Clinical symptoms of renal dysfunction (polydipsia, polyuria) are not evident until a large portion of renal tissue has been destroyed, until then many cases can remain undiagnosed. Chronic renal failure (CRF) has many physiological effects, these include the decreased ability to excrete nitrogenous waste (and thus build-up of azotaemia), sodium and phosphorus, and an increased loss of potassium and water-soluble vitamins. Other clinical symptoms also include systemic hypertension, secondary hyperparathyroidism and non-regenerative anaemia (Lane, 2005), these aspects should therefore be monitored as part of the nursing clinic.

Most veterinary practices offer owners renal screening for older patients, as part of senior clinics, pre-anaesthetic screening or before the start of pharmaceutical regimens (such as osteoarthritis treatments).

Early identification of these CRF cases is required in order to establish management of the different stages of CRF. Guidelines set out by The International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) help to establish the types of management that are required at the different disease stages. These guidelines can be utilised as part of care bundles to formulate a nursing care plan (NCP) (Box 1).

Box 1.Definition of care bundles and plansCare bundle — group of evidence-based best practices related to a disease or set of symptoms, that, when executed together, result in better outcomes than when implemented individually (Norman, 2010).Nursing care plan (NCP) — the written record of care planned and implemented for a particular patient (Barrett et al, 2012).

Diagnostics for staging

Initially renal failure was diagnosed with serum concentrations of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine, however tests for symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) have been shown to detect CRF in cats on average 17.0 months before serum creatinine concentration increased above the reference interval (Hall et al, 2014). SDMA monitoring is available for in-house analysis, these can be obtained from Idexx Laboratories.

The IRIS renal scoring index identifies the progression of the disease in order to facilitate appropriate treatment and monitoring of the patient. The initial staging is based on a fasted plasma creatinine level, SDMA and then substaged dependent on proteinuria levels, and arterial blood pressure (Table 1).

Table 1. IRIS staging of chronic renal disease in cats and dogs

| Stage 1 No azotaemia (normal creatinine) | Stage 2 Mild azotaemia (normal or mildly elevated creatinine) | Stage 3 Moderate azotaemia | Stage 4 Severe azotaemia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine in mg/dl Stage based on stable creatinine | Canine | <1.4 (125 μmol/litre) | 1.4–2.8 (125–250 μmol/litre) | 2.9–5.0 (251–440 μmol/litre) | >5.0 (440 μmol/litre) |

| Feline | <1.6 (140 μmol/litre) | 1.6–2.8 (140–250 μmol/litre) | 2.9–5.0 (251–440 μmol/litre) | >5.0 (440 μmol/litre) | |

| SDMA* in μg/dl Stage based on stable SDMA | Canine | <18 | 18–35 | 36–54 | >54 |

| Feline | <18 | 18–25 | 26–38 | >38 | |

| UP/C ratio | Canine | Nonproteinuric <0.2 Borderline proteinuric 0.2–0.5 Proteinuric >0.5 | |||

| Feline | Nonproteinuric <0.2 Borderline proteinuric 0.2–0.4 Proteinuric >0.4 | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure in mmHg Substage based on blood pressure | Normotensive <140 Prehypertensive 140–159Hypertensive 160–179 Severely hypertensive >_180 | ||||

SDMA = symmetric dimethylarginine; UP/C = urine protein creatinine.

Note: In the case of staging discrepancy between creatinine and SDMA, consider patient muscle mass and retesting both in 2–4 weeks. If values are persistently discordant, consider assigning the patient to the higher stage.

*SDMA = IDEXX SDMA Test.

See www.iris-kidney.com for more detailed staging, therapeutic and management guidelines.

Fasted blood samples should be recommended as even a moderately high protein meal prior to sampling can elevate blood plasma creatinine levels. SDMA is unaffected by fasting times, or body condition score, so can be a more reliable marker to use. Repeat blood sampling should occur, as required, but should be performed more regularly if urinalysis shows changes in proteinuria levels.

