Compassion can be defined as an awareness of others' suffering, and the wish to take action to relieve it (Ayl, 2013). Anyone working in the field of caring, whether with animals or people, will be expected to display compassion to those they are providing care for, but the more an individual is compassionate and empathetic to those they are treating, the more vulnerable they are to the effects of compassion fatigue (CF) (Figley, 1995a). The term CF is a relatively modern one that many people are only just becoming familiar with, although the concept of workers being affected by their patients' suffering was first described by the psychiatrist and psychotherapist Carl Jung in 1907. CF was first coined in 1992 when Joinson used it to describe the loss of ability to nurture observed in human nurses working in emergency department settings. CF is now widely recognised in the field of human nursing and has been indicated as a cause of poor job satisfaction, poor job retention and medical errors (Halbesleben et al, 2008).

Veterinary nursing is an evolving profession and it is now commonplace for some animals to be hospitalised for longer periods of time for treatment, meaning registered veterinary nurses (RVNs) may forge close relationships to the patient and their family. Advances in veterinary surgical and medical treatments mean more complex procedures or treatments are now being attempted, and palliative care is more commonplace than before as owners look to extend their pets' lives as much as possible (Downing, 2011). Pet owners now have higher expectations of the medical care provided by veterinary staff (Lovell and Lee, 2013), and heightened emotions may cause them to act irrationally causing communication difficulties, adding to staff stress (Figley and Roop, 2006). The emotionally complex topic of euthanasia is one which the veterinary profession has to deal with, from having end-of-life discussions through to performing euthanasia of an animal. These instances may involve emotionally draining discussions with pet owners, but also in some cases veterinary professionals may have to deal with the moral burden of euthanasing a healthy animal either due to a behavioural issue or over population (Rohlf and Bennett, 2005).

If CF was more widely recognised in the veterinary profession then ideas could be employed from interventions used for human nurses to encourage self care and workplace-based group sessions, hopefully leading to better job satisfaction, staff morale and improved job retention. This should not be confined to veterinary nurses but should cover all employees in the veterinary practice from veterinary surgeons (VSs) through to reception staff, as although their roles may vary each has its individual strains, meaning all may be at risk.

Terminology

There is a wide variation in the terminology used in texts relating to CF, with some terms used interchangeably which may cause confusion even to those familiar with the subject (Figley and Roop, 2006). The term CF is best described as a generic title encompassing subcategories defined by their symptoms and effects (Newell and MacNeil 2010). For the purpose of this study two of the main subcategories of CF were explored; secondary traumatic stress (STS) and burn-out, as these were the subcategories assessed by the chosen method of measure for this research. STS was first described by Figley (1995b) who reported symptoms exactly like those of people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, but in STS the sufferer had only been exposed to the traumatised person, or animal and owner, and had not actually experienced the trauma themselves. Ayl (2013) described it as absorbing the trauma through your eyes and ears. Burnout is typically reactional, caused by work stressors including long working hours, excessive workload and general constraints within the workplace, and is typically slower in onset (Figley, 1995b). Both conditions result in the sufferer feeling frustrated with a low morale, but the burnt-out nurse will gradually withdraw from their responsibilities while the STS nurse will continue to try to give even when it is not in their best interest (McHolm, 2006).

Stamm (2002) recommended when assessing for levels of CF to also assess levels of compassion satisfaction (CS), defined as the reward gained from doing your job well. It was shown that CS was gained from helping others, contributions made to the workplace, a positive relationship with colleagues and the ability to feel you had done your job well. CS was initially hypothesised as a preventative factor against STS by Figley (1995b), however this was superseded by Stamm's 2002 theory that CS will increase an individual's ability to withstand the effects of STS and burnout, but is a protective not preventative effect

