The Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) defines continuing professional development (CPD) as ‘the systematic maintenance, improvement and broadening of knowledge and skills and the development of personal qualities necessary for the execution of professional and technical duties throughout a veterinary nurse's working life (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2010a).

A process of lifelong learning, engagement in CPD is commonly acknowledged to:

CPD is, therefore, important for veterinary nurses.

In comparison with continuing education, CPD may be considered as an ‘improved alternative’ (Konkol, 2005, p7o), offering a more structured yet broad and flexible approach to continuing education. The concept of self-directed learning is based around the adult learning theory and is closely linked to experiential learning (learning by doing). Autonomy features highly in this educational process with an emphasis being placed on personal identification of learner needs. Comparable with the notion of CPD, an experiential cycle is a cyclical process based on the premise that concepts are nonpermanent, developing and transforming over time. Kolb's (1984) theory of experiential learning represents four stages of learning (concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization and active experimentation) and is a useful model by which practitioners can develop their practice.

CPD and the regulated veterinary nurse

The RCVS Veterinary Nurses' Council introduced a non-statutory register for veterinary nurses in 2007. With this came the additional responsibilities associated with professional regulation. As members of a self-regulating profession, veterinary nurses in the UK are expected to be accountable for their actions and adhere to their own code of conduct, the Guide to Professional Conduct for Veterinary Nurses (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2010b). The guide reflects the moral and ethical standards that registered veterinary nurses (RVNs) are expected to follow and sets these out in part one of the guide as the ‘ten guiding principles’. Also listed in detail are the responsibilities of a veterinary nurse, one of which makes reference to the requirement for nurses to maintain their competence by completing CPD.

In support of this guidance RVNs need to undertake a minimum of 6 days (45 hours) of CPD over a period of 3 years to satisfy the regulatory requirements. The CPD completed must be effective and of direct relevance to the role in which the veterinary nurse works. A CPD record card is issued to each RVN on an annual basis by the RCVS and also provides guidance on the different methods by which CPD can be completed.

This record should be accurately maintained as a number of record cards will be randomly audited each year by the RCVS Veterinary Nursing department.

‘Veterinary nurses must continue their professional education by keeping up to date with the general developments in veterinary nursing, particularly in their area of professional activity and must maintain a record of continuing professional development (CPD) undertaken as evidence of so doing.’

The CPD record cards of RVNs will also be checked during inspections of practices made under the RCVS Practice Standards Scheme. Veterinary nurses are generally keen to refresh their knowledge and learn new skills; the first audit of CPD records by the RCVS in 2009 indicated that veterinary nurses are completing in excess of their annual CPD requirement. The audit sampled approximately 10% of RVNs who had been qualified for 3 years or more and demonstrated that nurses completed an average of 23 hours CPD in 2007 and 28 hours in 2008 (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2009). Although completion of CPD is an obligatory requirement of regulation in the UK, veterinary nurses are unlikely to be disciplined for non compliance; however this would be taken into account if a complaint of misconduct was made against a RVN.

Forms of CPD

Consideration of individual training and development needs is essential; once these requirements have been highlighted some time should be taken to plan the best method of fulfilling them. CPD is available in a variety of formats but should be selected to suit the individual's needs and learning style rather than in an ad hoc fashion.

CPD can be achieved by one or all of the following methods:

Identifying, planning and undertaking CPD

There are two types of knowledge; procedural or practical knowledge and declarative or higher-order knowledge. The former is associated with carrying out a task or performing a skill, whereas the latter concerns the acquisition of facts. Professional work necessitates both types, the diversity of which demands a varied educational approach and utilization of a range of learning methods. As Oakley et al (2004, p20) states, ‘No instructional method will work well for all learners’, therefore personal learning style and preferred modes of delivery should be contemplated when selecting and undertaking CPD.

