Clinical audit, as defined by the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2002), is a quality improvement process that seeks to improve patient care and outcomes. Aspects of the structure, processes and outcomes of care are selected and systematically evaluated against explicit criteria. Where indicated, changes are implemented at an individual, team or service level and further monitoring is used to confirm improvement in healthcare delivery. Put more simply, the audit is an organised examination of ward and service practices which provides the opportunity to simultaneously review safety in the workplace and identify and remedy deficiencies (Bryce et al, 2007).

What clinical audit is not?

Clinical audit is not a ‘witch hunt’, it is not about apportioning blame, and it is not a negative activity. It does not involve large amounts of statistical analysis or technical expertise. It should be viewed as a constructive activity, with the aim of assessing, evaluating and ultimately improving clinical work, and not as a tool to be used for criticism of an individual.

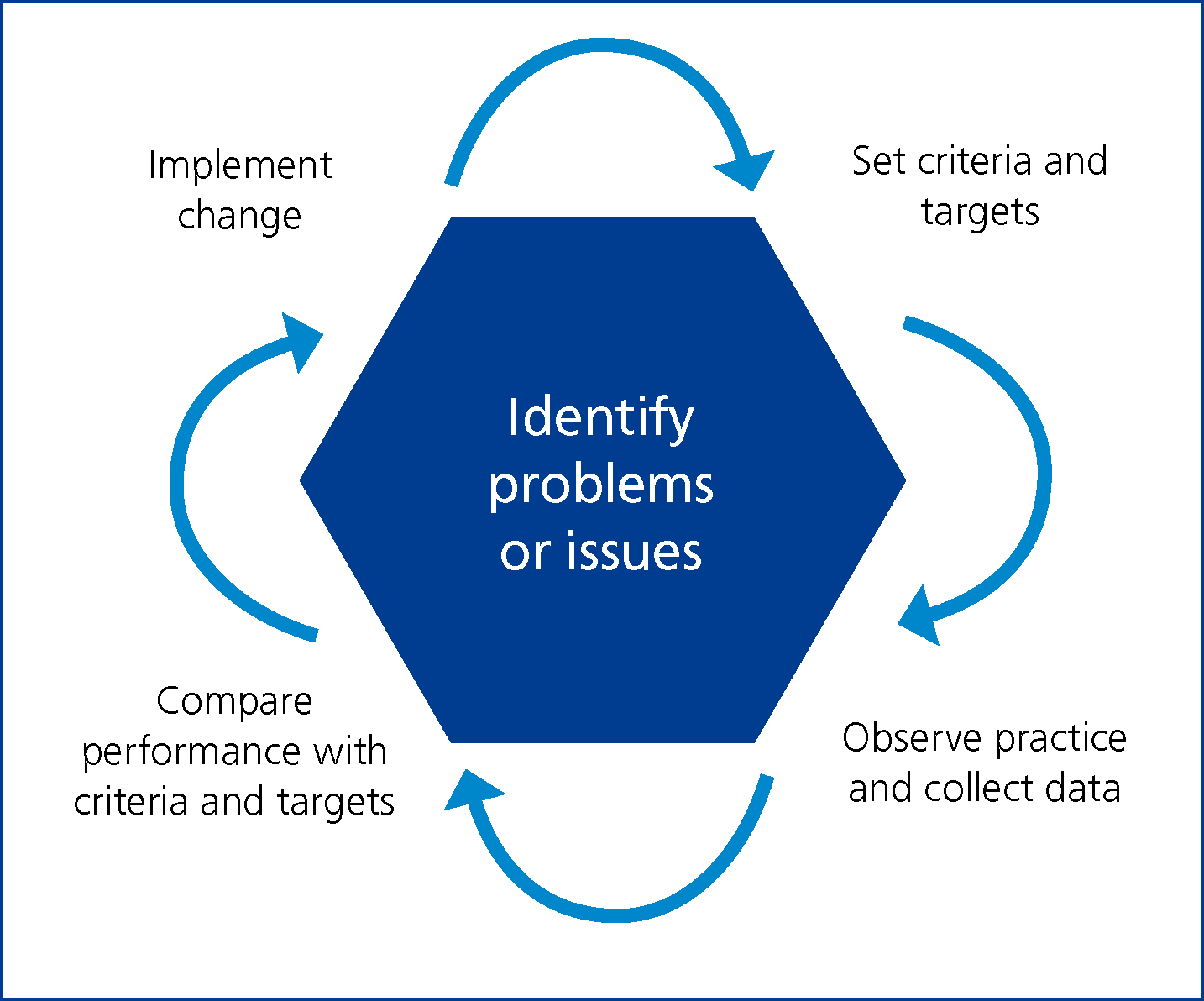

Central to the concept of audit is the audit cycle which traditionally comprises four basic stages as illustrated in Figure 1.