Some owners can find obtaining urine samples difficult and guidance on alternative methods (hydrophobic sand or plastic pebbles) for obtaining these samples should be offered, as these are the most useful diagnostic tools for determining the progression of renal failure. Urine concentration should be routinely measured with the use of a refractometer. The urine protein creatinine (UP/C) ratio, should also be measured as required by the veterinary surgeon overseeing the case. Medications such as angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors should only be instigated when proteinuria is present. It should be noted that proteinuria can present at any stage of renal failure and is not directly linked to the level of azotaemia.

Renal function is directly affected by an increase in blood pressure, and as the kidneys play a role in blood pressure, secondary hypertension can result in patients with CRF. Hypertension should be treated, as the effects of hypertension are ultimately negative. The aim is for the systolic blood pressure below 140 mmHg (Table 1), as target organ damage can occur over this value (Table 2).

Table 2. List of possible target organ damage as a result of hypertension

| Target organ | Possible manifestations due to prolonged hypertension |

| Heart | Left ventricular hypertrophy, heart failure |

| Brain | Transient ischaemic attack (TIA), stroke |

| Kidneys | Renal failure |

| Retina | Exudates or haemorrhage |

| Peripheral vasculature | Absence of major pulses due to thromboembolism |

The frequency of testing will depend on the practice, the owner and the progression of the clinical signs. The care bundles should provide guidelines on regularity of expected monitoring schedule.

Management of chronic renal failure

The management of CRF can be split into nutritional and pharmaceutical regimens, alongside regular monitoring schedules (Table 3).

Table 3. Treatment recommendations from IRIS dependent on the staging

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

UP/C = urine protein creatinine.

Pharmaceuticals

In cats with chronic renal insufficiency ACE inhibitors such as benazepril are commonly used. ACE inhibitors reduce the protein loss in urine and reduce systemic and intraglomerular blood pressure. As ACE inhibitors decrease the intraglomerular blood pressure there will be a refractory increase in nitrogenous waste products. Benazepril is therefore only indicated when proteinuria has been shown to be present, and therefore should be tested for.

Telmisartan is an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) that is also licenced for the reduction of proteinuria in cats that have chronic renal insufficiency. ARBs are a relatively new class of drug in the veterinary market, and have the benefit of blocking the last step of the renin-angiotensin pathway, and thereby, inhibit the harmful effects of angiotensin II in a target specific manor, as opposed to the non-specific action of ACE inhibitors (Burnier and Brunner, 2000).

In cases where the animal is hypertensive but not necessarily demonstrating proteinuria, amlodipine may be prescribed by the veterinary surgeon. Once instigated, blood pressure monitoring is required in order to taper the dose according to the patient's readings; this is an important aspect of the nursing clinic. Medication doses can only be altered by the prescribing veterinary surgeon, so acting as an advocate for the patient and the client is vital.

If medications are prescribed for patients with CRF it is important that the veterinary nurse discusses with the client in clinic whether they are able to medicate their pet or not. Owners may need guidance on the administration of medications, and on the importance of compliance.

