Burnout, compassion fatigue and moral distress are prevalent in healthcare professions, yet there is limited evidence specifically relating to veterinary professionals (Gustavsson et al, 2010; Lamiani et al, 2017; Dev et al, 2018). Research highlights the prevalence of burnout and compassion fatigue in veterinary surgeons and veterinary students (Hansez et al, 2008; Reijula et al, 2003; Chigerwe et al, 2014; Mastenbroek et al, 2014; McArthur et al, 2017), but there is limited research regarding burnout in registered veterinary nurses, veterinary technicians and Australian veterinary nurses (Smith, 2016; Kogan et al, 2020; Beetham et al, 2020). Notably, Smith (2016) is the only UK-specific study of burnout and compassion fatigue in registered veterinary nurses and there are clear gaps within veterinary research exploring these conditions among patient care assistants and veterinary receptionists. Primary research among veterinary professionals regarding the prevalence and contributing factors of moral distress is extremely limited; and because veterinary professionals are involved in ethical dilemmas which other health professionals may not be exposed to, further research is required.

Literature review

Burnout

Burnout is widely recognised and researched in human medical professionals (Gustavsson et al, 2010; Dev et al, 2018), yet relatively newly explored within veterinary research. The first recognised instrument to measure burnout was developed by Maslach (1999). The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) identified three characteristics of burnout: emotional exhaustion, detached response to other people or depersonalisation, and lack of personal accomplishment.

Reijula et al (2003) first explored burnout in veterinary surgeons working in Finland and found that 40% of the 775 participants had moderate burnout symptoms and 1.7% had severe symptoms. Notably, there were clear differences in the prevalence of work-related burnout in veterinary surgeons depending on the type of work. Private practitioners experienced the least burnout (serious 2.4% and moderate 30.5%), followed by veterinary surgeons working for corporate companies (serious 1.3% and moderate 37%). The highest prevalence of burnout was seen among veterinary surgeons working for the state (veterinary surgeons with governmental duties; serious exhaustion 2.8% and moderate exhaustion 49%). Of the three different dimensions of burnout, the participants scored highest on the emotional exhaustion dimension; the most common causes of stress according to the assigned duties were being on-call, administrative duties, and insecurity of the work contract.

Hansez et al (2008) found that 15% of Belgian veterinary surgeons were suffering from high burnout, with differing results between different job roles. Bovine and mixed practice veterinary surgeons were particularly at risk, because of the unpredictability of the working schedule and on-call duty.

Chigerwe et al (2014) explored burnout in veterinary students using a variant of the MBI instrument including an Educator Survey (MBI-ES); a version of the MBI for use with educators including teachers, administrators, staff members and volunteers working in an educational setting. The study found the MBI-ES practical to use longitudinally (twice per year). The study revealed that veterinary students had the greatest levels of emotional exhaustion in the spring semester compared to the fall semester, while scores for depersonalisation and personal accomplishment were not different between the fall and spring semesters. The study showed that veterinary students experienced symptoms of burnout throughout their training (Chigerwe et al, 2014). Chigerwe et al (2014) highlighted that the main contributing factor appeared to be related to living arrangements; veterinary students living with another student had lower levels of burnout, indicating that a support system could reduce stress and likelihood of burnout. Emotional exhaustion scores were higher in the spring semester compared to the fall semester, likely because of an increased workload. This highlights that all types of veterinary students could be at risk of burnout early in their careers.

Mastenbroek et al (2014) studied the influence of gender on burnout and engagement in young veterinary professionals. They used a number of tools within a self-report questionnaire including a short version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES), the MBI-General Survey (MBI-GS) and the Veterinary Demands and Resources Questionnaire (Vet-DRQ). This allowed the researchers to explore burnout, and other factors including work engagement, job demands and job/personal resources. Male veterinary surgeons were less exhausted and more engaged than female veterinary surgeons; job demands such as work-home interference and workload correlated with exhaustion. The prevalence of burnout among veterinary professionals was 14% within the first 10 years after graduation. Female participants within their first 5 years of graduation had higher levels of burnout (18%). Mastenbroek et al (2014) highlighted that veterinary graduates were less exhausted, less cynical but also less engaged than the control group (a random sample of the Dutch working population). Although the results were not in line with the expectation that young veterinary professionals are more at risk of burnout, the study highlights the prevalence of burnout among veterinary professionals within the first 10 years after graduation.

Smith (2016) specifically explored burnout and compassion fatigue in registered veterinary nurses in the UK. The data were collected via a questionnaire which used the Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQol) instrument for measuring burnout and compassion fatigue. Of the 992 respondents, 92% were identified as being at moderate or high risk of burnout. Similarly, Kogan et al (2020) used the MBI-GS and the Stanford Professional Fulfilment Index (PFI) to explore burnout in veterinary technicians in the USA and Canada. The PFI is a validated survey designed for physicians that measures professional fulfilment and burnout. Similar to Smith’s (2016) study, Kogan et al (2020) found that veterinary technicians were experiencing high levels of burnout and identified key components as work time, length of shifts, lack of recognition and utilisation of staff. Survey participants reported high levels of burnout across all three dimensions of the MBI; the high PFI scores on work exhaustion, interpersonal engagement and low professional fulfilment verified these results.

Beetham et al (2021) studied levels of burnout among veterinary nurses in New Zealand during the CO VID-19 pandemic. They distributed an online survey which used the ProQoL scale, and received 166 usable responses. The mean score of 28 for burnout indicated that participants were at moderate risk of burnout. The participants were found to have coped exceptionally well during the pandemic, but the results highlighted that the issues were present pre-pandemic.

There is currently no research specifically investigating burnout in veterinary receptionists or patient care assistants, although Scotney et al (2019) investigated animalbased jobs including the sub-category of veterinary nurses, animal technicians and receptionists. They noted that veterinary surgeons showed the greatest risk of burnout, with 80% of respondents reporting moderate to high levels and veterinary nurses showed similar results, with 75% of respondents reporting moderate to high levels. Further specific research is required for veterinary receptionists and patient care assistants as these jobs can differ considerably from those within the ‘other’ category.

Compassion fatigue

ProQoL is a validated instrument for measuring compassion fatigue in professional occupations (Stamm, 2010), but few veterinary nursing studies have explored compassion fatigue using this instrument. The ProQoL is a self-reporting survey which produces scores for compassion satisfaction, burnout and compassion fatigue, which can be classified as either low (scores <23), moderate (between 23 and 41) or high (scores >41) (Stamm, 2010).

