As veterinary practices work around the clock to provide care, shift changeovers with an increased number of personnel involved in patient care are an inevitable part of practice life. As such, an effective patient handover procedure is vital, as this enables staff to accurately transfer information, responsibility, and accountability for some or all aspects of care for a patient, or groups of patients, to another person or professional group on a temporary or permanent basis (BMA et al, 2004; WHO, 2007; Burton, 2018). The primary goal of patient handover is to provide accurate transfer of information necessary for continuing safe patient care (Manser et al, 2012).

Benefits of effective patient handover

Benefits to patients/clients

- Safety is protected: lapses in information handover can, and do, lead to mistakes being made which increases morbidity and mortality.

- Less discontinuity of care: poor handover can lead to fragmentation and inconsistency of care.

- Individualised patient care: essential information pertaining to the individual patient is disseminated, for example, feeding preferences.

- Decreased repetition: clients dislike having to answer the same questions. Clients are more readily accepting of different people providing their pet with care as long as the existing knowledge is retained.

- Increased service satisfaction: client perception of professionalism is reaffirmed and improved.

Benefits to staff

- Education: effective handover will be of daily benefit to practice and assists the development of broadening communication skills. A well-led handover session provides a useful exercise for students to observe and learn from.

- Professional protection: clear and accountable communication can protect staff against blame should errors occur.

- Reduction of stress: having the full picture and feeling informed allows staff to feel less unsupported and more in control of a patient's care.

- Job satisfaction; effective patient handover increases patient care. The provision of high quality care is fundamental to veterinary personnel's job satisfaction (BMA et al, 2004).

In a relay race, how the baton is passed between runners is pivotal to success or failure, and Davey and Cole (2015) proposed it was a useful analogy to describe patient handover, suggesting that missed or misunderstood information can have a direct and even dangerous impact on the care of a patient (see Figure 1). Davey and Cole (2015) advocated the use of a standardised approach to handover to ensure the ‘baton’ is passed successfully and the right information is given to the right people at the right time, in the right way…..every time!

Moving to a standardised approach — where to start?

Start by finding out any existing policies or protocols for transfer of care within your organisation. At this point, you may be unsure exactly what part of the handover process you want to improve, or even how wide your focus will be — team, department, organisation? The first step is to get a clear idea of what is happening with current handover processes and start to understand where the problems and solutions might be found. Davey and Cole (2015) suggested observing a patient handover within the organisation and recording the findings, further stressing that staff must not feel as though they are being tested. As handover of patients can vary, depending on the time of day and who is doing it, observing several handovers is advocated.

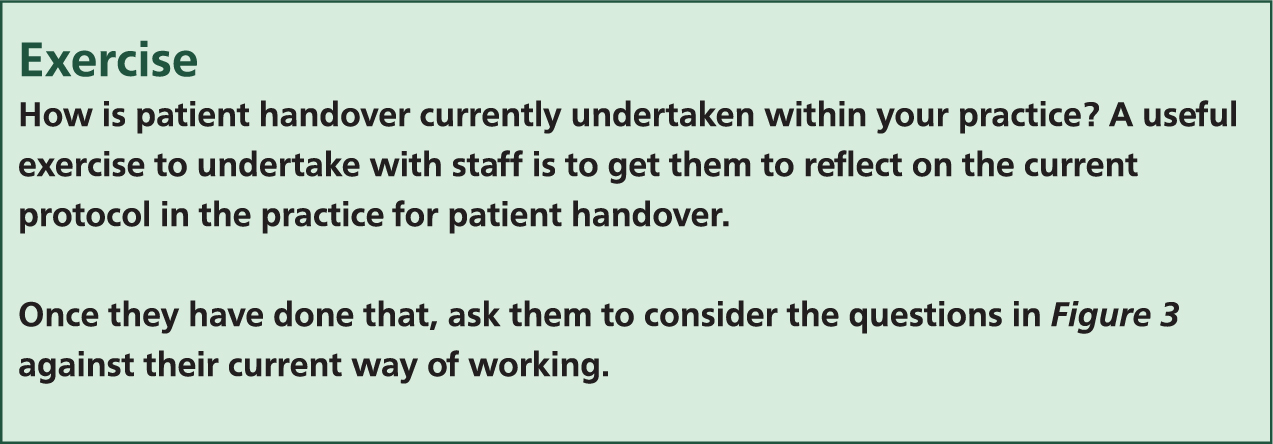

It can also be useful to get the team to self-assess their current way of working using the exercise shown in Figure 2.

