The first part of this paper was published in the March issue of The Veterinary Nurse. This second part deals less with the reasoning and reported benefits of writing and publishing veterinary nursing patient care reports (PCRs), which was discussed in the first article in March. Part two aims to provide readers with a more practical guide to how PCRs in veterinary nursing might be structured and set out and offers a model of nursing as a way of helping potential authors focus their discussion section on issues relating directly to the nursing care which was or which could have been provided to the patient.

Guidelines for section headings

Title page

The title page should contain the title of the PCR which should aim to provide a concise and accurate overview of what the PCR is about (of about eight to ten words in length). As discussed in part 1, the authors suggest using title vocabulary which includes the words ‘patient care report’ rather than ‘case report’ as a way for veterinary nurses to foster a more patient focussed approach (Welsh and Orpet, 2011). For example:

A patient care report of patient undergoing celiotomy for removal of foreign body obstruction from the jejunum or

Nursing care provided to patient following celiotomy for removal of foreign body: a patient care report.

Author details

In medical and veterinary case reports, it is unusual for more than two people to be listed as authors although other contributors may be acknowledged at the end of the article (Budgell, 2008). The name of the author/s (with first names or initials) should be provided with details of the author's job role and institutional or clinical practice name and address.

Abstract

Abstracts are used in published material as a way of enabling anyone browsing databases such as Pubmed or ISI Web of Knowledge to gain a little more detail about what the article is about and help them to decide if they should acquire the entire article (White, 2004). An abstract for a PCR should provide a brief narrative overview of the article, and could include the patient's problem/s and identification of the associated nursing implications and conclusion. In general, an abstract for a PCR should contain approximately 75–150 words.

Key words

Four to 6 key words should be provided which represent the focal words which might be used by potential readers when searching for articles via databases.

Signalment

The signalment provides a brief description of the patient (while maintaining client and patient confidentiality). For example:

Species: Canine

Breed: Irish Setter

Age: 12 years old

Sex (and neutered status): Male (entire)

Weight: 25 kg

Reason for admission/presenting clinical problem

This section should contain one or two sentences or a short paragraph giving a brief description of the why the patient was admitted. For example:

This patient presented to the hospital with a history of vomiting followed by anorexia, lethargy and depression of some 10 days' duration.

Patient assessment

This section should contain several sentences to describe any relevant information gained from the client (e.g. during patient assessment questionnaire) and from a nursing and/or veterinary clinical examination. For example:

On physical examination the dog presented with palpable fluid filled viscus in the cranial abdomen. He was lethargic, had a weak, thready pulse, pale and dry mucus membranes and there was a delay in skin fold return with reduced elasticity of the skin.

Veterinary investigations

The results of any diagnostic tests (e.g. bloods, radiographs) may be provided in this section, however, rather than writing long lists of results, it is advisable to comment on the relevance of any abnormal results. For example:

The dog was admitted to the hospital, a blood sample obtained immediately revealed a packed cell volume (PCV) of 54% and total protein (TP) of 85 g/l, indicating a degree of dehydration. A conscious plain lateral abdominal radiograph revealed a fluid filled small bowel loop with a foreign body obstruction identified as a peach stone.

The following day, a pre-anaesthetic examination revealed temperature, pulse and respiratory rates within the normal limits. Following 24 hours of intravenous fluids, the patient's hydration status had improved with a PCV of 45% and TP of 70 g/l.