Smith (2016) used the ProQoL instrument within an online questionnaire and found that 68.1% of the 992 participants had moderate or high risk of compassion fatigue. No statistical correlation was found between working in any particular type of practice, including charity or referral practices, job role or performing out-of-hours duties (Smith, 2016). However, those working in practice for between 5 and 10 years were more at risk of burnout and compassion fatigue than those working in practice for less than 5 years or more than 10 years (Smith, 2016). This shows that burnout and compassion fatigue risk increased when remaining in the field for longer than 5 years, literature reviews in healthcare workers show that this is the result of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation (Cocker and Joss, 2016).

McArthur et al (2017) explored compassion fatigue and associated psychological factors in Australian veterinary students, using ProQoL within an online survey. They found that 24% of participants were at high risk and 52% of participants were at average risk of compassion fatigue, highlighting that students are at risk of experiencing compassion fatigue early in their careers. The study also found that 21% of participants reported low compassion satisfaction and identified that veterinary students often felt a lack of autonomy, which may contribute to compassion fatigue. Strategies to help students prevent and, if necessary, cope with burnout should be implemented across training providers and veterinary practices. Students that establish selfcare and coping patterns are more likely to persist into their professional careers (McArthur et al, 2017).

As previously mentioned, Scotney et al (2019) studied burnout and compassion fatigue among workers within animal-based professions; notably, 77% of the veterinary surgeons participants reported moderate to high levels of compassion fatigue. Similarly, 75% of registered veterinary nurses reported moderate to high levels of compassion fatigue, confirming Smiths (2016) findings. As with the literature regarding burnout, further specific research for the prevalence of compassion fatigue among patient care assistants and veterinary receptionists is required.

Moral distress

Moral distress is an area lacking understanding and research in veterinary medicine, although it has been progressively researched within human medicine. Moral distress is an emotional state that arises where a person feels that their ethical principles are different from the external factors which they must undertake (such as company policies or ethical decisions). Lamiani et al’s (2017) systematic review found that moral distress correlated with poor ethical climate, poor job satisfaction and low levels of utilisation and autonomy. They noted that moral distress negatively affects medical professionals’ overall wellbeing and leads to poor job retention. None of the studies in Lamiani et al’s (2017) review explored the impact of moral distress on the quality of care provided, which was noted as an area for further research. Veterinary professionals often find themselves in situations involving conflicts similar to those faced by other health professionals, but some conflicts are unique to the veterinary profession, highlighting the need for further veterinary-specific research.

Moses et al (2018) studied 889 North American veterinary surgeons and established a direct link between compassion fatigue and moral distress. The respondents reported that not being able to do what they believed to be the ethical option caused moderate to severe stress, and empathy for patients and their owners diminished over time. Ethical dilemmas have been reported throughout the literature as the main contributing factor of moral distress - a frequently reported example in the veterinary industry is euthanasia (Manette, 2004; Dow et al, 2019; Matte et al, 2019; Newsome et al, 2019). As yet there is no validated moral distress scale developed for veterinary professionals in order to measure this issue and its contributing factors. Moses et al (2018) hypothesised that veterinarians may not recognise moral distress but describe a situation as ‘sad’ or ‘upsetting’ and consider moral conflicts as part of veterinary practice.

Materials and methods

A questionnaire consisting of both qualitative and quantitative questions was distributed to eligible participants via email, social media and advertising. Participants were selected through purposive sampling, using only those who are members of the veterinary profession currently and who are working in veterinary practice in the UK. Eligible participants for this study include veterinary surgeons, registered veterinary nurses, patient care assistants and veterinary receptionists. The questionnaire used recognised tools including the ProQOL Scoring System (Stamm, 2010) and the Measure of Moral Distress Scoring System - Healthcare Professionals (MMD-HP) (Epstein et al, 2019) to explore these conditions among veterinary professionals. The MMD-HP was adapted to suit veterinary professionals, although the basis of the questions remained the same. Ethical approval for this study was provided by Myerscough Colleges Ethics Committee before commencing (VN2021/01).

Results

The online questionnaire was distributed from 17 September until 31 December 2021; 378 responses were received and 370 participants met the inclusion criteria. Table 1 shows the demographic data. Of the 370 participants, 182 were veterinary surgeons (49.2%) and 169 were registered veterinary nurses (45.7%). The response rate from patient care assistants and veterinary receptionist was low, with five patient care assistants (1.3%) and 14 veterinary receptionists (3.8%) met the inclusion criteria.

Table 1. Demographic data

| Category | Response | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 305 | 82.4 |

| Male | 62 | 16.8 | |

| Transgender | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Age group (years; there were no participants aged 17years or under) | 18-24 | 21 | 5.7 |

| 25-34 | 136 | 36.8 | |

| 35-44 | 91 | 24.6 | |

| 45-54 | 111 | 30.0 | |

| 55-65 | 0 | 0 | |

| 65 and over | 11 | 3 | |

| Type of practice (the ‘other’ group included: equine, rehabilitation, pharmacy, poultry, farm, shelter medicine, exotics/zoo/wildlife) | General - small animal | 257 | 69.4 |

| General - mixed | 31 | 8.4 | |

| Referral | 36 | 9.7 | |

| Out of hours/emergency and critical care | 15 | 4.0 | |

| Other | 31 | 8.4 | |

| Role in practice | Veterinary surgeon | 182 | 49.2 |

| Registered veterinary nurse | 169 | 45.7 | |

| Patient care assistant | 5 | 1.3 | |

| Veterinary receptionist | 14 | 3.8 | |

| Role includes out of hours | Yes | 183 | 49.5 |

| No | 187 | 50.5 | |

| Years of working experience | 0-5years | 77 | 20.8 |

| 5-10years | 70 | 18.9 | |

| 10-20years | 223 | 60.3 | |

| 20+ years | 0 | 0 |

Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (2023) data show that 58% of veterinary surgeons are female and 96.8% of registered veterinary nurses are female; 82.4% of the participants in this study were female. Scotney et al (2019) had similar demographic data in animal-related occupations, with 85.2% of their participants being female.

Burnout, compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and moral distress

Table 2 shows the scoring system used for burnout, compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and moral distress. Guidelines for interpretation for burnout, compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue categories defined a score of 22 or less as being low, 23-41 as moderate and 42 or more as high (Stamm, 2010). As there is currently no recognised measure of moral distress for veterinary professionals, the author opted to adapt the categories of moral distress in a similar manner. Moral distress scores were defined as a score less than 217 as low, 218-434 as moderate and 435-650 as high.

