Birds are becoming a more popular pet as the number of people living in small houses or flats increase. Parrots can be very interactive and fun pets, which do not always need to be kept in a large area. Because of this parrot ownership is on the rise and parrots are presenting to veterinary clinics more often. As urban areas increase in size more wildlife is being affected by human interaction, leading to more wild birds presenting to veterinary clinics (Savard et al, 2000). It is important to understand the nursing considerations required for avian patients to enable clinics to be prepared for when a bird inevitably presents.

Housing

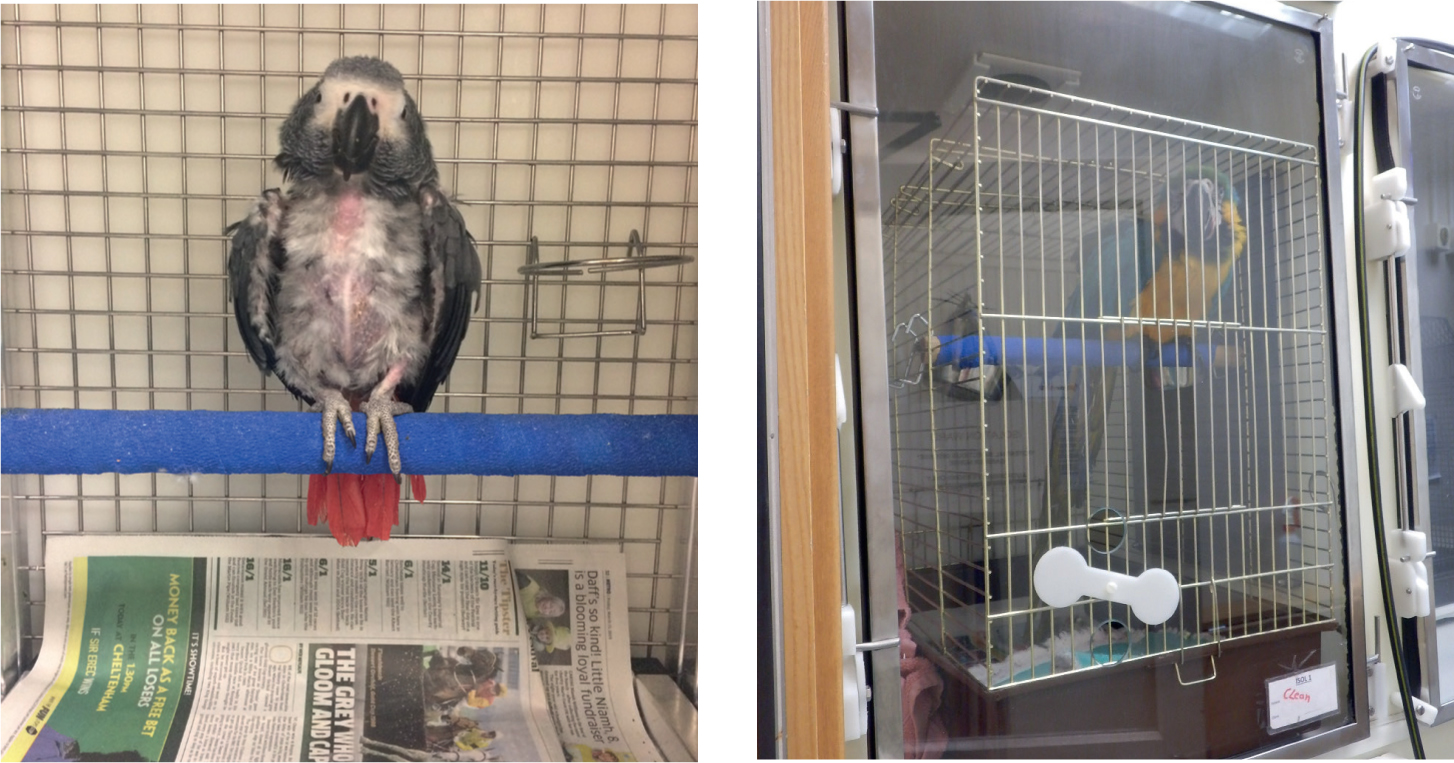

Parrots, waterfowl and birds of prey should be housed in different ways as they have different needs (Figures 1, 2 and 3). Parrots and birds of prey are arboreal species and they feel safer being housed as high as is safe and practical to do so. Waterfowl are more terrestrial species, which means that they should be housed on the ground. Parrots should be housed in a cage within a kennel as they like to climb about and move. Care should be taken to ensure that the cage is safe for the individual (suitable bar spacing and strength, a suitable size and made from suitable metals to include no zinc or lead involvement). Different sizes of parrot will require slightly different cages so there should be a variety available to cater for different species. The furniture in the cage should also be considered and, where required, some removed to aid the handling, catching and nursing of the patient during the stay. They should be able to climb from each end of the perch onto bars without having to juggle toys or furniture for their safety.

Birds of prey will require special raptor perches in a kennel. Falcons will prefer block perching whereas hawks prefer bow perching. This works alongside what they would normally be found perching on in the wild. It is important that with either perch, there is suitable padding to help prevent pressure sores which can lead to bumblefoot infections (ulcerative pododermatitis) — a bacterial infection and inflammatory reaction on the feet. An astroturf style substance or bandaging the perch with padding and protective bandaging materials are useful for protecting the feet in a hospital environment. It should be remembered that the perching material used should be able to be cleaned effectively between patients for good hygiene. It is important for birds of prey to be housed in a separate ward to parrots and waterfowl as they are predators to these species. If this is not possible then they should be housed out of sight of each other.

