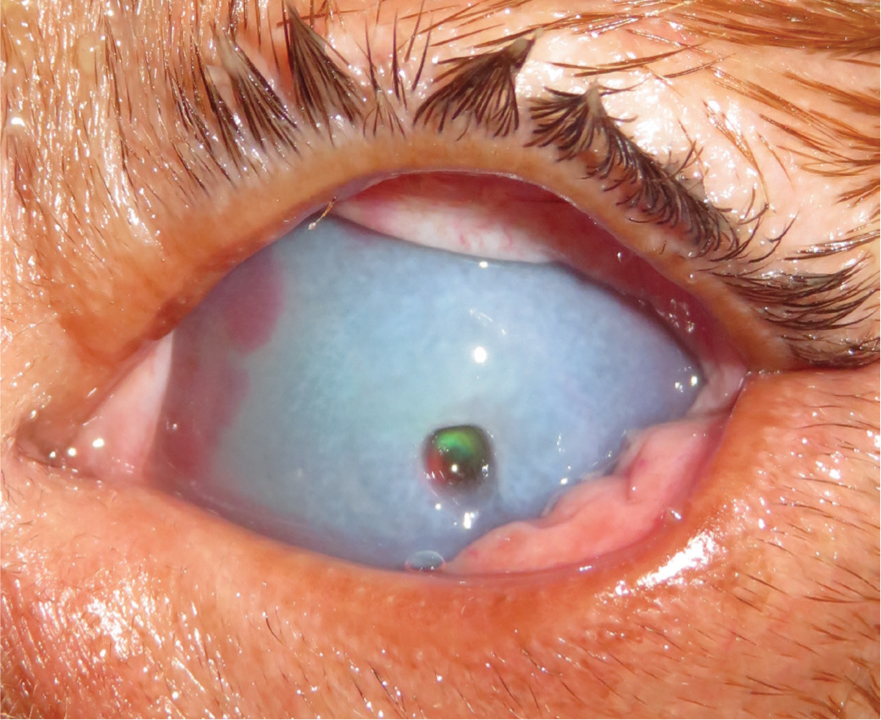

The second part of this two-part series of articles aims to discuss deep corneal ulcers including descemetoceles, a condition where the basement membrane of the endothelium (the Descemet's membrane) becomes exposed. Descemetoceles can protrude through the cornea and pose an imminent risk of corneal perforation, with leakage of aqueous humour and collapse of the anterior chamber (Figure 1, Aldridge et al, 2013). A number of factors and existing ophthalmic conditions can predispose a patient to corneal ulceration including; keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), eyelid malformation or dysfunction and various forms of trauma (Table 1). Unfortunately, with exception to traumatic ulcers, most corneal ulcerations have an underlying pathogenesis such as KCS, eyelid malformation or conditions such as entropion or distichiasis. Treatment of the underlying cause will inevitably reduce the risk of further corneal ulceration and improve the patient's quality of life.

Table 1. Causes of corneal ulcers

| Cause of corneal ulcer | Description |

|---|---|

| Tear film deficiencies | Inadequate corneal protection due to keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) can lead to corneal ulceration |

| Eyelid malformation/dysfunction | Eyelid malformation and dysfunction can lead to exposure of the cornea and corneal ulceration. Examples include: lagophthalmos, macropalpebral fissure, cranial nerve (CN) VII and CN V paralysis, ectropion |

| Endogenous cause | Endogenous causes of ulcers often include mechanical abrasion due to: entropion, distichiasis, ectopic cilia, trichiasis, eyelid masses |

| Exogenous cause | Exogenous causes include trauma such as cat scratch injuries or foreign bodies |

To recap the aetiology discussed in part one of this two-part article, the cornea is the clear, avascular anterior portion of the coating of the globe which is composed of four basic layers: the epithelium, the stroma, Descemet's membrane and the endothelium (Sanchez, 2014). The stroma is a collagen rich extracellular matrix comprised of keratocytes and proteoglycans assembled to provided strength, transparency and hydration (Chen et al, 2015), and the inner most layer, the endothelium with the Descemet's membrane, contains a single layer of cells which aid dehydration of the cornea. Corneal ulceration is described as a break in continuity of the corneal epithelium; deep corneal ulcers are a defect of the epithelium with stromal loss that may extend as far the Descemet's membrane (descemetocele). An ulcer that extends to more than two-thirds of the stomal depth should be considered an emergency.