Symptoms and risk factors

Symptoms shown by those suffering from STS or burnout vary but may include sleeping disorders, isolation from family and friends, depression, inability to make decisions, irritability and apathy (Pross, 2006); and if signs are ignored may progress to somatic complaints including gastrointestinal disorders, headaches (Boyle, 2011), and a reliance on alcohol to unwind (Hewson, 2014). Although there are many people working in professions who encounter the same experiences not all people are affected in the same way by their work (Boyle, 2011). An individual's current circumstances have a large role to play in their risk of suffering from STS or burnout; caring for young children or elderly parents, divorce and financial concerns may all contribute to how well an individual is able to cope at a particular time. The work environment also plays a large role in an individual's ability to cope, with pressures from paperwork, not feeling valued or being surrounded by negative colleagues all increasing the risk (Mathieu, 2007). Some personality types and traits have also been implicated as more at risk (Sabo, 2011). Individuals who display high levels of optimism and belief that they could control outcomes are considered better at coping with stressful situations and at less risk of CF (Injeyan et al, 2011), therefore autonomous practice by RVNs should be encouraged.

Implications for the profession

The effects of CF will ultimately impact on an individual's work leading to poor attendance, job dissatisfaction and risks to patient safety (Boyle, 2011). Medication errors, poor record keeping and decreased accuracy have been described (Hewson, 2014), and with RVNs now accountable for their actions it is vital that errors are avoided to remove the potential for complaints and disciplinary action. From an employer's perspective, according to Schaufeli (2003), fatigued workers lead to absenteeism, poor productivity and efficiency and ultimately to financial loss. Many people leave their job due to the effects of CF (Rudman and Gustavsson, 2012), and as retention of qualified nursing staff in veterinary practices is an ongoing issue (Snowball, 2012) it is important to address this.

Investigation into the risk of CF in RVNs should be an area of great interest to the whole veterinary profession to ensure animals and their owners get the care that they deserve, that staff remain mentally healthy and the risks of professional error are mini-mised, and that RVNs stay in this rewarding profession. Recognition of CF will allow warning signs to be identified and allow staff to seek help, without the stigma and feeling of isolation experienced by many with mental health issues leading to a delay in them seeking help (Clement et al, 2015).

Professional responsibility

Health and safety legislation dictates that employers have a legal responsibility to minimise risks to their employees, and as well as physical risks they are responsible for minimising stress-related illnesses, which includes ensuring employees' mental wellbeing (D'Souza, 2009). The Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) Codes of Conduct (2012) state that VSs and RVNs have a professional responsibility to address mental health concerns that may impair their own ability to practice, and must take steps if they are concerned about a colleague's mental state which may affect their performance. Workers in the veterinary industry have been identified as being at high risk from CF (Figley, 1995a; MacNair, 2002; Arluke, 2006), and it is vital it is recognised and addressed. In 2014 the RCVS launched ‘Mind Matters’, a mental health wellbeing initiative whose aims include identifying occupational stresses facing those in the veterinary profession (RCVS, 2014), hopefully raising recognition of mental wellbeing in the profession. If CF and its effects are recognised as part of this initiative, employers and employees will be better informed to provide support to individuals who may be experiencing its effect.

Screening for compassion fatigue

When researching the incidence of STS, burnout and CS it is important to use the screening method most suited to that particular investigation and group of people. No single test can assess all aspects of CF, they are designed as a screening test and if an individual is concerned about their results they should speak to a healthcare professional to be properly assessed. All screening methods are deliberately conservative in their stated ranges to avoid the risk of obtaining false negative scores, therefore results for the incidence of CF in a given population may be falsely inflated. The ProQOL survey is the most commonly used measure of CF (Bride et al, 2007). It measures CS, and CF through the use of two subscales of burnout and STS. It is a revised version of the original Compassion Fatigue Self-Test devised by Figley in 1995, which Stamm revised (2010), and is now on its fifth version, and which has demonstrated good reliability across all the subscales (Stamm, 2010). The subscale of CS was added by Stamm in an attempt to highlight the protective effect that the positive effects of caregiving produced against CF (Stamm, 2002).