Once a topic has been selected for audit, the cycle includes specifying appropriate practice standards (see below), testing actual practice against these standards (data collection), analysing the data against the criteria and then deciding if and how changes need to be made.

Criteria and standards

Waine and Brennan (2015) compared clinical audit within the NHS to that of veterinary practice and found much disparity between the definition of criteria and standards. For the purposes of this article, a criterion can be defined as a systematically developed statement that can be used to assess the appropriateness of specific healthcare decisions, services and outcomes (Hay, 2006). For criteria to be valid, they must be explicit, evidence based, relate to important aspects of care and be measurable (NICE, 2002).

A standard refers to a required level of performance. The Royal College of Nursing (1990) defined a standard as an objective with guidance for its achievement given in the form of criteria sets which specify required resources and predicted outcomes.

Put simply, achievement of a standard requires compliance with criteria grouped together under the standard.

Setting of standards and criteria

Waine and Brennan (2015) identified the difficulties in setting standards and criteria for veterinary practice compared with the audit process within the NHS. Within the NHS the NICE guidelines are used as standards in many cases based on the best available evidence, such as systematic reviews and randomised control trials. As the equivalent evidence-based guidelines do not tend to exist in veterinary medicine, and there are fewer results of studies collected from first-opinion practice that could act as standards, Waine and Brennan (2015) stated that the development of evidence-based veterinary clinical guidelines was a challenging and detailed process. The development of such guidelines often involves the creation of the evidence initially, which they stated may be difficult for busy veterinary personnel to achieve and may also be somewhat arbitrary if little was known about the baseline level.

For those new to the audit process, as there appears to be disparity in the literature between the setting of standards and criteria, the author suggests a good place to start would be to decide on what you wish to audit and then as a team, work together utilising recognised sources of information such as the RCVS Practice Standards Scheme and peer-reviewed literature to set standards and associated criteria applicable to your individual settings.

As the development of good-quality guidelines, such as the RCVS Practice Standards Scheme, depends on careful review of the relevant research evidence, the setting of standards and criteria from such sources is likely to be valid.

Planning an audit

In order to be effective, audit projects require good planning from the outset and must have clear aims and objectives and a timescale in place. An essential part of this planning process involves establishing good communication links between all involved parties. Though a core group of people may take the lead on a project, it is essential that all those who may potentially be affected by the audit are kept informed of the way the project is progressing (Rayment, 2002).

Practice culture

In order to undertake meaningful audit and improve clinical practice, it is necessary to develop a culture of openness so that people feel free to report and discuss problems and ‘near misses’. In the past, the veterinary and medical professions have shied away from the discussion of problems. ‘Near miss’ reporting is now accepted practice in air traffic control, where problems are considered as a starting point for improving future performance (Viner, 2009).

Therefore, in order to make audit worthwhile and to improve clinical effectiveness within the practice, it is essential that all staff take an honest look at their performance and use problems as an opportunity to learn (Viner, 2009).

Audit and infection control

Hospital infection control is a good subject for audit as it affects patient care, quality of life and clinical outcomes (Hay, 2006). Audit programmes should include audits of infection control policies in wards and departments, microbiological safety and cleanliness audits of the hospital environment, and audits of standard healthcare equipment. An infection control audit presents an opportunity to promote infection prevention and control improvement activities in partnership with the whole practice team.

A comprehensive audit should include inspection of the physical environment, review of workplace infection control practices, and assessment of workers' knowledge and application of infection control principles.