Within literature, the most effective forms of CPD include learning that is linked to one's area of work, interactive modes of delivery and strategies that involve multiple educational interventions (Cantillon and Jones, 1999). Regardless of the capacity in which the veterinary nurse qualification is utilized, consideration must be given to the nature of the work that is currently being undertaken. It is sensible to select topics to study that are relevant to one's job role, yet it is important to venture outside of one's ‘comfort zone’ from time to time, learning about novel topics in addition to those that are favoured or are considered to be more familiar.

Needs assessment is an essential foundation on which to plan and organize CPD. Identifying individual strengths and weaknesses is cited as a fundamental yet challenging part of this process (Gibbs et al, 2005; Konkol, 2005). Research has traditionally highlighted a poor correlation between practitioners' self assessment of their knowledge and subsequent performance in a particular field (Tracey et al, 1997). Thus identification of individual needs should be based on evidence from a range of sources, including colleagues.

It is well documented that CPD must be cost effective to avoid wasting resources (Brown et al, 2002). Regardless of type, most CPD activities will require funding, the exact amount varying according to provider, duration and mode of delivery. Securing the funds and time required to attend CPD can prove problematic for employees. Yet this can be overcome by emphasizing the value in keeping up to date with current developments and the requirement for veterinary nurses to modernize their knowledge and skills.

The role of reflection in effective CPD

Once qualified, the competence of veterinary nurses is periodically monitored and measured through the amount and quality of CPD that is undertaken. A key concept of CPD is the relationship between knowledge and competence, however, simply engaging in CPD does not guarantee competence.

Associated with experiential learning, reflective practice is integral to the learning process and has long been viewed as an important strategy for health professionals (Burns and Bulman, 2000). Through reflection, professionals are encouraged to manage the indeterminate (uncertain) zones of practice, interpreting experiences and applying previous knowledge to new situations. For example, the application of existing knowledge, skills or techniques may not be adequate in preparing a veterinary nurse for the management of an atypical situation. However, the application of intuitive or reflective knowledge can help to create novel insights, promoting agreement about the necessary action.