Methodology

A web-based questionnaire was used as this gave rapid results, was economical while allowing wide geographical coverage, retained anonymity of respondents and allowed easy transfer of data to a spreadsheet for analysis (Denscombe, 2014). Thirty six VN colleges were emailed a link to the online questionnaire to forward on to their user practices and clinical coaches, and an email campaign was sent to a database of 1524 practice email addresses provided by the RCVS, marked for the attention of the VNs. The online link was promoted by the BVNA on their facebook page, on the social media site vetnurse.co.uk, on a weekly email by vetsonline.com and through the researcher's veterinary contacts, to maximise responses to ensure results were representative of the RVN population, as questionnaires are known to produce poor response rates (Cartlidge, 2012). The questionnaire consisted of initial demographic questions followed by the ProQOL survey. A question was included asking for the job title of the respondent, responses received from other personnel including trainee nurses were excluded from the study as this study was chosen to focus specifically on RVNs. The study was targeted at those who had worked within practice for the last 30 days, as the stressors of work could be reduced if the respondent had been absent from work for any period of time. The ProQOL survey used three sub-scales to provide a score for CS, STS and burnout, the results of the three subscales were then analysed to give a guide about the individual's risk of CF. The questions were a mix of positive and negative feelings and emotions; including positive emotions increased the psychometric properties of the scale (Stamm, 2014), and prevented problems which may occur with Likert scale questions, where people duplicate the same score all down the page (Denscombe, 2014).

Results

A total of 992 (n=992) eligible responses were received which, based on March 2014 figures of VNs on the RCVS register (11661), indicated a response rate from RVNs of approximately 8.5%, although some nurses included in the RCVS figures may be employed in other areas such as academia, may have been listed rather than registered, or may not have worked in practice within the last 30 days due to maternity leave, sickness or changing jobs. This response rate was well over the required sample size to give results with a 95% confidence level, with a 5% margin of error (Denscombe, 2014), and therefore was deemed representative of the population of RVNs. 97.5% (967) of the respondents were female and 2.5% (25) male, which reflected RCVS March 2014 figures of approximately 2% of the nursing population being male. 77.8% (772) of the respondents worked full time hours (>35 hours per week).

The majority of the respondents (71.7%; 711) were in the 25–40 year age category, indicating a similar age distribution to RCVS figures of 64% in this age range (RCVS, 2014b).

Just over half of respondents (50.6%; 502) had worked in veterinary practice for over 10 years, 34% (337) had worked in practice for 5–10 years and 15.4% (153) had worked in practice for under 5 years. The majority of respondents (83.4%) (827) worked with small animal +/- exotic species, 15.6% (155) in mixed practices and 1% (10) were working only with equines.

70.5% (699) of respondents worked in first opinion practices, 22.2% (221) in practices doing first opinion and referral work, and 7.3% (72) in practices treating referral only cases. 67.1% (666) of respondents were employed as RVNs, with 27.3% (271) working as head nurses, and 5.5% (55) in other positions in practice. The majority of respondents in the other category were in senior positions although there were some diverse job roles including physiotherapist and hydrotherapist. RVNs working in charity practices represented 10.2% (101) of the respondents, with 8% (79) being dedicated out of hours nurses. 60% (595) of respondents were involved in out of hours or on call work.

Data analysis

Data were imported from the internet survey into an Excel spreadsheet allowing scores to be calculated for each individual following the ProQOL guidelines (see www.proqol.org). Internet-based surveys which can be imported directly onto a spreadsheet eliminate the risk of human error when inputting data manually (Denscombe, 2014). Each of the categories had a minimum possible score of 5, with a maximum possible score of 50. Guidelines for interpretation for each category defined a score of 22 or less as being low, 23–41 as moderate and 42 or more as high (ProQOL 2010) (Table 1).

| Mean | Std. deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Median | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compassion satisfaction | 37.894 | 6.084 | 10 | 50 | 38 |

