Models of nursing were introduced into the field of human nursing in the 1970s and have since become a constant source of discussion. Evidence of continual exploration into the concept of models and their significance is vast and demonstrates the varying degrees of criticism and praise that has been generated by their existence.

This article will briefly look into the concept of nursing theory, the nursing process and nursing models, and how important these concepts are to the development of veterinary nursing as a profession. The article will be a critical discussion of the author's experience of designing and implementing a care plan in practice. Published literature will be examined in an attempt to support or further explain the findings, and the broader implications of these findings for veterinary nursing will be considered.

Veterinary nursing as a profession

Veterinary nursing has come a long way since its beginning in the mid 20th century, from unqualified veterinary assistants to fully accountable registered veterinary nurses (RVNs). It is still, however, not clear whether RVNs are truly professionals in their own right or whether the public and even other members of the veterinary profession will forever view them as the veterinary surgeon's assistant. One way veterinary nursing can enhance its professional status is to take ownership of the unique skill set that sets it apart from veterinary medicine — this is where nursing theory, the nursing process and nursing models become relevant. These are all terms that have originated from human nursing but are easily transferrable to the veterinary nursing vocation.

Historical accounts of the development of human nursing indicate that RVNs have followed a very similar pathway to that of registered nurses (RNs) (Keddy et al, 1986) although it is thought that the advancements and trends in veterinary medicine in general are some years behind human medicine (Hancock and Schubert, 2007). When introducing ideas that will help to shape veterinary nursing practice it is, therefore, sensible to look at the opinions and conclusions that have been drawn from human medicine development.

Nursing models

A nursing model consists of the components or ideas that help make up what nursing is — the theories, the beliefs and values, the concepts and the processes (Pearson et al, 2004). A model describes the details that the nursing process lacks, that is: what to look for when assessing, what form the care should take when in the planning stage, what particular interventions may be appropriate, and what to base the evaluation on (Aggleton and Chalmers, 2000). There are many different frameworks which make up a number of models, these frameworks base themselves on various theories and concepts about different sets of individuals and what causes good and ill health (Aggleton and Chalmers, 2000).