Healing of a deep corneal ulcer is a slow process in comparison to superficial ulcers as the process involves the reformation of keratocytes, production of collagen fibres and tissue remodelling (Chen et al, 2015). In young patients, stromal healing can restore full corneal thickness with prompt diagnosis and treatment, yet adult or elderly patients may have permanent corneal changes. Remodelling of the cornea will result in corneal fibrosis and scarring, and the aims of treatment include stabilising the cornea while reducing excessive corneal vascularisation and granulation. The endothelium has limited healing capabilities and descemetoceles can be difficult to manage medically. Damage to the endothelium can result in corneal oedema and loss of transparency in the area of the descemetocele, this can lead to permanent corneal changes if excessive areas of endothelial cells are damaged. Furthermore, there are various factors that can influence the process of corneal healing and each corneal layer responds to injury in a different way, therefore, determining what type of ulcer a patient has is vital for optimal treatment.

Keratomalacia

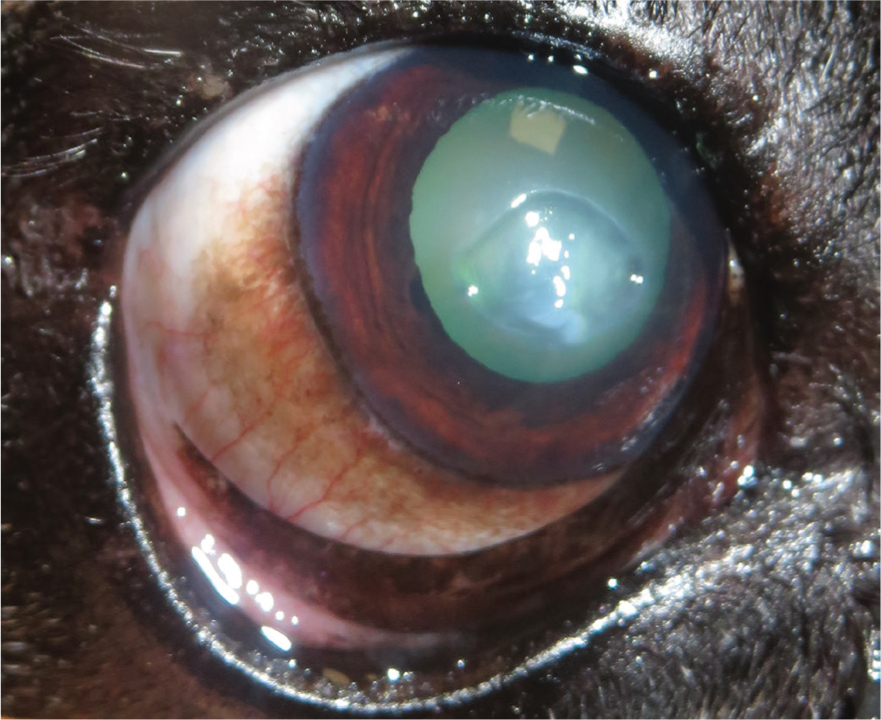

As discussed in part one of this article, an important disease process to consider with corneal ulcers is keratomalacia (Figure 2). Keratomalacia is the enzymatic destruction of the corneal stroma, there are multiple sources of the destructive enzymes including bacteria and inflammatory cells (Ketring, 2015). The appearance of infected deep corneal ulcers can vary but often have soft edges, corneal oedema with stromal thickening, and the surface can become irregular, elevated and gelatinous in appearance. Keratomalacia should always be considered an emergency even if the ulcer is shallow, as rapid melting of an ulcer can progress to corneal rupture. Ideally, all corneal ulcers should be sampled for cytology, culture and sensitivity for the evaluation of possible infection and risk of keratomalacia to allow for timely and precise management (Busse and Jaksz, 2017a).