| Burnout | 28.838 | 4.422 | 16 | 42 | 29 |

| Secondary Trauma | 25.517 | 5.777 | 10 | 44 | 25 |

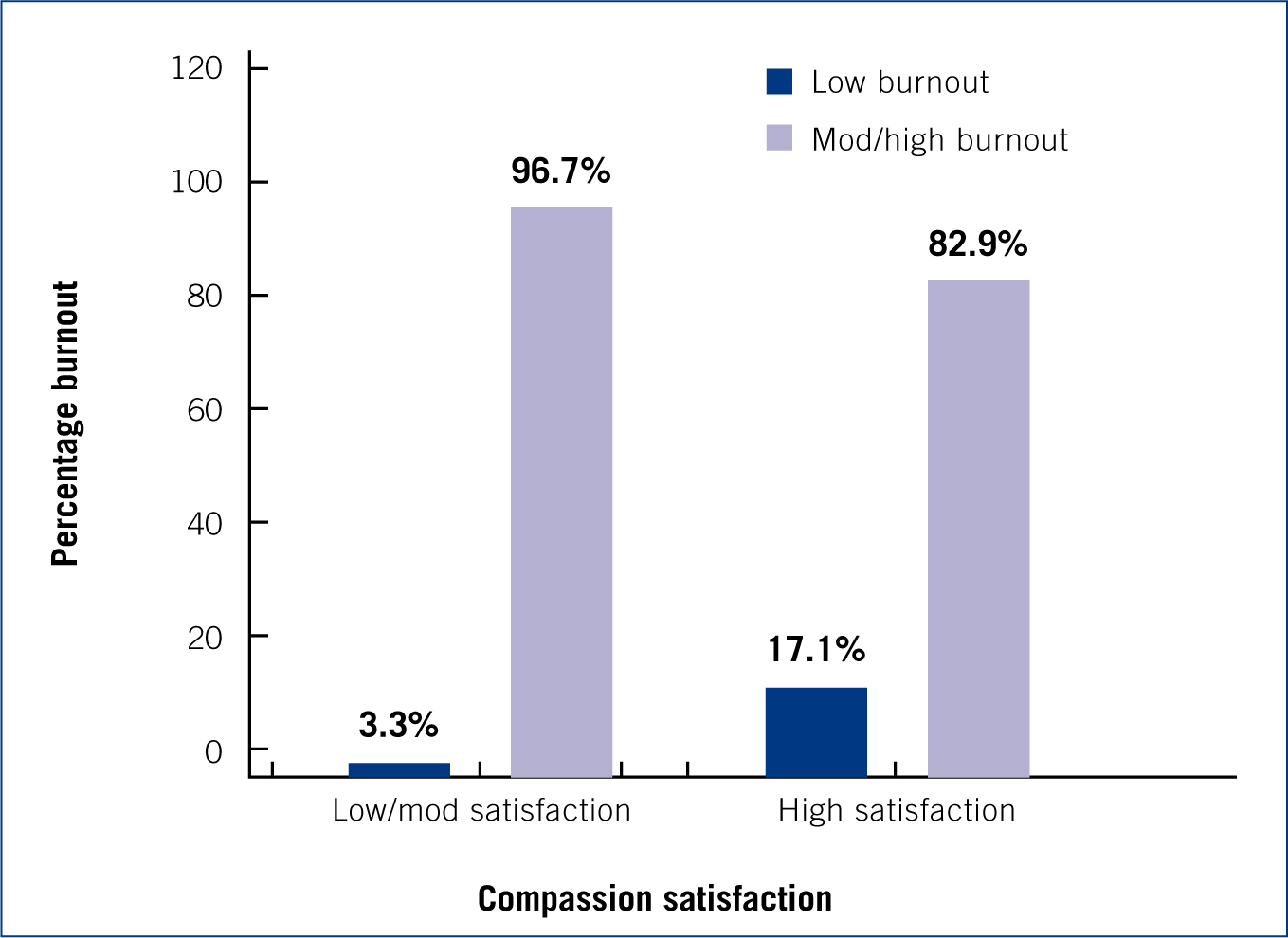

Burnout correlated negatively with CS with 96.7% (682) of those with low levels of CS experiencing moderate to high burnout compared with 82.9% (238) of the RVNs with high levels of CS having moderate/high levels of burnout (p<0.001) (Figure 1).

