Open wounds require exudate for moist wound healing. However, in practice when wounds produce insufficient or over produce exudate, this can be detrimental to the healing environment. There are many complications that can delay healing processes, cause distress to veterinary patients, and can have costly implications to clients. By managing exudate and using appropriate dressings, the effectiveness of nursing can be increased and this can help to accelerate the healing process to provide a positive outcome for patients. It is an essential skill for veterinary nurses to be able to provide the correct equipment and environment for wound assessment, cleaning and ongoing management of the wounds presented in veterinary practice.

What is exudate?

Exudate is generally defined as fluid that is being expelled from a wound through capillaries (Barrett, 2016). It plays an essential role in the wound healing process and is composed mainly of water. It can also contain electrolytes, nutrients, proteins, inflammatory mediators, protein digesting enzymes, growth factors and waste products (Dowsett, 2011). The fluid can contain a variety of cells such as neutrophils, macrophages and platelets. Wound exudate will also frequently contain different microorganisms, however this does not necessarily mean that the wound is infected. The appearance of exudate from a wound is normally clear, or pale yellow and of a watery consistency. It normally has no odour, although dressings and dressing adjunctive may produce an odour (Kerr, 2014). If a wound is necrotic or is undergoing an enzymatic debridement, the exudate produced may be of an opaque or light brown colour, and occasionally grey or green if bacteria are present. This may be in conjunction with a foul odour (Dowsett, 2011).

What does exudate do?

The role of exudate in a healing wound is to support the healing process and control a moist wound environment (Beldon, 2016). The substance allows diffusion of the vital healing factors (growth and immune) and the migration of cells across the wound bed (Barrett, 2016). It promotes cell proliferation, provides nutrients for cell metabolism and will aid autolysis of any necrotic or damaged tissue (Dowsett, 2011). The amount of exudate will reduce when healing occurs. Monitoring the amount of exudate therefore is very important, especially in relation to skin surface area (Barrett, 2016). Large wounds, such as burns and ulcers, which can be the most highly exudative wounds seen, will lose excessive amount of fluid so care of patients regarding hydration levels is vital. Despite requiring a moist environment for wound healing, over production of exudate can hinder the healing process (Barrett 2016). This may occur when there is capillary leakage or bacterial contamination which can dramatically increase exudate production, and this produces a need to rebalance the wound environment by evaluating the wound and the patient's health status. In chronic non-healing wounds exudate can impede healing (Beldon, 2016). It can slow down or prevent cell proliferation affecting growth factor availability, as it contains raised levels of inflammatory mediators (Kerr, 2014). This increased proteolytic activity of chronic wound exudate can damage the wound bed by degrading the extracellular matrix (Dowsett, 2011).

Any changes to exudate from a wound, e.g. colour, odour or consistency, may be extremely significant as this could indicate a change in the wound's status or be a sign of a concurrent disease process. This should prompt the registered veterinary nurse (RVN) and nursing assistants, who can often see subtle changes in a patient's wound, demeanour and clinical status, to alert the veterinary surgeon to re-evaluate the patient's health status (Young, 2013). This patient evaluation can therefore aid wound healing if exudate is managed effectively (Beldon, 2016) and early observations can reduce wound healing times, indicate any surrounding skin damage, signs of infection, a reduction in dressing change frequency. If there is a requirement for any anaesthesia or sedations this should be documented along with any changes in the analgesia regimen (Barrett, 2016).