Physical environment

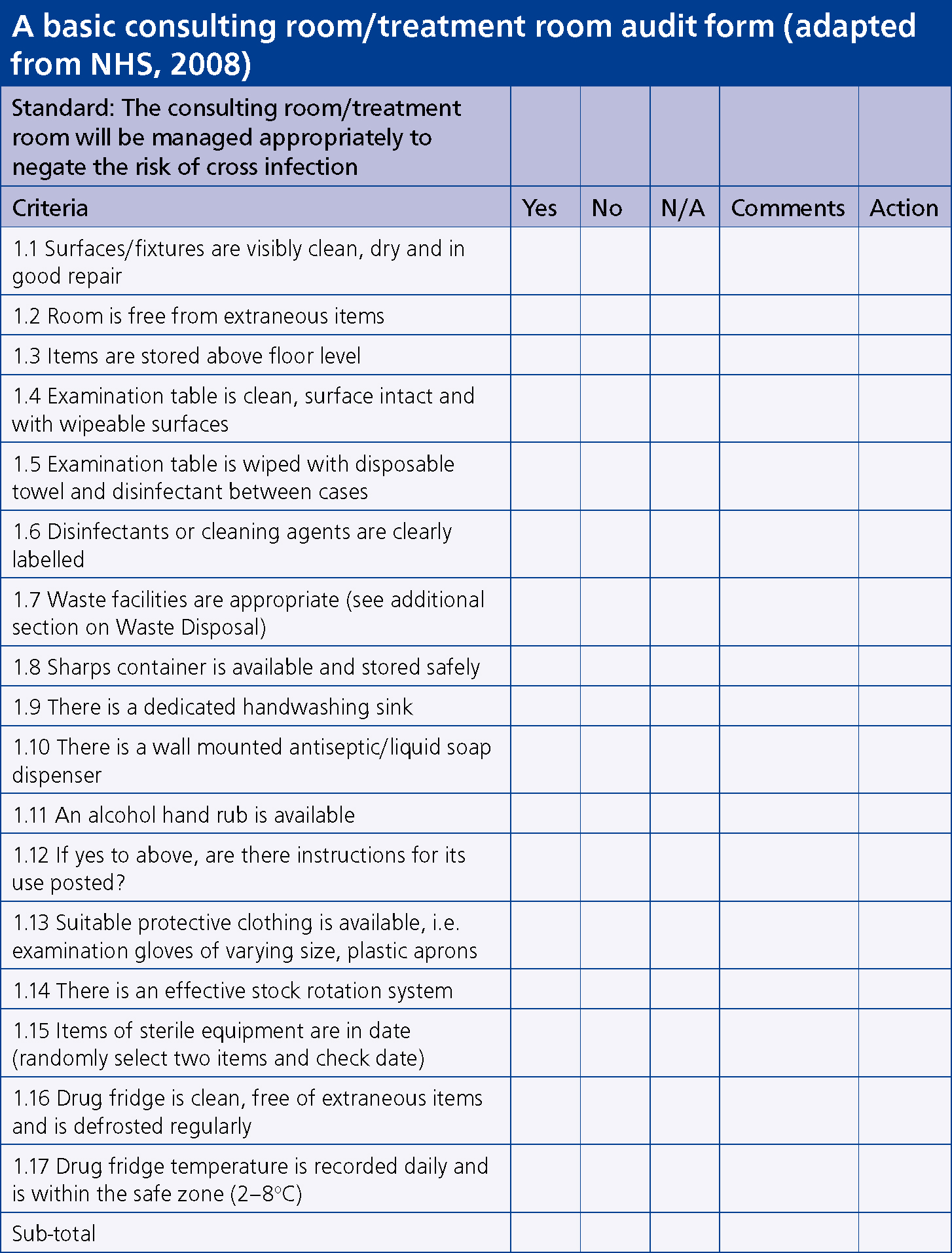

An assessment of the physical layout of any unit is necessary in order to determine the ease or difficulty with which staff can maintain a safe, clean environment and prevent cross infection (Figure 2). Good or poor design can affect one's ability to maintain a clean environment and clinical areas should be designed to facilitate good work habits (Hay, 2006). The process requires several visits to assess accurately the levels of cleanliness and consistency in cleaning practices.

Workplace practice review/staff knowledge

A major component of infection control is education of staff on routine precautions. Comprehension of infection control principles is paramount to the protection of both staff and patients. Emerging and re-emerging diseases, such as the influenza virus and antibiotic resistant bacteria, require that infection control policies and staff education sessions are regularly updated to take into account new information about transmission, prevention and control. Caveney et al (2012) stated that infection control procedures should include specific instructions for data collection of those agents relevant to the practice type, such as antimicrobial resistance, zoonotic disease, or nosocomial infections.

