Horse racing is a multimillion pound industry in Britain attracting over 6 million spectators per year (British Horse Industry Confederation, 2010) and contributing £3.7 billion to the economy (British Horse Racing Authority, 2011). The pinnacle of the National Hunt racing season in Britain and Ireland is the Cheltenham Festival, a 4-day race meeting incorporating hurdle and steeplechase races. Each race at the Festival is a test of the most highly rated jump horses of that season. Its origins date back to the early 1800s when organised horse races were reported at Nottingham Hill, Cheltenham. Racing moved to its current home of Prestbury Park in 1831, with the first Festival recorded in 1902. The 1904 meeting featured a 4 mile steeplechase, the National Hunt Chase, which evolved into the inaugural Gold Cup in 1924. The Gold Cup is widely acknowledged as the most prestigious honour and the ‘blue riband’ of jump racing, and is currently the most valuable non-handicap jump race in Britain with total prize money of £475 000 offered in 2010. The modern race has been run on the left handed ‘New Course’ at Cheltenham since 1959, and comprises a 3 mile 2½ furlong (5331 metre) Grade 1 steeplechase incorporating 22 jumping efforts.

The Festival, and particularly the Gold Cup, captures the attention of the general public and the winner has the potential to become a household name joining the illustrious company of Golden Miller, Arkle, Dawn Run, Best Mate and Kauto Star. Industry and public plaudits also await the winning trainer and jockey. The Festival celebrated its centenary in 2011 and continues to gain in popularity, and provides a significant financial contribution to the racing industry and local economy.

The thoroughbred racing industry values blood-lines and breeding as the fundamental core of success; 95% of modern racehorse parental lineages are descended from one sire and 72% from 10 foundation mares resulting in a limited population with multiple incidences of in-breeding (Thiruvenkadan et al. 2009). The racing industry records quantitative data relating to performance variables and this has been used to assess heritability of racing performance (Mota et al. 2005; Thiruvenkadan et al. 2009). These heritability estimates indicate that between 16 to 96% of the variability in performance may be due to genetic factors. Performance parameters available for analysis include pedigree, race time, speed, distance and career record but the influence of extrinsic variables, for example trainer, jockey, track and going, could prohibit a broad brush approach to predicting success in individual performance tests and may explain the low heritability values recorded for competition success.

Epidemiological techniques have traditionally been used to analyse disease, but have also been utilised within racing to identify risk factors associated with falling and injury (Williams et al. 2001; Stover, 2003; Parkin et al, 2007). Marlin et al (2010) were the first to the authors' knowledge to use epidemiology to evaluate factors that could predict individual performance in a specific horse race, the Epsom Derby the ‘blue riband’ event of British flat racing. This work identified that horses which were foaled in Ireland (odds ratio (OR) = 1.49; p=0.018), had won 2 year old races (OR= 2.54; p=0.041) and had one consistent jockey for their career (OR=2.88; p=0.022) prior to the race increased the probability of their success. The predictive probability of a win for each potential covariate pattern in the final model was applied to the 2010 Derby field. This analysis identified ‘At First Sight’ as a horse that had much higher betting odds (150-1) than predicted by the model. This horse eventually finished 2nd in the race even though he started the race as a 150:1 outsider. The purpose of the present study was to apply the principles of epidemiology to predict individual performance in The Gold Cup and strengthen the potential of epidemiology as a valid methodology for predicting racehorse performance.

Materials and methods

Factors that could influence racehorse performance were recorded for 15 runnings of the Cheltenham Gold Cup, between 1995 and 2010, the race was cancelled in 2001 due to foot and mouth disease; data were collected using The Racing Post website (www.racingpost.com.). For each runner sire, dam, dam and sire grand-sire, dam and sire grand-dam, country foaled in, foal number from dam, age (years) at time of the race and their colour was identified. The racing career history of each horse was analysed to identify: number of runs; runs on a left handed or right handed track; runs at Cheltenham; total number of races won and failed to complete with respect to flat, hurdle, bumpers, point-to-point and steeplechase races and wins at Cheltenham; and the trainer at the time of race, total number of trainers in career; jockey at time of race and total number of jockeys in career. Betting odds at the start of the race and the ground conditions (going) were also noted. Sex and weight carried were discounted as significant variables as only one mare competed during the period examined and because weight carried in the Gold Cup was consistent from 1995 to 2003 for all geldings (12 stone) and from 2004 to 2010 (weight was decreased to 11 stone 10 lbs). All variables recorded were tested as random effects that could influence final placing within the Gold Cup.