Do the principles align? If not, this exercise may prove a useful starting point for the creation of a standardised approach to patient handover. Developing a handover policy will require a coordinated approach from managers as well as all members of the multidisciplinary team. Management input is required as organisational change may well be required to enable effective handover to occur (BMA et al, 2004).

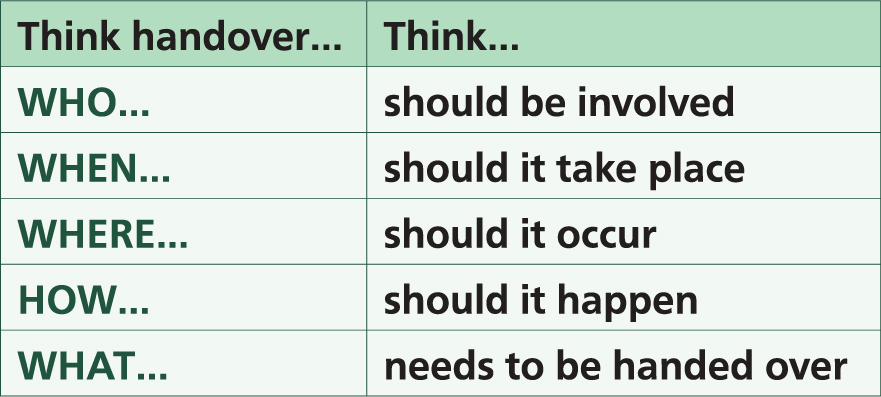

It is beyond the scope of this article to describe a model of patient handover that will suit all veterinary practices. Therefore, the factors listed in Figure 3 will be discussed in a little more detail in order that personnel may use them as the basis of development of their own standardised way of working.

Who

- Each practice needs to identify the key people who need to attend handover. The ideal model as suggested by BMA et at (2004) includes all grades of staff from each included speciality or ward as appropriate. The senior nursing cover for the period should be present.

- A handover leader should be identified; this is likely to be the senior veterinary surgeon or nurse involved in the case.

- The handover leader should ensure the team are aware of any new or locum staff members of the team and ensure adequate arrangements are in place to familiarise them with the practice geography and systems of working.

When and where

- Carry out patient handovers at the same time for each changing shift and ensure there is sufficient time to cover everything required. The time required for handover naturally depends on the complexity of the case, however Burton (2018) suggested that generally this will not take longer than 30 minutes.

- The handover should take place during working hours, for both the person giving and receiving the handover. If shifts are not coordinated accordingly, staff may end up staying late or arriving early to ensure handover occurs. In worst case scenarios, handover may not occur if staff are unable or unwilling to stay.

- Patient handover may need to occur several times a day depending on the shift patterns of the practice; this is especially prevalent in large hospital practices.

- Unless in the case of an emergency, handover should be carried out in a location where staff will not be disturbed. There will always be work which is on-going during the handover period, especially in the evening. BMA et al (2005) however suggested that virtually all aspects of care can wait for 30 minutes to ensure continued safety for patients. Individuals need to be allowed to attend, subject to emergency cover being defined.

- The handover location should have access to laboratory results, radiographs, clinical information, the internet/intranet and a telephone

- When undertaking handover for a single patient, this can be hosted at their kennel/cage in order that the patient can be observed during the discussion.

How

- The style of handover will of course be dependent on the style of veterinary practice — this may include whole hospital handovers to night teams, local handovers on specific units or multiple sites for those practices that transfer patients out-of-hours. Irrespective of the style of practice, all handovers need a predetermined format and structure to ensure adequate information exchange. Ad hoc handovers often miss out important aspects of care (BMA et al, 2004).

- Information should be communicated in a simple, clear style, avoiding jargon and unnecessary narrative and only using standard abbreviations that are common to all.

