Despite advancements in the field of veterinary behaviour medicine, undesirable behaviours remain a leading cause of rehoming, relinquishment, and shelter euthanasia in the UK (Diesel et al, 2010; O'Neil et al, 2013; Boyd et al, 2018; Murray et al, 2021). The correlation between undesirable behaviours and canine relinquishment has persisted over several decades, and yet the literature has consistently demonstrated that routine behavioural assessment and canine behaviour management fail to be a standard of care in companion animal practice (Hetts et al, 2004; Christiansen and Forkman, 2007; Roshier and McBride, 2013a; Calder et al, 2017).

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic the UK reported 3.2 million newly acquired pets (Pet Food Manufacturers' Association (PFMA), 2021). Given the imposed lockdown restrictions to veterinary care (British Veterinary Association (BVA), 2021) and the surge in pet acquisition, the availability for veterinary behavioural support was further compromised. In response, impacts on canine health, behaviour and welfare were anticipated by the veterinary community (Dogs Trust, 2020; Christley et al, 2021; Holland et al, 2021). Concerns were substantiated following the results of the Dogs Trust (2020) COVID-19 assessment survey which found over a quarter of canine owners reported a new undesirable behaviour. Coincidingly, within the last 2 years, UK veterinary professionals have reported a 53% increase in dog owners seeking behavioural support, with 57% of practitioners reporting an increase in the number of behavioural cases seen (People's Dispensary of Sick Animals (PDSA), 2020).

With the conjunction of the increase in demand for behavioural care and the considerable growth in pet ownership, there is an urgent need to refocus attention on the provision of behavioural support for dog owners to help prevent and manage behavioural problems thus ensuring good welfare during veterinary visits and beyond. This review will therefore examine the perceptions of the veterinary surgeon and veterinary nurse's role in behavioural medicine as a factor to the provision of behaviour medicine in general practice. It will then discuss reported barriers of care and consider the benefits of applying a behaviour-centred approach in practice.

Veterinary professionals' perceptions of behaviour medicine

If behaviour is an essential consideration in the assessment and treatment of disease (Overall, 2013; Landsberg and Tynes, 2014), then a basic understanding of a dog's natural behaviour is necessary to promote and maintain animal welfare (Golden and Hanlon, 2018; Hargrave, 2019). According to the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) (2014; 2020) day-one competences, veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses are held to a high standard as advocates of animal welfare, through the promotion and maintenance of the physical, emotional, and behavioural needs of the animal (Hargrave, 2019). However, studies have consistently found both veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses feel ill-equipped to recognise, support and manage canine behaviour concerns in general practice (Hetts et al, 2004; Roshier and McBride, 2013a; 2013b; Ryan, 2017; Golden and Hanlon, 2018; Hargrave, 2019). As a result, failure to provide behavioural support at the primary level of care may lead to the potential for compromised welfare.

Behaviour medicine and gender

Few studies have investigated the veterinary surgeon and the veterinary nurse's perception of their role in the assessment and treatment of canine behaviour. An early study by Patronek and Dodman (1999) explored the attitudes of American companion veterinary surgeons on the delivery of behaviour services in practice. Results indicated a gender preference, wherein female veterinary surgeons were more likely to perform routine behavioural examinations and rated the importance of behavioural screening higher than their male counterparts. When accounting for the sex-linked differences in the study, female dominance persisted, suggesting that female veterinary surgeons have a more positive perception of their role in canine behavioural medicine. Similarly, Calder et al (2017) found female veterinary graduates were more likely to complete behaviour surveys and participate in behaviour-focused continuing education. This suggests that earlier findings from Patronek and Dodman (1999) still hold merit nearly a decade later. It must be noted that the latter study was subject to respondent bias with a 90% female participation rate. Sex-linked differences may be attributed to a low male response rate and the concurrent influx of female veterinary graduates from the USA (American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), 2018) at the time of sampling. Given the limitations, controlled studies are required to explore sex-linked differences for behavioural support in general practice, particularly within the UK. Should a gender difference persist in controlled settings, identifying gender factors for the inclusion of behaviour medicine in practice should be established to promote equal opportunity for positive canine welfare.