Table 2. Scoring system used for burnout, compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and moral distress

| Category | Grouping | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Burnout numerical score | 22 or less | Burnout level | Low |

| Between 23 and 41 | Moderate | ||

| 42 or more | High | ||

| Compassion satisfaction numerical score | 22 or less | Compassion satisfaction level | Low |

| Between 23 and 41 | Moderate | ||

| 42 or more | High | ||

| Compassion fatigue numerical score | 22 or less | Compassion fatigue level | Low |

| Between 23 and 41 | Moderate | ||

| 42 or more | High | ||

| Moral distress numerical score | 0-217 | Moral distress level | Low |

| 218-434 | Moderate | ||

| 435-650 | High | ||

The mean burnout score was 29.38 (Table 3), indicating moderate levels of burnout across all types of veterinary professions. Despite moderate levels of compassion satisfaction with a mean score of 33.92, moderate levels of compassion fatigue were also reported with a mean score of 27.87. The mean moral distress score was 198.74, indicating low levels of moral distress across all types of veterinary professional.

Table 3. Descriptive data: burnout, compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and moral distress across all types of veterinary professionals

| Variable | n | Mean | SD | Minimum | Median | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burnout score numerical | 370 | 29.38 | 3.809 | 18 | 29 | 39 |

| Compassion satisfaction score | 370 | 33.92 | 6.860 | 13 | 34 | 49 |

| Compassion fatigue (Secondary Traumatic Stress Score) score | 370 | 27.87 | 7.063 | 12 | 28 | 48 |

| Moral distress composite score | 370 | 198.74 | 128.80 | 1 | 175 | 648 |

Impact of role in practice

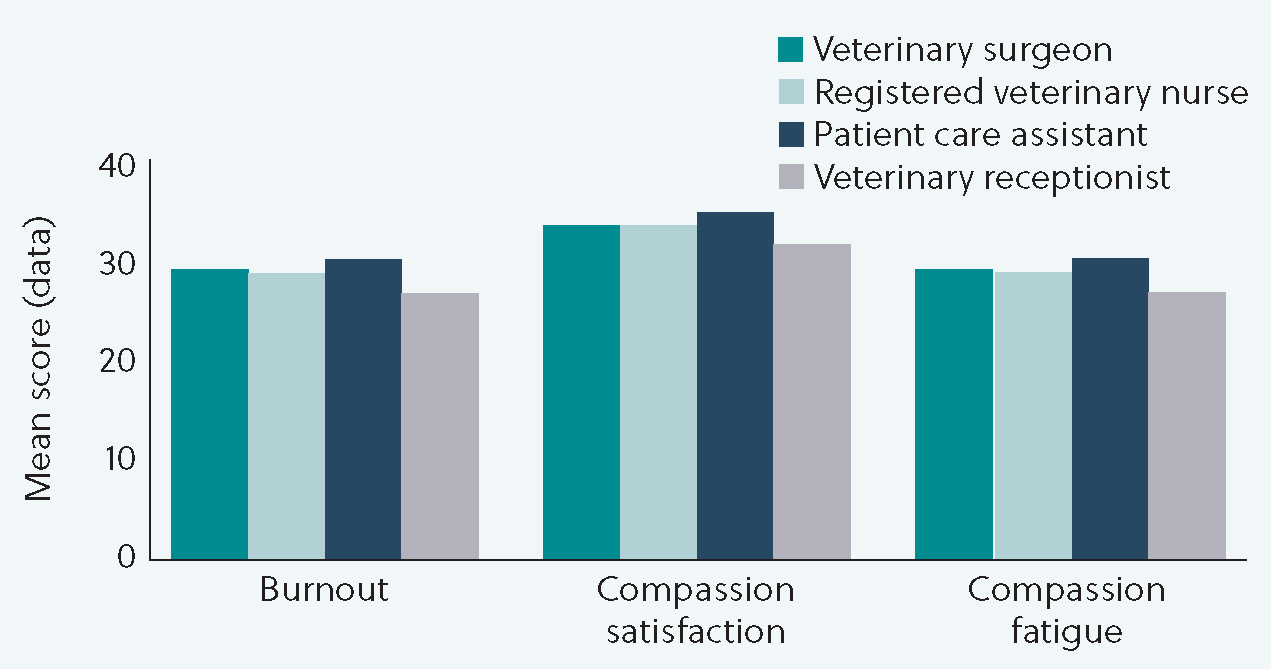

Burnout, compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue scores were relatively similar between each job role ( Figure 1 ). Veterinary surgeons and registered veterinary nurses had similar burnout scores (mean = 29.52, mean = 29.38). Patient care assistants had the highest burnout scores (mean =30.40) and veterinary receptionist had the lowest (mean = 27.14). Patient care assistants had the highest compassion satisfaction scores (mean = 35.20) and veterinary receptionists had the lowest (mean = 31.93). Veterinary surgeons had the highest compassion fatigue scores (mean = 28.07), closely followed by patient care assistants (mean = 28.00) and veterinary receptionists had the lowest (mean = 24.67).