Discussion of nursing interventions

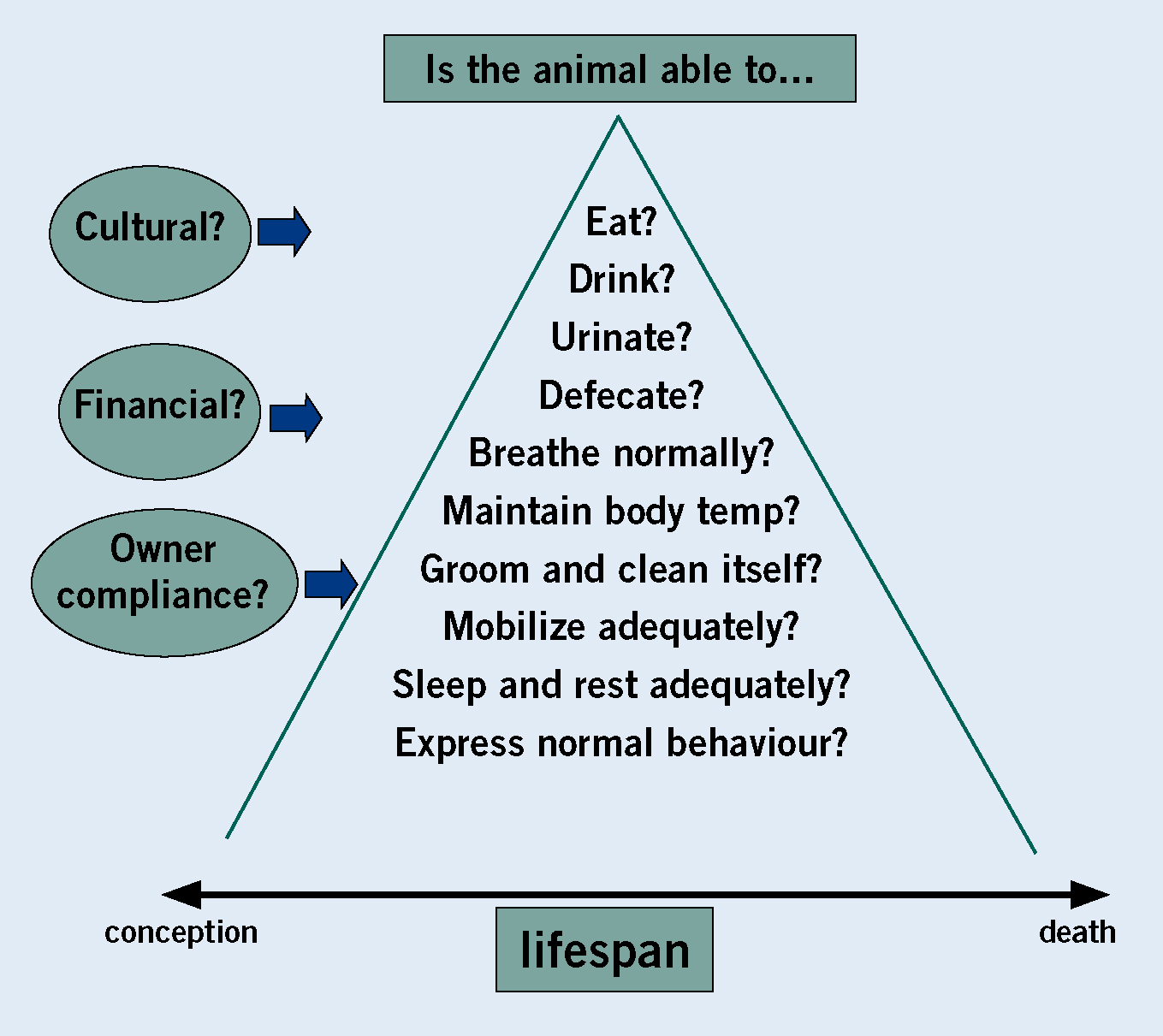

Information prior to this section is largely descriptive but concise. The discussion section should contain at least 50% of the total word count. This section should contain justification and discussion about why particular nursing interventions were instigated and provide evidence to support the clinical conclusions and decisions made. Veterinary nurses should not dwell on aspects of the patient care that would be considered the responsibility of the veterinary surgeon. This section must include reference to published work from up to date, authoritative sources to back up or explain the approaches taken in the care and management of the patient or to provide possible explanation of some of the author's opinions, findings and conclusions. The authors recommend using Orpet and Jeffery's Ability model 2007 (Figure 1) (Orpet and Welsh, 2011) as a way of helping PCR authors to systematically cover the key nursing issues associated with the veterinary care that should be provided to the patient.

Imposed word limits defined by each journal will be specified and will need to be adhered to. Therefore, it will not always be possible to discuss all aspects of nursing care and authors may have to prioritize their discussion and focus on three or four key nursing issues rather than try to cover everything.

Example of discussion section

The text below provides an example of how the authors have developed one of Orpet and Jeffery's Abilities: Patient's Ability to maintain normal hydration. Please note, fictitious references have been provide for illustrative purposes only.

Small intestinal foreign bodies are a common cause for intestinal surgery in the dog and cat (White et al, 2003; Smith, 2009). Jones (2010) advises that most patients requiring surgical removal of the foreign body are physiologically compromised to some extent with normal fluid and electrolyte balances being disturbed as a result of vomiting, diarrhoea, gas accumulation proximal to the obstruction and the possibility of local or systemic infection and toxaemia (Jones et al, 2004; Smith, 2009). It is essential that the patient is stabilized prior to the surgery with intravenous fluids (Black, 1999; Smith 2009).

The degree of dehydration can be estimated by skin turgor changes. Dehydration above 4% may be noted by an increase in the loss of skin elasticity when pinched into a tent. At 8% dehydration, the tented skin will not return to its normal position and mucus membranes are dry (South, 1999; West, 2009). When the patient presented to the hospital, there was a delay in skin fold return and dry mucus membranes. It was estimated that the patient was at least 6% dehydrated. PCV and TP values of 54% and 85 g/l respectively supported these findings.

Normal fluid maintenance requirements in the dog are estimated between 40–60 ml/kg/day (Smith, 2009; North, 2010). In cases of dehydration it is recommended (East, 2011) that a further replacement amount is added to the maintenance requirement (see appendix III). Based on this formula a total daily fluid replacement of 2750 ml was calculated for this patient.

Conclusion and recommendations for future practice

This section should contain a summary of the main points from the discussion section about how the patient was managed. From this conclusion, authors may wish to identify any areas of the nursing care provided or nursing practice which warrant further discussion or evaluation, or which should or could be done differently in the future. Any wider issues for the veterinary nursing profession or potential areas for future nursing research which have become apparent as a result of nursing this patient or writing up this report may also be included in this section.

References

This section should contain the list of references that were included throughout the PCR. Authors should ascertain from the publisher of the journal to which they are submitting the article the accepted style of referencing (usually the Harvard or Vancouver system) and follow this. Authors should reference work from authoritative primary sources and keep any references to text books to a minimum.

Conclusion

Veterinary nurses intending on writing patient care reports suitable for publication are advised to adopt certain academic conventions for the writing and formatting of their work. In particular, the authors recommend using the Orpet and Jeffery Ability model as a way to structure the discussion and evaluation section of the PCR. By using this patient-focussed nursing model for patient care, it is hoped that authors of PCRs will be encouraged to produce PCRs which focus on a more holistic and patient-focussed approach, thus securing a solid foundation for the future of evidence-based veterinary nursing practice.