A student veterinary nurse (SVN) is defined within the Veterinary Surgeons Act (1966), Schedule 3, as a person enrolled, under the registration rules, with the RCVS for the purpose of undergoing training as a veterinary nurse at an approved training centre or an approved veterinary practice (Kissick and Hockey, 2015). Branscombe (2012) highlighted how within Schedule 3 there are safeguards in place to enable veterinary surgeons (VS) and registered veterinary nurses (RVNs) to train SVNs. These include permitting a SVN that is employed or on a placement in a training practice to give medical treatments to an animal under their supervision. Within a veterinary context, the meaning of ‘direction’ is understood to be when the VS instructs the person (RVN or SVN) as to the activity but is not necessarily present. Whereas, ‘supervision’ is when the VS or RVN is present on the premises and is able to assist if required (Kissick and Hockey, 2015). Under the Veterinary Surgeons Act (1966), Schedule 3, a SVN should be supervised by a VS or RVN when performing medical treatments, or should, at the least, ensure that there is a VS or RVN on the premises, available to assist the SVN if needed. This differs from human nursing where all student nurses are only permitted to administer medications when under the personal supervision of an authorised person, such as a registered nurse (Reid-Searl et al, 2008). It is important to note that if an RVN is supervising a SVN this is done so under the direction of a VS and any minor surgery, such as suturing, must be done under constant, direct and personal supervision from the VS (Pullen et al, 2011; Branscombe, 2012) (Figure 1). However, as with human nursing, it could be argued that the requirement of SVNs working lone shifts or carrying out procedures without supervision occurs mainly when VS and RVNs are busy (Reid-Searl et al, 2008). The ethical implications that may be encountered regarding SVNs working outside the realms of Schedule 3 are outlined below.

Veterinary nursing and ethics

According to Rollin (2006) ethics are a set of rules or standards that govern the conduct of a person or persons who are members of a profession or culture. They include the reasons behind professional opinions when encountering moral questions and examine whether the notions were appropriate or inappropriate. RVNs also need to be able to make decisions effectively by understanding the issues related to any questions. With this RVNs and SVNs should be able to act in a way that takes into account both personal and professional ethical values (Pullen et al, 2011). Crump (2013) described veterinary ethics as being specifically concerned with all aspects of animal rights and welfare and how these are applied to the Codes of Professional Conduct for VS and RVNs. SVNs who work alone could be accused of not considering these as they are often performing tasks they are not fully trained to do. Veterinary ethics also bring about debates within the profession that assist in resolving issues that impact on everyday practice, such as allowing SVNs to work lone shifts. However, these may result in conflicting ethical values such as allowing SVNs to work lone shifts when staffing levels are low (Crump, 2013).

Veterinary nursing and the law

The veterinary nursing profession is constantly evolving and with the recent introduction of the Royal Charter on the 17th February 2015, the whole of veterinary nursing profession within the UK is regulated (RCVS, 2015). With this comes the creation of one Register, meaning RVNs or SVNs enrolled with the RCVS will be allowed to undertake veterinary activities allowed under Schedule 3 of the Veterinary Surgeons Acts 1966 (Orpet, 2015). The presence of a Register for veterinary nurses is important for a number of reasons — it affects the way the general public views veterinary nursing, as it demonstrates to them that the people taking care of their animals are responsible and accountable for their actions, and it illustrates that they have undertaken a rigorous training course (Harvey et al, 2014). The Code of Professional Conduct (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2015) states that it is compulsory for RVNs to maintain their standards and update clinical knowledge by undertaking continual professional development. Furthermore, the Code of Professional Conduct (2015) highlights that RVNs are accountable for their actions and that they accept that if found guilty of professional misconduct they will be accountable and disciplined by a committee (Orpet, 2015).