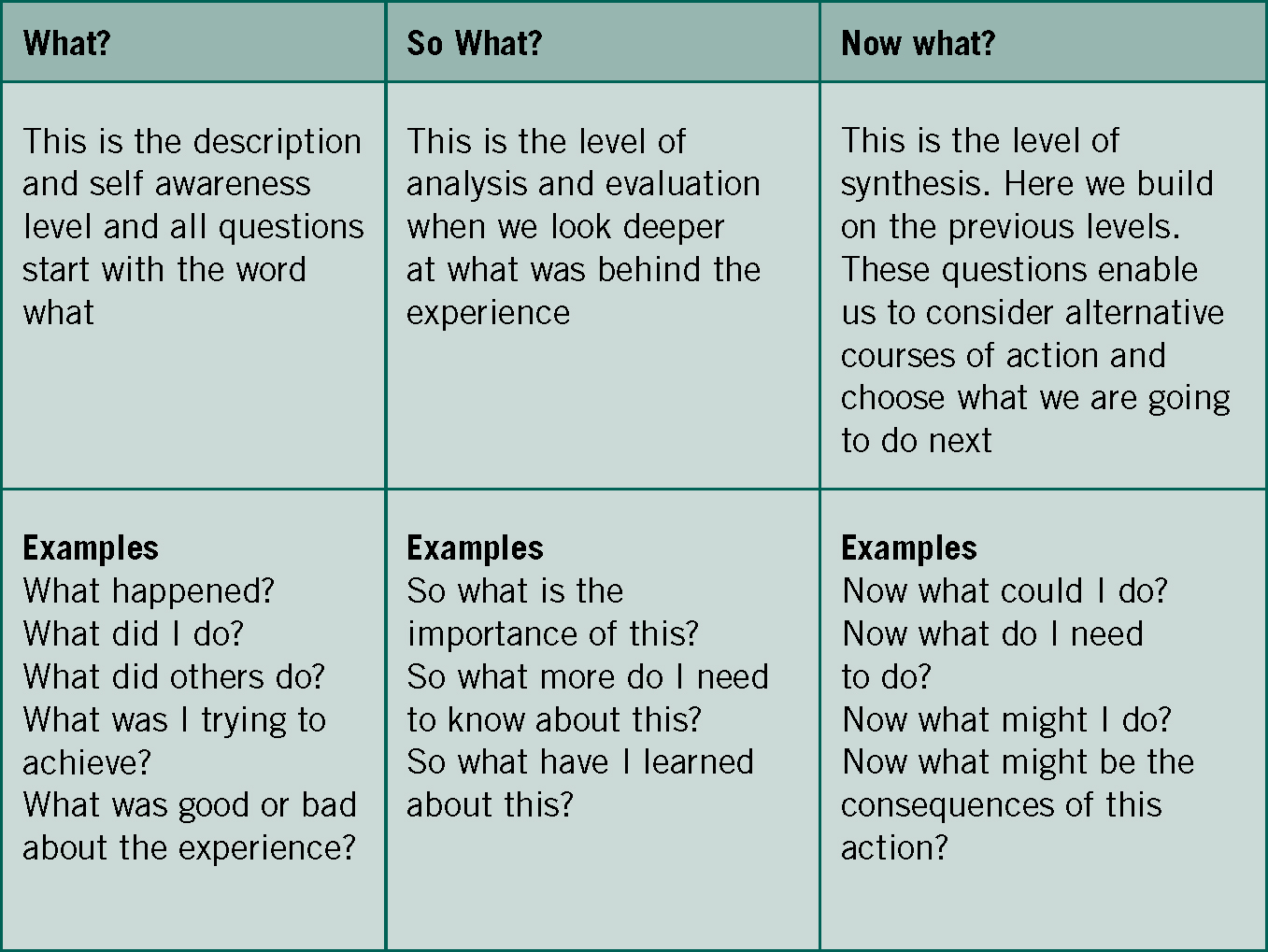

There are many reflective models available; two frequently referred to include Rolfe et al's (2001) Framework for Reflective Practice, and Gibbs' (1988) model of reflection. Rolfe et al use three simple questions to reflect on a situation: ‘What, so what, and now what?’ and consider the final stage as the one that can make the greatest contribution to practice. The questions provided within this model help to guide the process of reflection, making it an ideal structure for those who are less familiar with reflective practice (Figure 1).

