Diagnosis of parasitic infections in animals is an exciting and stimulating challenge. There are several ways to diagnose parasitic infections: by direct identification of the parasite, by serology or using molecular methods.

To perform direct identification of parasites, particularly ova present in faeces, it is possible to use faecal smears, flotation and sedimentation tests. Morphology and dimensions are the major diagnostic criteria to which a microscope is key in the veterinary clinic. The faecal flotation of parasitic forms enables confirmation of these criteria and is therefore routinely used for the detection of most parasites residing within the gastrointestinal tract (Foreyt, 1989). Methods based on flotation are fast and inexpensive, and can be quickly implemented as a measure for infection control (Sousa et al, 2016). Despite these advantages, there are also some limitations in these methods:

The Willis method (Willis, 1921) is a flotation method, used for detection of light structures such as protozoan cysts and light helminth eggs (Carvalho et al, 2012; Sousa et al, 2016). This assay has been the most commonly used technique for detecting these parasitic structures (Cerqueira et al, 2007). It was nearly a century ago, in 1921 that H. Hastings Willis first published an improved method to reliably detect hookworm ova, providing a significantly higher percentage of positive results than the previously used smear and centrifuge methods (or their combination) (Willis, 1921). The Willis method, published in the reputable Medical Journal of Australia, was based on two wellknown assumptions: that the eggs float in a salt solution of approximately 1.130 specific gravity; and adhere to a glass surface with which they come into contact. This last property of egg adhesion was described in 1908 by William Pepper, an Assistant Professor of Clinical Pathology, University of Pennsylvania. Pepper had recently treated two cases of uncinariasis (Uncinaria duodenale and Uncinaria americana), and while making frequent examinations of the patient's stools, Pepper noted that the parasites' ova were quite sticky and that this peculiarity could be made use of in searching for them. In particular, Pepper proposed that a drop of the washed sedimented faeces be allowed to stand on a slide for a few minutes and then immersed in water and examined microscopically, after which only the eggs would be found adhering to the slide, and all other material would have washed away. Willis, taking into consideration Peppers findings, used a container measuring 3.3 cm in diameter and 0.8 cm in height; filled about one-sixth with stools to be examined, and the rest with salt solution to which stools were thoroughly mixed. The final step focused on filling the solution to the brim to which, after a few minutes, a glass slide was placed in contact with the surface of the liquid, allowed to remain a short time, and then placed under the microscope. Since its first description, the Willis method has been suggested with many minor adaptations.

The Willis method is a qualitative method and it is very useful to use in preliminary surveys, in order to establish which parasite groups are present in the faecal sample. With this method, eggs are separated from faecal material and concentrated by a flotation fluid (p.e NaCl, sugar) of an appropriate specific gravity.

Sample

Before discussing the method, it is important to consider the sample. Ideally, faecal examinations should be conducted on fresh faecal material. If faecal samples are analysed (or submitted to the laboratory) after being in the environment for hours or days, it is possible that some fragile parasites may die and disappear. In addition to this, nematode eggs can hatch within a few days, and larvae are more difficult to identify than eggs. Another disadvantage of using faecal samples from the ground, is the possibility that they may be invaded by free-living nematodes, hindering parasite identification (Sloss et al, 1994; Knottenbelt, 2007). Owners of small animals should be instructed to collect several grams of faeces, immediately after defecation (Sloss et al, 1994). It is also possible to collect samples directly from the rectum. In small animals in particular, this procedure should be executed with caution, to prevent any discomfort to the animal. It is important to wear gloves and lubricate a gloved finger, then insert the finger slowly and gently into the rectum. If there is a limited amount of faeces recovered, negative results should be cautiously interpreted, since there are many infestations that produce only small numbers of eggs, and so may go unnoticed. When dealing with livestock this procedure is easier to execute, and there is no concern regarding the amount of faeces obtained. But, due to the fact that egg liberation is not constant over time, even with large faecal volumes false negative results may occur. One way to minimise these (eventual) false negative results is to collect and process not only a single sample, but several samples on different consecutive days, to improve sensitivity.

The Willis method

Equipment needed:

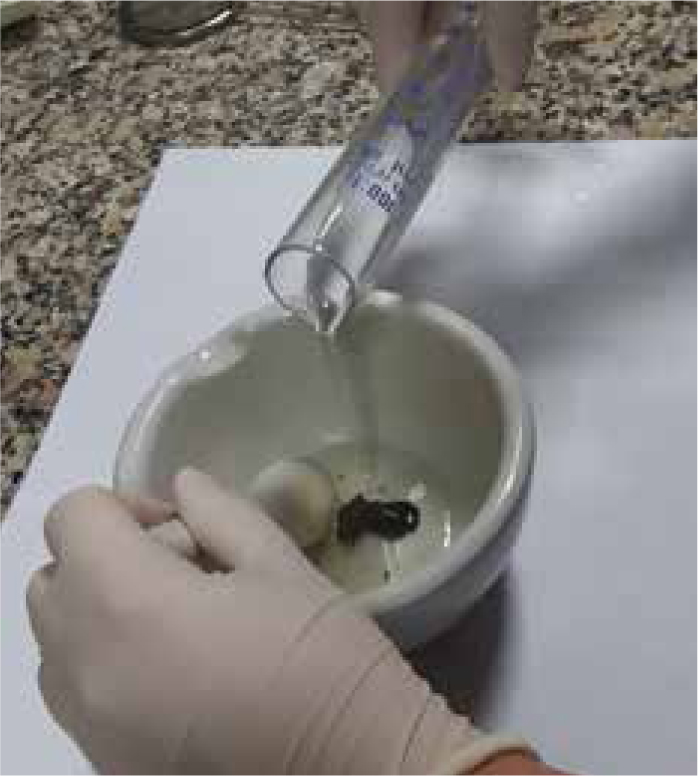

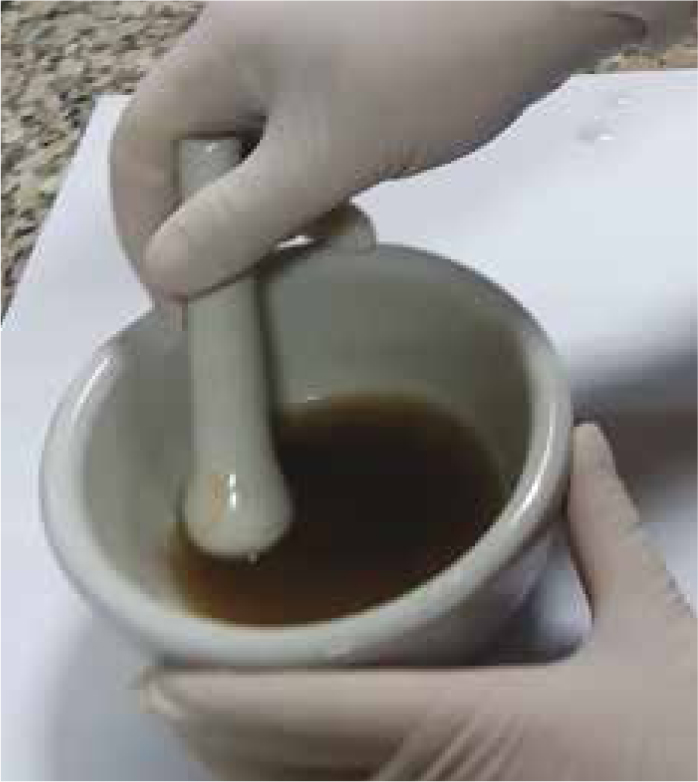

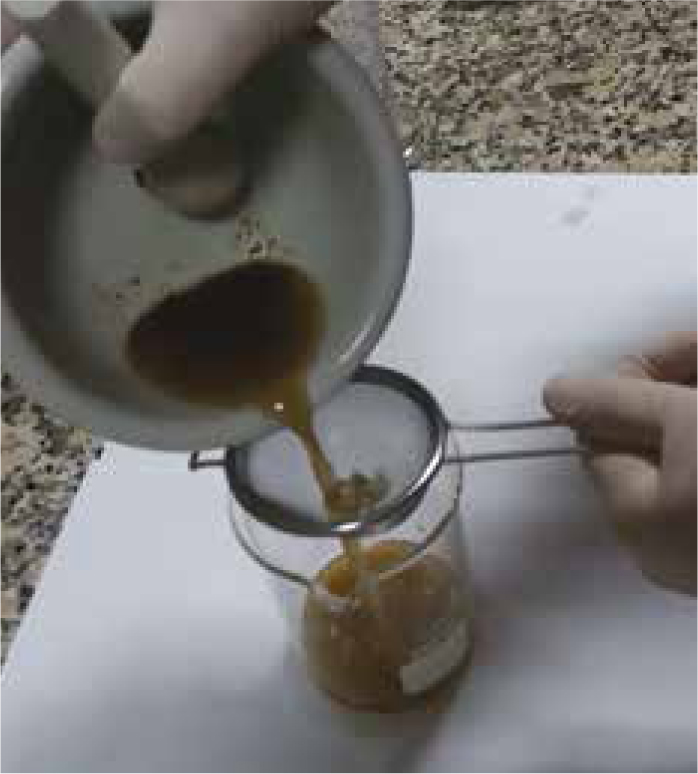

Step-by-step guide

Further considerations

There are commercial faecal floatation kits that provide a flotation solution (sodium nitrate solution) and a container for collecting the sample and running the test. Some practitioners may find these kits more convenient than the in-house procedure.

The Willis method is an easy one to perform and it requires inexpensive equipment that can easily be found in the practice (for instance, replace teaspoon with forks, tongue blades or stirring rod; tea strainer with double layer cheesecloth, beaker with plastic containers etc). Veterinary nurses have an important role to play in performing parasitological procedures. They are able to prepare solutions and perform coprological tests, and also to identify common adult parasites and their ova. Likewise, the VN should have knowledge of common parasite life cycles (nematodes; trematodes; cestodes; protozoa).

To end this first article on ABC parasitologic series, it is important to highlight that faeces are biologic material and that some faecal pathogens and faecal parasites are zoonotic (Knottenbelt, 2007). Faeces, (and urine, aspirates, swabs etc) should always be presumed to be infectious. It is of the utmost importance to wear protective outerwear and disposable gloves when handling it. Discarding gloves and washing hands before touching clean items (e.g. microscopes, telephones, food) is also imperative. Eating and drinking should not be allowed when performing these tests. Health and safety regulations should always be followed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, to identify parasites and particularly ova, one can easily execute the procedure here described — the Willis faecal flotation method — by using inexpensive everyday laboratory equipment and by performing a fast and simple method that can be used for infection control.