Waterfowl would naturally spend a lot of time on water or flying, and not a lot of time on the ground. Pressure sores and ulcerative pododermatitis can be found on the underside of feet where they have spent a long period of time on hard ground. However, it is understood that limitations within the veterinary sector may make housing them difficult. Padded bedding and the use of orthopaedic mattresses can be useful for bedding of waterfowl to reduce these risks. Waterfowl will feed by sifting through water with their whole beaks submerged. It is important therefore to provide a suitable container, such as a deep litter tray, for the food in water and a clean one for fresh water.

Diet/nutrition

There are different diet options for many different species, some are more ideal than others. It is important not to enforce a diet change when patients are not well. Birds of prey are fed whole prey diet, such as quail, rodents and day-old chicks. When birds of prey feed they will cast back up the fur/feathers and bones they have eaten. Therefore it is important to ensure that when they are on oral medications, the food is cast free (food without skin and large bones) to ensure that they do not have the medication in the cast they bring up.

Other birds may not eat in the hospital due to stress and being in unfamiliar environment. Getting owners to bring in normal diets can help encourage them to eat and also the presentation of the food in the normal form for the individual. This also helps provide knowledge as to what normal diet is offered and if changes should be made for a healthier, more nutritious option in the long term of the individual. If they are not eating in the hospital environment, supportive feeding should be offered which is commonly done via crop tube (as described later in the article). The right type of diet for the nutritional needs is important such as carnivorous for birds of prey and omnivorous diets for parrots and waterfowl. No more than 3% bodyweight should be fed in each feed to prevent overfeeding and risk of regurgitation (Scott, 2015).

Stress

Not all birds are a domesticated species that are used to human contact and interaction. It is therefore important to consider the range of different stimuli that could cause stress to an individual and what their individual stimulation thresholds are. Excessive handling or human interaction can cause stress, and it is important to ensure that everything is ready prior to handling the animal and that a clear plan is organised and discussed with the whole team before anything has begun. Sometimes the volume of traffic can also cause stress to individuals which are not used to it, such as waterfowl and birds of prey. Parrots are often more used to the handling and human contact and can prefer housing where they are able to see and hear humans. Alternatively, where possible, having the radio on or playing music can provide some background noise to alleviate the silence in a way they would experience at home (Simone-Freilicher et al, 2015). Knowing the background and routines of the individual can help understanding of what may be stressful to the patient.