Clinical nutrition

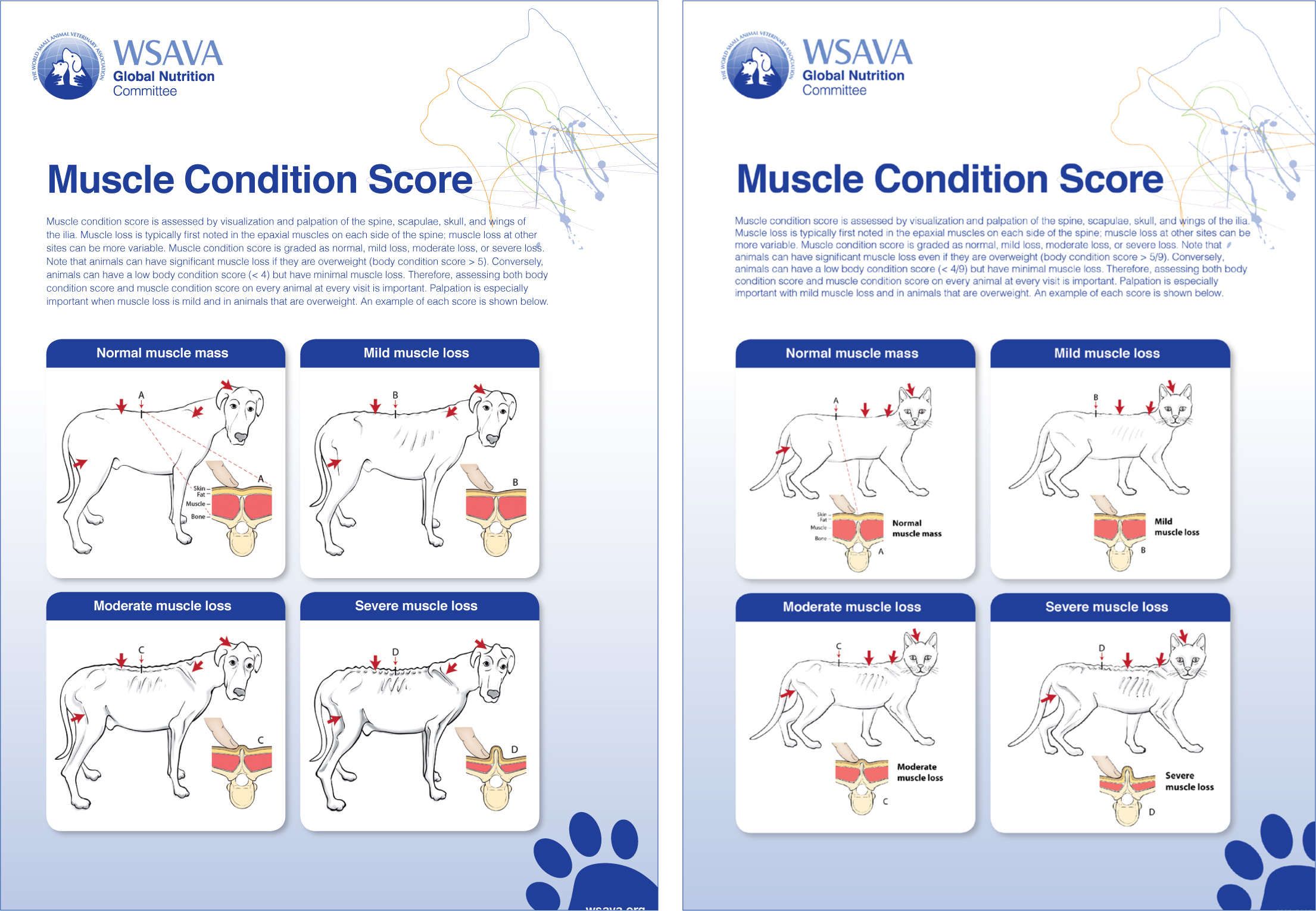

Diet plays an important role in the longevity and quality of life of the animal (Plantinga et al, 2005). Diet has been shown to be the most important aspect in the management of animals with CRF (Elliott et al, 2000). A nutritional assessment of every animal should be performed at every consultation with the patient (Freeman et al, 2011). This includes nutritional history, weight, body condition score (BCS) and muscle condition score (MCS) (Figure 1). By understanding the ideal nutrient requirements for an animal with renal failure, and at each IRIS stage, guidance can be offered when owners wish to prepare homemade diets or feed a non-renal lifestage commercial diet with added phosphate binders. In a study conducted by Hall et al (2016) it was suggested that non-azotaemic cats with elevated serum SDMA (early renal insufficiency) fed a food designed to promote healthy ageing were more likely to demonstrate stable renal function compared with cats fed the owner's choice foods. It was added that cats fed owner's choice foods were more likely to demonstrate progressive renal insufficiency.

Water

Renal disease causes a progressive decline in urine concentrating capacity. Dehydration, volume depletion, renal hypoperfusion and dietary salt intake stimulate urine concentration. Avoiding dehydration and renal hypoperfusion reduces the work of the kidney in concentrating the urine and helps to maintain intrarenal protective mechanisms. CRF patients must have unlimited access to fresh water and free choice of consumption. This can be exceptionally important in cats, which do have fastidious drinking habits. Increasing water consumption can be achieved in a number of different ways including feeding a moist diet rather than a dry diet, and by increasing the availability of water.