Statistical analysis

Univariate and multivariable single-level and mixed effects logistic regression models were developed using winning the Cheltenham Gold Cup as the dependent variable. Several variables such as sire, dam, sire grand-sire, sire grand-dam, dam grand-sire, dam grand-dam, trainer, training location and breeder were included as random effects to assess for clustering at these levels. However, none of these random effects were significant. All fixed effects variables with a p-value of ≤0.25 during the univariate screening process were available for inclusion in the final multivariable model. Mixed effects multivariable logistic regression models were developed, using a forward selection procedure. Variables with strong a priori biological reasons for inclusion were also considered in the final model and biologically plausible interaction terms were investigated. Variables were retained in the final model if they were present at a significant level (p<0.05).

Results

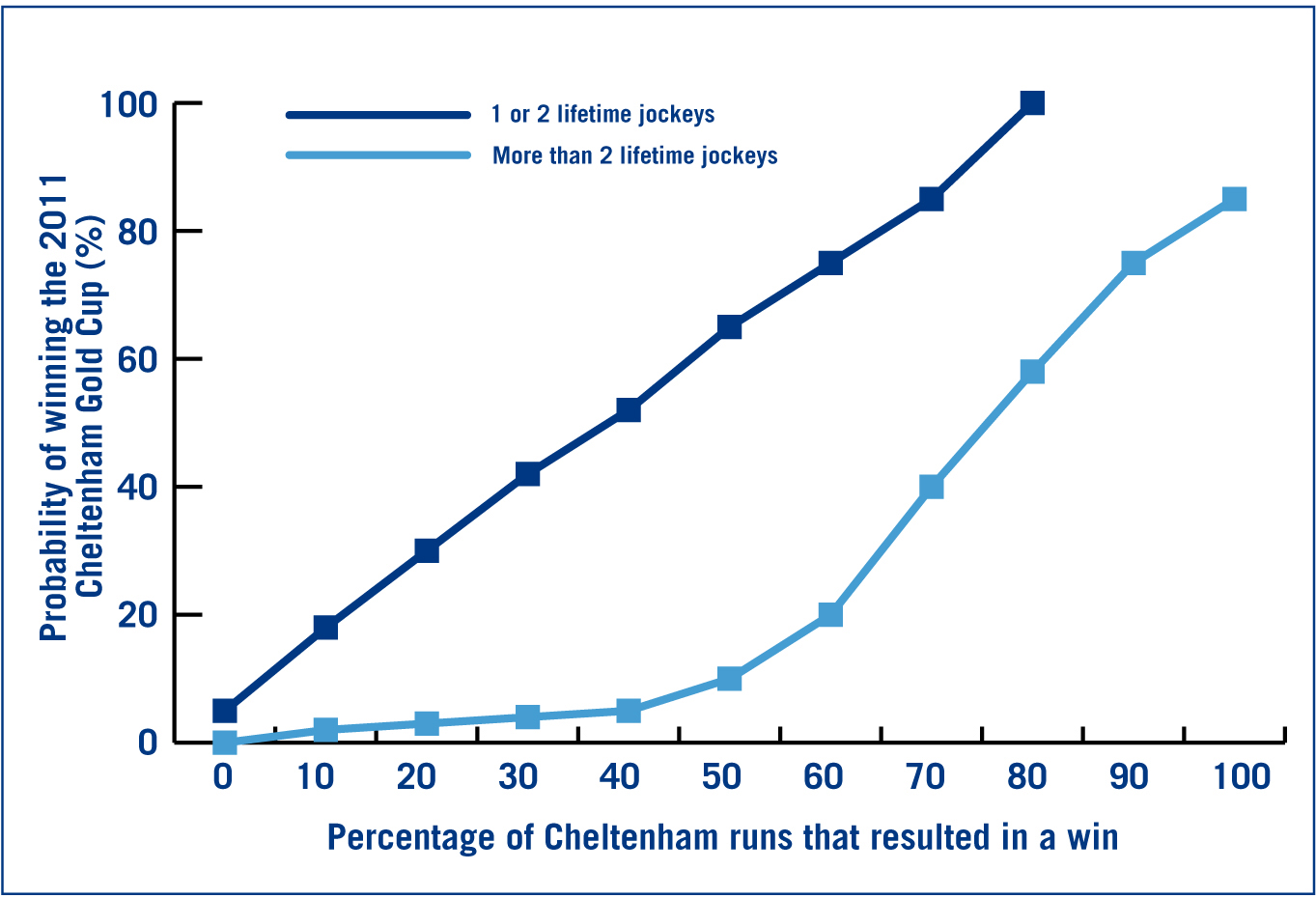

Between 1995 and 2010 in 15 runnings of the Cheltenham Gold Cup, a total of 217 horses started the race. The probability of an individual horse winning the Gold Cup is 0.065. Table 1 shows that over the past 15 years, the variables that were related to an increased chance of success in the Gold Cup (in the final multivariable logistic regression model) were the number of race starts at Cheltenham that resulted in a winning performance and having the same jockey or a maximum of two jockeys in all races throughout the horse's career up to and including the Gold Cup.

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of starts at Cheltenham that resulted in a win (deciles) | 1.09 | 1.05-1.13 | <0.001 |

| Number of jockeys during career to date: | |||

| Three or more (reference category) | 1 | ||

| One or two | 33.9 | 2.47-467.42 | 0.008 |

For each extra 10 percentage point increase in the percentage of starts at Cheltenham that resulted in a win, the odds of winning the Gold Cup increased by 1.09 times. Horses that had been ridden by only one or two jockeys throughout their career were 40 times more likely to win the Gold Cup than horses that had been ridden by three or more jockeys.

Figure 1 provides an example of how the final model can be applied; here the probability of a win for a horse that had been ridden by more than two lifetime jockeys and had won 70% of its Cheltenham starts is shown as 42%. However the confidence interval (CI) is relatively wide (probability of winning 95% CI =27- 57%) therefore some caution should be applied in the final interpretation of the model.

Discussion

Influence of win percentage from careers starts at Cheltenham racecourse