Stress can also be as a result of the other animals in the wards in which they are housed. All birds should be housed away from cats and dogs as both of these can be predators to birds. It should also be considered that birds of prey are predators to small mammals and other birds, and therefore should not be housed alongside them. If there is a small mammal ward this could be used for the waterfowl and parrots, but otherwise isolation may provide a suitable option. Where neither of these are available, housing in a less frequently used room can be the best option, with a temporary kennel for their main house.

Similarly, to the birds being housed separate from predator and prey, it is also important that their carry boxes, if they are admitted, are also housed individually, and not do not develop predator/prey scents while the patient is hospitalised.

Providing environmental enrichment, such as making the bird work for their food, will give the bird something to do, which can help alleviate stress (Figure 4).

Zoonosis

Zoonotic diseases can be found in avian species and suitable precautions should always be taken. It can be possible to test for these, but the patient will most likely be hospitalised without the knowledge of disease status. These viruses and bacterial infections can be carried without causing clinical signs or illness and therefore appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) should be warn when handling all species, until their health status is known.

Avian influenza is a notifiable viral disease which has a risk of infecting humans. It can spread very quickly through flocks and is more common in, but not exclusive to, poultry and waterfowl. Good biosecurity should be followed throughout hospitalisation to reduce any spread or transmission of the disease. During high risk times, such as in the face of a disease outbreak, it may be recommended to ensure all at-risk individuals are kept outside of the building for assessment before entering the premises for treatment (Alexander, 2008).

Psittacosis is a common zoonosis found in parrots and similar families, and also in some wildlife such as pigeons. Good biosecurity, housing and hygiene should be provided for protection of both the current inpatients and also the staff. Psittacosis can also be carried by the individual birds without being actively shed and therefore any at-risk birds should be tested on admission and barrier nursed until they are known to be clear or under treatment and have stopped shedding (Lewis et al, 2012).

When dealing with zoonotic diseases it is important to ensure that staff are fully protected. This should include the use of gloves and gowns for uniform, hand and arm protection, masks for the prevention of feather dust inhalation (one of the methods of transmission of both diseases outlined above), and shoe covers for prevention of walking any bodily fluids or feather dust around the different clinical spaces. Each of these personal protective equipment (PPE) items should be new with each use and should be disposed of in a suitable isolation bin according to local waste disposal regulations (Dallas et al, 2003).

Handling

The most useful tool to use when catching any bird is a towel (Figures 5 and 6); lighter, smaller towels are useful for small psittacines and passerines, however with larger birds such as birds of prey and macaws a much larger, thicker towel protects the handler and allows the bird's entire body to be restrained. When picking up and restraining a bird it is important to hold the wings close to the body, as flapping increases the risk of feather damage or, in worst case scenarios, wing fractures. In parrots, the head needs to be adequately restrained as the beak poses a higher potential risk for injury to the handler, compared with the feet (Figure 7). The larger the parrot the more damage they can inflict with their beaks. In birds of prey the beak is less of a risk to the handler, however the head should still be restrained in these species as they can also bite as a defence mechanism. Birds of prey have large talons, which are the most likely cause of injury to the handler. The legs must be adequately restrained to avoid injury to the person administering treatment or examining the patient and also to the bird itself, as some birds will grip the opposite foot, resulting in penetration injuries (Figure 6). Towels can be utilised to restrain all parts of the body, with differences in techniques.

Birds breathe by active moving of the ribs, which expands the volume of the air sacs within the coelomic cavity. On inspiration the ribs and keel bone move in a craniolateral direction. This is essential for air flow and it is important that pressure is not placed on the sternum and keel bone to avoid restricting this movement. Handling is a delicate balance between holding the bird loosely to avoid restricting this movement and holding the patient firmly enough that it does not escape. When handling any bird, it is important that the keel and chest is allowed to move freely, which is often why handling of birds focuses on holding the head and cupping the body.

Parrots should be grasped from behind with a towel, in one hand for smaller parrots and with two hands for larger species. The wings should be tucked into the body and the head positioned between the thumb and the index finger. In larger parrots one hand is used to stabilise the head and the other used to hold the body. In general, larger parrots such as macaws can be held with, and tend to require, a much firmer grip around the head, compared with smaller parrots such as conures and budgies (Figure 8). Extra stabilisation can be achieved by holding the patient close to the body with care being taken not to place excessive force on the keel bone.

