A good understanding of fear and its behavioural signals in canine patients can be important to ensure a patient's experience of the veterinary practice is kept as positive as possible. This ensures the welfare of the animals is of a high standard and the safety of all involved is improved. This article looks at how to recognise these behavioural indicators and how to respond to them effectively.

The importance of recognising fear

‘Fear is defined as an unpleasant emotion caused by threat, danger or harm (Oxford Dictionary, 2013). This is a natural response to any perceived aversive stimuli and is related to a natural survival instinct. Learning the relationship between an aversive stimuli and the environmental cues that predict it is essential to survival (Maren, 2001).

Fear-related behaviours are commonplace within the veterinary practice. In a study of 135 cases, 78.5% of canine patients were categorized as fearful (Doring et al. 2009). These fear associations take hold very quickly and develop over time if not dealt with. This means that one negative experience while in practice, if of sufficient intensity to that particular dog, can lead to a lifelong fear of the practice. By looking at the high percentage of dogs within practice that are displaying fear-related signals it becomes apparent how important it is to recognise these behaviours.

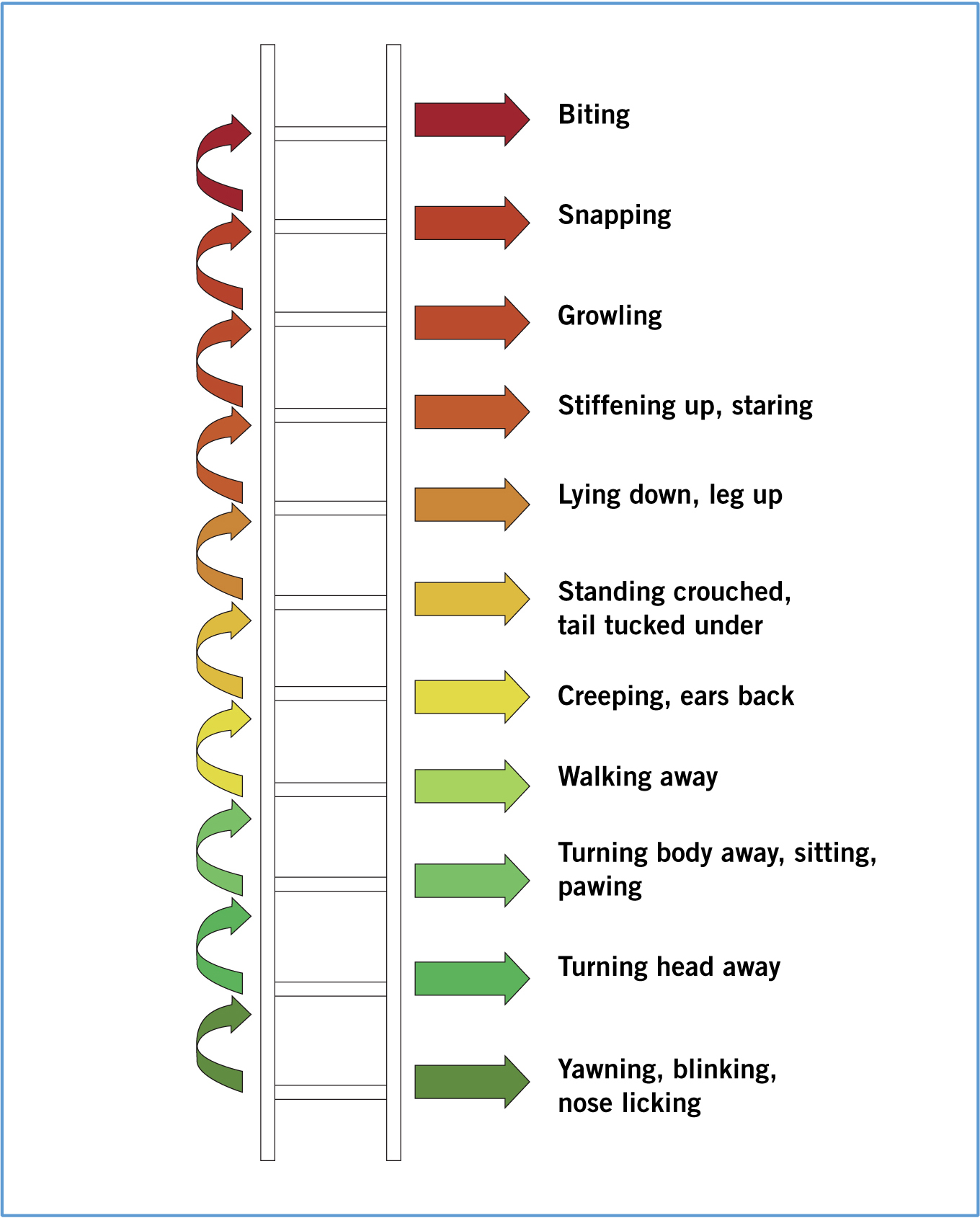

By recognising fear-related behaviours it is possible to create a safer environment for staff and owners, as well as the dog. One of the most common hazards to veterinary staff is injuries caused by an animal (Jeyaretnam and Jones, 2000; Phillips et al. 2008). One study stated that 66% of reported accidents in the veterinary practices that were included in the study were caused by animals (bites, scratches, kicks) (Nienhaus et al. 2005). It has been shown that animals with a history of biting also display fearful behaviours (Guy et al, 2001a; Guy et al 2001b). This highlights how important it is for veterinary staff to have a sound knowledge of fear based behaviour. By being able to recognise the signs of fear staff may be able to avoid aggressive interactions and reduce the likelihood of injury occurring. This is highlighted by looking at Kendal Shephard's Ladder of Aggression. By recognising the initial warning signals steps can be taken to prevent progression up the ladder (Figure 1)

From a welfare perspective it is important to recognise the behavioural signals when assessing the animal's welfare. Christiansen and Forkman (2007) state that the parameters used to assess welfare within a veterinary practice are predominantly clinical but behavioural assessments are just as important. Assessing the patient's interactions with its environment, such as behavioural responses, as well as its physical state is optimal for gaining an accurate assessment of welfare within practice (Odendaal, 1998).

Guidelines that are still used to assess the welfare of any animal that is under human responsibility, and that are advised by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA, 2013), are the Five Freedoms. Number five states:

‘Freedom from Fear and Distress — by ensuring conditions and treatment which avoid mental suffering.’

Fear indicating behaviours