- The designated handover lead must take ownership of the process and should not permit other people to have conversations amongst themselves while they are speaking. Burton (2018) advised preventing staff from continuously interrupting with questions during the handover, further suggesting that staff should be encouraged to save their questions until the leader has finished discussing that patient.

What

- The identity of the patient(s).

- The location of the patient(s).

- Their current condition/status and whether it is stable or not.

- Any adverse reactions/complications which have occurred.

- Actions that have recently been taken.

- Their current and anticipated needs, to clarify management plans and ensure appropriate review.

- Any medication they are on or need.

- Recommendations of what action the staff need to take.

- The timeframe within which certain tasks need completing.

- Any outstanding tasks, including their required time for completion.

- Relevant background and or client information (BMA et al, 2004; Eggins and Slade, 2015; Burton, 2018).

It is essential to strike a balance between comprehensive and excessive. Staff must know how to organise all the essential information concisely, so other staff can easily grasp and remember it without becoming overwhelmed (Burton, 2018). A standardised approach to patient handover will help to ensure this is the case.

A good practice checklist (Figure 4) can be a useful tool when devising a new approach to patient handover. Before each handover, the questions in Figure 4 should be asked.

Structured communication tools

There are a number of different structured communication tools utilised within healthcare settings designed as easy-to-remember mechanisms that can be used to frame conversations. Such tools enable personnel to clarify what information should be communicated between team members, and how (Davey and Cole, 2015).