Managing exudate

Dressings are the main option to manage exudate, and they will either maintain or reduce wound moisture. There are many dressings available which either absorb exudate or donate fluid to create a moist wound environment (Barrett, 2016). Dressings consist of a wound contact layer, an absorbent layer and a non-permeable or semi-permeable layer, or a semi permeable backing. Exudate-related changes to a wound, such as maceration, can be reduced by minimising the skin contact with exudate by applying an appropriate dressing which can act as a skin barrier (Cutting and Westgate, 2012). Table 1 summarises dressings used in exudative wounds and this article will look at some of these in more detail. Before any management of exudate, the wound and surrounding skin should be clipped carefully and cleaned in an aseptic manner as per the step by step guide (Box 1). Before cleaning of the wound, it may be necessary to take a culture and sensitivity swab, especially if it is a chronic non-healing wound, to assess any bacteria that may be present (Kirk, 2013). This will enable the veterinary surgeon to select the correct antibiotic dependent on sensitivity from the culture. Wearing gloves, any skin deficits should be filled with sterile water-based jelly (O'Dwyer, 2012), and then an extensive area clipped with sharp clean, preferably sterile clipper blades (Bowers, 2012). Cleaning the gross debris with sterile swabs and then extensively flushing the wound can be crucial in initial wound management. Solutions for cleaning wounds include tap water (to removed gross contamination immediately), sterile lactated ringers (Kirk, 2013), povidone iodine solution or irrigating solutions such as Prontosan® (B. Braun) (Andriessen and Eberlein, 2008). The author has found using a sterile kidney dish to collect excess fluid to be advantageous and prevent recontamination. All stages should be performed aseptically. Patients will often tolerate this conscious with adequate analgesia to avoid sedation or anaesthesia, especially following trauma or when in shock where chemical restraint should be avoided (O'Dwyer, 2012). Once the area has been cleaned and assessed dressings are the next stage of management of the wound, either temporarily until surgical intervention or for ongoing medical wound management.

| Dressing type | Product | Manufacturer | Exudate absoption Level | Clinical Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry | Melonin◊ | Smith & Nephew | Low | Simple dressings, typically used post surgery |

| Zorbopad | Millpledge | Low | Simple dressings, typically used post surgery | |

| Primapore | Smith & Nephew | Low | Simple dressing with adehesive border and non adherent absorbent pad, used post surgery | |

| Leukomed® | BSN Medical | Low | Simple dressing with adehesive border and non adherent absorbent pad, used post surgery | |

| Leukomed Sorbact® | BSN Medical | Low to medium | As Leukomed but with a non-adherent bacterial binding absorbent pad | |

| Hydrocolloid | DUOderm® | ConvaTec | Medium | Sheet which can aid debridement, can maintain and donate fluid but also absorb exudate |

| Foam dressings | Allevyn◊ | Smith & Nephew | Low to medium | Non-adherent contact layer with hydrophillic middle and semipermeable film backing |

| Advasorb® | Advancis Veterinary | Low to medium | Two layer non-adherent foam, hydrophillic contact layer and semi-permeable film backing | |

| Cutimed Siltec® | BSN Medical | Low, medium, high | Foam and silicone contact layer for fragile wounds. |

|

| Hydrofibre | Aquacel® | ConvaTec | High | Hydrophobic polymer which removes fluid and locks away into the dressing away from wound bed. Available with silver (Aquacel Ag) |

| Alginate | Durafibre® | Smith & Nephew | High | Available also with silver, and in different forms such as ropes and sheets. Will lock exudate absorbed away from wound, but maintain its conformity to the wound bed |

Simple dressings

Simple dressings are not able to retain any liquid under pressure such as Primapore◊ (Smith & Nephew) or Melonin◊ (Smith & Nephew) so these are not recommended in highly exudative wounds (Chivers, 2010). Leukomed Sorbact® (BSN Medical) is the exception to this as, although it is only a dressing covering, it has a bacterial binding layer to help prevent colonisation of bacteria and fungi without a chemical agent. It will also hold exudate away from the skin to prevent maceration of a wound, but with reliable adhesion to the surrounding skin to ensure it is secure and will stay in place, even in difficult areas. Figure 1a shows a Leukomed Sorbact® dressing before application. The green dressing is the absorbent bacterial binding layer. Figure 1b shows the dressing in place on the stifle, a highly mobile area. These dressings are more reliable at staying in place than other simple dressings. Figure 1c shows the absorbency of the dressing in the bacterial binding layer. This infected stifle wound was heavily exudative and previous dressings required changing every few hours. By applying Leukomed Sorbact any bacteria would be bound to the contact layer and exudate absorbed away from the wound to prevent re-colonisation or maceration.