Birds of prey should also be grasped from behind using two hands (Figure 6), unless the patient is exceptionally small. The legs should be gripped between the thumb and index finger with the left hand holding the left leg and the right hand holding the right leg. Once the legs are secure, they can be held in one hand by transferring the leg opposite to the hand chosen to hold the patient's legs, to the space between the index and middle finger. The free hand can then be used to hold the patient's head (Figure 9). Corvids can also be caught up in the same manner. It is essential when handling falconry birds to ensure no feather damage is inflicted, as this may have significant impact on their flight ability.

Falconry birds of prey often present hooded, wearing equipment including anklets around the tibiotarsus with long strips of leather, called jesses, attached. A leash can be attached to the jesses via a swivel to allow the falconer to present the bird ‘on the fist’ where the bird sits on the falconer's gloved fist, with the leash restrained by the same hand. When held on a short leash the bird can be ‘cast’ (a word here which means to catch up) in a towel in the method described above. When birds of prey are held on the fist they gravitate towards the highest point, so it is important to hold the hand higher than the elbow, to prevent the bird attempting to move off the glove towards the handler's elbow. Hooded birds of prey are easier to cast as they cannot see the handler moving towards them, and falconry birds usually present hooded to keep them quiet and less distracted, especially in a new environment.

Waterfowl should be restrained by grasping from above and wrapping a towel around the body to ensure the wings do not flap. Larger birds, e.g. swans, can be held under the arm and the head can be restrained using the opposite hand by gripping behind the skull (Figure 10). Specialised swan bags can be used to immobilise and transport large water birds such as swans and geese (Figure 11).

In some instances, turning the lights off can aid in catching the patient, which can be useful if the patient is within a small cage with a small door. It is important to ensure that the handler maintains a firm grip on the patient, however not too tight as the patient will not be able to breathe. Birds do not have diaphragms, and so rely on air sacs to move air around the body. These expand when the chest expands, so if this movement is restricted then the patient is at risk of hypoxia and suffocation (King and McLelland, 1984). Once the patient is secure a physical examination can be performed and any medications required can be administered. Physical examination can be performed in a towel by removing limbs from restraint in a step-wise fashion.

Fluid administration

Fluids can be administered to birds intravenously or subcutaneously. Intravenous catheters can be placed in the basilic vein on the underside of the wing in parrots or birds of prey (Saunders and Whitlock, 2012). These often require suturing in place, as this is a high movement area and there is very little anatomy to tape the bung to. In waterfowl, the medial metatarsal vein is often used (Saunders and Whitlock, 2012). This is situated on the medial aspect of the metatarsus and can be raised by placing pressure just above the intertarsal joint, which is the avian equivalent of a hock joint. This can be taped in place around the leg and managed in a similar fashion to a peripheral intravenous catheter in dogs and cats. When not in use, wrapping a cohesive bandage over the bung can avoid soiling with faeces or dirt, due to the close proximity to the ground. A 24G or 26G cannula is often used. The use of lightweight bungs avoids excess weight and therefore drag on the intravenous catheter in such small patients.

Subcutaneous fluids are administered in the inguinal region or over the dorsal back (Saunders and Whitlock, 2012). It is essential when administering subcutaneous fluids that the syringe plunger is drawn back to ensure negative pressure is present before injecting. This is because birds have a number of air sacs which sit close to the skin surface, and if the needle is accidentally inserted into an air sac, fluid administration into the air sac can be fatal (Saunders and Whitlock, 2012). Subcutaneous fluids are administered using an appropriate sized needle for the patient. The inguinal area is identified by extending the chosen leg to its full range, then inserting the needle into the fold of skin created by this movement. Fluids administered over the dorsal back are done so over the scapulae, with a needle inserted at a 30° angle. In all cases it is important to visualise the needle inserting through the skin. This can be achieved by gently blowing on the feathers to part them. Wetting the feathers down with disinfectant or surgical spirit is also an option, but large amounts are discouraged as birds with wet feathers are prone to hypothermia. Intravenous fluids can be administered through a pre-placed intravenous catheter.

