The aim of this article is to provide an up to date overview of this disease and highlight key aspects of nursing care and owner support. Immune-mediated thrombocytopenia (IMT) is the most common cause of a low platelet count seen in dogs. Destruction of the platelets occurs when immunoglobulins attach to the platelet surface, causing macrophages to respond and initiate phagocytosis (Harvey, 2011). Primary IMT is idiopathic and only diagnosed after the exclusion of the causes of secondary IMT and other causes of thrombocytopenia, such as bone marrow disorders. Secondary IMT can result from an infectious agent, such as viral, bacterial or parasitic organisms, neoplasia or a drug-induced aetiology, such as the use of sulpha-based antibiotics (Cummings and Rizzo, 2017). Blood transfusion may also induce IMT (Day and Kohn, 2012).

Signalment

This is a common disease and occurs more frequently in dogs than cats. Signalment is strongly associated with Primary IMT (Day and Kohn, 2012). Documented breed pre-dispositions include; Cocker Spaniels (Figure 1), Miniature and Toy Poodles, Golden Retrievers, German Shepherds and Old English Sheep Dogs. Females are twice more likely to be affected than males (O'Marra et al, 2011). Age of onset reported in the literature ranges from <1–14 years, however, the majority of cases are reported with a median age between 4–8.1 years (Lewis and Meyers, 1996; O'Marra et al, 2011; Day and Kohn, 2012).

Symptoms and diagnosis

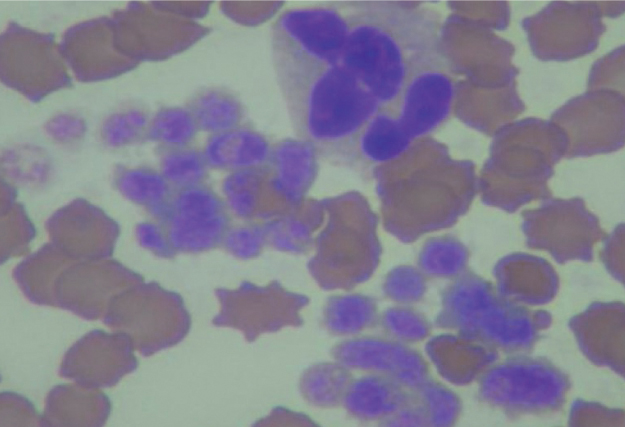

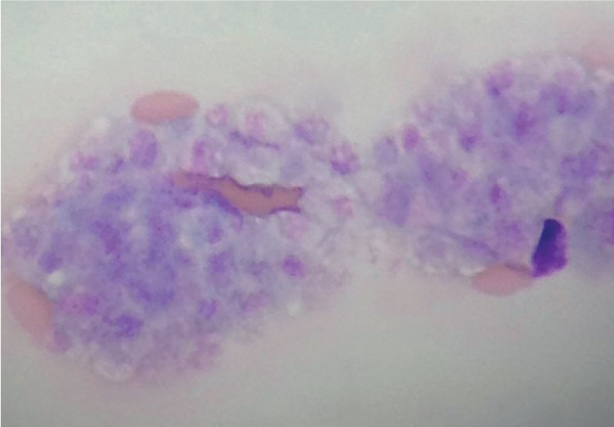

Owners may present their pets with lethargy, weakness, anorexia and mild pyrexia. The usual signs of platelet dysfunction may be observed on examination, such as bruising of the skin (petechiae or ecchymosis), epistaxis or rhinorrhagia in more severe forms, haematuria, gingival or ocular haemorrhages. Up to 50% of cases may present with splenomegaly (Harvey, 2011). A normal platelet count can be within the range of 200–400 109/litre (Day and Kohn, 2012). Spontaneous haemorrhage will usually suggest a platelet count of less than 30–50 x 109/litre. A low platelet count may be the only haematological abnormality in primary IMT. However, only 5–15% of IMT cases will be idiopathic in origin (Park et al, 2015). When using a commercial haematology machine in-house, a blood smear is required for visual analysis, particularly when the result is abnormal. Platelet count results from commercial machines can be unreliable, especially if there is platelet clumping or macro-platelets in the sample (Figure 2).