Prior to any documented observations in the work place, Hay (2006) suggested the use of an anonymous questionnaire to staff members in order to assess routine precautions, frequency of education sessions, staff member comprehension and application of infection control procedures. The purpose of the knowledge and staff questionnaire as part of the audit process is to ascertain the level of infection control knowledge, to determine whether perception of knowledge is genuine, and to evaluate whether knowledge is applied within the work place setting (Hay, 2006). It can also be utilised as a starting point to detect areas that will require immediate attention. It should be stressed to staff that confidentiality will be respected and that a standardised audit form will be used during the inspection and review process to ensure fairness and objectivity.

Once an area of practice to observe has been decided, hand hygiene for example, the infection control practice of all relevant staff is observed and evaluated using a standardised form to record lapses in accepted practice. Bryce et al (2007) suggested areas such as hand hygiene are observed and documented on at least three separate occasions and more frequently if deficiencies are initially noted. Personnel involved in conducting the observation must be clear as to what is expected; therefore a meeting should be set to ensure consistency of practice across auditors. Explicit instructions relating to hand hygiene might include:

Auditors should move around the practice as required to document events rather than targeting one specific area only. Please note that no more than three observations for an individual worker should be made. Only those situations where hand hygiene is unequivocally required should be documented:

Designing an audit document

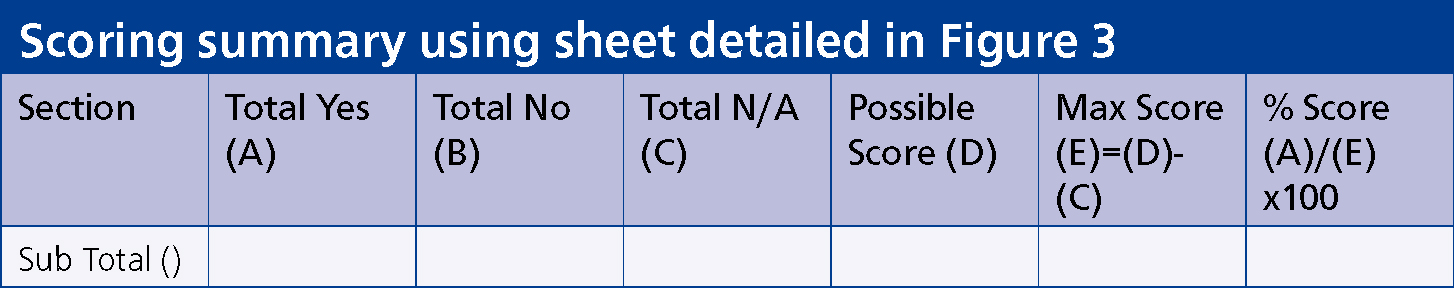

There are a number of approaches to designing an audit document and it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss them all in detail. The information contained in Figure 3 and 4 is for illustration purposes only and as previously stated, teams should work together utilising recognised sources such as RCVS Practice Standards Scheme and peer-reviewed literature to set standards and criteria applicable to their individual settings.

To complete the scoring for each section:

1 Point for every Yes

0 points for every No

This will give a total score for that section

Possible score = (Number of questions asked) (D)

Maximum score (E) = Possible score (D) – total Not Applicable score (C)

Percentage = Total Yes score ÷ Maximum score x 100

The timescales for frequency of audit must be determined during the audit design stage but an example might be:

It is recommended that if a score of 60% or less is obtained, an audit of the section is repeated in 3 months' time; if between 60–75% re-audit in 6 months; if greater than 75% reaudit in 1 year (NHS, 2008).

Evaluating the audit

A wide range of changes can be implemented on the basis of clinical audit results, including the development of clinical guidelines and pathways, the introduction of education sessions or training, and/or an expansion in the range of available information resources, for example leaflets or videos (Rayment, 2002).

Evaluation must take place at the end of the audit to ensure that the objectives were met and to identify what quality improvements have been implemented as a result of the exercise.

Evaluation is also a means of addressing and learning from any problems encountered along the way. If objectives were not met, then why not; was it due to lack of time, support or finances, or was the audit project a little too ambitious (Rayment, 2002).