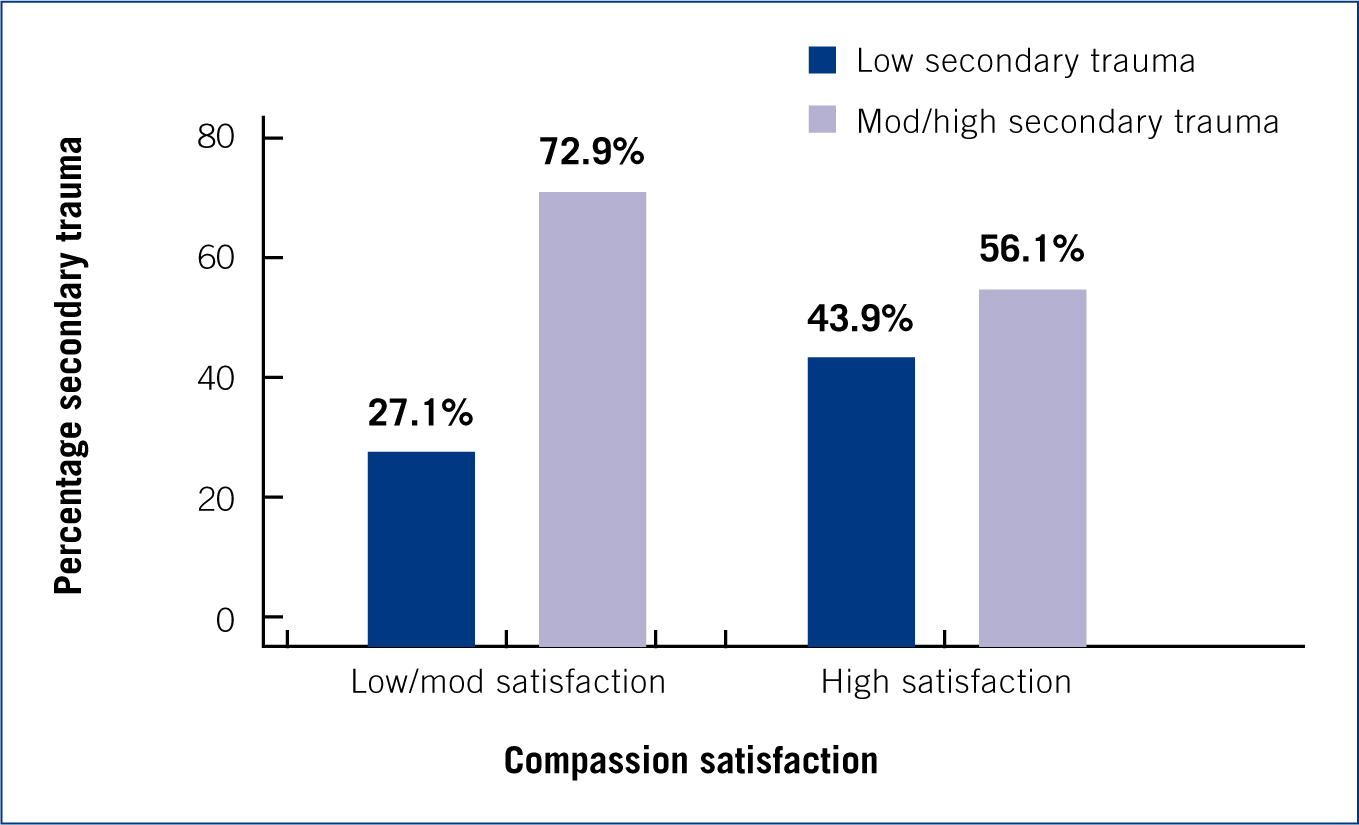

STS correlated negatively with CS, 72.9% (514) of the RVNs with low/moderate levels of CS experienced moderate/high levels of STS compared to 56.1% (161) of the RVNs with high levels of CS (p=<0.001) (Figure 2).

