Otitis extema is an acute or chronic inflammation of the external ear canal. It is a common clinical finding, with a prevalence of about 10 to 20% in dogs and 2 to 6% in cats (Angus, 2004; Saridomichelakis et al, 2007). A number of factors may be involved in its development, and primary causes, predisposing factors and perpetuating factors need to be considered. Primary causes are those that can directly induce inflammation and cause disease in a normal ear (Table 1). Predisposing factors by themselves will not cause otitis externa, but increase the likelihood of an inflammation developing by altering the normal structure or environment in the ear canal (Table 2). Perpetuating factors such as secondary infections develop as a consequence of inflammation and maintain inflammation even if the primary factor has resolved (Table 3).

| Hypersensitivity |

|

| Parasites |

|

| Foreign bodies |

|

| Keratinisation disorders |

|

| Autoimmune diseases |

|

| Endocrine diseases |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

| Anatomical configuration |

|

| Excessive moisture |

|

| Obstruction |

|

| Systemic immunosuppression |

|

| Bacteria |

|

| Yeast |

|

| Otits media | |

| Chronic inflammation |

|

Only addressing the secondary infections will not always lead to good control in the long term, and recurrence may occur. Therefore the primary cause needs to be determined and addressed when possible, in order to prevent the development of chronic disease and irreversible changes caused by chronic inflammation.

Otic pruritus or pain is the most common clinical sign of otitis externa. Head shaking, rubbing or ear scratching may be seen, occasionally leading to aural haematomas. Pinnae alopecia, crusts and excoriations are common, and a discharge is often present (Hnilica, 2010).

The basic diagnosis work-up for suspected otitis externa should include physical examination, otoscopic examination and ear cytology.

Treatment will depend on the cytologic findings. Ear cleaners and medicated topical products are used according to the infectious agents identified. Severe infection may require ear flushing under general anaesthesia.

Ear cytology

Why?

Cytology of the otic exudate is a simple, quick and inexpensive test, and should ideally be performed in every single case presenting with clinical signs of otitis externa. First, it enables the clinician to confirm or rule out the presence of an infection. In the landscape of growing concerns over the development of antibiotic resistance, antibiotics, even in topical form, should only be used when an infection is confirmed or highly suspected, and not for empirical treatment of non-specific signs. Cytology offers the veterinary team a quick and cost-effective way to confirm or rule out the presence of infection in the ear canal. Second, cytology also allows the clinician to characterise the infective agent (yeast versus bacterial, rods versus coccoid bacteria), therefore guiding the choice of treatment. Again due to the rising concerns over bacterial resistance, the use of multi-compound preparations should no longer be gold standard, and veterinary medicine needs to evolve to favour more specific therapy. For example, there is little point using an antibiotic preparation if the problem is caused by a severe yeast infection. Similarly, different antibiotics should be used in case of a predominantly coccoid infection compared with when rods are present.

In addition, because of the high incidence of antimicrobial resistance associated with Pseudomonas spp, the presence of rods is an indication for culture and sensitivity testing to be performed (Graham-Mize and Rosser, 2004). Cytology is the only way to confirm whether rods are involved in the presenting clinical signs, and therefore make a decision regarding the need for culture.

Finally, ear cytology is also a useful tool to monitor the response to treatment, particularly in chronic infections requiring long-term treatment.

How?

Collecting and staining samples

Taking a sample for ear cytology is a very quick and easy procedure. The only equipment required is ear cotton buds and microscope slides. Samples should be collected before any cleaning agent or ear medication is instilled in the ear, and preferably from the deeper horizontal ear canal, rather than the more superficial vertical canal. The cotton bud is inserted into the ear canal, rotated several times to collect material and withdrawn (Figure 1). The cotton bud is then rolled gently (not smeared) onto a clean, dry microscope slide in a thin layer (Figure 2) (Valenciano and Cowell, 2013). Samples should be collected from both ears, as patients that seem to have unilateral otitis may sometime have milder, less apparent disease in the contralateral ear, and also because even when both ears are affected, it is not uncommon to have a different pathology in each ear. The slides must be labelled accordingly, indicating which ear was sampled.

Heat fixation is not necessary (Griffin et al, 2007), and the samples can now be stained directly. The most commonly used stains for this purpose are the modified Wright's stain (Diff-Quick), which consist of three dips: an alcohol fixative and two solutions. The slide is dipped five times for 1 second into each dip starting with the alcohol fixative (transparent), then the red solution and finally the purple solution (Figure 3). It is advised to let the excess solution drain between each jar to avoid contamination, but the slide should not be allowed to dry between each dip. Finally, the slide is rinsed under tap water, and gently dried with towel paper, blow-dried or allowed to stand and air dry, depending on personal preference.