Role of the veterinary team

A single study known to the author has investigated the perceptions of UK veterinary surgeons in behaviour medicine, and no known studies have evaluated the perceived role of the veterinary nurse. Roshier and McBride (2013a) explored the veterinary perceptions of canine behaviour in two small animal practices in the UK. All veterinary surgeon participants agreed canine behaviour was a significant component of the practitioner's caseload, however, opinions varied on the importance of providing behaviour services in practice and whether behaviour cases should be referred (Roshier and McBride, 2013a). An earlier study by Roshier and McBride (2013b), assessed canine behaviour discussions during wellness visits and found comparable discrepancies in the perception of the veterinary surgeon's role in the provision of behaviour medicine. Canine behaviour was discussed in less than 18% of the assessed routine wellness visits, with no follow-up care and a less-than-10% referral rate (Roshier and McBride, 2013b). In Boyd et al (2018), veterinary surgeons did not routinely offer advice on the management of undesirable behaviours despite owners reporting behavioural concerns during the examination. Across all three studies, demand for behavioural support persisted, yet insufficient behavioural screening and a general lack of behavioural care by veterinary professionals were identified.

Williams et al (2019) studied the views of veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses on the inclusion of stress-reducing methods, a component of behaviour medicine, in UK small animal practice. The participants largely agreed that environmental changes and species-correct handling methods should be employed to reduce stress during veterinary visits (Williams et al, 2019). Additionally, participants noted that veterinary practices could do more to meet the behavioural needs of their patients. Parallel conclusions were drawn by Yeates and Main (2011), wherein veterinary practitioners agreed that more should be done within the profession to address canine behaviour. However, both studies faced selection bias limitations; veterinary professionals who completed the questionnaires may have held a personal interest in canine behaviour, thus positively influencing the results towards the inclusion of behaviour medicine in practice. The influence of personal interest was seen in Luño et al (2017) where veterinary students completing behaviour specialties measured behavioural problems as a ‘more important welfare concern’ when compared with non-specialised graduates of the same year. Therefore, further intervention-based studies are required to explore these relationships to better understand the perceptions of the general practice veterinary team in canine behaviour medicine.