Blood smear — production

Producing a good quality smear requires practice and consistency, which are essential for appropriate diagnostic quality. Smears made from a fresh ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) sample, as soon after collection as possible, will result in increased diagnostic quality. Smears produced from samples older than 24 hours will frequently show ageing changes that often impedes/interferes with the interpretation. After adequate drying, the smear can be stained with a commercial stain such as Rapi-Diff or Diff-Quik. These stains should be regularly replaced, rather than just topped up, to reduce artefacts on the smear during the staining process. Once stained, smears should be stored at room temperature.

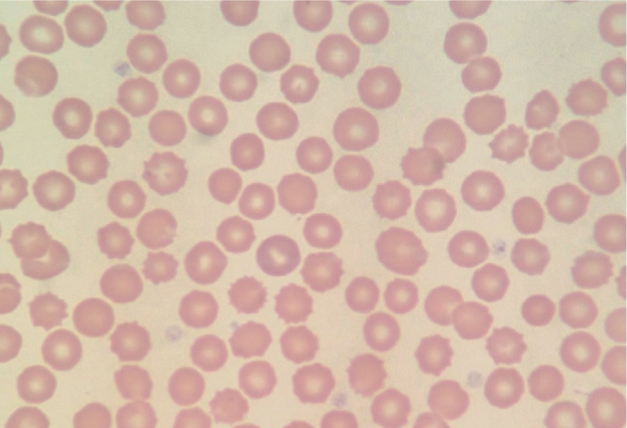

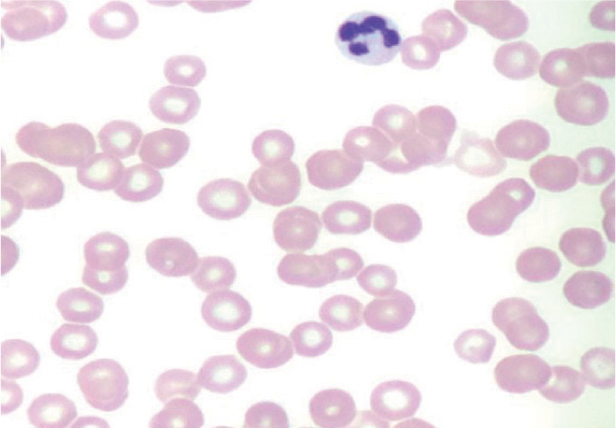

Blood smear — platelet examination

In dogs, platelets do not have a nucleus and are normally one quarter the size of a red blood cell. They have an irregular, circular outline with a pale purple-pink granular appearance (Figures 3 and 4). When examining the stained and dried smear, first check the feathered edge for large clumps of platelets, these can result in a false low reading on the haematology machine (Figure 3). Then examine the mono-layer, just behind the feathered edge using a methodical technique, such as the battlement method. Examine 10 separate fields using this technique, and note the number of platelets in each field. In a healthy patient, there would typically be 10–30 per oil immersion field (Figure 4). Generally, if there are only 2–3 clumps, with a low machine count and no other platelets visible (Figure 5), it is likely the overall count is low.

Prognosis

A recent study of 45 dogs by Simpson et al (2018), following cases up to 1 year after diagnosis, stated a mortality rate of 11.9%. They reported 89.6% survived to discharge and 31% of those relapsed, within an average of 79 days after successful treatment. Short-term survival rates are suggested to be 74–97%, with a recurrence rate of 26-58% (O'Marra et al, 2011). Cases presenting with melena or raised blood urea nitrogen (BUN) are at greater risk of mortality, with only around a 60% survival rate (Cummings and Rizzo, 2017).