Although simple dressings are not advised in highly exudative wounds, tie over wound dressings, which are termed ‘simple’, can be invaluable. A tie-over dressing involves placing loose, simple interrupted sutures into the healthy skin bordering the wound with a large (0–2–0) monofilament suture normally 3–4 mm from the skin edge. Once the swabs are placed into the wound deficit, umbilical tape is laced through the loops of the sutures and tied to itself so the dressing will remain in place (Tobias and Tobias, 2014). These dressings absorb a large volume of fluid but also can be changed easily and often in the conscious patient, occasionally allowing the management of these wounds on an outpatient basis (Tobias and Tobias 2012). Figure 2 is a prime location for a highly exudative wound in a difficult area using the tie-over method with exploratory laparotomy swabs as an absorptive dressing. Figure 3 shows another difficult area to dress where absorption would be difficult to achieve with any other dressing on the top of the head. These dressings are very well tolerated but patients require hospitalisation.

Hydrocolloids

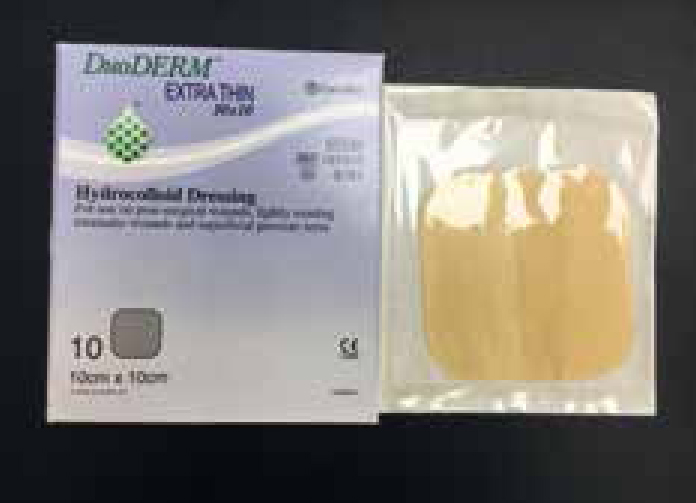

Hydrocolloid dressings are a suitable dressing for absorption of low to medium levels of exudate. They are constructed of polymers that can absorb fluids to form a moist gel at the wound bed, which also will produce an airtight bond with the skin (Chivers, 2010). They are made up of an external layer of polyurethane and an internal layer of gelatin, pectin, cellulose types, or other polysaccharides with hydrophilic properties. The hydrocolloid can provide or maintain moisture, and absorb excess exudate, promoting wound autolytic debridement and angiogenesis (Fletes-Vargas et al, 2016). An example of this dressing is DuoDERM®(ConvaTec) which is shown in Figure 4.

Foam dressings

Foam dressings, including Advazorb (Advancis Veterinary) or Allevyn◊ (Smith & Nephew) (Figure 5), can absorb moderate amount of exudate and have a breathable film to reduce maceration (Beldon, 2016). Foam dressings are generally made of semi-permeable polyurethane, although silicone foams have also been developed (Chivers, 2010). These dressings allow moisture to enter the wound maintaining a moist wound environment while keeping out and preventing spread of bacteria, and they can be used where infection is present (FletesVargas et al, 2016). Foams are also gas-permeable and provide thermal insulation. Foam dressings are superior to hydrocolloids for the treatment of exuding wounds and they are preferred for use on all wounds with varying levels of exudate. Foam dressings are available in various sizes and shapes with a range of thicknesses and in adhesive and non-adhesive presentation. They easily conform to difficult anatomical body areas as shown in Figure 6. This adhesive foam was applied pre skin stretching as this wound, from removal of a tumour, was highly exudative and had dehisced. To enable skin stretching to be effective so this wound could be closed, a highly absorptive dressing that would stay in place was required. Foams are indicated as primary dressing, but can be used on top of hydrogels and creams, for example when dressing necrotic, sloughing wounds or when a wound required moisture donation. They are also suitable for wounds with over granulation and during compression therapy (Fletes-Vargas et al, 2016).