Dogs can develop fear of a certain stimuli for a number of reasons. It has been suggested that certain dogs or breeds may be genetically predisposed or hard wired to react in a certain way however many reactions are learned through experience. It has been seen that it only takes a single exposure to an aversive stimuli for a fear response to be elicited when the stimuli is presented. One study in rats showed that if a conditioned stimulus was coupled with an aversive unconditioned stimulus the conditioned stimulus was then sufficient to elicit a fear response (Gross, 2007). Similar responses can be seen in dogs that develop fear-based responses to thunder or fireworks after one exposure. These responses may then develop over time and subsequent exposures to the aversive stimuli (Landsberg and Horowitz, 1998). In addition, if a patient within the veterinary practice experiences pain via an injection or a procedure the environment, or certain aspects of the environment could then elicit a fear response from subsequent exposures.

In this case the patient will display fear behaviours next time they are exposed to the particular stimulus (the injection or procedure) (Table 2). Such behave-iours have been linked to a physiological response in the dog, such as raised heart rate and cortisol levels, which indicate an increased emotional stress response when a stimulus is perceived as a potential danger. This is linked to the natural survival instinct.

Hydbring-Sandberg et al (2004) showed an increase in cortisol concentration and heart rate was seen in dogs that were classified as fearful of gunshots. Beerda et al (1998) showed that a lowered body posture was seen in dogs that were subjected to a fear-inducing stimuli (sound blast or electric shock). Dogs that were classified as thunder-phobic have been observed by experimenters during controlled experiments to display behaviours such as hiding, remaining near the owner, cowering, shaking. These behaviours were classed as fear behaviours due to the nature of the stimulus (Dreschel and Granger, 2005). These studies showed that lowered body posture correlated with increased cortisol levels and heart rate in dogs, and indicate the correlation between certain behaviours and the physiological response associated with emotional stress or fear within dogs. This provides an ethogram of behaviours that communicate to us that the dog finds a stimulus fearful. This can be seen in Table 1.

| Fear behaviours |

|---|

| Lowered body posture |

| Hiding |

| Remaining near owner |

| Freezing |

| Appear to shrink away |

| Tail tucked underneath the body |

| Ears will be pinned back against the head |

| Pupils may be dilated |

| Slight retraction at the corners of the mouth |

| Trembling |

Recognising the warning signals

Animals have a set of standard responses to aversive or negative stimuli. These are commonly referred to as the Four Fs:

The animal's initial instinct will be to run (flight) or freeze depending on the situation and environment. If the aversive stimulus is too close the Fiddle about response is used. These are a set of displacement behaviours that are used to communicate discomfort or uneasiness with a situation (Table 2) (Figure 2). If these behaviours are ignored or not recognised then the animals only other option is the fight response. This is when aggression problems are seen to occur.

| Displacement behaviours |

|---|

| Lip licking |

| Yawning |

| Holding up of a paw |

| Turning head away |

| Averting eyes |

These displacement behaviours indicate that the animal is uncomfortable with the situation it is in. This is not a strong fear response however it is important to be aware of these behaviours in order to identify when a patient is anxious. It is then possible to implement strategies to make the situation more positive such as praise and food. These are highlighted further on in the article.