Intramuscular injections

Medications can be administered through an intravenous catheter (Figure 13), subcutaneously in the manner described above, orally or via intramuscular injection. Intramuscular injections are routinely administered in the pectoral muscles. These sit either side of the keel bone, just ventral to the crop and offer a large expanse of muscle into which medications can be injected. In patients lacking pectoral muscles, such as ratites, or ground-dwelling birds the femoral muscles can be used. Avoid injecting into the posterior aspect of the muscles as this can result in damage to the sciatic nerve (Saunders and Whitlock, 2012). Intramuscular injections should be administered with an appropriately sized needle at a 45° angle to the muscle. Draw the plunger back before injecting to ensure the needle is not in a blood vessel and then slowly inject. Care must be taken when injecting large volumes of fluids or alkaline drugs as these can be painful and lead to muscle necrosis. Volumes >2 ml/kg should be administered over multiple injection sites (Chitty, 2008).

Tube feeding

Gavage or tube feeding is an essential skill when caring for debilitated or anorexic birds. Specialised straight or curved metal crop tubes can be purchased, or spruells needles can be used. Soft tubing (drip tubing, large bore urinary catheters etc.) can be used in birds of prey, water birds or poultry, however should be avoided in parrots. This is due to the strong shearing forces of the beak, which can slice through soft plastic and result in a foreign body within the crop (Chitty, 2008). When administering nutrition via crop feeding the food should be warm but not hot enough to burn the crop (Saunders and Whitlock, 2012). Food can be tested by thermometer or placing a small amount on the inner wrist.

Birds lack an epiglottis and the glottis can be visualised at the base of the tongue. Any oral feeding or medications should be administered past the glottis to avoid aspiration (Chitty, 2008). The tube should be pre-measured to ensure it reaches the level of the crop, which sits just dorsal to the thoracic inlet. The crop is an enlargement of the distal oesophagus, used to store food before it passes through to the proventriculus. Some species, such as gulls and owls, lack a crop. A crop tube should be passed from the left lateral commissure of the beak towards the right side of the neck as the tube is advanced down the oesophagus to the level of the crop (Figures 14 and 15) (Chitty, 2005). The tube can be palpated in the crop as birds have complete tracheal rings and so two tube-like structures should be able to be palpated in the throat —the trachea and the crop tube. If only one tube can be palpated then the crop tube should be removed and repositioned. Administer medications and food slowly and assess for regurgitation as they are administered.

A number of commercially available products can be used for tube feeding, based on the patient's species. The authors use warmed EmerAid® routinely for hospitalised avian patients, with choice of product based on the dietary requirements of the patient being treated.

If medications and food are required concurrently it is important to administer the medications before the food in case the patient regurgitates and to make sure no medication remains behind in the crop tube. Medications can be pre-loaded into the crop tube if the volume is small, or if the volume of medication exceeds the volume of the crop tube the medication can be injected into the needle attachment opening of the feeding syringe to ensure if passes through first. If a number of treatments need to be administered, such as intramuscular injections, fluid administration etc. then crop tubing should be performed lasts due to the risk of regurgitation with prolonged handling with a full crop. Once performed the patient should be placed back into the hospitalisation cage and monitored for regurgitation.

Conclusion

Birds can make interactive and interesting patients, each species coming with their own nursing considerations. Appropriate administration of fluids, medications and feeding can vastly increase their chances of survival, especially in wildlife patients that can become stressed in a clinical setting when in close contact with humans.

KEY POINTS

- Avian patients require species-specific hospitalisation requirements as far away from the stress of noise in a busy veterinary practice as possible.

- Both captive and wild avian patients can carry zoonotic diseases which are important to be aware of due to the risk to human health.

- Handling of avian patients is species-specific, however the most useful tool for handling any species is an appropriately sized towel.

- Administration of fluids and medications can occur by a number of routes and in a number of sites over the body.

- Tube feeding is a very useful skill when dealing with very sick or debilitated avian patients.