Ophthalmic examination

Handling

The assessment of any corneal ulcer requires a thorough ophthalmic examination; a knowledgeable registered veterinary nurse (RVN) can make this easier and safer. A team approach should be used for every ophthalmic case, as owners may not have the handling techniques required for fragile eyes. Any ophthalmic patient should be handled with minimal restraint, and those handling ophthalmic patients must recognise ocular conditions to prevent further damage, preserve vision and ensure patient comfort (Busse, 2012). Canine patients are often handled by placing one hand behind the head and the other hand to steady the muzzle (Figure 3). In some brachycephalic breeds the muzzle may not be long enough to steady and a hand should be placed under the chin (Figure 4). Furthermore, brachycephalic breeds should be handled cautiously because of their predisposition to brachycephalic ocular disease and brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome (BOAS). Handling should stop if the patient becomes stressed; access to oxygen therapy should be readily available should symptoms of BOAS present.

Inadvertent pressure on the globes when retracting the eyelids and pressure around the neck when handling the patient should be avoided as this increases intraocular pressure, which could result in the rupture of a fragile eye (Busse, 2012; Presnail, 2016). If the patient is difficult to restrain or is in pain, it may be safer to perform the examination under sedation or general anaesthetic. Preliminary vision test such as menace response and pupillary light reflex should ideally be performed prior to sedation or general anaesthesia, as sedative agents can alter the menace response, pupil size, lower tear production and alter intraocular pressure (Ofri, 2015; Douet et al, 2018). Ophthalmic examination under general anaesthesia can be difficult; the veterinary surgeon may choose to use a neuromuscular blocking agent (NMBA) to centrally locate the eye and relax peri-ocular muscles to allow examination. Patients with deep corneal ulcers should not be strongly restrained and sedation or general anaesthesia should be considered for these cases.

Examination and routine tests

Where possible ophthalmological examination should include routine tests — Schirmer tear testing (STT) and the measurement of intraocular pressure. It is within the remit of the RVN's role to perform these tests and report the results to the veterinary surgeon, however, the RVN should be aware that they should not be performed if there is poor corneal integrity and risk of globe rupture. Furthermore, the STT in the contralateral eye should be performed as this may help in the diagnosis of KCS, which can be a contributing factor to corneal ulceration. RVNs can also perform further routine tests, such as menace response, pupillary light reflex, maze tests, cotton wool test (Table 2).

Table 2. Routine ophthalmic tests

| Test | Description |

|---|---|

| Menace response | The menace response test is performed by making a ‘menacing’ gesture with the hand towards the patient's eye, blink is a positive indication of functioning central and peripheral ophthalmic systems (take care to not touch the patient because excessive air movement could induce a false positive result) |

| Maze tests | An obstacle course to assess vision in daylight and dim conditions, obstacles should be adjusted to avoid memorisation and mapping |

| Cotton wool test | Cotton balls tossed into the visual field to assess the patient's visual placing response |

| Schirmer tear testing | The measurement of test tear production for the diagnosis of keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), normal tear production is between 15–25 mm/minute |

| Tonometry | The measurement of intraocular pressure for the diagnosis of glaucoma, normal intraocular pressure is between 15 mmHg and 25 mmHg |

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of a deep corneal ulcer or descemetocele requires a full ophthalmic examination and the application fluorescein to confirm the depth and width of ulceration. In a healthy cornea, the hydrophobic corneal epithelium prevents distribution of fluorescein within the stroma, however, a damaged cornea will uptake the fluorescein outlining the extent of the epithelial defect (Busse and Jaksz, 2017b). Notably, descemetoceles often appear as a crater-like defect, as there is no stroma remaining the transparent base will no longer stain. Deep ulcers and descemetoceles can be a surgical emergency because of the risk of potential globe rupture. Corneal perforation requires urgent care to prevent further ocular damage and preservation of the eye. The Seidel test may be useful to confirm corneal perforation; sterile fluorescein can be gently applied, in the case of an aqueous humour leak a diluted stream of fluorescein will be seen coming from the perforation. However, a negative Seidel test does not rule out previous perforation where the defect is sealed by fibrin or a prolapsed iris.