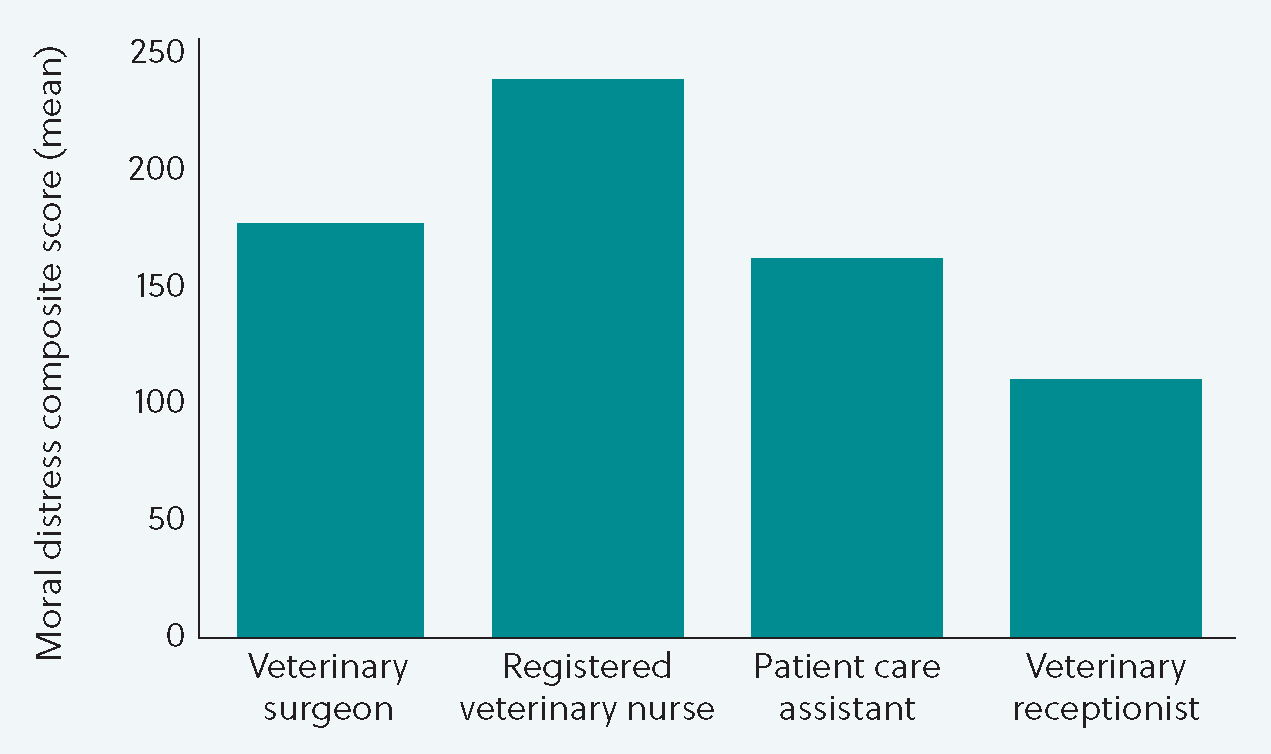

The role in practice appeared to impact the likelihood of moral distress the most. Figure 2 shows that veterinary surgeons (mean = 174.34), patient care assistants (mean = 160.0) and veterinary receptionist (mean = 109.9) all experienced low levels of moral distress, whereas registered veterinary nurses (mean = 233.5) experienced moderate levels of moral distress.

Impact of out of hours work

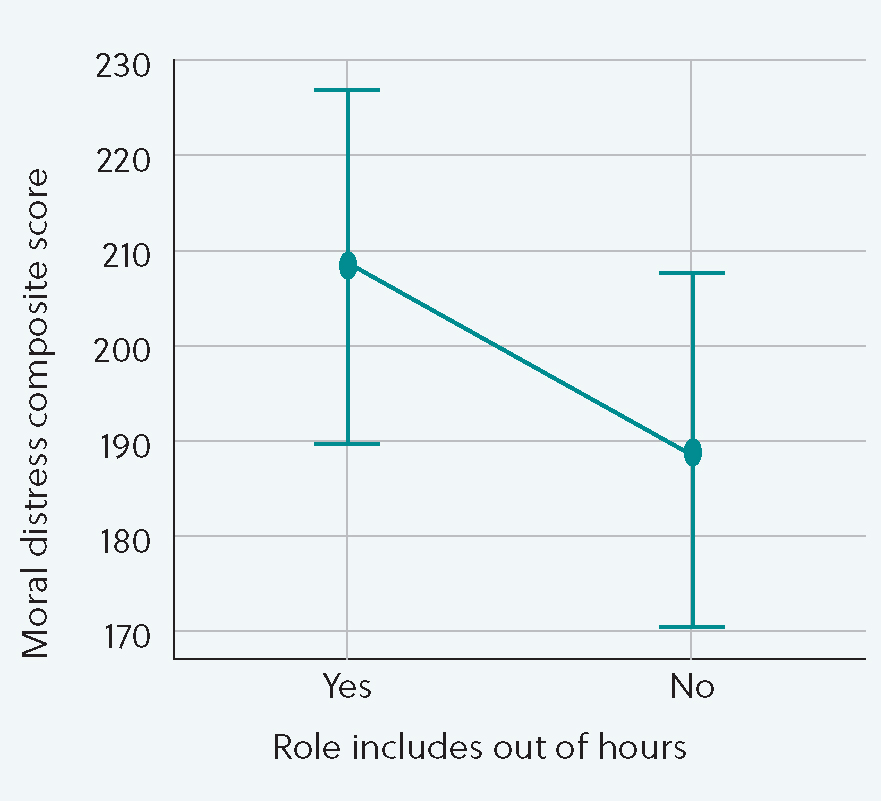

Figure 3 indicates that those who did not undertake out of hours or on-call work were less likely to suffer moral distress (mean = 189) than those who did (mean = 208).

Impact of years working experience in practice

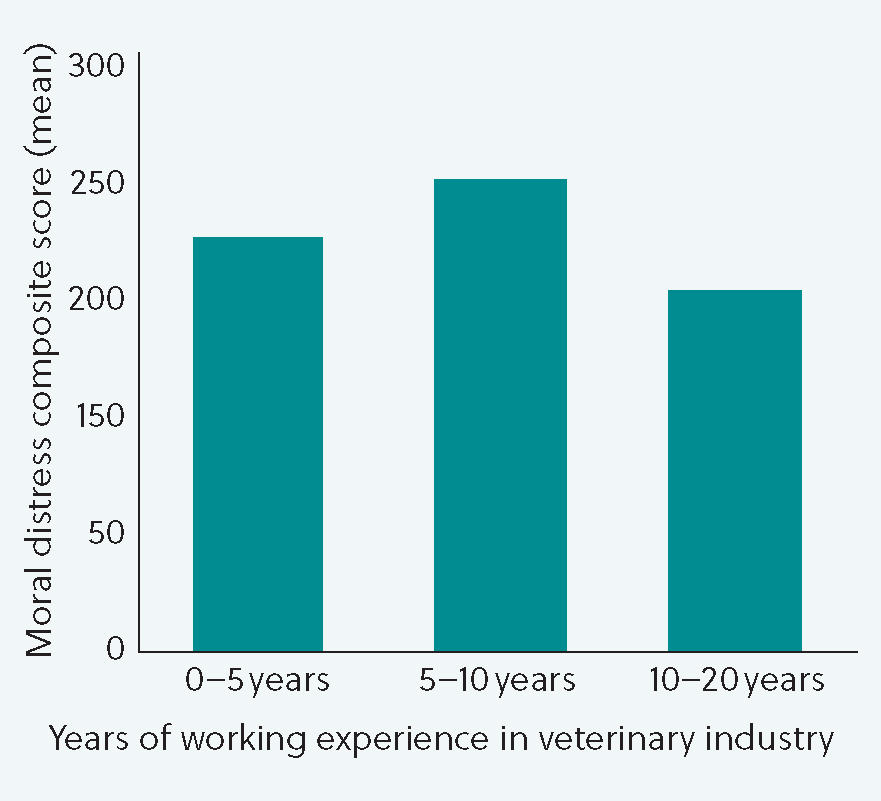

Moral distress was highest in those with 5-10 years’ work experience, and lowest in those with 10-20 years’ work experience (Figure 4).