Pullen et al (2011) highlighted that along with responsibility and professional accountability RVNs are accountable to the law for their actions and must decide if any action taken will break the law. This too, applies to SVNs, therefore any SVN asked to work alone should be familiar with relevant legislation and decide whether their action would be in breach of this and subsequently whether they would be breaking the law (Pullen et al, 2011). RVNs and SVNs need to be aware that there are two types of law that may be encountered within the veterinary profession.

Criminal law, according to Grey and Wilson (2006), is concerned with offences that are punishable by the state and are governed by parliamentary acts with the sole intention to protect both society and individuals from harm. RVNs or SVNs could be involved in criminal cases if they are prosecuted for not obeying the law by acting outside the realms of Schedule 3 of the 1966 Veterinary Surgeons Act, such as a SVN administering intravenous medication when working alone without constant direct supervision (Abbitt, 2011; Pullen et al, 2011). Potential consequences of a SVN breaking a criminal law, having a criminal record or being deemed not fit for practice could include removal from the Register by the RCVS.

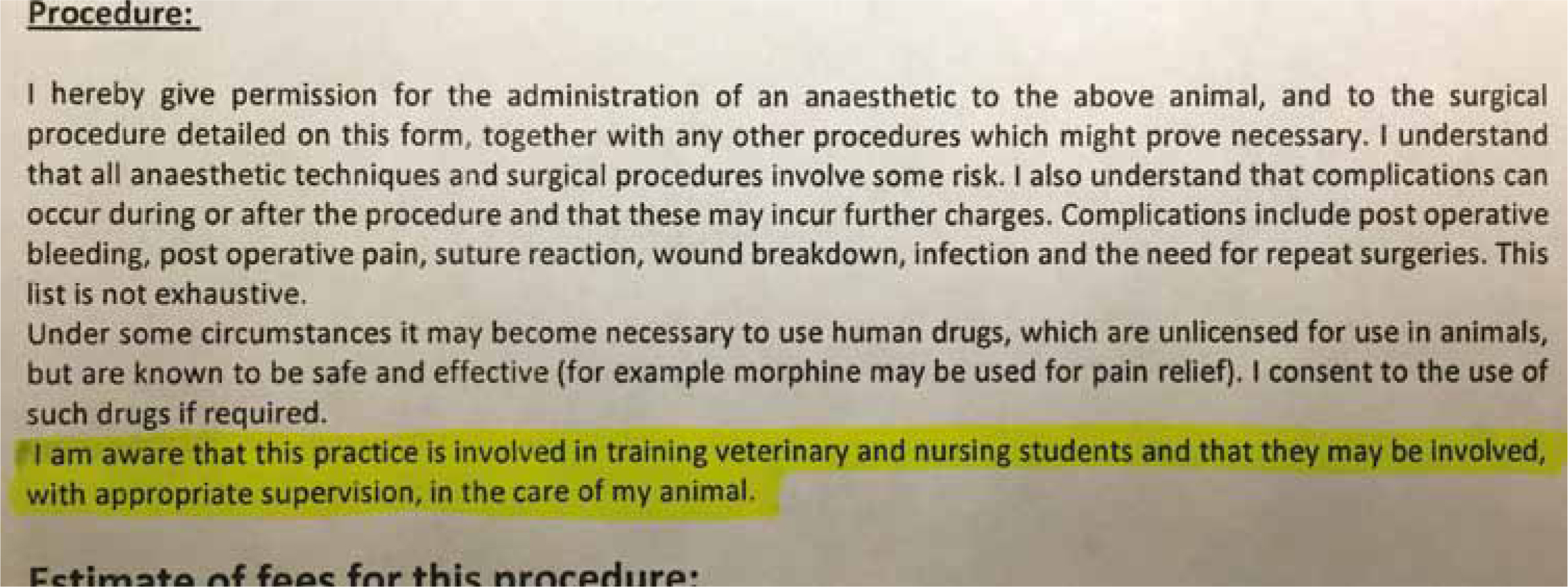

Civil law is concerned with a loss or harm suffered by an individual due to crime or a failure to fulfil obligations with regards to another person (Abbitt, 2011). Civil law is most applicable to veterinary medicine when there has been a breach of contract or negligence (Grey and Wilson, 2006). Grey and Wilson (2006) explained how a breach of contract can occur when the terms of a contract have not been fulfilled, for example an animal receiving treatment for which permission was not gained or an incorrect surgical procedure being performed. It could be argued that a breach of contract could occur if the owner signs for consent to treatment, but is not informed that a SVN would provide treatment to their animal, consequently the owner would be unable to make an informed decision to leave their animal in the care of a SVN and subsequently provide informed consent (Dye, 2006) (Figure 2). Therefore, this contravenes the Code of Professional Conduct (2015) where it is highlighted that a client must be informed if any procedure is to be performed by a SVN (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2015). This too, would be applicable to situations where SVNs will be the sole carer of a patient overnight, when information on the care of patients, including who is providing the care, should be stipulated to the owners (Canning, 2012).

RVNs and SVNs have a duty in law to not cause harm or loss to clients. This can be further described as, preventing a tort (a civil wrong) that is a wrong against someone's possessions, reputation or personal safety (Grey and Wilson, 2006). RVNs and SVNs have a responsibility to provide a duty of care to clients, colleagues and the practice, however, they have no legal duty of care to the animal as the law classes them as chattels and does not acknowledge that the damage or loss of chattels causes distress to owners (Earle, 2006; Abbitt, 2011). The RCVS expects nurses to consider the ethical issues surrounding a patient's welfare and work towards avoiding gross misconduct. This may be through assessing their own personal scope for competence in performing tasks directed by the VS and being mindful that incompetent actions run the risk of gross misconduct (Earle, 2006).