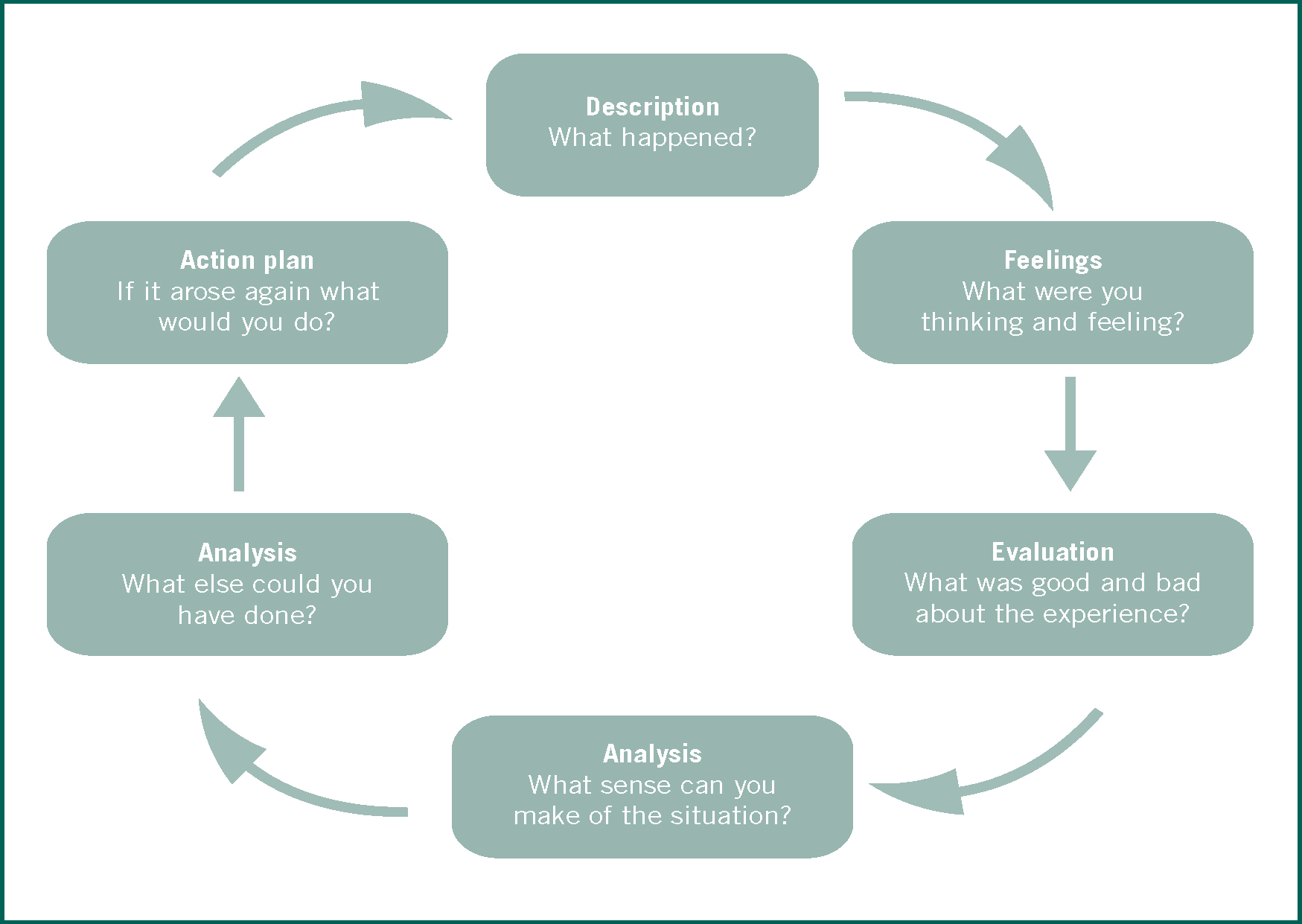

Similarly, Gibbs' (1988) reflective cycle is straightforward and encourages clear description of the situation and analysis of associated thoughts and feelings. An evaluation and review of the experience promotes the production of an action plan. This should detail how an action would differ if a similar experience arose in the future (Figure 2).

Effective implementation of change

Veterinary nurses with many years' post-qualification experience may consider themselves to be experts in their particular field, using practical, tacit knowledge and traditional protocols to guide their actions. While such intuitive experience is valuable, its lack of credibility and failure to consider the continual advances in veterinary medicine renders it inadequate as a sole means to inform practice and implement change.

Reviewing and critiquing research enables veterinary nurses to make judgements and decisions in relation to how best to modify their own practice and apply the most appropriate nursing interventions. Consequently, evidence-based practice is imperative; however the integration of evidence-based changes into practice is frequently cited as a major challenge following the completion of CPD. Grol and Grimshaw (2003) identified that barriers to change can act at different levels (individual, team and organization), thus it is important to understand these and implement strategies to overcome them.

The transition from best evidence to best practice is recognized as a challenging process with passive educational activities acknowledged as being less likely to instigate changes in practice. A superior method identified by Davis et al (2003) is participating in interactive and continuous education that is based on individual needs. This requires preparation and organization. While individuals may be willing to modify their practice, the clinical environment is often less conducive to change. Dissemination of information combined with a collaborative, multi-professional approach to the development of clinical guidelines and protocols is acknowledged as surmounting barriers to the uptake of evidence.

Conclusion

Veterinary nurses have a personal responsibility to undertake CPD and there are a wide variety of educational approaches and activities available to satisfy this requirement. Whatever CPD is undertaken, it is essential that having completed it, the veterinary nurse reflects on what she has learned and shares this with colleagues. The CPD should be of value in enhancing practice and competence. In addition, it is essential to ensure that a CPD record card is completed. This can then be used to illustrate CPD participation and maintenance of professional learning.