irrigation-aspiration (I/A) hand-piece for the removal of cortical material via aspiration, while maintaining IOP by irrigation. Following phacoemulsification the incision in the sclera is sutured by the veterinary surgeon (Figure 6).

This method of cataract removal causes less damage than ECE to the anterior chamber and lens fragments are completely removed. This procedure is excellent for younger animals when the lens has not hardened.

On occasion a vitrectomy is required. This is a process to remove the vitreous from within the eye that can frequently successfully restore vision. The phacoemulsification machine includes a vitrector tip which integrates irrigation, aspiration and cutting. The aspiration port is closed to the vitrector tip, thus permitting the vitrector to cut a variety of different tissues, while still maintaining IOP by irrigation.

Phacoemulsification had gained popularity over the past 10 years among veterinary ophthalmologists (Gould, 2002), and is now the treatment of choice for cataract surgery. High success rates (up to 90%) have also been reported directly, relating to the experience of the surgeon (Slatter, 2001). Success often depends not only on the surgical technique, but also on the type of cataract and the health status of the patient.

IOL implants

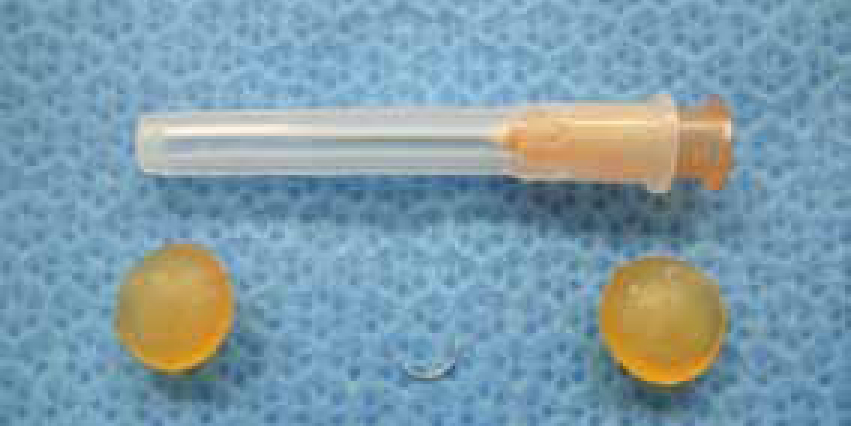

IOL implants are 6–7 mm clear, lightweight discs made of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA), acrylic or silicone. They are slightly larger than the human equivalent. They can be inserted into the empty lens capsule using a specialized cartridge and introducer, once the cataract has been removed (Cook, 2008). IOLs are a permanent implant, aiding the restoration of the animal's vision and do not require any further attention. Although the IOL would provide clearer vision an animal without artificial lens implants can still see, although vision may be less well focused.

Outcome of cataract surgery

There are few complications following canine cataract surgery, however, glaucoma and retinal detachment are the most common (Cook, 2008). Improvement from the cataract surgery may be seen by the owner immediately. Often dogs will no longer bump into furniture etc, although vision will be blurred. However, this assessment is subjective and can only accurately be assessed by the ophthalmologist. As seen in Figure 7 some patients may have good vision after 2 weeks, but generally improvement is a slow process taking many months.

Non removal of cataracts

A decision not to remove a cataract can result in a number of problems (Irving, 2004) as outlined below.

Lens induced uveitis (LIU)

Lens induced uveitis is an autoimmune disorder which erupts within the eye when lens protein material leaks from the lens through the lens capsule. LIU can result in glaucoma, adhesions within the eye, pigment disposition and luxation of the lens.

Luxation of the lens

The anterior and posterior capsules become contracted and thicken while the cataracts remains in the eye. This can result in tearing of the zonular ligaments leading to subluxation and consequently complete luxation.

Posterior capsular opacities (PCO)

PCOs occur in a cataract that has been left untreated or has been present for a very long period prior to diagnosis/surgery. PCOs from proliferation and migration of residual lens epithelial cells will form as the cataract matures. Once the lens is removed these may still cloud vision, therefore, prompt removal of cataracts is recommended. Phacoemulsification will greatly reduce the chance of PCOs (Martin, 2009).

Pigment deposition

Pigment deposition may follow cataract surgery if there has been a prolonged bout of LIU prior to surgery. They have a similar effect to PCOs.

Glaucoma

Prolonged LIU prior to cataract surgery, or if the surgery is not carried out, causes adhesions which can disturb the aqueous flow through the pupil resulting in secondary glaucoma.

Retinal detachment

The retina becomes detached from its underlying layer of supportive tissue.

Conclusion

Although nurses may not be working in a clinic that specializes in ophthalmic surgery, it is important for the nurse to understand the condition and the need for referral to an ophthalmologist. Nurses are then in a position to reassure their client and able to answer basic question. Cataract surgery is a delicate procedure (see Figure 8 to appreciate the size of the lens) but one that is very worthwhile for both patient and owner.