Design and implementation of the care plan

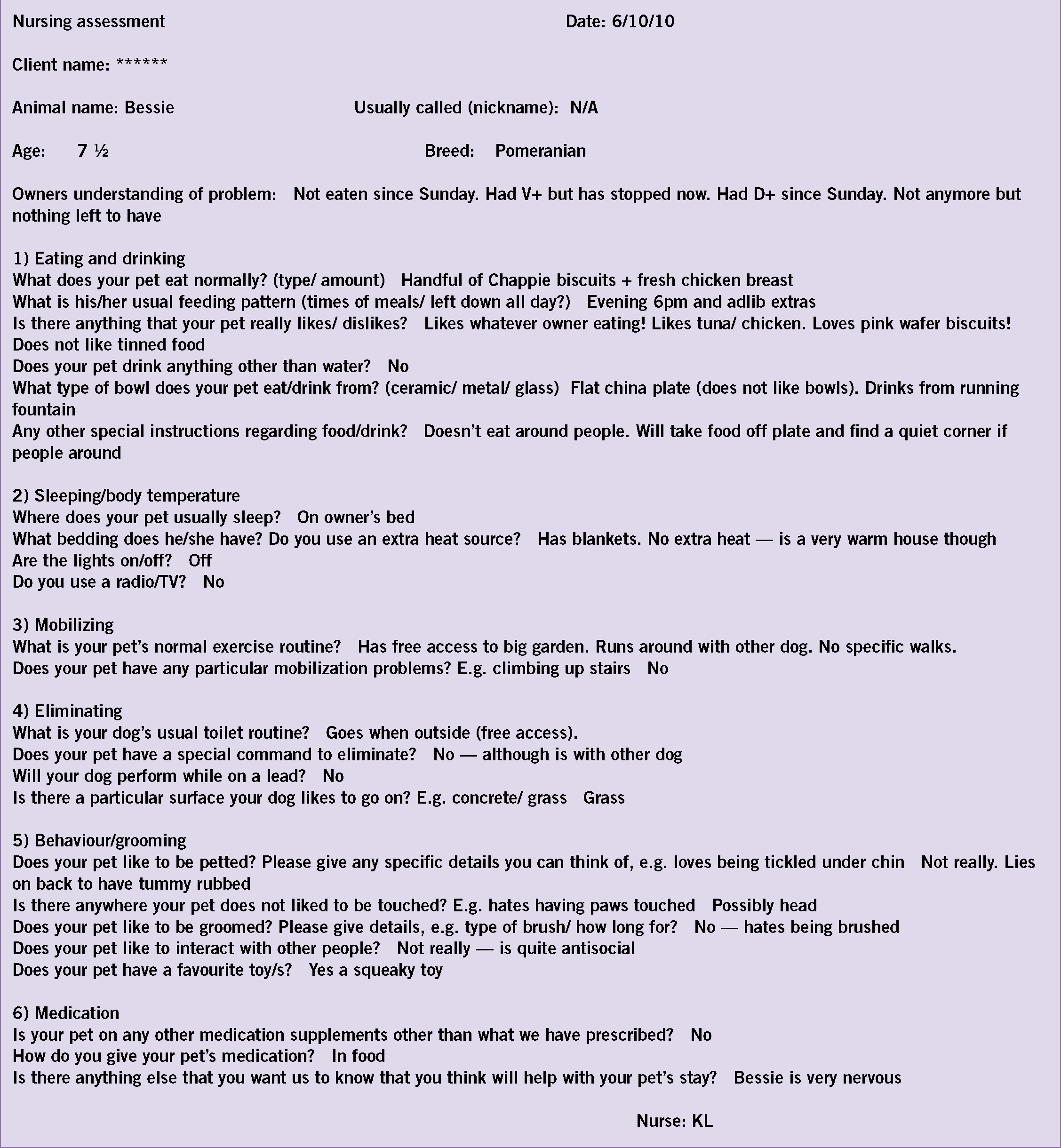

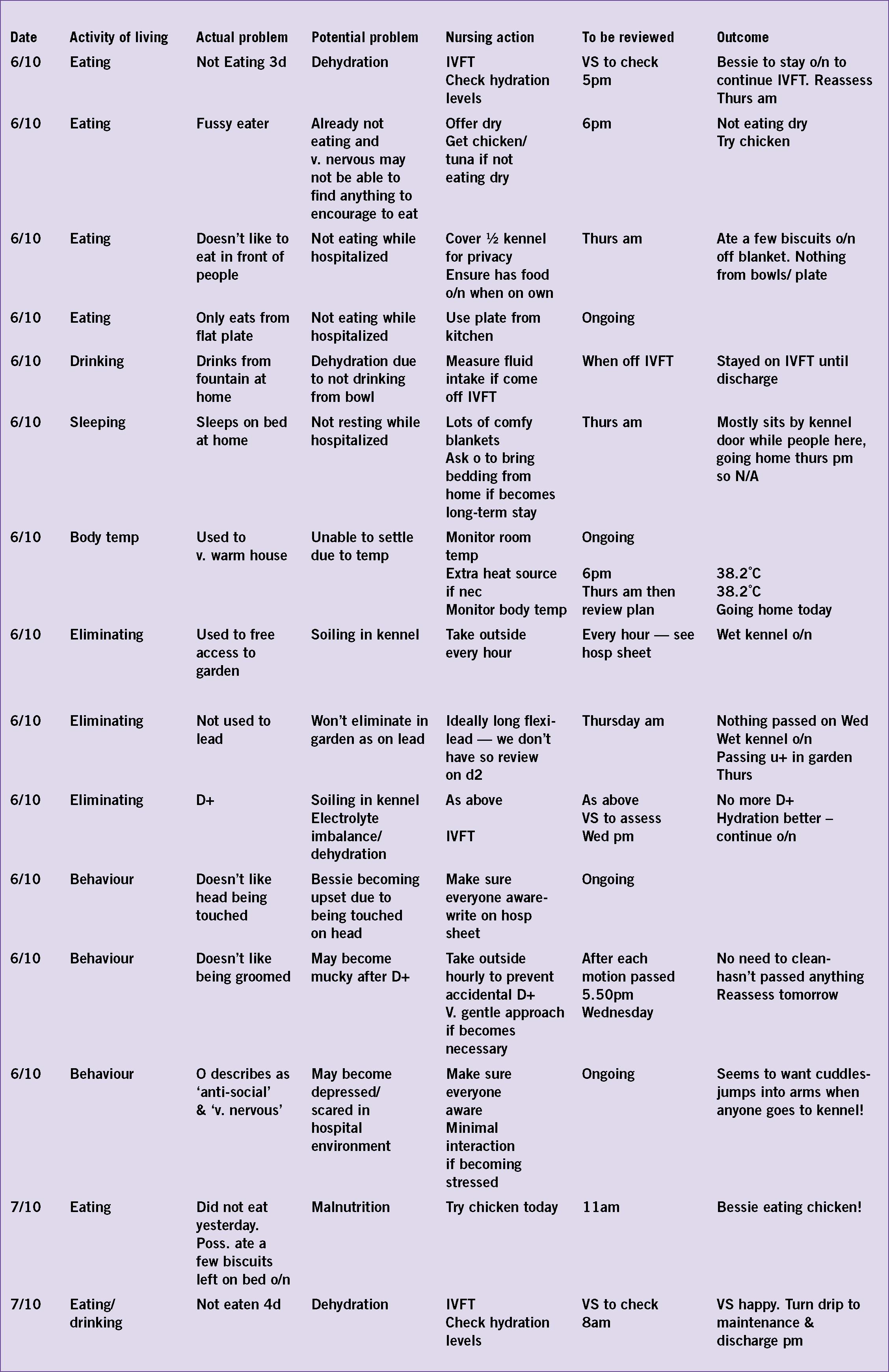

The author designed a care plan to use in practice, using an adaptation of (Orpet and Jeffery's Ability Model (2007) as this is the only model currently designed for veterinary use. A patient assessment form was designed as a questionnaire to interview the owner of the patient (Figure 1). The author believes that the personal bond this creates between the owner and the RVN is important, both for enhancing the level of care that will be provided to the patient and its owner, and to demonstrate to the public the vital role of the RVN. Research carried out by Lue et al (2008) found that the biggest factor that encourages an owner-veterinary surgeon bond (or RVN in this case) is communication. The level of communication during a one-to-one interview process is high. This means the likelihood of being able to pick up on any misunderstandings or worries that the owner has is increased which, in the author's opinion, far outweighs a less personal approach, such as a written questionnaire that the owner fills out. The questionnaire was broken up into sections relating to the different activities of living which made it easy to transfer to the care plan (Figure 2).

Studies carried out in the human nursing field reveal that a frequent complaint of care plans is the time taken to complete them (Mason, 1999; Gerrish et al, 2007). With this in mind the author's care plan was adjusted in several ways. The ‘short-term goal’ section was removed as even though the goal is an essential part of the nursing process, documenting it seemed to produce repetition as the goal is generally to prevent or alleviate the potential or actual problems, which are documented in the care plan. The ‘nursing actions’ section is important as it allows the nurse to enter the way they will