To avoid gross misconduct and provide appropriate care to patients the RCVS (2015) stated that all nurses must comply with appropriate legislation, such as the Animal Welfare Act (2006). This Act of Parliament enforces duty of care on pet owner's to provide correct animal welfare under the five freedoms, that must be adhered to by all people who are responsible for an animal including VS, RVNs and SVNs. Any breach of the five freedoms would be viewed as gross misconduct. An ethical problem may arise if an animal was in pain and required intravenous analgesia and a SVN was in practice alone and subsequently not under constant direct veterinary supervision. The SVN has a duty of care to the client to provide analgesia, however if they were to administer the medication this could be viewed as gross misconduct. Therefore, the VS has a duty of care to the SVN to ensure that they are not left in a position that could jeopardise their professionalism. In particular, if a problem arose, even if the SVN is competent in the task they are not qualified to perform it independently. Conversely, some may argue that if a SVN does not provide the analgesia they would be negligent and in breach of the Animal Welfare Act, as they would not be providing freedom from pain for the animal. Mann (2013) clearly stated that a RVN or SVN should not act in a way that would be construed as unlawful even if they believed it was ethically correct, as this does not make it lawful. Similar situations are encountered within human nursing, as many student nurses understand that they must be under direct supervision when administering medication; however, they are sometimes left to perform such tasks alone in order to keep in favour with the registered nurses, thus, not only resulting in an internal ethical conflict but also the breaking of law (Reid-Searl and Happell, 2012).

Delegation to SVNs

Branscombe (2012) highlighted when delegating to SVNs it is the VS and RVNs who are responsible for ensuring that the SVN is competent in performing tasks required, and that the SVNs only undertake work that they are legally allowed to do. Within human nursing, it is also emphasised that a registered nurse is professionally accountable for patient care and that it must be ensured that a student nurse administering medication has the adequate knowledge and experience to do so (Reid-Sear et al, 2008; Reid-Searl and Happell, 2012). It could be argued that the above is not taken into consideration when asking an SVN to work lone shifts as they are not legally allowed to perform Schedule 3 tasks without the supervision of a VS or RVN. SVNs might find it challenging to recognise their limitations and admit when they are not competent to undertake certain work. SVNs may also feel compromised if they refuse to perform such tasks (Pullen et al, 2011).