Treatment

Surgical intervention should be considered for any ulcer deeper than two-thirds of the corneal thickness with the aim of restoring corneal stability and removing unhealthy tissue (Busse and Jakse, 2017a). An ulcer that extends to more than two-thirds of the stromal depth should be considered an emergency; surgical intervention is often considered at this stage but some suggest intervention when 50% of the stromal depth is affected (Ledbetter and Gilger, 2013; Gogova et al, 2020). There are a number of surgical interventions that can be considered including: conjunctival graft surgery, corneoconjunctival transposition graft, corneal grafting or corneal crosslinking procedure (Table 3). The placement of a third eyelid flap could also be considered where referral is not an option and to provide emergency surgical support (Glover, 1994; Moore, 2005). Referral to an ophthalmologist should be considered for any deep ulcer where there is doubt in corneal healing and if the owners are willing.

Table 3. Common surgical interventions for deep corneal ulceration or descemetoceles

| Surgery | |

|---|---|

| Conjunctival graft | Conjunctival grafts consist of a dissected part of the conjunctiva being transposed into the corneal defect |

| Corneo-conjunctival transposition graft | Corneo-conjunctival transposition grafts consist of a pedicle of cornea attached to the limbus and the conjunctiva is slid over to repair a corneal defect |

| Corneal grafting (autologous, homologous and heterologous) | Corneal grafting involves repairing a defect with the use of tissue harvested from the adjacent normal cornea (autologous graft), from a donor animal of the same species (homologous grafts), or from a species that differs from the recipient (heterologous grafts) |

| Corneal crosslinking procedure | Corneal crosslinking is a procedure developed for the treatment of infectious and non-infectious corneal melting, the procedure uses riboflavin (Vitamin B2) to act as a photosensitiser when exposed to UV-A light, this results in biomechanical and biochemical stability of the cornea |

| Eyelid flap procedure | A procedure where the third eyelid is tacked to protect the cornea and allow the ulcer to heal (often contraindicated as it does not allow medications to be applied, for monitoring progress and the third eyelid can become inflamed and irritate the corneal epithelium) |

Medical management, with or without surgical intervention, can be intensive for the patient and owner, but it is often required for corneal stability and to reduce the risk of infection. A therapeutic approach generally includes a topical antibiotic or antifungal, ideally determined by corneal culture and sensitivity results (Ollivier, 2003), however, broad-spectrum antibiotics can be initialised prior to the availability of results (Hindley et al, 2016). Topical lubrication, systemic anti-inflammatories and/or analgesic medications are also indicated. The use of topical autologous serum could be considered in cases, or suspected cases, of keratomalacia for its collagenous inhibiting affect (Bhardwaj, 2016; Guyonnet et al, 2020). If possible autologous serum should be obtained from a donor, as inadvertent pressure on the neck and globes when obtaining blood from the patient can be detrimental to fragile eyes.

Client education and utilising registered veterinary nurses

Postoperatively the owner will need to provide further medical management and close observation at home; medication charts and colour coded medication can make intensive management easier for owners. RVNs should educate owners and demonstrate how to apply topical eye drops safely to reduce risk of further ocular problems. Prior to applying eyedrops any ocular discharge should be cleaned with cooled boiled water and cotton wool; the top eyelid can then be raised and with the other hand the eye drops can be applied in a downwards angle towards the eye. It is important that the owner is able to apply the medication safely and must not allow the nozzle of the bottle to contact the surface of the eye as this could become a source of infection and trauma. The use of an Elizabethan collar if tolerated, is highly recommended to prevent further damage and the use of a harness rather than a collar can reduce pressure on the eyes.