Increasing the number of bowls (including types) around the house and allowing water to stand for a period of time prior to being offered can be beneficial to some animals. This allows the chlorine in the water to evaporate off, which some animals do prefer. Phosphate free hydration broths can aid in increasing calorific intake alongside hydration without an increase in phosphate. It is important to discuss with the client how to monitor hydration levels as part of the nursing clinic. Demonstrating monitoring of clinical signs can help the client in the care of their pet. This can include testing for skin tenting, tacky mucus membranes and the colour of membranes. If pet owners know what is normal, when the animal becomes unwell or the renal disease progresses, they can flag this to the practice quickly, ultimately increasing the welfare for the animal.

Feeding a renal diet

Objectively, the role of renal veterinary diets is to help reduce azotaemia, hyperphosphataemia and to control secondary hyperparathyroidism — ultimately improving both the clinical and biochemical status of the animal. A reduced dietary intake of the veterinary diet has often been blamed on its palatability. The effect of uraemia on the sense of taste and smell and the development of food aversions can all contribute greatly towards inappetence. Changing any animal from a high salt, high protein diet to a commercial renal diet can be very difficult. Changing via a transitional intermediate diet over a prolonged period of time (usually 3–4 weeks) can be beneficial in those changing to a renal diet.

Nursing care plans

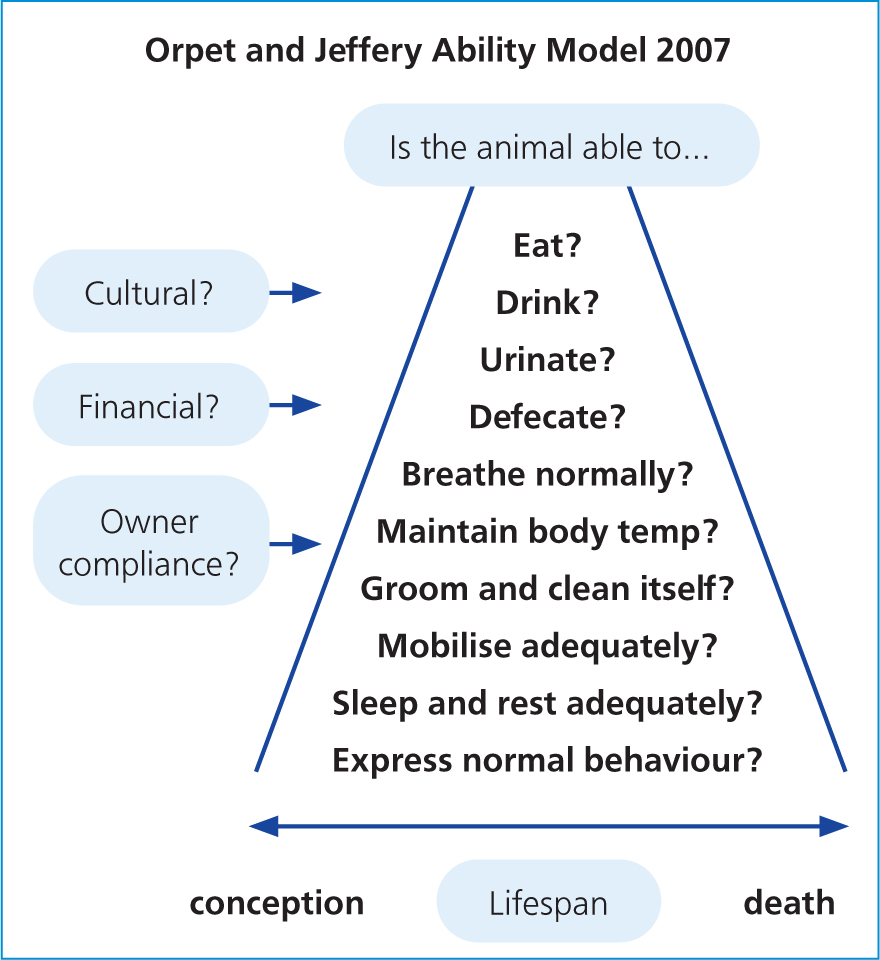

The NCP needs to be written in conjunction with the pet owner (and all other caregivers). Nelson and Welsh (2015) described an initial interview assessment with the owner in order to design the NCP around the details that are provided. Three NCP models are utilised in veterinary nursing: Logan, Roper and Tierney (LRT) model; Orem's model and the Ability Model which is often referred to as the Orpet and Jeffery Ability Model (OJAM) (Orpet and Jeffery, 2007) (Figure 2). In the author's experience the Ability Model fits in easily with the nursing consulting experience (Table 4). Involvement of the owner is vital when completing the model as it enables the veterinary nurse to ensure that the cultural, financial and owner compliance elements are attended to.

Table 4. Considerations for a renal patient when using the Ability Model

| Activity | Problem | Short-term goal and intervention | Long-term goal and intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eating | Can be inappetant due to azotaemia Need to ensure eating sufficient amounts Perform weight checks, body condition score (BCS) and muscle condition score (MCS) regularlyWhat is the animal's preferences regarding diet? | Maintain bodyweight, calculate resting energy requirement and diet intake requirements Transition over to appropriate diet for IRIS stage of renal disease (Table 3)Advise on encouraging to eat | Improve BCS and MCS Feeding renal diet +/- phosphate binder depending on IRIS stage |