Treatment

This will be determined by a multitude of factors, especially when relating to secondary IMT, as the underlying cause will require targeted treatment. However, in all cases there will need to be a degree of immunosuppression to prevent the destruction of platelets by the reticulo-endothelial system. The goal of immunosuppressive therapy is to increase the platelet count to >40 x 109/litre. The following treatments were reviewed by Nakamura et al (2012).

Corticosteroids

Commonly prednisolone is the first-line choice, providing a consistent and low cost immunosuppressive therapy and should achieve a satisfactory increase in platelet counts within 7 days, to >50-100 x 109/litre. This will greatly reduce or remove the risk of spontaneous haemorrhage.

Other immunosuppressant therapy

Alongside corticosteroids, the veterinary surgeon may prescribe a concomitant therapy with different classes of immunosuppressive drugs. This can reduce the dose required of corticosteroid and the associated side-effects, although cost may be increased. Azathioprine at 2 mg/kg/day can be used, but will be of little benefit in acute cases as it may take over 4 weeks to achieve the required response. Cyclosporine has demonstrated efficacy in dogs with immune disorders, but the side effects include gastro-intestinal (GI) signs, anorexia and weight loss. Mycophenolate mofetil has been used with corticosteroids and has shown comparable results when compared with a cyclosporine-corticosteroid combination, with fewer side effects and lower cost, therefore this may be an emerging alternative (Cummings and Rizzo, 2017).

Vincristine

Traditionally used as chemotherapy for oncology patients, vincristine is known to stimulate the production of platelets in healthy dogs; studies have shown it can benefit the recovery of patients with acute IMT, with a single dose administered in addition to corticosteroid therapy (Rozanski et al, 2002; Park et al, 2015). However, the side effects associated with chemotherapy should be carefully considered and discussed with the owner. This should include managing urinary and faecal excretion with consideration for owner and public safety. In cases that do not respond to traditional therapy (refractory IMT), or those that have intolerance to steroid treatment, vincristine loaded platelet therapy may offer an alternative solution. This type of therapy targets the vincristine to the antiplatelet antibodies, thus destroying the phagocytic cells that are engulfing the platelets (Park et al, 2015).

Splenectomy

An alternative treatment option for steroid-refractory or dependent immune thrombocytopenia patients includes splenectomy. This option is usually reserved for patients that fail to respond well to all other medical therapies. By removing the spleen, the primary site for clearance of the platelets is eliminated, this also prevents the production of autoantibodies. There is limited research in this field however, survival and remission statistics for patients that require this level of intervention varies greatly based on individual status, and many require long-term medical management (Scuderi et al, 2016).

Nursing the IMT patient

Nursing patients with IMT can be challenging, it is important to consider the care of the patient holistically in order to identify deterioration and prevent self-trauma (Garland, 2011). The accommodation provided should be suitably padded, ensuring comfort and protection from surfaces which may cause localised haemorrhage. The environment needs to be quiet and calm to encourage the patient to settle adequately. Patients with acute IMT or in crisis will typically be lethargic and depressed, however due to the scope in clinical presentation, ages affected and individual tolerance to symptoms, this is not always the case (O'Marra et al, 2011). Some dogs can become distressed when in the hospital environment, this can make management complicated as high levels of stress and agitation may increase blood pressure, heart and respiratory rate and the likelihood of self-inflicted injury (Scotney, 2010). Nursing interventions to calm the patient including audio enrichment, pheromones and boredom breakers could be introduced with positive impact, however need to be managed to prevent over stimulation or gum abrasions on toys for example (Lloyd, 2017).

Creating a detailed nursing care plan is vital for the continuous and seamless delivery of treatment and review. Patient observations need to be recorded comprehensively in order to accurately monitor changes, this includes observations of petechiae to the mucosal membranes and pupils. Photographing or drawing the extent of this will allow thorough progress reports to be formed, which may impact treatment plans and increase communication among the team (Chartier, 2015). Regular urinalysis and haematology is also advised including packed cell volume and blood smears to evaluate secondary changes post diagnosis as well as monitoring changes to the mean platelet volume (Schwartz et al, 2014). Strategic sample site selection can help to reduce subcutaneous bleeding. Utilising the peripheral limbs will allow suitable pressure to be applied post sampling and inflict less trauma (Herring and McMichael, 2012). Injections, intravenous fluid therapy and infusions are challenging to manage, where appropriate, oral medication should be favoured. If essential, intravenous catheters can be used, however, these require close monitoring and strict hygiene management to ensure patency and reduce localised trauma (Schwartz et al, 2014).