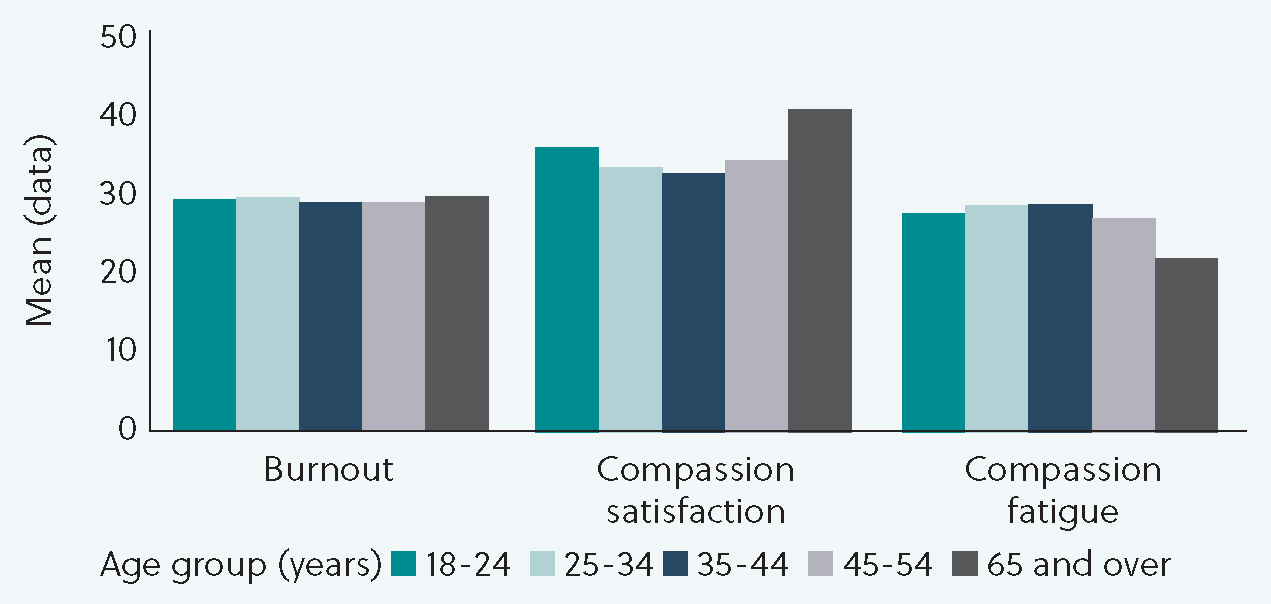

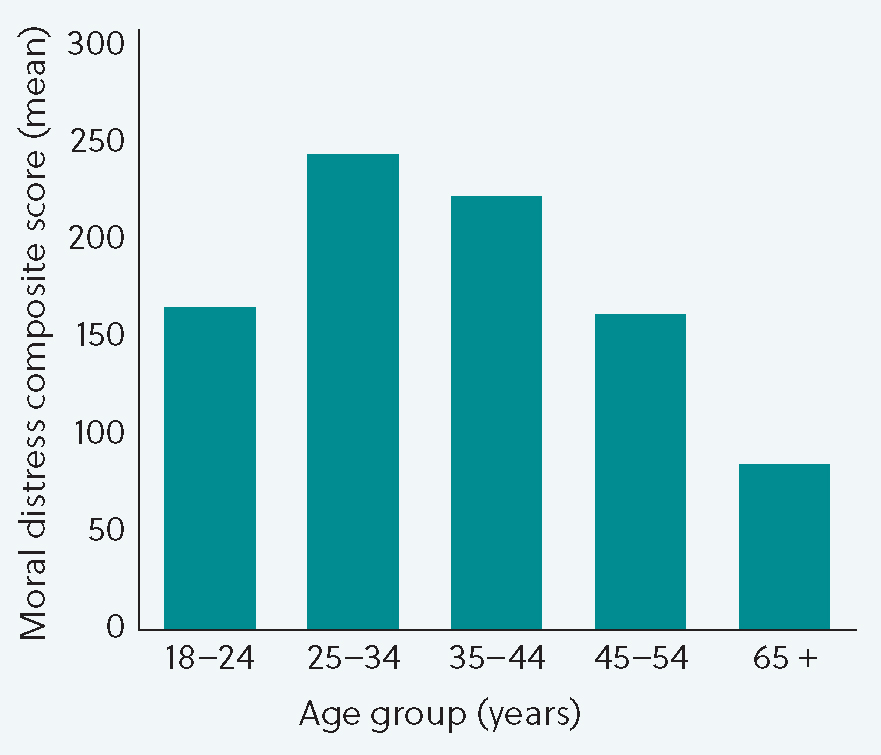

Impact of age

The participant’s age did not appear to impact burnout or compassion satisfaction significantly (Figure 5). However, participants aged 65 years or over ( n=11) had slightly lower average compassion fatigue scores (mean = 21.91) and higher average compassion satisfaction scores (mean = 40.73) compared to the other age groups, as well as the lowest average moral distress score (mean = 80.7) (Figure 6).

Participants aged 25-34 years (n=136) were the most likely to experience moral distress (mean=238.2).