Super absorbent dressings

High absorbing dressings or ‘super absorbent’ dressings, such as the Eclipse range (Advancis Veterinary) and Cutimed Sorbion Sachet® (BSN Medical) dressings (Figure 7), have a high absorbent capacity with a fluid repelling backing (Barrett, 2016). Alginate dressings are also highly absorbent and contain calcium or sodium alginate fibre derived from seaweed. They are dry when initially placed on an open wound, but on contact with wound exudate fluids they transform into a hydrophilic gel (Fletes-Vargas et al, 2016). Gels provide a reduction in lateral movement of fluid which helps reduce the chance of maceration and helps to protect surrounding tissue (Cutting and Westgate, 2012). The absorptive layer becomes larger as they draw in fluids, which prevents the wound from becoming dry by maintaining adequate moisture, and making dressing removal easier. Alginate dressings are able to absorb fluids up to 20 times their weight (Fletes-Vargas et al, 2016), and should only be used in moderate to heavily exuding wounds. The dressings also help to clean the wounds by activating autolytic debridement of any debris, protecting them from harmful bacteria, which helps lower the risk of infection (Chivers, 2010). Alginate dressings are also useful for wounds that are haemorrhaging as the calcium in these dressings' acts as a haemostatic agent and slows bleeding (Fletes-Vargas et al, 2016). Alginates are easy to use and they will mould themselves to the shape of the wound. They are made as flat dressings and rope dressings, and can be used for packing wound cavities. Durafiber◊ (Smith & Nephew) alginate dressings are designed for medium to heavily exudating wounds and will lock fluid and bacteria. They are often used as cavity dressings like the Allevyn Cavity◊ (Smith & Nephew) or Cutimed Cavity (BSN Medical) dressing. Figure 8a shows a fistula formation prior to placement of a cavity dressing and shows how highly exudative this area was. Figure 8b shows the placement of the dressing, and Figure 8c its use in conjunction with a tie-over method as discussed earlier. This dressing was used pre surgery to prevent further damage to surrounding tissues while surgery was planned.

Additionally hydrofibre dressings made of non-woven cellulose fibres have been synthetically formulated. The fibres are strongly hydrophilic and can rapidly absorb fluids and also hold the fluid within the dressing in a gel. The dressing will not lose its form so that it can continue to absorb exudate. These dressings can absorb up to 30 times their weight (FletesVargas et al, 2016). An example of a hydrofibre dressing is Aquacel® (ConvaTec) as shown in Figure 9.

Alternative methods of absorbing wound exudate

Management of exudate can also be highly effective with negative pressure wound therapy which has been around now for 16 years in the literature (Bell, 2016). It can be advantageous where exudate is unmanageable with more standardised dressings. There is evenly distributed negative pressure over the wound bed, and this allows removal of exudate, any infectious materials, and reduces oedema (Bell, 2016). Figure 10 show the dressing in place before negative pressure is applied and Figure 11 is with the unit working. A silver impregnated sponge covered with an occlusive sterile drape is place over the wound bed and surrounding tissues. The negative pressure wound therapy unit (Figure 12) is attached and draws fluid away from the wound at a pressure of −125 mmHg constantly. The canister attached to the unit absorbs exudate and the unit will alarm when the canister is full and requires changing. This is a sterile method of managing wound exudate, and is becoming more readily used in veterinary practice.

Wounds will require regular re-assessment which can vary between hours to days depending on the exudate levels and the type of dressings being used to ensure that the correct level of moisture is maintained. This will ensure dressing changes are done efficiently and appropriately. Therefore documenting and recording any changes is essential (Beldon, 2016) and if possible photographic evidence should be available on clinical notes. Excessive exudate can prolong wound healing so effective management of these cases is required by veterinary personnel.

Conclusion

Wounds can be challenging to manage especially when exudate levels are not at an optimum level for wound healing. Careful monitoring, re dressing and thorough documentation by the veterinary nurse can ensure that wounds of varying degrees of severity and stages of healing can heal at an optimum level and be resolved as quickly as possible. This also includes knowledge of wound healing advancements in both dressings and techniques which could be beneficial and aid the veterinary surgeon in determining a plan for a wound presented in veterinary practice.