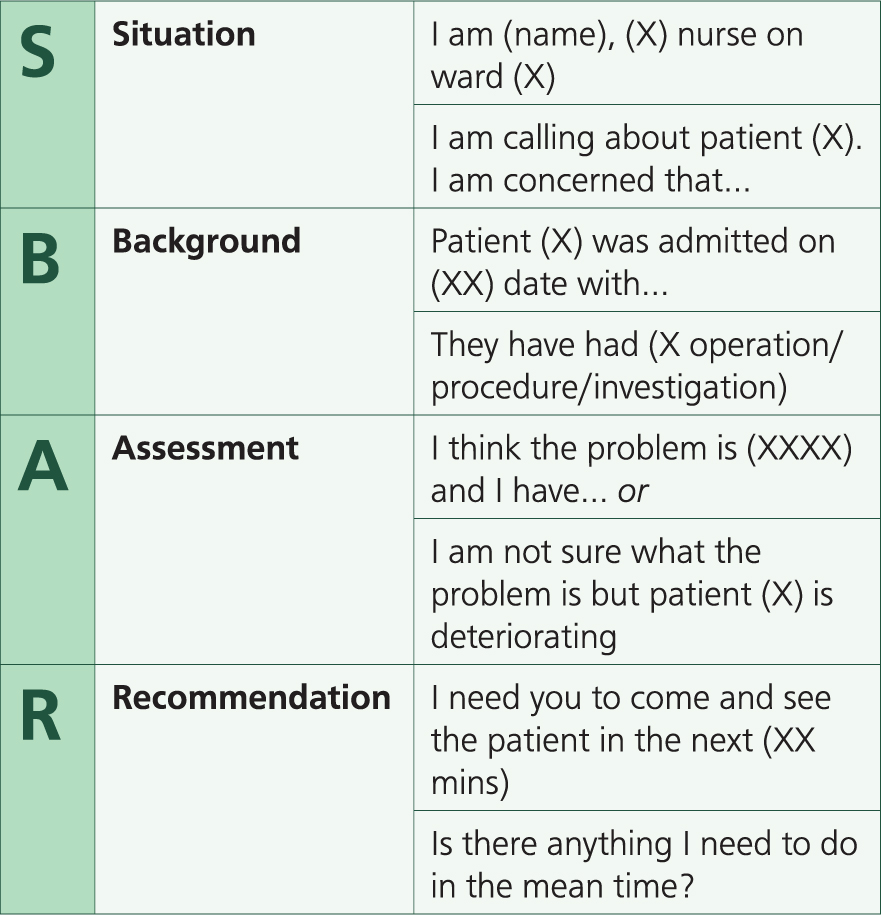

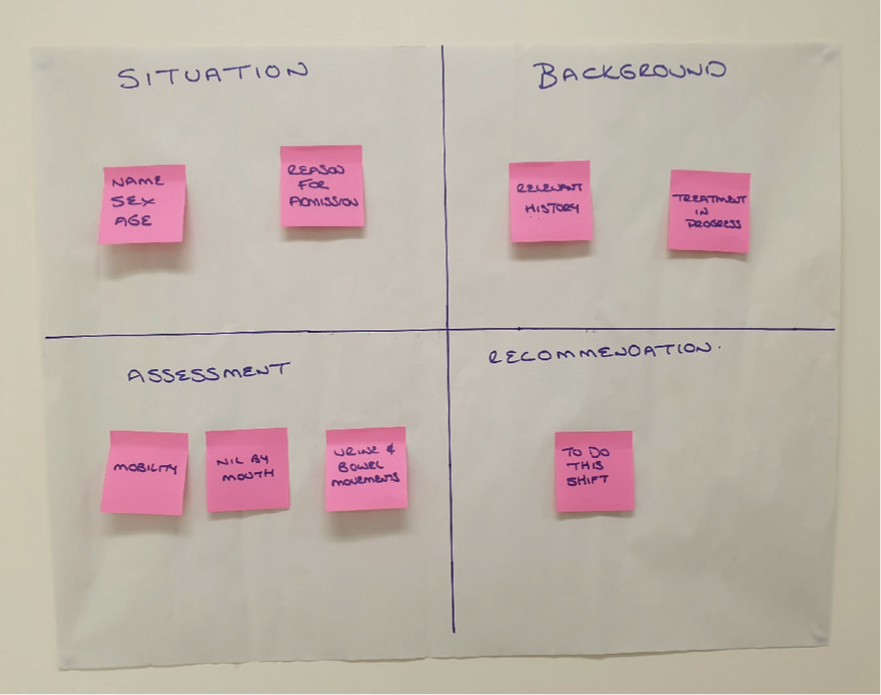

SBAR is an example of a structured communication tool which stands for situation, background, assessment and recommendation. Many healthcare settings utilise this structure for patient handover as it permits staff to record information in a memorable and focused format, with an appropriate level of detail (Davey and Cole, 2015; ACT Academy, 2018; Burton 2018).

SBAR consists of standardised prompt questions in four sections to ensure staff are sharing concise and focused information. It helps staff to communicate assertively and effectively and reduces the need for repetition and thus the likelihood for errors. It can prove especially useful in reducing the barrier to effective communication across different disciplines and between different levels of staff (ACT Academy 2018). An example of the SBAR communication tool is shown in Figure 5.

Although a simple and effective tool, ACT Academy (2018) suggested incorporating SBAR can take considerable effort and require significant training. It is therefore the intention of this article to merely introduce readers to the SBAR concept. Interested parties can gain more information from: https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/2162/sbar-communication-tool.pdf

Healthcare settings utilising the SBAR model have found that notepads or paper with the tool printed on them (Figure 6), pocket cards and stickers on telephones are useful aides in the early implementation of the tool within an organisation (Davey and Cole, 2015; ACT Academy, 2018).

Conclusion

Evidence would suggest that the underlying mechanisms of team performance in a complex cognitive task can be better understood if one considers associated team processes, such as communication and coordination. Without this knowledge, Manser et al (2012) suggested standardisation efforts may be premature.

During patient handover, it is essential to speak up if you are unsure; it sounds obvious but never be tempted to make up what you think is happening! If you do not know the answer to a question you are asked about a patient's care, say you do not know or better yet check their chart. Next time you will be better prepared by checking before-hand (Entwistle, 2011). Following a standardised approach to handover should help ensure there are no delays or mis-communications that put patients' safety at risk. Burton (2018) suggested this will enable staff in the next shift to address the immediate needs of patients and maintain a consistent, coordinated level of care.

KEY POINTS

- Shift changeovers and hence an increasing number of personnel involved in patient care are an inevitable part of practice life.

- The primary goal of patient handover is the accurate transfer of information necessary for continuing safe patient care.

- It is essential to strike a balance between comprehensive and excessive during patient handover.

- A standardised approach to patient handover is advocated.

- Structured communication tools enable personnel to clarify what information should be communicated between team members, and how.