Barriers to the provision of behavioural medicine

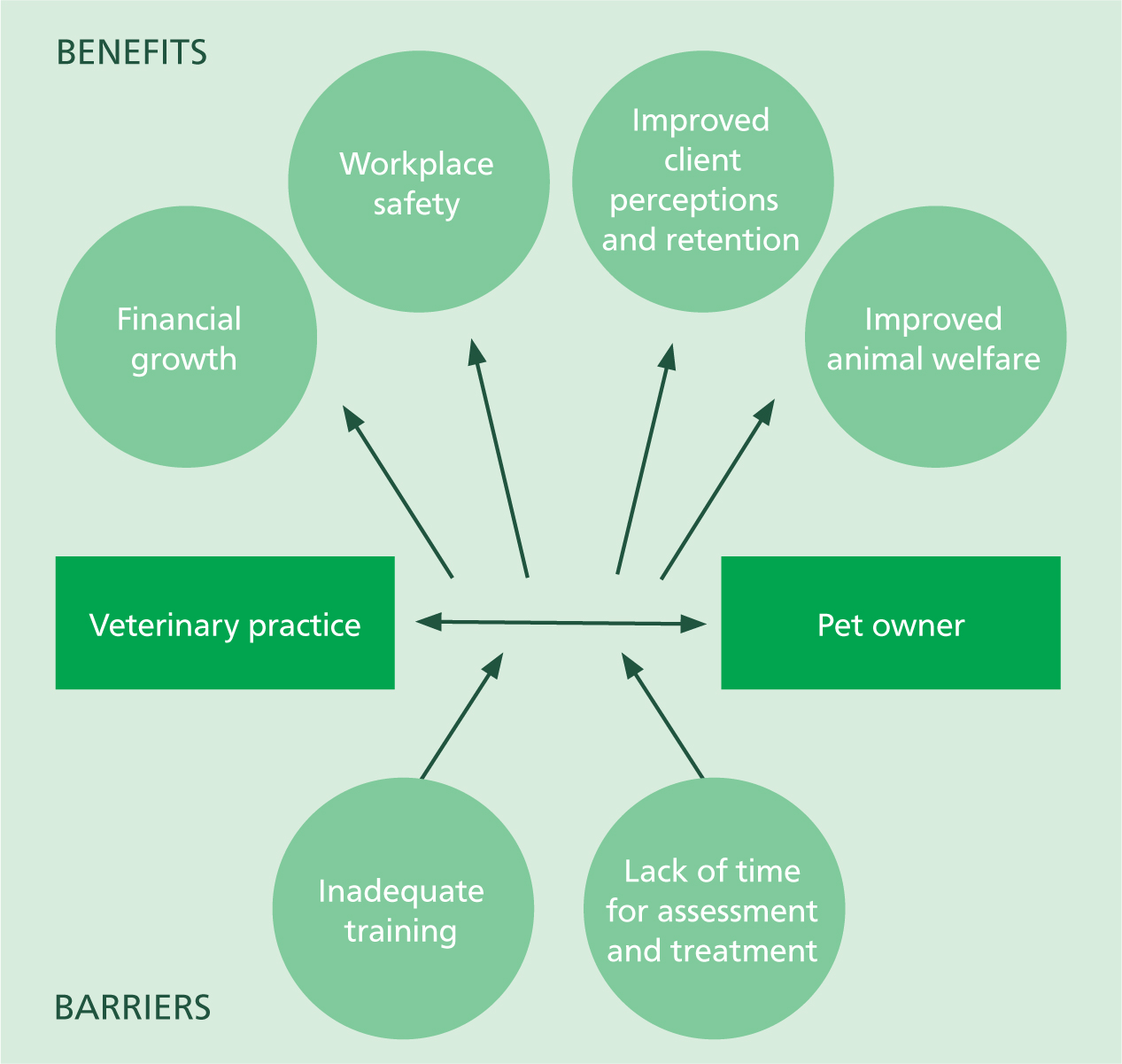

Both empirical and anecdotal evidence supports the demand for behavioural medicine in general practice (Landsberg, 2014; Loftus, 2014; Golden and Hanlon, 2018; Jonckheer-Sheehy and Endenburg, 2009; Murray et al, 2021). Most recently, the 2019 survey by the PDSA indicated 76% of dog owners ‘wanted to change one or more of their dog's behaviours’ (PDSA, 2020). In the 2020 PDSA survey, 41% of owners sought behavioural support by a veterinary surgeon. To meet demand and effectively provide basic behavioural support, the veterinary team requires access to resources and to foundational behaviour education (Jonckheer-Sheehy and Endenburg, 2009; Calder et al, 2017; Hargrave, 2019; Shalvey et al, 2019). Unfortunately, initial investigations to the provision of behavioural services in practice have identified barriers inhibiting the integration of behavioural support. Namely, this includes the lack of behaviour curricula for veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses (Roshier and McBride, 2013a; Loftus, 2014; Golden and Hanlon, 2018; Hargrave, 2019; Shalvey et al, 2019), and a lack of time for the assessment and treatment of problematic behaviours (Figure 1) (Hetts et al, 2004; Landsberg and Tynes, 2014; Calder et al, 2017; Golden and Hanlon, 2018; Hargrave, 2019).

Veterinary behaviour curricula

Historically, the UK veterinary curricula has comprised limited behavioural medicine (Wickens, 2007; Loftus, 2014; Hargrave, 2019). While positive initiatives have been implemented to promote veterinary behaviour medicine in practice, such as the inclusion of animal welfare in the day-one competences (RCVS, 2020), the RCVS has failed to provide curriculum standards and learning outcomes for graduating veterinary surgeons and veterinary nursing professionals (RCVS, 2014; 2020). As a result, there is variation in the proportion of syllabi devoted to behavioural medicine across the UK (Loftus, 2014; Hargrave, 2019), and a reported deficiency in behaviour and ethology teachings (Wickens, 2007). The outcome has led graduates to feel underprepared and ill-equipped to advise clients on basic behavioural concerns (Roshier and McBride, 2013a; 2013b; Calder et al, 2017; Golden and Hanlon, 2018; Shalvey et al, 2019). The Roshier and McBride (2013a) study revealed a lack of preparedness as a result of inadequate training as a primary barrier for the provision of behavioural support. Comparably, Golden and Hanlon (2018) surveyed practitioners and veterinary nurses in Ireland and concluded that lack of undergraduate training was a barrier of service. While causality cannot be determined owing to the cross-sectional design, Golden and Hanlon (2018) further argued that the lack of behaviour curricula has resulted in missed opportunities in the early prevention of problem behaviours. Hetts et al (2004) suggested graduates lacking sufficient knowledge of basic animal behaviour may perpetuate underdiagnosis of behavioural concerns in practice. A comparative analysis of variation in behaviour curricula and comprehensive practice-based examination of day-one competences are required to substantiate these relationships.