Preventative strategies for fearful dogs

As with most problems prevention is always better than cure. One of the causes of anxiety and fear in dogs is the inability to predict its environment or the outcome of a situation. If a dog can predict a positive outcome from an environment it is less likely that a negative response will be elicited from that environment. Offering the client the opportunity to bring in their dogs outside of a consultation setting it is possible to offer more positive interactions with the practice and the staff.

By implementing a socialisation programme, for example, for people registering a dog, of any age, with the practice it is possible to build up positive experiences. Doring et al (2009) found that canine patients that had only positive experiences of the veterinary practice showed significantly less fear-related behaviours and responses than dogs that had negative experiences.

For example the majority of practices have scales in the waiting room. By bringing the dog in on a weekly or fortnightly basis, checking the dog's weight, offering them praise and a treat it is possible to enhance the positive associations with the practice. This can be further enhanced by veterinary staff offering the dog praise and treats to reduce any associations being made with the uniform or particular people. This method is advocated by the American Society of Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA, 2013).

By complementing a consultation with praise and treats veterinary staff can reduce negative associations being made during examinations, injections etc. By pairing a potentially negative stimuli with something appetitive the potential intensity of fear associations may be reduced.

By utilising certain handling and restraining techniques it is possible to reduce the emotional stress the patient is experiencing. In her book Low Stress Handling, Restraint and Behavior Modifications of Dogs and CatsYin (2009) outlines handling and restraint techniques that reduce the level of stress experienced by the patient. This in turn reduces the negative associations that the animal makes with the veterinary environment and impedes on the likelihood of a fear-based response developing. These techniques are outlined in Table 3.

| Greet them in a friendly non-threatening tone |

| Avoid quick movements and go slowly |

| Kneel down to the dogs level and approach from the side |

| If using a muzzle with historically aggressive dogs educate the owners in ways to get the dog accustomed to wearing it. By placing a sticky treat inside the muzzle such as peanut butter or squeezy cheese several days prior to a veterinary visit this can be achieved |

| Treats should be used where they do not compromise the patient's health. It may be benefcial to request the owners withhold a meal so the patient arrives hungry |

| The reward should be given just before the needle stick or other painful procedure and continue until the procedure is over, i.e. 1 dry or semi moist treat such as squeezey cheese or Kong paste every 0.5 second. Each treat will help distract the patient and encourage it to associate the treatment with a reward |

| Support dogs against your body |

| Use non-skid mats and rugs to provide traction on slippery surfaces |

| Hold smaller patients in lateral recumbency for placing intravenous catheters |

| Avoid uncomfortable positions, e.g an arthritic dog may be uncomfortable on its back. |

| Desensitise patients when they are hospitalised by taking time for some general tender loving care |

| Chemical restraint may be needed before a patient becomes too aroused |

Counter conditioning

Counter conditioning is the process of pairing the stimuli that elicits the fear response with something appetitive. An example of this can be seen in a dog that has always been friendly with dogs. The dog gets bitten by a large white dog. The dog then attempts to avoid large white dogs, displaying a fear response. If this is not counter conditioned the dog then general-ises this response to other dogs that resemble a large white dog and if other negative interactions occur a fear of all dogs may develop. If this is transfered to the veterinary environment even if a dog shows no fear of the practice it only takes one negative interaction, such as an injection, to begin this process. By pairing any negatives with a positive, and continuing to do so during every visit to the practice, the liklihood of this process developing may be diminished. Through repetition of pairing a negative stimulus with an appetitive alternative such as praise and treats the dog learns to anticipate a positive outcome rather than a negative one when the stimuli is presented.

If presented with a dog that is already fearful of the veterinary environment, or a certain aspect of it, the methods outlined in the previous section can be used to pair with the veterinary environment to counter condition the dog's response. Rather than expecting an outcome of pain the dog will learn the outcome of reward when the stimuli is presented.

Conclusion

Dogs that have a fear response to the veterinary clinic have the potential to be dangerous to clients, staff and other patients. This fear response can be prevented by pairing the different elements of a consultation with something appetitive including praise. If the fear response is already evident the use of counter conditioning can aid the patient in learning a new response to the stimuli. There are methods that can be implemented to reduce the number or intensity of negative interactions. This reduction in fear association possibilities can improve the safety of all involved as well as improve the welfare of veterinary patients.