Signs of anaemia, epistaxis and dyspnoea should be monitored closely (Figures 6 and 7), as well as increasing haematuria and haemochezia (Viviano, 2013). Hypovolaemia can be seen in some severe cases, especially where gastrointestinal haemorrhaging is present, as this route facilitates large volumes of blood loss. Patients experiencing severe haemorrhage can be given platelets either via platelet-rich plasma or fresh whole blood transfusions, although this will help to prevent loss of life, the impact this will have on the platelet count longer term is minimal since they will be rapidly destroyed (Nakamura et al, 2012). Alternatively, these patients can be provided with crystalloid or colloidal infusions to combat hypovolaemia, and any indication of anaemia can be addressed with packed red blood cell or fresh whole blood transfusions (Nakamura et al, 2012).

There are various side effects associated with some of the primary treatments, many of which may be given at an aggressive dose. Commonly, corticosteroids are prescribed at high levels to suppress the immune system quickly (Cummings and Rizzo, 2017). The rapid onset, which is beneficial to the condition, is associated with a change in clinical signs, this includes, but is not limited to: sudden changes of behaviour; polydipsia/polyuria; polyphagia; and excessive panting. Ensuring the patient has access to water and toileting facilities can be time consuming but needs to be factored into ward duties. Due to the sudden suppression of the immune system is it also advisable to instigate reverse barrier nursing (Wang et al, 2013). Once the patient's status has stabilised a home care plan should be formulated for discharge, this should be considered in conjunction with the owner to ensure a realistic plan is agreed.

Owner relationship management

The process of treating and supporting patients with IMT can be prolonged and costly. Factors affecting owner compliance have been studied previously with mixed results, the scope of individual clients' needs differs greatly and therefore presents an issue across the industry (Wareham et al, 2019). Trust and understanding are vital when advising clients on health care, this is especially important when considering the long-term administration of pharmaceuticals and care. The methods used to communicate this to the client should be well adjusted for their individual needs, considering a range of circumstances (Gerrard, 2015). Ensuring the correct support structures are in place to aid owners is essential, and practices should strive to build a strong rapport with clients and provide suitable information to encourage compliance (Best, 2013). The best way to achieve this is to involve them in all discussions and reassessments of the patient, including treatment options. Although this is time consuming and requires a great deal of sensitivity and interpersonal skills, the relationship gained will have long-term benefits (Loftus, 2012).

Before discharging it is beneficial to conduct a consultation to discuss home care (Figure 8). This should include costs involved with treatment, behavioural changes, managing immune suppression, changes needed to the home and prognosis (Notari et al, 2015).

There are some key elements which can optimise communication, consider:

- The environment and tone of practitioner

- Advising the client in advance of the time you will need to discuss their pet, this will prevent clients rushing to leave and missing the information

- Condition-specific hand outs

- An individualised plan; owners can be reassured by advice that is specifically for their animal, avoid generic discharge sheets

- Using demonstrations; it is always a good idea to see what method will work for the patient so you can give the owner confidence and introduce the patient to the new routine. Positive reinforcement is key here for long-term medicating.

Once discharged, a follow-up call over the next couple of days is a good way to reinforce your support to the client and gain an idea of the patient's progress. At this point any emerging issues can be resolved and you will allow the owner the opportunity to ask questions they potentially had not previously considered (Gerrard, 2015). Follow up consultations should be arranged with the veterinary surgeons or veterinary nurses depending on the context. By utilising a combination of the two, clients can be supported by the appropriate member of the team.