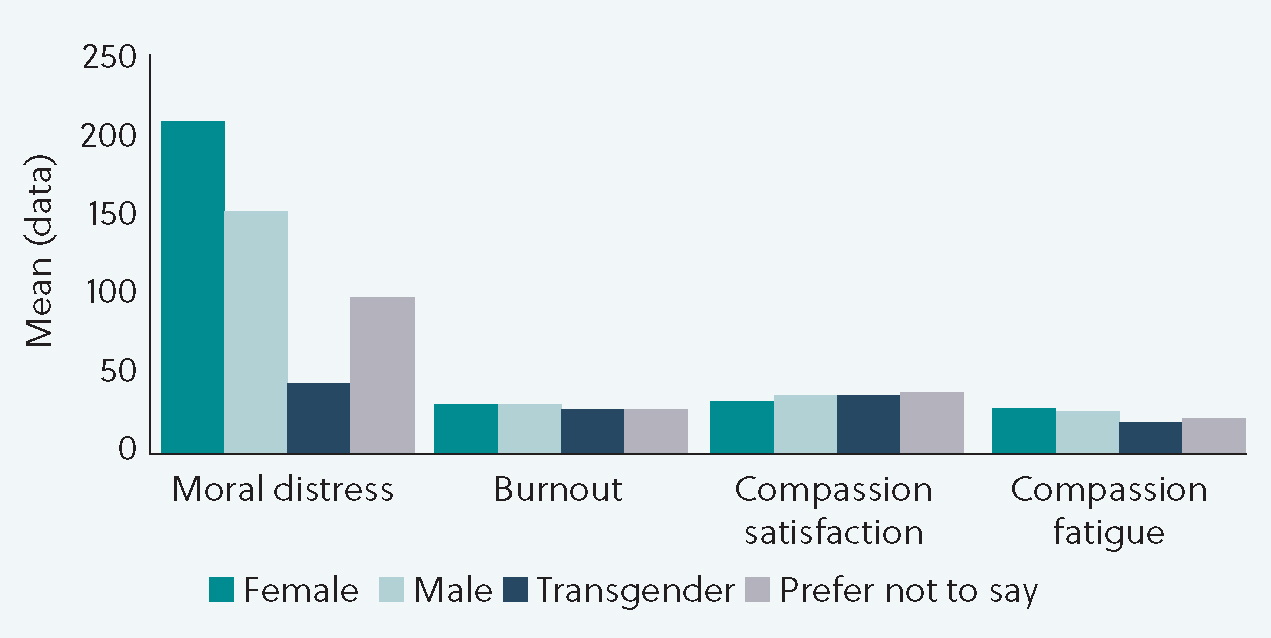

Impact of gender

Gender did not appear to significantly impact burnout, compassion satisfaction or compassion fatigue. Female participants had higher mean moral distress scores (mean = 209.31) than other genders (Figure 7). The sample size for transgender participants or those who did not disclose gender was too small to draw any conclusions (n=3). However, the mean scores for all genders indicate low levels of moral distress.

Mental wellbeing

Table 4 indicates responses for awareness of the conditions, if they had experienced poor mental health and if they would consider a career change to improve mental wellbeing.

Table 4. Responses to mental health-related questions

| Question | Response | Number Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Were you aware of burnout, compassion fatigue and moral distress before this survey? | Yes, I was aware of all three conditions and I have a good understanding of them | 177 | 47.8 |

| Yes, I had heard of them but I did not know the difference between them | 179 | 48.4 | |

| No, I was not aware of these conditions | 10 | 2.7 | |

| I have heard only of burnout | 1 | 0.3 | |

| I have heard only of burnout and compassion fatigue | 3 | 0.8 | |

| Have you experienced poor mental health in the last 12months? (one participant chose not to respond) | Yes | 235 | 63.7 |

| No | 81 | 22.0 | |

| I don’t know | 49 | 13.3 | |

| Prefer not to say | 4 | 1.1 | |

| If so, have you sought professional help? (30 participants chose not to respond) | Yes | 121 | 35.6 |

| No | 219 | 64.4 | |

| Would you consider leaving your current role or a change of career to improve your mental wellbeing? | Yes | 198 | 53.5 |

| No | 83 | 22.4 | |

| Maybe | 89 | 24.1 |

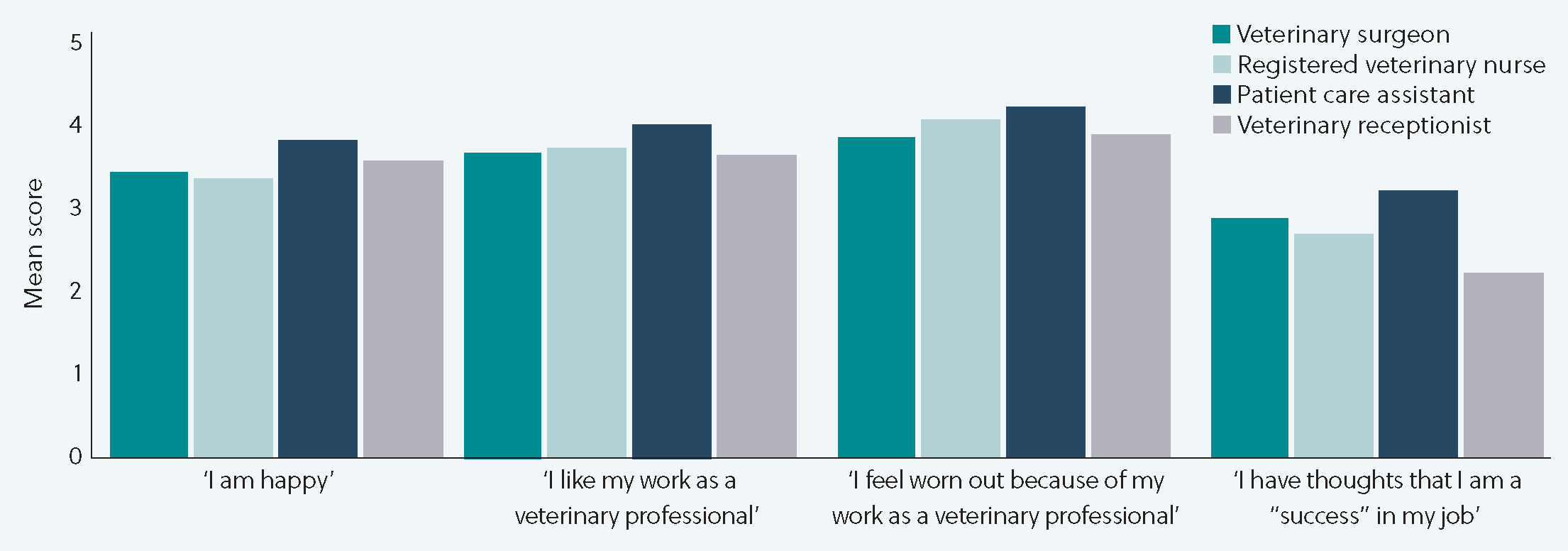

Individual questions were selected and reviewed. Participants rated questions from the ProQOL questionnaire using a Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often), based on their work situation in the past 30 days. For example, the statement ‘I am happy’ highlighted that patient care assistants (mean = 3.8) appeared the happiest and registered veterinary nurses (mean = 3.3) appeared the least happy in their current work situation (Figure 8).