prevent problems arising, in other words, achieve the goal. For example, a potential problem of a dog with diarrhoea would be dehydration and becoming soiled. The goal would simply be to prevent these events from occurring. To ensure the nurse in charge knows what to do, the nursing action would need to be stated, which in this case would be to monitor hydration status and take the dog out for regular visits to the garden.

The care plan was used to nurse ‘Bessie’ a 71/2-year-old Pomeranian admitted to the surgery for anorexia following several days of vomiting and diarrhoea. The owner was interviewed and the care plan was formulated using the information that was gathered (see Figure 1). All the nurses that would be caring for Bessie read through the assessment and care plan but were given no further instructions so the author could gauge how easy it was for the plan to be picked up and used unguided. The care plan was implemented for the entirety of Bessie's stay which was approximately 30 hours. The nursing interventions were modified when needed following an evaluation of Bessie's progress, but this did not involve a lot more writing than would normally be required to update the day hospitalization charts that are currently in use in the author's practice.

Discussion of the care plan and results of its use

A solitary trial of the care plan indicated that it was highly beneficial to Bessie and to the nurses who were involved. Bessie's recovery was rapid and the primary aim of getting her to eat was accomplished. This was achieved as a result of the care plan identifying at an early stage that Bessie had a fondness for fresh chicken; as fresh chicken is not something that is kept at the practice, without the care plan it may have been some time before this information was obtained, either after eventually phoning the owner or by chance, having offered many other foods first.