Understanding the side effects

Owners need to be prepared and take a preventative approach where possible with regard to side effects. Some of the most prominent issues that arise from treatment include (Cummings and Rizzo, 2017):

- Skin break down and infection — high doses of steroids weaken the skin and allow bacteria build up. Consider the home environment and exercise areas, maintaining hygiene can help to reduce infection risk. Exercise areas may also need to be considered as rough terrain or woodland for example may increase the instance of small skin abrasions or cuts via bushes and branches thus increasing the opportunity of localised skin infection to occur.

- Polydipsia and polyuria — can be complex to manage and distressing to all parties. Owners need to record their routine in a diary and try various methods to control the increased urinary output as this tends to be one of the least favoured side effects seen.

- Polyphagia — can be managed by increasing food volume and decreasing the average calorie intake per meal. One of the best ways to meet the mental need of the patient is to break down their meals into multiple feeds per day and add some form of puzzle to each feeding session. This will prolong the activity, allow cognitive engagement, and entertain the patient thus calming them overall. It is important to remember that although weight gain can be seen with steroid use, high doses often result in muscle and weight loss whilseincreasing the appearance of a pot belly.

- Behavioural changes — can include stress behaviour, panting, change in tolerance to other pets and children, possession (food especially) and depression. Behavioural changes should be recorded by the owner and used to assess the quality of life of the patient while considering suitable adjustment and counter protocols.

- Fatigue — owners should refine the exercise routine of the patient to ensure they are not stressed physically. In the early stages of treatment exercise is contraindicated in many cases due to the risk of bleeding, exacerbated by high blood pressure and physical exuberance.

- Gastrointestinal signs — some medications can cause diarrhoea and gastrointestinal (GI) tract bleeding, this can be evaluated via faecal analysis.

- Pancreatitis — this can be a complex issue thought to be primary with IMT or a secondary reaction to inflammation or due to bleeding into the pancreas.

Managing expectations

If surgical options are considered, such as splenectomy, it is important for the owner to understand the added complications of wound management, as well as the increased surgical risk and costs involved. Wound management of immunosuppressed patients, on pharmaceuticals which inadvertently reduce healing, will usually require additional time, monitoring and nursing (Notari et al, 2015).

It can be hard to discuss euthanasia, if the treatment is unsuccessful. However, for the preparation of the owner and the quality of life of the patient it is good to have a clear idea from the beginning, this will enable the client's expectations to be managed and make the welfare of the patient easily placed at the forefront of every decision. When tapering down the doses there is potential for both positive and negative results to be seen and often a mixture (Simpson et al, 2018). This can be frustrating and upsetting and needs to be managed with care. When there is little to no hope of the patient making a full recovery, there needs to be an open discussion about the patient's ongoing quality of life. During this time, the relationship your practice has worked so hard to achieve will be put to the test, often rewarding your efforts. Via the partnership built with clients the ability to have these discussions can be easier, and although the emotional investment has not had the desired outcome, clients should feel able to confide in the team you have created (Best, 2013).

Conclusion

IMT is a common condition in dogs, which overall has a good recovery rate, although this is reduced to 60% if presenting with melena or raised BUN. Nursing care should focus on monitoring and minimising haemorrhage, and incorporating detailed planning and recording of the patient's condition. Treatment and associated side effects of steroid therapy can be difficult and distressing for the owner to manage after discharge. Therefore, it is vital to establish close support and communication from the onset and maintain this during the tapering of therapies.

KEY POINTS

- Immune-mediated thrombocytopenia (IMT) is a common condition in dogs and can be primary or secondary in nature.

- Diagnosis is made by evaluating clinical signs and performing a platelet count.

- Treatment usually includes aggressive immunosuppressive therapy, which can frequently be associated with multiple side effects.

- Nursing care plans will incorporate detailed observation records and support to monitor and minimise haemorrhage.

- Owner communication and support from the point of diagnosis is vital in the longer term after discharge, to ensure compliance and appropriate management.