Time as a barrier to service

A second barrier identified to the provision of behavioural services was lack of time (Figure 1) (Hetts et al, 2004; Golden and Hanlon, 2018; Hargrave, 2019). The diagnosis of behavioural conditions and subsequent management of the behaviour requires significant time of the veterinary team, from the receptionist to the practitioner (Roshier and McBride, 2013a; Loftus, 2014). Hetts et al (2004) claimed behaviour problem resolution to be the most technically demanding and time-intensive component of behaviour medicine. In Golden and Hanlon (2018), 49% of veterinary surgeons identified ‘lack of time’ as a barrier to the provision of behaviour consultations. Unfortunately, the study failed to discuss average appointment length therefore ‘lack of time’ is subjective to the veterinary surgeon's personal experience. In Roshier and McBride (2013a), practitioners were not awarded longer appointment times to address behavioural concerns. As a result, participating veterinary surgeons argued that the effective management and treatment of undesirable behaviours are best referred to behaviour specialists (Roshier and McBride, 2013a).

Conversely, the opposition contends that behavioural support can and should be effectively integrated into general practice in a timely manner (Hetts et al, 2004; Landsberg et al, 2008; Herron and Shreyer, 2014; Landsberg and Tynes, 2014). The opposition does not assume a full behaviour service to be within the capacity of the general veterinary practice, but rather emphasises the responsibility of the veterinary care team to identify basic behavioural concerns and offer referrals as a standard of care (Landsberg and Tynes, 2014; Hargrave, 2019). Effective integration of basic behavioural support starts with a willingness to initiate behaviour discussions with clients (Hetts et al, 2004), and providing all members of staff with the capacity to determine normal species behaviours and welfare needs (Landsberg et al, 2008; Overall, 2014; Hargrave, 2019).

Benefits to the provision of behavioural services

Workplace safety

Behaviour medicine has a critical consideration for the veterinary practice from safety (Figure 1) (Döring et al, 2009; Calder et al, 2017), financial (Loftus, 2014), medical and ethical perspectives (Csoltova et al, 2017; Golden and Hanlon, 2018). The occurrence of canine fear-related and anxious behaviours is an issue of importance for the safety of the veterinary team, the owner, and the canine (Döring et al, 2009; Ryan, 2017). Research has shown that canines frequently display stress-linked behaviours in the veterinary practice (Stanford, 1981; Döring et al, 2009; Feilberg et al, 2021). In Stanford (1981), 70% of canines would not enter the veterinary practice and in Döring et al (2009) three-quarters of dogs displayed signs of fear, stress, and anxiety (FAS) during routine examinations. Experimental studies have noted physiological stress reactions to veterinary visits (Beerda et al, 1997; van Vonderen et al, 1998; Hekman et al, 2012; Csoltova et al, 2017). Under stressful conditions, handling of fearful animals can lead to the expression of defensive behaviours (Döring et al, 2009; Csoltova et al, 2017) and potential harm to the staff and pet owner (Loftus, 2014; Csoltova et al, 2017; Lord et al, 2020). The inclusion of veterinary behaviour medicine in practice may lead to reduced FAS (Sherman and Serpell, 2008), promoting a safe and low-stress environment to practise veterinary medicine (Landsberg et al, 2008; Sherman and Serpell, 2008; Yin, 2009). Owing to the lack of experimental literature, further inferential studies are required to investigate the significance of behaviour medicine on workplace safety.