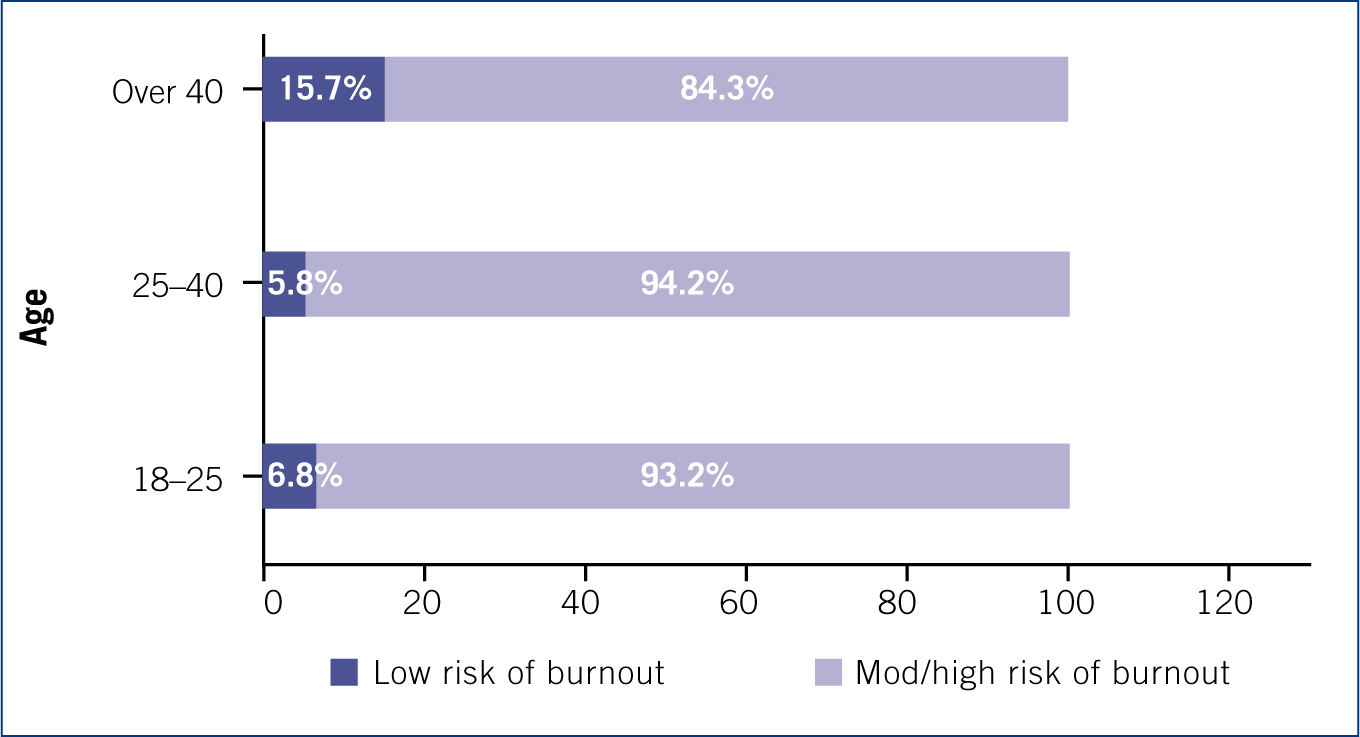

RVNs over the age of 40 displayed a reduced risk of experiencing moderate/high burnout, 84.3% (113), when compared to the other age groups (p=0.001) (Figure 3).