Similarly, responses to the statement ‘I get satisfaction from being able to help my patients’ found that registered veterinary nurses (mean = 4.11) and veterinary receptionists (mean = 4.07) often felt satisfaction from helping patients, whereas veterinary surgeons (mean = 3.96) and patient care assistants (mean = 3.8) sometimes felt satisfaction from helping patients. There was no significant difference between these roles.

Figure 8 shows the answers to the statement ‘I like my work as a veterinary professional’. The results found that veterinary receptionists (mean = 3.64), veterinary surgeons (mean = 3.66) and registered veterinary nurses (mean = 3.71) sometimes enjoyed their work, whereas patient care assistants (mean = 4) often enjoyed their work.

Patient care assistants (mean = 4.2) and registered veterinary nurses (mean = 4.04) often felt worn out because of their work and veterinary surgeons (mean = 3.81) and veterinary receptionists (mean = 3.85) sometimes felt worn out because of their work (Figure 8). Likewise, patient care assistants (mean = 4) often felt overwhelmed by their workload and veterinary surgeons (mean =3.56), registered veterinary nurses (mean = 3.69) and veterinary receptionists (mean = 3.78) sometimes felt overwhelmed by their workload. There was no significant difference between these roles.

Veterinary surgeons (mean = 2.84), registered veterinary nurses (mean = 2.66), veterinary receptionists (mean = 2.21) rarely had thoughts that they were a success in their job and patient care assistants (mean = 3.2) sometimes felt that they were a success in their job (Figure 8).

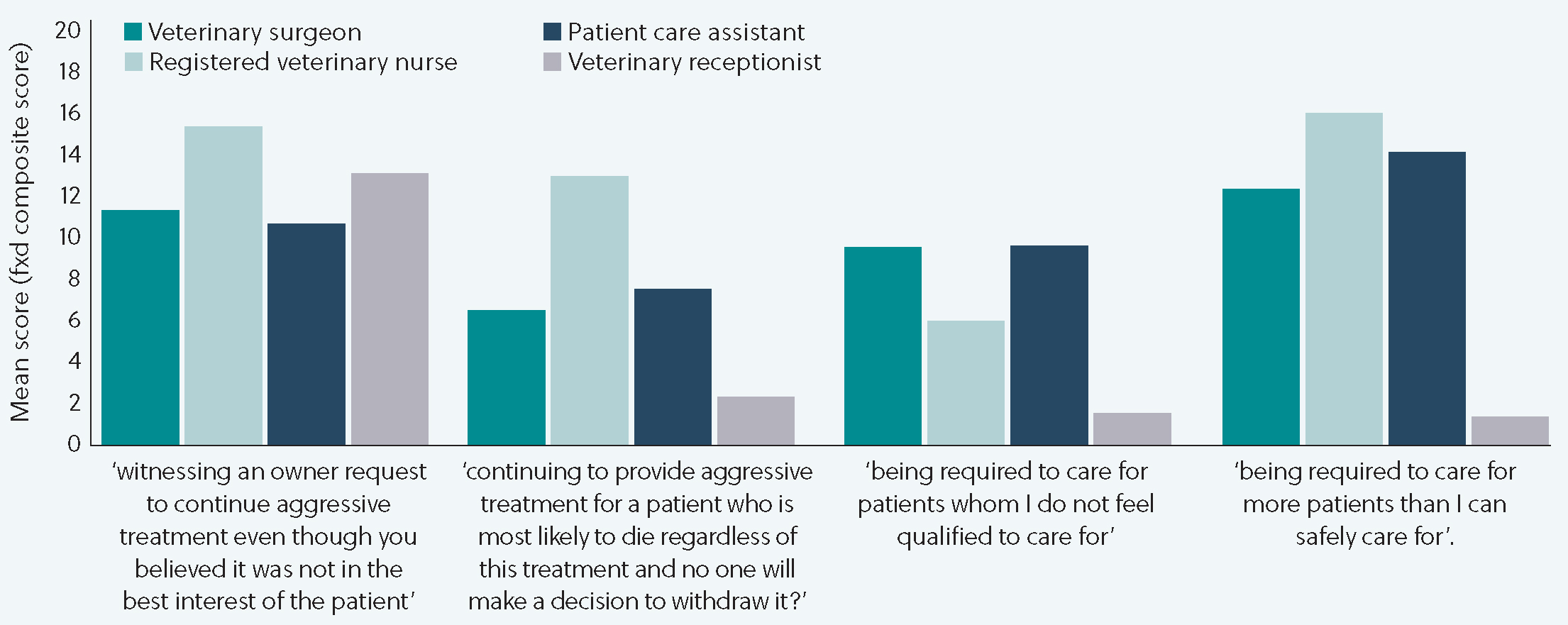

Participants rate each moral distress item on a Likert scale for how often it occurs in their practice (frequency 0 = never, 5 = very frequently) and for how distressing it is when it occurs (distress 0 = none, 5 = very distressing. The frequency score (f) is multiplied by the distress score (d) to create a composite score (fxd, range 0-25). The composite item scores are summed to create an overall mean moral distress score (range = 0-675), with higher scores indicating moral distress.

For example, participants rated how often they experienced and how distressing they found the following situation ‘Witnessing an owner request to continue aggressive treatment even though you believed it was not in the best interest of the patient’. Registered veterinary nurses (mean fxd = 15.23) experienced higher levels of moral distress in response to this situation when compared to veterinary surgeons (mean fxd = 11.20), patient care assistants (mean fxd = 10.6) and veterinary receptionists (mean = 13) (Figure 9).

Similarly, in response to the situation of ‘Continuing to provide aggressive treatment for a patient who is most likely to die regardless of this treatment and no one will decide to withdraw it’, registered veterinary nurses (mean fxd = 12.74) had the highest average fxd composite score indicating higher levels of moral distress (Figure 9).

Figure 9 indicates that patient care assistants (mean fxd = 9.4) and veterinary surgeons (mean fxd = 9.29) had higher fxd composite scores in response to the situation of ‘Being required to care for patients whom I do not feel qualified to care for’.

However, registered veterinary nurses (mean fxd = 15.75) were more likely to experience moral distress in the situation of ‘caring for more patients I can safely care for’ (Figure 9). Interestingly, being required to care for more patients than a veterinary professional can safely care for had the highest average fxd composite score of all the moral distress questions.