Educating owner on signs of pain, such as changes in demeanour, patient interference, head pressing, blepharospasm and epiphora, can decrease the need for intervention should any problems occur postoperatively and allow for appropriate pain management. RVNs are often involved in the recognition and management of pain; corneal ulcers are often a painful condition and ophthalmic surgery is thought to cause moderate to severe pain (Mathews et al, 2014). As veterinary patients are unable to verbalise the amount of pain they are experiencing, it is the responsibility of veterinary professionals to recognise and act on the signs of pain (Bloor and Allan, 2017). Ophthalmic pain is often overlooked by both veterinary professionals and pet owners; the demonstration of ocular pain is species and patient specific and can often be difficult to assess (Knott, 2019). Corneal ulcers often present with signs of pain including: blepharospasm, protrusion of the third eyelid, miosis, conjunctival hyperaemia and epiphora. Although, the signs of pain will often vary between depth of ulcers, it is important to note that patients that develop a descemetocele will often become less painful because of the depth of the ulcer and lack of corneal nerve endings. Owners will often report an improvement even though the ulcer has progressed into a descemetocele, emphasising the importance of timely reexamination. It is vital than RVNs are able to recognise the signs of ophthalmic pain as they are often overlooked.

RVNs play a vital role in client education and supporting owners through the treatment process of corneal ulceration. Providing thorough information in layman's terms will allow the owner to understand the aim of medical or surgical therapies and allow the owner to safely handle their pet and administer the oral and topical medication effectively. The decision to whether a deep corneal ulcer should be treated medically is based mainly on the depth of the defect and the presence of keratomalacia; however, other factors such as the patient's temperament, owner compliance and financial situation should all be considered to create a suitable care plan. Some patients with corneal ulcerations will be hospitalised for medical management as the frequency of topical medication can be up to every hour and frequent monitoring of the corneal integrity is required. Although management at home is possible with routine re-examination and support from an RVN, the re-examination frequency is often determined by the type of ulcer and the risk of keratomalacia.

Brachycephalic breeds

Brachycephalic breeds such as Bulldogs, Pugs and Shih Tzus have become increasingly popular, and as their levels of ownership has increased, their presentation in veterinary practice has correlated. Research from the Royal Veterinary College (RVC) has shown that brachycephalic breeds are 11 times more susceptible to corneal ulcerative disease as a result of chronic corneal exposure when compared with non-brachycephalic breeds (Packer, 2015). The study found that the most commonly diagnosed breed with corneal ulceration was the Pug, and dogs with nasal fold were nearly five times more likely to be affected by corneal ulcers than those without. Furthermore, brachycephalic ocular syndrome (BOS), a disease of shortskulled breeds where anatomical differences of the shape and positioning of the eyes are present, often leads to further ocular problems and contributes to the risk of corneal ulceration (Maggs, 2008). The traits of BOS include macroblepharon or excessively long palpebral fissures and possible lagophthalmos, a condition in which the eyelid cannot close completely, both compromise the normal lubrication of the eyes and the ocular coverage (Costa et al, 2021); and with decreased corneal sensitivity, which is often reported in brachycephalic breeds, the eyes are more prone to chronic exposure, resulting in a wide variety of problems including trauma, superficial keratitis and ulceration (Gelatt and Whitley, 2011). This information is important to note as RVNs are increasingly involved with improving the health and welfare of brachycephalic breeds (Campbell, 2020). An awareness of why brachycephalic breeds differ from non-brachycephalic breeds and a basic understanding of the anatomical and physiological differences allows the RVN to provide a superior level of care and educate owners of brachycephalic breeds on long-term ophthalmic management.

Conclusion

Corneal ulceration is one of the most common ocular problems presented in first opinion practice; with a variety of aetiologies, it is important that veterinary professionals have a thorough understanding of corneal ulcers and their presentation, to allow for timely and appropriate management. Client education is key in cases of corneal ulceration, as owners often play a vital role in providing medical management and recognising ophthalmic pain. RVNs can be used throughout the process of managing corneal ulceration, including assisting in ophthalmic examinations, creating nursing care plans and client education.

KEY POINTS

- Corneal ulceration is one of the most common ocular problems, knowledge of the types of ulcer and the disease processes involved is key for appropriate management and holistic nursing care.

- Ocular examination requires a team approach from both the veterinary nurse and veterinary surgeon.

- Corneal ulcers can be difficult for owners to manage — veterinary nurses can support owners through the treatment processes and educate owners on preventing ophthalmic disease.