| Drinking | Polydipsia due to polyuria, but also possible dehydration | Ensure drinking enough to maintain hydration Show owners how to monitor hydration levels Show owners techniques to increase water intake | Use of phosphate free hydration brothsIf unable to maintain hydration might need to look at supportive methods of fluids, e.g. subcutaneous |

| Urination | Polyuria | Ensure owners are aware of increased frequency of urinationMore walks (if canine), access to outside, more litter trays (if feline) | Supplementation of water-soluble vitamins, especially B12 may become required, as lost in the urine |

| Defecation | Constipation can become an issue if dehydrated | Ensure animal is passing faeces normally Might need to include stool softener if stools become hard due to hydration levels | Mobility might be an issue in some animals — not able to get in/out of cat flaps or litter trays; or to posture to pass stools |

| Breathing | If anaemia becomes severe, respiration can increase | Show owners how to monitor mucus membrane colour | |

| Temperature | As cachexia may develop maintaining body temperature becomes more difficult | Maintaining BCS and MCS Ensure bed is out of draughts, more warm bedding | |

| Mobility | Renal function does not affect mobility, but many older animals will suffer from osteoarthritis | Chronic pain scoring to ensure not in discomfort Advise owner on adaptations to the animal's environment to help with mobility | Continue with pain scoring — act as advocate for patient/owner |

| Grooming | When unwell animals might not groom themselves as muchMight not be able due to mobility, uraemic ulcers in mouth, dehydration | If polyuria — check for soiling. Hair might need clipping away for hygiene reasonsIf any hair matting — might need clipping hair off |

Conclusion

Diagnostics will enable the veterinary team to determine the patient's stage of renal failure. Care bundles, guidelines or protocols that have been created by the practice, corporate group, medical or species interest group can then be implemented, using the recommendations from IRIS for each stage. During nurse clinics, the long-term care of animals with CRF can be discussed with the owner and a NCP that is individualised for that patient can be drawn up. Reference back to the practice guidelines, protocol, care bundles can be made in order to give guidance on what needs to be included.

KEY POINTS

- Renal staging is important in animals with chronic renal failure (CRF) as it helps give definitive points for management (diet) and blood phosphate levels.

- The definitive stages allow registered veterinary nurses to write care plans around the animal, alongside the flow charts provided by The International Renal Interest Society (IRIS).

- Care bundles can really help offer guidance for all staff members and increase continuity of care between individuals within the same practice.

- Care plans, created around the individual, ensure that the best adapted medical management is provided for the renal patient.