Arguably there are potential exceptions to SVNs performing tasks without veterinary supervision, these include being directed by the VS to administer uncomplicated oral medications or subcutaneous injections (Branscombe, 2012). Exceptions may be given to these as VS often direct owners to perform such tasks and it can be assumed that a SVN would also be qualified to carry out these basic tasks. However, Branscombe (2012) and Kissick and Hockey (2015) stated that administering intramuscular and intravenous injections or invasive procedures, such as the placement of intravenous catheters, should not be carried out without veterinary supervision. Therefore, any SVN working a lone shift and required to perform such tasks is in breach of the Code of Professional Conduct (2015) as well as not abiding by the Veterinary Surgeons Act (1966), and consequently breaking a criminal law.

Conversely, Mann (2013) stated that within the Code of Professional Conduct (2015) both RVNs and SVNs should make animal welfare their primary concern and should not undertake any actions which they do not feel competent to do, or have the necessary skills to complete, as this may put the animal's welfare at risk. However, under the same heading it is stated that RVNs and SVNs should not cause a patient unnecessary suffering by failing to assist in the provision of adequate pain relief (Mann, 2013). It could be argued, that the provision of analgesia would cause the least harm for the greatest good and would be supported by utilitarianism, a consequentialism branch of ethics. This ethical school of thought believes that the outcome of an action determines whether it is right or wrong and is deemed to be right if the greatest good, for the greatest number of individuals is achieved (Pullen et al, 2011).

Consequently, it may be argued that if an SVN working alone is to follow the Code of Professional Conduct (2015) and provide analgesia even without veterinary supervision it should be provided by subcutaneous injection, rather than intramuscular or intravenous, in order to fall within the laws of the Veterinary Surgeons Act (1966). The provision of analgesia in this way would be supported by deontology, a non-consequentialism branch of ethics, which refers to the ability to ensure that a person's decisions are based on what is deemed ‘the right thing to do’ regardless of the consequences (Budd, 2012). However, deontology would not support a SVN working alone as they would be more likely to perform tasks beyond their limitations, thus disregarding the RCVS Code of Professional Conduct (2015) and would therefore imply that if the SVN disregards the Code of Professional Conduct once, they will continue to do so, ignoring the consequences of their actions (Wood, 2011).

Canning (2012) argued that negligence of patients or necessary disciplinary action might be a consequence if a SVN or RVN chose to follow one school of thought over another. Both ethical and professional implications should be taken into account when considering the best course of action, and if a SVN is unsure of what they should be doing then they should seek clarification from a RVN, VS or the RCVS Code of Professional Conduct (2015) (Canning, 2012).

Resolution

The regulation and monitoring of veterinary practices using SVNs to work lone shifts requires compliance from all bodies within the veterinary profession and alternatives should be encouraged. Ignorance of the Code of professional Conduct (2015) and Veterinary Surgeons Act (1966) is not to be accepted as an excuse for using SVNs to work lone shifts, as RVNs and SVNs should be constantly reminded that they are accountable for their actions (Webb et al, 2013). Making RVNs and SVNs aware of the laws that are applicable to them when training could aid in reducing the request for SVNs to work lone shifts, however this could be difficult to govern (Abbit, 2011). Another solution would be for practices to employ locum RVNs to cover the lone shifts, or if an SVN is required to work weekend or night shifts to gain experience then a RVN should work alongside them so they are under constant personal supervision, as within human nursing (Reid-Searl et al, 2008).

Conclusion

As the demand to supply RVNs increases the veterinary profession must be aware that SVNs are not adequate substitutes for qualified veterinary nurses. It is often taken for granted that SVNs willingly act as substitutes to gain further experience and consequently employers overlook the ethical implications involved. However, due to their trainee status, they do not possess the necessary skills, knowledge nor expertise to perform the same tasks required of a RVN. Therefore, the profession must seek out alternative methods to fulfil unsociable roles, such as working alone, so as not to place undue pressure on SVNs to partake in activities that may be deemed illegal.