Traditionally within the racing industry, the adage ‘horses for courses’ is commonly applied when predicting race performance and respective course specialists are often rated at lower odds in the betting market. Therefore perhaps it should not be surprising that the percentage of starts won by a horse at Cheltenham racecourse is significantly associated with an improved chance of winning the Gold Cup. The Cheltenham New Course is described as a stiff, left handed, highly undulating galloping track and comprises a 1 mile 5 furlong oval course with a unique 220 yard run in on an uphill gradient of 10 (Racingpost, 2011). Right and left-handed National Hunt racecourses exist in Britain and Ireland, and these exhibit variable circumferences between 1 mile and 2 mile 2 furlongs. Trainers will consider the orientation of a course when selecting races for horses under their charge; repeated left-handed performances could facilitate musculoskeletal adaptation and learned behaviour in individuals which could compound exhibition of a lateral preference. Laterality has been investigated in thoroughbreds; Williams and Norris (2007) investigated laterality bias within gallop stride patterns in thoroughbred race-horses and found 90% exhibited a right lead preference and 10% a left lead preference at the start, during gallop work and within racing performances. It could be concluded that individuals that possess an inherent left canter lead bias would exhibit superior performance at Cheltenham and other left-handed racecourses, but this does not explain the significance of an increased win:number of starts ratio in predicting performance.

Another possible explanation for the success of course specialists could be linked to the unique physical test that races at Cheltenham, particularly over the New Course, present. Horses which succeed at this racetrack have to show progression on the inclining and extra long run in to the finishing post as well as navigate both uphill and downhill jumping efforts. Fitness and conformation could be proposed to be instrumental in addition to laterality in achieving and winning. Horses could exhibit a physiological profile that facilitates a prolonged superior performance over the acknowledged testing track. Interestingly the second significant variable (career number of jockeys) could influence the physiological performance of their mount, as a skilled jockey will ride their horse's optimal race, using their judgement to maximise their horse's performance. It could be postulated that some individual horses may be ‘designed’ to be superior performers therefore the elite test that Cheltenham presents, allows these individuals to demonstrate their exceptional ability. That the Cheltenham Festival is considered the pinnacle of the National Hunt season supports this view.