The care plan allows the nurse to create an environment that aims to minimize stress for the patient by gaining knowledge of their home environment and routine, and integrating these into the practice wherever possible. Keeping stress levels to a minimum is vitally important to hospitalized patients as elevated stress levels increase the cortisol production in the body, which has been shown to slow the healing process (Ebrecht et al, 2004; Christian et al, 2006). Stress is also likely to prevent the animal from wanting to eat or rest (Delaney, 2006; Jeffery, 2006). In Bessie's case it was also really useful to know that she only ate from a flat china plate as this is not something the practice would offer routinely. The owner also informed the author during the initial assessment stage that Bessie never ate in front of people; this meant the veterinary nurses did not stand over her and expect her to eat, but instead offered her a hidden area and left her alone after offering her food.

Compartmentalization of patients

Information gained during the interview process, using the nursing model, enabled the author to move away from the medical model, where the patient is treated for the disease it has, and allowed an understanding to be gained of the patient as a whole (Jeffery, 2006). This process revealed extensive information about Bessie (as discussed above) that would almost certainly have been overlooked otherwise and some of which was undoubtedly crucial in providing a more holistic plan for Bessie's care (Orpet and Jeffery, 2006). What was interesting in Bessie's situation was that the client was adamant that Bessie was of a very shy and unsociable disposition and disliked to be handled. This had resulted in the care plan being written with warnings of minimal handling and maximum privacy for the dog. The reality actually turned out to be quite different, in that Bessie appeared to want a lot of close physical contact and was much happier to be seeing what was happening in her surroundings than to be secluded. This realization brought to light the importance of the nurse assessment as a separate component of the process to the client questionnaire. It raised the concern that if followed too rigidly, with the absence of using other nursing methods, the care plan could possibly be detrimental to the animal's care. Heath (1998) highlights the issues raised by the rigid approach to nursing and describes nursing care as becoming too prescriptive rather than reflective in its approach. McHugh (1987) went as far as to say that the nursing process handicapped experienced nurses and it was an unnecessary waste of time and a study carried out by Hurst et al (1991) concluded that it was inappropriate for nurses to have one set approach to problem solving as traditionally they were using a variety of methods. This suggests the more traditional opinion of nursing having an intuition-based approach is an important notion that should not be totally dispelled and where possible should be incorporated into the nursing process.

Teamwork

Teamwork is an extremely important component in the success of care plans in practice requiring time, understanding and commitment from all involved (Cory, 2007). In the present study this was demonstrated by the variation in receptiveness from different members of the nursing staff. It was found that the junior members of the team were more eager to participate in the use of the new care plans than the more senior nurses who were less willing to adopt this new way of caring for their patients. This notion is supported by various authors and studies that have shown that junior nurses benefit more from care plans than more senior nurses as they provide them with the structure and clarity that they need given the experience that they generally lack (McKenna, 1994; Heath, 1998). With this comes more negative feedback from senior nurses who dislike feeling they are being told how to do something they are already well accomplished in (Wimpenny, 2002). Studies have also found that senior nurses have a greater influence when it comes to getting new protocols and systems implemented in practice, which highlights the difficulties that could arise if these nurses are not on board with a new initiative (Mason, 1999; Gerrish et al, 2007). One way to encourage commitment to the implementation of care plans in practice is to ensure that all nurses are involved in the planning stages, thus gaining ‘local ownership’ of the plans (Mason, 1999). Higher success rates have been found, when those being asked to implement a new way of nursing do not feel it has been ‘imposed from above’ without former discussions regarding its arrival (Mason, 1999; Wimpenny, 2002). This way of implementation also has the benefit of nurses having a greater understanding of what they are doing and why they are doing it, which in turn means the care plans can be implemented to a higher level, creating better outcomes for the patients (Jerving, 1994; Heath, 1998; Wimpenny, 2002; Timmins and O’Shea, 2004).