Interpreting samples

Normal ear canal cytology is characterised by cerumen (ear-wax), exfoliated squamous epithelial cells from the ear canal, a low number of commensal organisms, and potentially a number of different environmental contaminants. Smears should be evaluated for different types and relative numbers of bacteria (rods, cocci), yeasts (Malassezia), and inflammatory cells (neutrophils).

Common findings on ear cytology

Cerumen

Cerumen has high lipid content and therefore does not take up stain. It appears as non-stained background and debris on many normal ear cytologies.

Keratinocytes

Those are large, flat, lightly stained, usually non-nucleated, hexagonal shape structures (Figure 4). They may also be seen in a rolled-up fashion, and will then appear as cigar-shaped darkly stained structures. Occasional nucleated squamous cells may also be noted, and this does not necessarily mean that a pathologic process is involved; however nucleated cells tend to be more common in inflammatory conditions, as cells will be exfoliated more readily.

Yeast

Yeast, most commonly Malassezia pachydermatis, have a very characteristic ‘snowman’ or ‘footprint’ shape (Figure 4), and uptake the stain very well, giving them a dark purple colour. These are commensal organisms in the ear canal, and may be seen in very low numbers in clinically normal ears. Only few quantitative studies have been conducted to try and characterise the number of normal versus overgrowth of Malassezia, and there is no consensus at the moment amongst dermatologists as to how many Malassezia can be considered normal flora vs overgrowth.

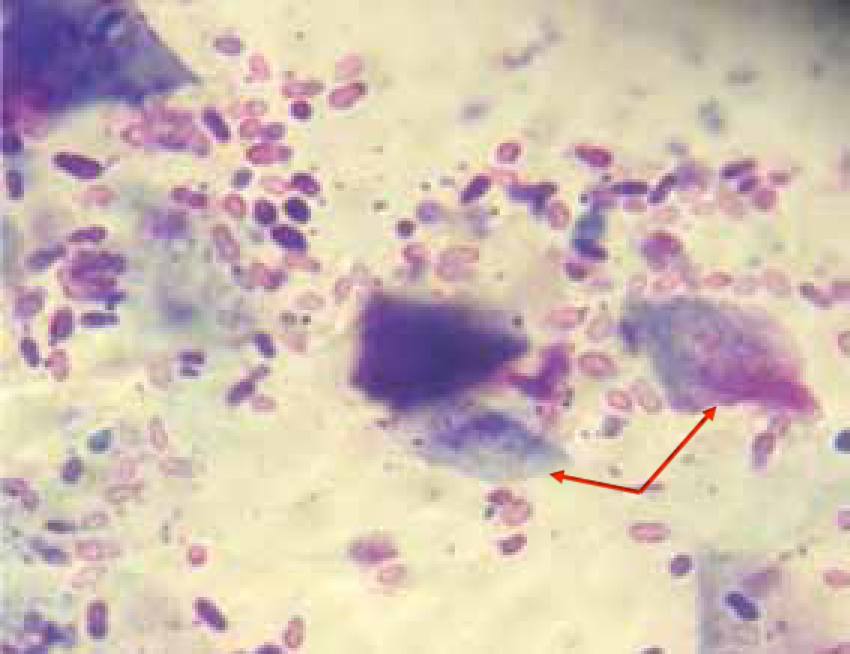

Bacteria

Bacteria are also commonly identified on ear cytology. With a little practice, it is possible to distinguish between rods and cocci (Figure 5), which is very important for treatment selection. Coccoid bacteria are likely to belong to the Staphylococcus or Streptococcus genus, while rods are usually Pseudomonas spp or Proteus spp (Angus, 2004). As mentioned before, the presence of rods on ear cytology is an indication for bacterial culture and sensitivity to be performed.

Similarly to Malassezia, Staphylococci are commensals of the skin and ear canal, and the ear canal of healthy dogs contains a small number of bacteria. However, bacterial concentration is typically low enough so that only occasional or no bacteria may be seen on cytology.

Environmental contaminants

A wide range of other structures may appear on ear cytology slides, resulting from environmental contamination, such as pollens, fungal structures, fibres, and so forth. These are of no clinical relevance.

Conclusion

As discussed, ear cytology should ideally been performed in every case presenting signs of otitis externa, in order to decrease the use of antibiotics and better target specific infections. It is a simple and quick procedure which can yield a lot of very useful information when treating ear disease. Unfortunately, ear cytology is still too often overlooked in practice, and the veterinary nurse certainly has a role to play in promoting its use within the practice.