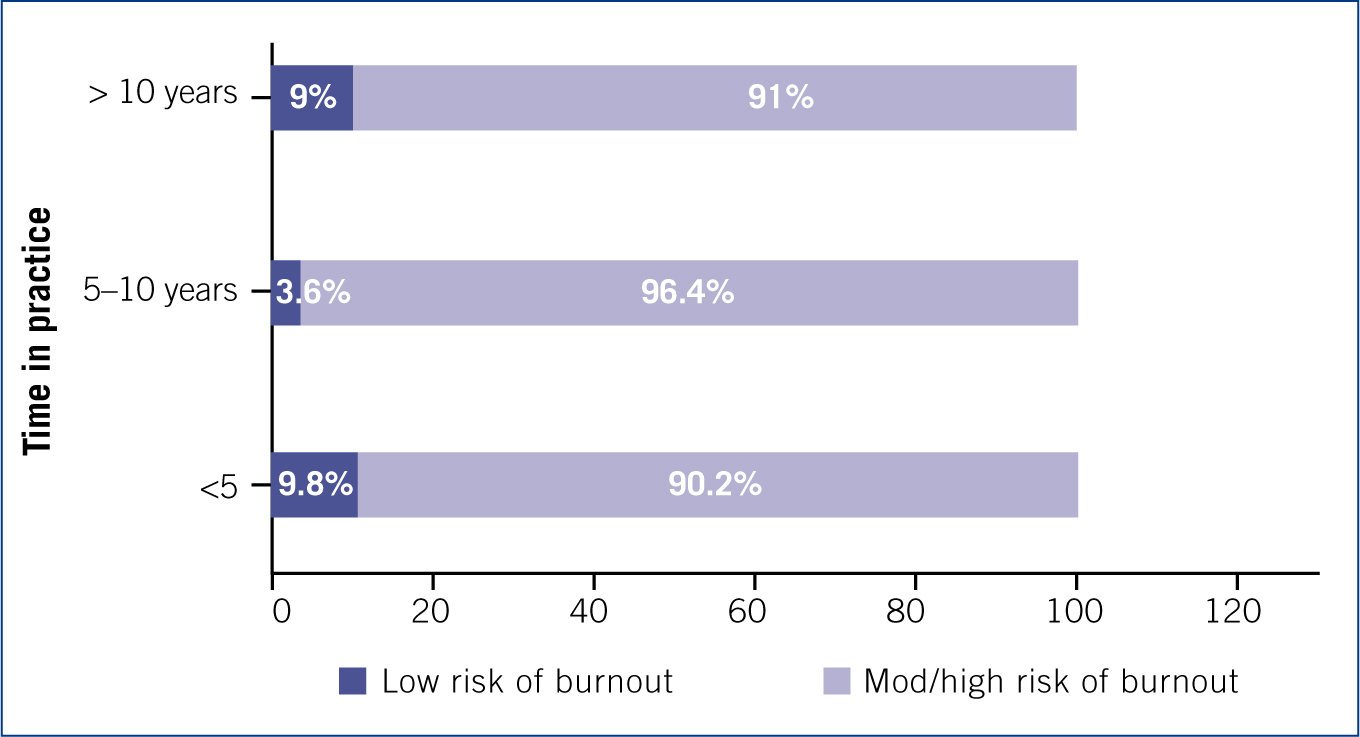

RVNs working in practice for 5–10 years displayed a higher risk of moderate/high burnout, compared with those in practice for under 5 years and over 10 years (p=0.003) (Figure 4).

Dealing with clients appeared to increase the risk of RVNs experiencing STS, with 68.8% (662) of those dealing with clients experiencing a moderate/high risk compared with 43.3% (13) of those not dealing with clients (p=0.005). There was no significant correlation found between involvement in euthanasia, and burnout or STS, although only 3.6% (36) workers were not involved in euthanasia procedures. None of the other variables assessed showed any significant statistical differences when assessing levels of CF, burnout and STS.

When assessing responses to individual questions on the ProQOL survey relating to work-life balance 79.2% (785) of respondents indicated they liked their work as an RVN and 75.7% (751) felt proud of what they do on a regular basis, with 69.2% (686) feeling happy they chose to do this work either often or very often, highlighting the high CS levels found by the study. However, 62.6% (621) of respondents regularly felt worn out because of their work, 37.7% (374) found it difficult to separate their personal life from their life as an RVN on a regular basis and 45% (446) felt overwhelmed due to a never ending workload.

Discussion

Response bias may occur with this type of questionnaire as those feeling stressed may be more likely to reply due to the nature of the survey. Unfortunately there is no way of knowing this, but the good response rate is an encouraging sign, and hopefully signifies an interest in this important issue affecting the profession.