Financial benefits

The financial benefits of investing in and implementing behavioural services should be considered (Figure 1). Low-stress handling (Yin, 2009) and behaviour-centred patient handling have been associated with positive client perception of the veterinary team (Sherman and Serpell, 2008; Döring et al, 2009; Yin, 2009; Feilberg et al, 2021), as well as increased client compliance and client retention (Sherman and Serpell, 2008; Yin, 2009; Knesl et al, 2016; Calder et al, 2017). Owners may refuse veterinary treatment or may not return to the practice if they perceive that their dog had a negative experience (Döring et al, 2009; Knesl et al, 2016; Calder et al, 2017). Loftus' (2014) discussion of behavioural considerations for the veterinary practice implies that behaviour-friendly practices reap financial gain through increased owner compliance, repeat visits and word-of-mouth advertising. Unfortunately, empirical studies were not provided to support these claims. In Calder et al (2017), the relationship between behavioural services and practice revenue was significant, although the findings were representative of a teaching hospital rather than private practice. Nevertheless, studies have demonstrated that the veterinary-client relationship can be enhanced by the use of methods to reduce stress responses during veterinary visits, thus increasing revenue. Future longitudinal studies are required to investigate the relationship between financial gain and behaviour-centred patient care.

Improved diagnostic quality

A behaviour-centred approach to patient care is said to improve the thoroughness of the veterinary examination along with diagnostic quality (Figure 1) (Csoltova et al, 2017; Ryan, 2017). When a dog is actively defensive and intolerant of a complete physical examination, diagnostic accuracy may be compromised, leading to the potential for misdiagnosis (van Vonderen et al, 1998; Csoltova et al, 2017). In canines, stress indicators are behavioural, physiological and immunological (Beerda et al, 1997), and are known to increase during veterinary examinations (Beerda et al, 1997; van Vonderen et al, 1998; Döring et al, 2009; Csoltova et al, 2017). For instance, in van Vonderen et al (1998) the misdiagnosis of hyperadrenocorticism, via elevated urinary corticoid:creatinine ratios, was associated with stressful sampling conditions. However, the study did not control for both positive and negative arousal associated with cortisol elevations (Nicholson and Meredith, 2015). Sherman and Serpell (2008) used behavioural assessment as a tool to monitor the response to treatment, level of pain, the state of disease and quality of life of the canine. Consequently, the incorporation of behaviour-centred medicine may help with earlier diagnosis (Loftus, 2014), improved quality of care (Csoltova et al, 2017) and, ultimately, the promotion of animal wellbeing and welfare (Sherman and Serpell, 2008; Ryan, 2017).

Conclusion

Demand for behavioural services in general practice has been identified (Golden and Hanlon, 2018; PDSA, 2019; 2020; Jonckheer-Sheehy and Endenburg, 2009); however, routine behavioural assessment has yet to become a standard of care in the UK (Patronek and Dodman, 1999; Döring et al, 2009; O'Neil et al, 2013; Roshier and McBride, 2013a; Calder et al, 2017; Boyd et al, 2018). This may be owing to the perception of the veterinary practitioner as an intermediary for referral behavioural services (Roshier and McBride, 2013a; Landsberg et al, 2008; Loftus, 2014; Hargrave 2019), the lack of undergraduate veterinary behaviour curricula or lack of continuing behavioural education for veterinary professionals (Wickens, 2007; Loftus, 2014; Hargrave, 2019). Nonetheless, canine owners have come to expect veterinary professionals to provide behavioural services (Patronek and Dodman, 1999; Mills and Zulch, 2010; Calder et al, 2017) highlighting a need for evidence-based, accurate and current behaviour information for the entire veterinary team.

KEY POINTS

- Since 2019, there has been a significant increase in the demand for canine behavioural support at the primary level of care within the UK. However, routine behavioural assessment and behaviour management fail to be a standard of care in companion animal practice.

- Veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses differ in their perceptions of their role in canine behaviour medicine, with most feeling ill-equipped, underprepared and lacking basic knowledge of species-specific behaviour to effectively support clients with dogs exhibiting behavioural concerns.

- Should the barriers to the provision of behavioural support be addressed, then applying a behaviour-centered approach to veterinary care may lead to financial gain, improved client-retention and compliance, better workplace safety and improved diagnostic quality.