Additional questions were used to ascertain information about coping mechanisms veterinary professionals used ( Table 5) and the participants’ understanding of burnout, compassion fatigue and moral distress. There was no correlation between participants who did not use any coping mechanisms (8%) and the compassion fatigue score. There was no significant difference between these roles.

Table 5. Coping mechanisms used by veterinary professionals to improve mental wellbeing

| Coping mechanism | Percentage of veterinary professionals that used this method |

|---|---|

| Self-care | 68 |

| Mindfulness | 37 |

| Exercise | 62 |

| Nutrition | 34 |

| Alcohol or drugs | 18 |

| None | 8 |

| Other methods (including medication, friends/family, faith and prayer, time with pets) | 22 |

However, it was found that participants who used alcohol or drugs (18%) as a coping mechanism had higher average compassion fatigue scores. Veterinary surgeons were more likely to use alcohol or drugs as a coping mechanism than the other roles.

Discussion and recommendations

Burnout, compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction

Burnout scores were moderate across all veterinary professional roles, as were compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue. This indicates that although veterinary professionals have moderate compassion satisfaction, they also have moderate burnout and secondary compassion fatigue. This result contradicts Hansez et al’s (2008) and Smith’s (2016) findings that those experiencing high levels of compassion satisfaction had statistically lower levels of burnout and compassion fatigue, but correlate with Beetham et al’s (2021) findings of average scores of compassion satisfaction despite average scores of burnout and compassion fatigue.

Role in practice did not appear to significantly impact the likelihood of burnout, compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue, although patient care assistants had slightly higher average burnout scores and veterinary surgeons had slightly higher compassion fatigue scores. In response to specific questions, patient care assistants and registered veterinary nurses often felt worn out because of their work and patient care assistants often felt overwhelmed by their workload, indicating signs of burnout. Veterinary receptionists, veterinary surgeons and registered veterinary nurses sometimes enjoyed their work as a veterinary professional, highlighting issues with job satisfaction.

Moral distress was highest in those with 5-10 years’ work experience, and lowest in those with 10-20 years’ work experience. Participants aged 65 years or over had low compassion fatigue, moderate compassion satisfaction and low moral distress scores. This suggests that older participants appeared to be more resilient, while newly qualified and younger participants were more likely to experience these feelings. This correlates closely with Chigerwe et al (2014), Mastenbroek et al (2014) and McArthur et al (2017) findings that veterinary surgeons experience burnout and compassion fatigue as students and early in their careers.

Moral distress

Primary research among veterinary professionals regarding the prevalence and contributing factors of moral distress is extremely limited, especially among registered veterinary nurses, patient care assistants and veterinary receptionists. The role in practice appeared to impact the likelihood of moral distress the most; veterinary surgeons, patient care assistants and veterinary receptionists experienced low levels of moral distress, whereas registered veterinary nurses appeared to experience moderate levels of moral distress. Ethical dilemmas, such as euthanasia, are considered to be the main contributing factors towards moral distress, therefore it was expected that veterinary surgeons would be more likely to experience moral distress (Dow et al, 2019; Newsome et al, 2019). However, on review of individual moral distress questions, registered veterinary nurses were more likely to experience a wider range of ethical situations. The situation of ‘being required to care for more patients than could be safely cared for’ was found to be the most distressing scenario. This may indicate that veterinary professionals are suffering with moral distress for similar reasons to those working in human medicine, such as poor ethical climate, poor job satisfaction and low levels of utilisation and autonomy (Lamiani et al, 2017).

Mental wellbeing

The majority of participants were aware of the conditions and had a good understanding of them or had heard of the conditions but did not know the difference between them. Yet, there was no statistical correlation found between the awareness of the conditions on the average burnout, compassion fatigue and moral distress scores. Of 370 participants, 63% reported they had suffered with poor mental health, yet only 35% of participants sought professional help. Individual coping mechanisms were reviewed, there was no correlation between participants who did not use any coping mechanisms and the impact on burnout and compassion fatigue scores. However, participants who used alcohol or drugs as a coping mechanism had higher average compassion fatigue scores. Over half of the participants said that they would consider leaving their current role or consider a change of career to improve their mental wellbeing. This indicates that although veterinary professionals are aware of these conditions and different coping mechanisms, they are still likely to consider leaving their current role or changing their career to combat these issues.

Limitations

The most significant limitation of the study was the low response rate from veterinary receptionists and patient care assistants (1.3% and 3.7% respectively). This is likely to be because the questionnaire was only advertised on social media. Multiple methods of data collection could have been used to combat this issue. Individual interviews, mailing lists and paper questionnaires may have increased the response rate, although this would have required significant research time and resources. Similarly, multiple questions during the moral distress section posed an issue within the study, as some veterinary professionals gave responses to situations they had not experienced. Although this indicated that veterinary professionals would find certain situations distressing, it is not a reliable finding as they have not experienced them. A smaller survey designed for each individual job role may have helped to combat both limitations.

Recommendations for further studies

This study has highlighted that veterinary professionals are experiencing burnout, compassion fatigue and moral distress, but further small studies for each individual job role are required. The study has highlighted that patient care assistants and veterinary receptionists are experiencing these conditions, although further studies with higher participant numbers would increase reliability. Further exploration of moral distress in registered veterinary nurses is recommended as it appeared to affect them the most, and validation of a veterinary-specific moral distress measurement tool would allow more reliable results.

Recommendations for veterinary practice

This study has highlighted the need to promote mental wellbeing in veterinary practice, alongside support from the education sector to reduce the likelihood of students and newly qualified veterinary professionals experiencing burnout, compassion fatigue and moral distress. All members of the veterinary team could experience burnout, compassion fatigue or moral distress and therefore employers should aim to promote team wellbeing. Promoting veterinary wellbeing by reducing workload, encouraging mental health initiatives, and implementing frameworks to reduce moral dilemmas and aid the euthanasia process, will ensure retention of compassionate and committed veterinary professionals. Implementing resilience programmes as part of veterinary training and continuing professional development may help to lower the overall average scores of burnout, compassion fatigue and moral distress, while improving compassion satisfaction.

Key points

- All members of the veterinary team may experience burnout, compassion fatigue or moral distress; employers and educators should aim to promote mental wellbeing programmes.

- The results of this study indicate that veterinary professionals showed moderate levels of burn out and compassion fatigue, despite moderate levels of compassion satisfaction from their job.

- Veterinary nurses experienced higher levels of moral distress when compared to veterinary surgeons, patient care assistants and veterinary receptionists.

- The study has demonstrated the need to address concerns relating to the mental wellbeing of veterinary professionals.