The data collected from this study, and the statistical analysis performed has shown that RVNs are at risk of suffering from STS and burnout as a result of their job, with 68.1% at moderate to high risk of STS, and 92.8% at moderate/high risk of burnout. No statistical correlation was found between working in any particular type of practice including charity or referral practices, job role or performing out of hours duties. The study provided evidence to support the findings of Figley (1995b) and Stamm (2002), that CS does indeed have a protective effect against STS and burn-out, but also that many RVNs are getting satisfaction from doing their job, with only 0.9% exhibiting the lowest levels of CS. Findings have indicated particular risk factors for burnout are those workers under 40 years of age agreeing with the findings of Brewer and Shapard (2004), who indicated this may be due to those who suffer from burnout leaving the profession prior to the age of 40, while those that remain develop skills to cope with the job's demands and emotions based on life experience. Those working in practice for between 5 and 10 years were more at risk of burn-out than those working in practice for <5 or >10 years which may be explained by combining the findings of Dunwoodie and Auret (2007), that burnout increases in healthcare workers remaining in the field for longer than 5 years due to emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation, together with the findings of Brewer and Shapard (2004), that experienced workers remaining in the profession develop coping strategies.

Those dealing with clients were at an increased risk of suffering from STS, supporting the theories of Figley and Roop (2006), Black et al (2011) and Overfield (2014) that dealing with clients is a source of stress, which may be attributed to dealing with clients in an emotional state regarding their pets, and sometimes listening to them reliving distressing events. No correlation was found to support previous theories that euthanasia may contribute to burnout or STS (Rohlf and Bennett, 2005; Arluke 2006), although the number of respondents not dealing with euthanasia in this study was very limited, and the amount of euthanasia situations encountered by individuals was also not assessed.

The individual answers to questions relating to work-life balance support the findings of Overfield (2014) and Foster and Maples (2014), and demonstrate the risk to work-life balance for those working in the profession, which Kimber (2014) highlighted as being an important factor in the prevention of burnout.

Recommendations for the profession

The confirmation that working as an RVN puts workers at high risk of suffering from STS and burn-out highlights the need for more awareness of these conditions in veterinary practice. The RCVS Codes of Conduct (2012) oblige veterinary nurses to be aware of their own and their colleagues' mental wellbeing, and employers have a duty of care to protect their employees mental health, so by educating workers of the signs of these conditions more may be done to recognise the warning signs so they may seek help. The RCVS Mind Matters initiative (2014) is highlighting the mental wellbeing of veterinary professionals, and along with the RCVS Health Protocol (2013) aims to provide more support, including for those who may be subject to complaints or disciplinary action as a result of mental health issues. As part of this initiative, awareness of CF, its symptoms and effects, and the interventions which may reduce the risk to workers, should be promoted to the veterinary profession through articles in veterinary publications and at veterinary congresses, to enable mental health issues to lose their taboo status, so they are no longer something to be ashamed of. The protective effect of CS (Stamm, 2002) is one which employers should nurture, ensuring workers feel valued and worthwhile in their role by offering praise, encouraging autonomy, and ensuring the provision of a positive work environment with supportive colleagues. A good work-life balance should be encouraged with the provision for adequate rest time, and the use of proven interventions should be considered such as debriefing sessions and access to support groups (Boyle, 2011). The provision of experienced nurses acting as emotional mentors for newly qualified nurses could be considered (Erickson and Grove, 2008) as the sudden loss of the support and guidance provided by a clinical coach on qualification may lead to a feeling of vulnerability. Part of the responsibility must remain with the individual to practice self-care including a healthy diet, sufficient exercise and relaxation, and to seek help if they feel they need it (Hewson, 2014). Research has highlighted that dealing with clients may cause higher levels of STS in RVNs therefore training staff in effective communication and grief counselling skills may assist them when coping with stressful situations, and regular CPD will ensure that staff feel worthwhile and empowered in their role. If particular staff members are struggling with stress employers should offer to send them on specific training courses to help them manage their workload and stress levels more effectively. Screening tests could be introduced to detect the risk of CF or stress in staff members, while in a small practice retaining confidentiality could be challenging, in larger group practices they may give a generic indicator of staff wellbeing and satisfaction levels.

Conclusion

The findings of this initial survey shows that UK practising RVNs are at risk of CF. Improving awareness of the risks of CF will hopefully encourage nurses to ensure they retain a good work-life balance, and provide support for their colleagues when needed. Employers should strive to ensure staff feel appreciated in their roles to encourage high levels of CS, and should recognise the importance of a mentally healthy work-force.