Keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) (also called dry eye) describes a deficiency of the aqueous portion of the tear film of the eye. Good tear production lubricates, cleans and provides nutrition to the cornea. Diagnosis is supported by Schirmer tear testing (STT), with normal dogs showing reading >15 mm/minute. Readings below 10 mm/minute confirm KCS, while readings 10–15 mm are suspicious. KCS has important welfare impacts because it is a longterm condition that is associated with ocular irritation and can lead to corneal ulceration. Awareness of which animals are predisposed can assist the veterinary nurse to advise owners on how to avoid buying a high-risk breed and how to detect cases earlier. Previously reported predisposed breeds include English Bulldog, West Highland White Terrier and Pug, but much of this earlier research is now either out of date, was not carried out on UK dogs or was based on referral cases that are very poorly representative of the wider primary-care dog populations. More reliable information based on the general UK dog population is needed. In the UK, the RVC's VetCompass Programme collates de-identified electronic clinical data on over 15 million companion animals from over 1800 primary-care veterinary practices for epidemiological research. Powered by VetCompass, a new study has now reported the frequency of KCS in dogs under primary-veterinary care in the UK and evaluated predispositions such as brachycephaly.

From 363 898 dogs under primary veterinary care at 300 UK practices, there were 1456 confirmed KCS cases. The 1-year prevalence was 0.40% (95% CI 0.38–0.42). With one in every 250 dogs affected in the UK, this shows the high importance of KCS to dog welfare. The breeds with the highest KCS prevalence were American Cocker Spaniel (5.90%), West Highland White Terrier (2.21%,), Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (1.91%,), Lhasa Apso (1.86%,) and English Bulldog (1.82%,). This highlights an almost epidemic proportion of KCS in some breeds, with over one in every 20 American Cocker Spaniels affected. The median age at first diagnosis of KCS was 7.5 years. With an earlier VetCompass study reporting 12.0 years as the overall median lifespan of UK dogs, this further highlights the worrying welfare impact from KCS with most affected dogs expected to suffer from the condition for over 4.5 years.

So, what factors were associated with increased odds (risk) of KCS, and could therefore assist the vigilant veterinary nurse to identify animals at higher risk of KCS? The new study identified several key factors for veterinary nurses to look out for: breed, bodyweight and age. The study identified 22 breeds of UK dogs at increased risk compared with crossbred dogs. Four breeds had especially high risk: American Cocker Spaniel (x 52.3), English Bulldog (x 38.0), Pug (x 22.1) and Lhasa apso (x21.6). When all dogs were grouped based on skull shape, brachycephalic (flat-faced) dogs had 3.6 times increased risk compared with mesocephalic (medium-length skull) dogs. Spaniels overall had 3.0 times risk compared with non-spaniel dogs. At a population level, smaller dogs had higher risk overall. Dogs weighing 10 kg to 20 kg had 5.5 times risk compared with dogs weighing 30 kg to 40 kg. However, within breeds, individual dogs weighing at or above the mean bodyweight for their breed/sex were at 1.25 times risk compared with dogs weighing under the mean. And finally, older dogs showed much higher risk of KCS. Compared with dogs aged under 3 years, dogs aged 6 to 9 years had 11.3 times risk and dogs aged over 12 years had 29.4 times risk.

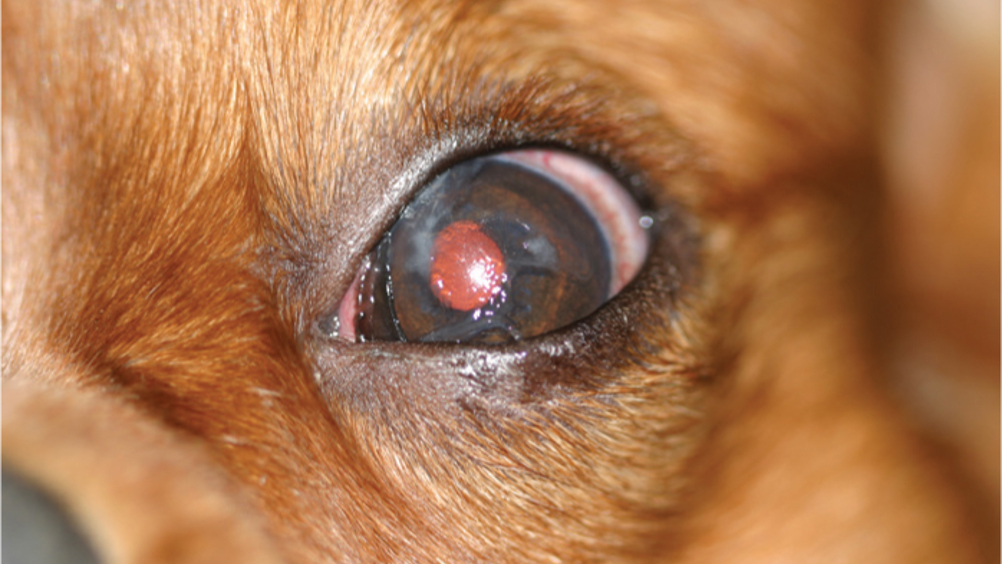

KCS is an unpleasant disorder for affected dogs and can lead to long-term issues such as corneal ulceration, blindness or even eye rupture if not detected and managed early. The veterinary nurse can play a key role by alerting owners of predisposed breeds (e.g. American Cocker Spaniels), types of dogs (e.g. brachycephalic breeds) or demographics (e.g. older dogs or overweight dogs) to monitor for signs of dry lusterless corneas, sticky mucoid eye discharge or eye discomfort. If diagnosed early, KCS can be effectively managed, although many animals will need lifetime treatment. Veterinary nurses can promote prevention of KCS by advising anyone thinking of purchasing a brachycephalic puppy to ‘stop and think before buying a flat-faced dog’.