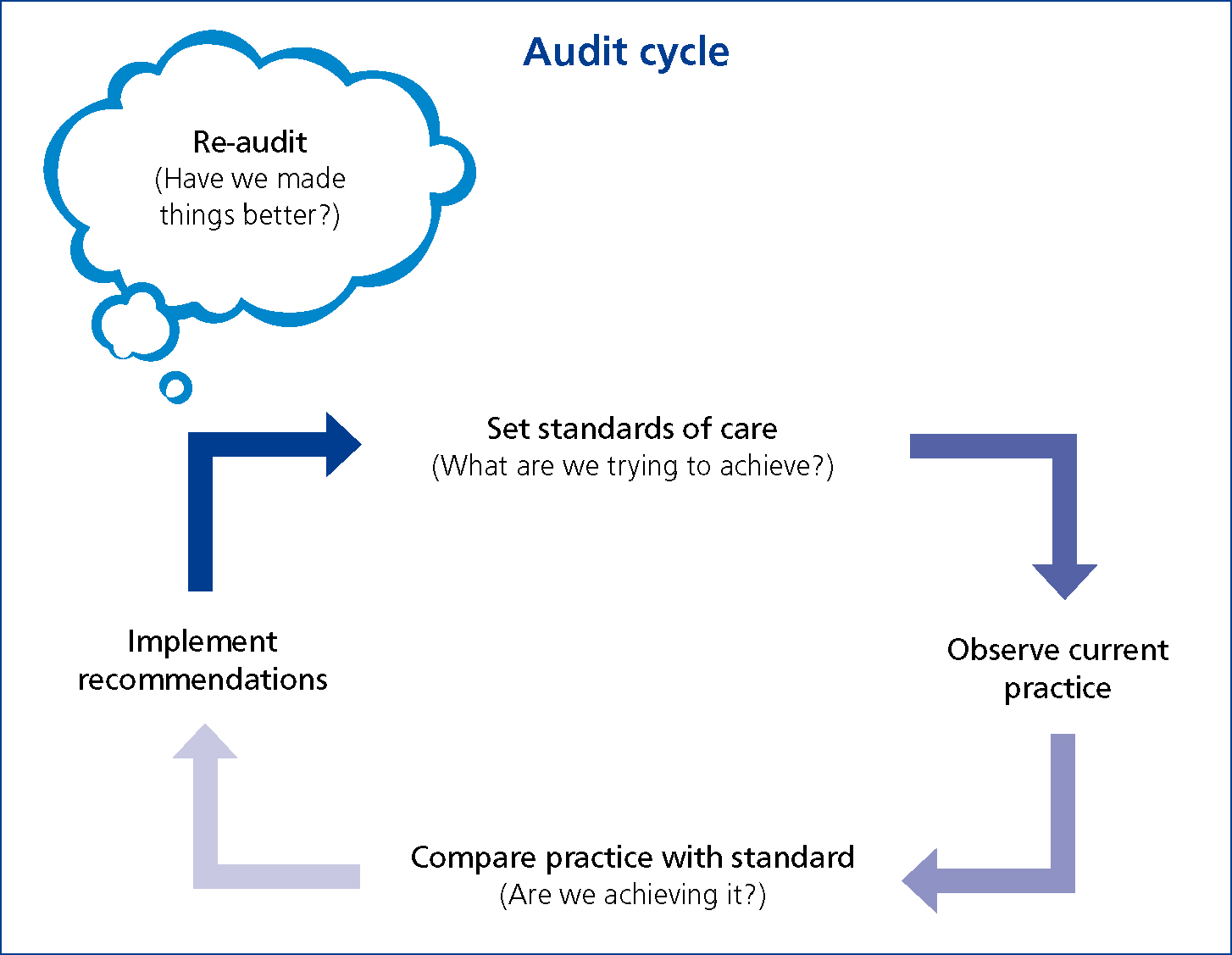

It is therefore suggested that the audit cycle includes an additional re-audit stage (Figure 5). When appropriate, it is important to re-audit as a means of determining whether the improvements and changes implemented as a result of the initial audit are effective. Re-audit also serves to identify whether there are other issues of concern relating to the new practices or changes implemented and, in turn, would lead to the start of a new audit cycle (Rayment, 2002).

Conclusion

As in human healthcare settings, veterinary practices are accountable to their clients, and practitioners are responsible in a professional capacity to provide the highest quality service for their clients and the best possible care for their patients. Clinical audit is a vehicle for improving efficiency and effectiveness, prioritising resources, reducing clinical error and enables review of current practice in the light of recent research, literature and other evidence (Rayment, 2002).

As the infection control audit can be a daunting task, a standardised protocol for the audit process provides a template for an impartial, organised, structured, and thorough review.