Broader implications for veterinary nursing

According to the 2010 Royal Collage of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) Survey of the UK Veterinary Nursing Profession (Robertson-Smith et al, 2010), RVNs gain most of their job satisfaction from building client relations, working with animals and making a difference. Care planning provides a medium that allows RVNs to encounter these areas of their work on a more regular basis, which in turn could meet their desires for more responsibility and more respect, which were named in the survey as the top suggestions to improve the profession. A study by Tzeng et al (2002) demonstrated the relationship between organizational culture of a workplace, job satisfaction and patient outcome, and found that each one has a positive outcome on the next; therefore a well-implemented care plan could not only improve nurse job satisfaction but in turn improve patient outcome. This may have the broader implication of creating more satisfied clients, which can only be positive for practice owners.

Greater utilization of RVNs by allowing them a greater involvement in inpatient care and client communication is sensible from a business point of view. According to Hancock and Schubert (2007) this is something that is greatly underdeveloped in veterinary medicine compared with the medical profession and their use of paraprofessionals. They explain the financial implications of overloading the veterinary surgeon, whose time is most expensive and often most limited, and the impact that this has on the cost of care to the client. Perhaps more importantly for the RVN, the article also stresses the personal benefit of being better utilized, that is the ability to make use of the extensive skills that are possessed, but are often unused, due to lack of opportunity. By playing a more obvious role in the economics and public image of the practicethe author believes that RVNs will start to feel the respect that is due to them from both their colleagues and the general public.

However, the success of care plans in human nursing is debatable and there is some controversy as to whether they benefit the patients or are merely designed to enhance professional status (Heath, 1998). Some feel they have forged a divide between the academics of the nursing world and those who actually do the nursing; they feel the dogmatic approach to their implementation makes them impossible to apply and leads to a distraction of the care that needs to be provided rather than the support they were designed to provide (Heath, 1998; Griffiths, 1998). Enhancing professional status is for many the ultimate aim, but if this is at the detriment of job satisfaction and patient outcomes then perhaps this is not the approach that will improve the profession as intended.

The author's views on care plans

Care plans were incorporated into the veteriary nursing syllabus in 2006 and the author was among the first student veterinary nurses to be taught this ‘patient-focused approach to nursing’ (Pullen and Bowden, 2006), prior to carrying out this research. The initial experiences had created negative feelings about their use because of a lack of understanding. As discussed above, this finding is not uncommon and as reiterated by Heath (1998),Jerving (1994), Wimpenny (2002) and Timmins and O'Shea (2004) it is vital that those who implement the care plans have appropriate training to ensure that they have total understanding of the subject. This will not only increase the user's positive feelings towards the care plan but also greatly increases the chances of successful implementation. It is also imperative to realistically look at the setting the new initiative is being introduced into, in this case the author's practice, and make an assessment of what will and will not work in the particular situation (Mason, 1999; Grol, 2001). In this instance it was felt that using a model to guide the nursing assessment interview would greatly enhance the holistic care provided in practice, but that the remainder of the care plan process, although highly beneficial, might be unfeasible given the time it takes to complete. Instead the information from the interview will be used to enhance the use of the hospitalization charts currently in use.

The medical model is still predominantly used in human-centred nursing rather than the holistic style that the care plan encourages (Griffiths, 1998). The encouragement of a holistic style of nursing is, in the author's opinion, the most valuable asset that can be gained from care plans. It provides nursing with a direction that can become obscured by the medical model approach that is most common among veterinary surgeons. At a time when nearly half of RVNs planning to leave the profession give as the main reason for dissatisfaction not feeling valued (Robertson-Smith et al, 2010), a fresh approach to nursing appears to be much needed.

Conclusion

This article has reflected on the author's own experiences of implementing a nursing care plan in practice. The author found that care plans have the potential to improve the care provided to patients by considering the patient as a whole and therefore moving away from the medical model. To improve the chances of successful implementation, team involvement and thorough training is strongly recommended. It is uncertain whether the introduction of care plans will provide the medium to allow RVNs to be fully utilized and create their own skill set. Identification of the strong and weak points of human nursing care plans should provide a guide to aid successful implementation of care plans into the veterinary profession. For example, taking a less rigid approach and allowing room for more traditional intuition-based nursing to be incorporated, the nursing model can be used as a tool to enhance ideas and concepts rather than as a mode of dictation.