Influence of a consistent jockey-horse partnership

In a consistent partnership the jockey would be expected to ‘know’ the horse well and may have ridden it previously at Cheltenham so should be equipped to maximise performance and facilitate success. Interestingly horses which have recorded multiple wins in the Gold Cup, with the exception of the most successful Golden Miller (5 wins; 3 jockeys), have done so with the same jockey for example Cottage Rake (3 wins), Arkle (3 wins), L'Escargot (2 wins) Best Mate (3 wins) and Kauto Star (2 wins). Although it should be noted that in this study it is the consistency of a career partnership which is significant not the presence of a particular jockey. Within ridden jumping the presence of the rider and the environment may exert a disruptive influence on the linear and temporal biomechanics of jumping; a consistent partnership should reduce any negative impact.

The importance of coach and mentor relationships has been well documented in sporting, educational and business fields (Jowett and Cockerill, 2003; Ely et al. 2006; Carraher et al. 2008). Mentoring is defined as a dyadic interrelationship between a less experienced individual (the protégé) and a more experienced individual (the mentor) with the long-term goal being to promote the development of performance (Ely et al. 2006). Carraher et al (2008) found that individuals mentored by high ranking or successful mentors emulate the trends observed in their peers, therefore it could be theorised that a horse engaged with a consistent jockey would produce performance traits shaped via their influence. The Festival is acknowledged as an elite test of equine performance and as such many of the human participants are already established as field leaders. Top trainers retain top jockeys and attract future top horses, and therefore equine athletes who exhibit potential and are in training in these environments, may engage with an elite jockey partnership throughout their career thus promoting superior performance.

The athlete-coach relationship is considered instrumental to successful performance in sports even at elite levels (Jowett et al. 2003) and the development of a consistent, close relationship while it facilitates a high degree of interaction also promotes inter-reliance within the parties involved (Lorimer and Jowett, 2009). The resultant complex relationship will impact on the efficiency of performance. The athlete (horse) has a requirement to acquire knowledge and skills from the coach/ mentor (jockey) to achieve success. Reinforcement via repetition within the performance environment (previous races) will enhance the partnership and promote the notion of mutual understanding or knowing what makes them tick (Lorimer and Jowett, 2009) and could explain the significance observed. The evidence presented in this study also supports previous work (Marlin et al. 2010) and suggests that development of consistent dyadic relationships between the horse and rider in racing enhance equine performance. This has value to be investigated in other equestrian disciplines. However, it is also possible that this association is a proxy measure of other training-related factors. For example, top-class trainers are more likely to ‘retain’ top class jockeys thus reducing the likely number of different jockeys that a horse from one of these trainers would have during its career. It may be that this apparent jockey-related factor is therefore a proxy measure of training facilities or regimens employed by the better trainers and it is these (unmeasured in this study) training-related factors that are associated with success in the Cheltenham Gold Cup.

Non-significant factors

Surprisingly, both the specific trainer and the number of career trainers a horse had prior to the race were not linked to performance in this study. The jockey could be considered a direct link to the horse in contrast to the trainer who exerts an indirect influence on the equine athlete's performance. Future work to explore the power of dyadic (jockey- horse and horse-trainer) and triadic (jockey-horse- trainer) relationships and their influence on performance is warranted. It is also worthy of note that breeding was not found to exert a predictive value on the outcome of the Gold Cup, a finding which mimics that found when evaluating predictive factors of performance in the Epsom Derby. Thiruvenkadan et al (2009) reported low heritability estimates for racing performance and this may explain the apparent lack of any association between bloodlines and success.

Limitations of the study

A caveat should be applied to the application of epidemiological methods to predict performance in National Hunt racing as there will always be an increased element of chance in jump racing due to the presence of obstacles and the influence of other runners particularly during jumping. The Gold Cup, unlike many other jump races, has a pre-race parade which could excite horses, while horses may also be carrying subclinical pathology which may negatively influence their performance. All of these factors can unfortunately not be incorporated into predictive analysis. Trainers may also enter multiple runners one of which could act as a pacemaker for its stable mate and could weaken the analysis; however it should be noted that At First Sight (2nd in the 2010 Epsom Derby) was such a horse and performed well corresponding to predictive factors employed and in contrast to the form book.

Conclusion

Epidemiology appears to be a valid tool for predicting variables that can increase the probability of superior performance for specific events and has potential to be utilised in other sporting fields. Horses entering the Cheltenham Gold Cup who have had one or two consistent jockeys throughout their racing career and/or have a high win ratio per number of starts at Cheltenham are predicted to perform superiorly to their peers who do not.