Veterinary practitioners perfom ovariohysterectomies on a daily basis, as a method of population control, disease control (e.g. of mammary neoplasia) and for ease of management of the bitch within the family home. Surgeon skills improve with experience, lessening the surgical duration and decreasing incisional size. However, new techniques are reported, that offer alternatives to the traditional way of neutering dogs.

First described in human surgery, laparoscopy is increasingly commonly performed in veterinary species. This minimally invasive technique consists of introducing specialised equipment into the abdomen of the dog through small incisions. By insufflating gas inside the abdomen cavity, using a camera and a monitor, the veterinary surgeon can diagnose and treat many conditions surgically. This procedure offers many advantages over laparotomy, including reduced post-operative pain, decreased recovery time, less desiccation of exposed viscera, reduced postoperative infection and improved cosmesis (Devitt et al, 2005). Laparoscopy permits an excellent observation (Austin et al, 2003) of the genitourinary tract and other viscera with rapid exposure of the ovaries and uterus, limiting the risk of incomplete ovarian tissue resection. Nevertheless, there are a few elements that make laparoscopy less attractive for many practitioners:

Laparoscopic procedure

From the nursing point of view the position of the animal and the settings of the specific equipment (camera, light source, monitor and insufflator) are of particular interest. Patients are positioned in supine decubitus with the abdomen clipped and aseptically prepared as for a laparotomy. The head should be approximately 30° below the pelvis; this is known as a Trendelenburg position (Austin et al, 2003). The viscera will displace cranially, improving the access to the reproductive tract.

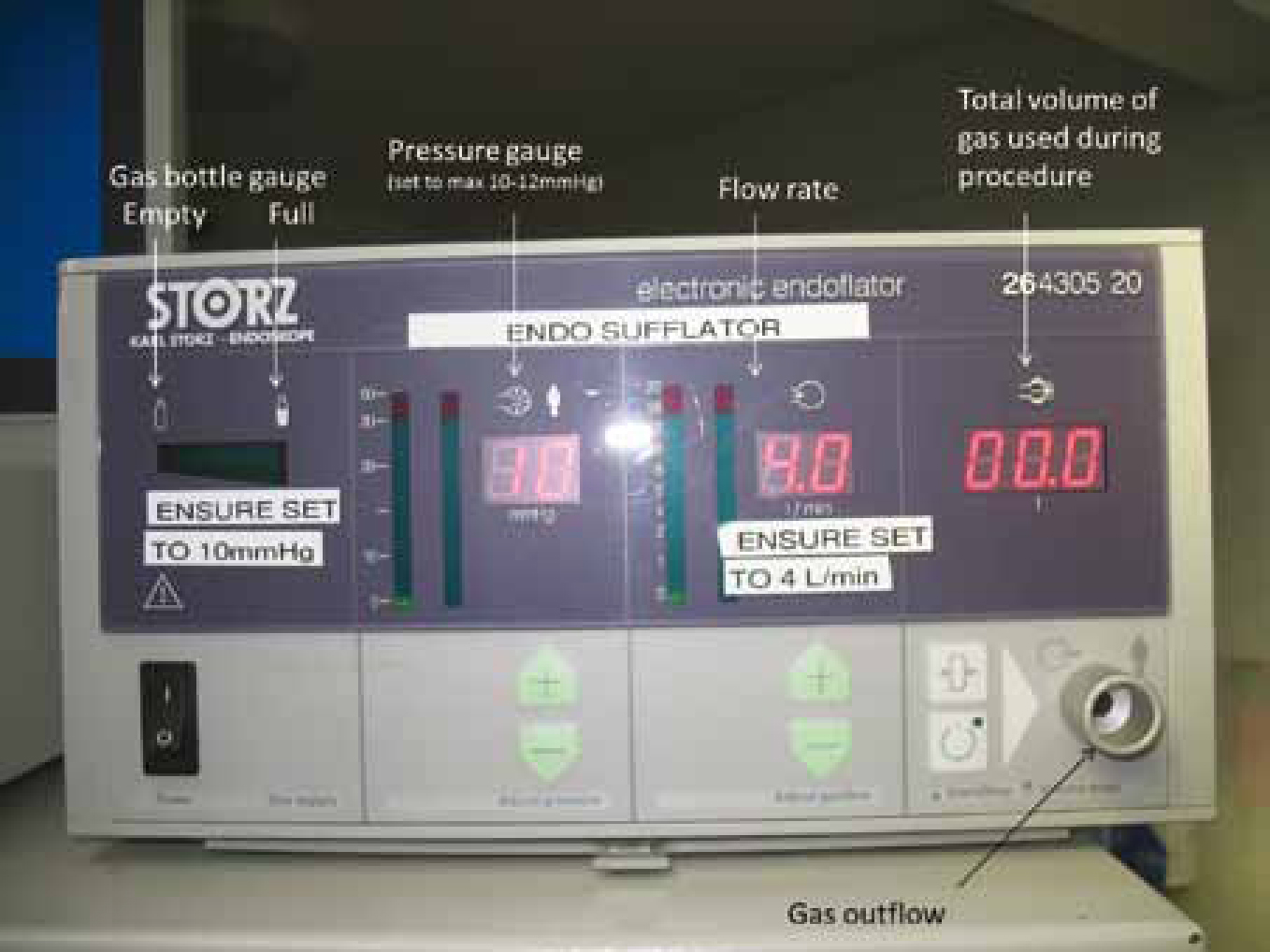

An adequate working space within the abdomen is necessary. For this purpose some gas is used and in order to achieve this, insufflation is performed using CO2 at 10–12 mmHg. CO2 is the best option because it does not support combustion, is rapidly cleared from the abdomen, and is less likely to form air emboli compared with other gases (such as oxygen or air) (Frederic et al, 2006). The mild positive pressure will aid in haemostasis, but higher pressures prevent diaphragmatic movement and hinder ventilation (Lhermette and Sobel, 2008).

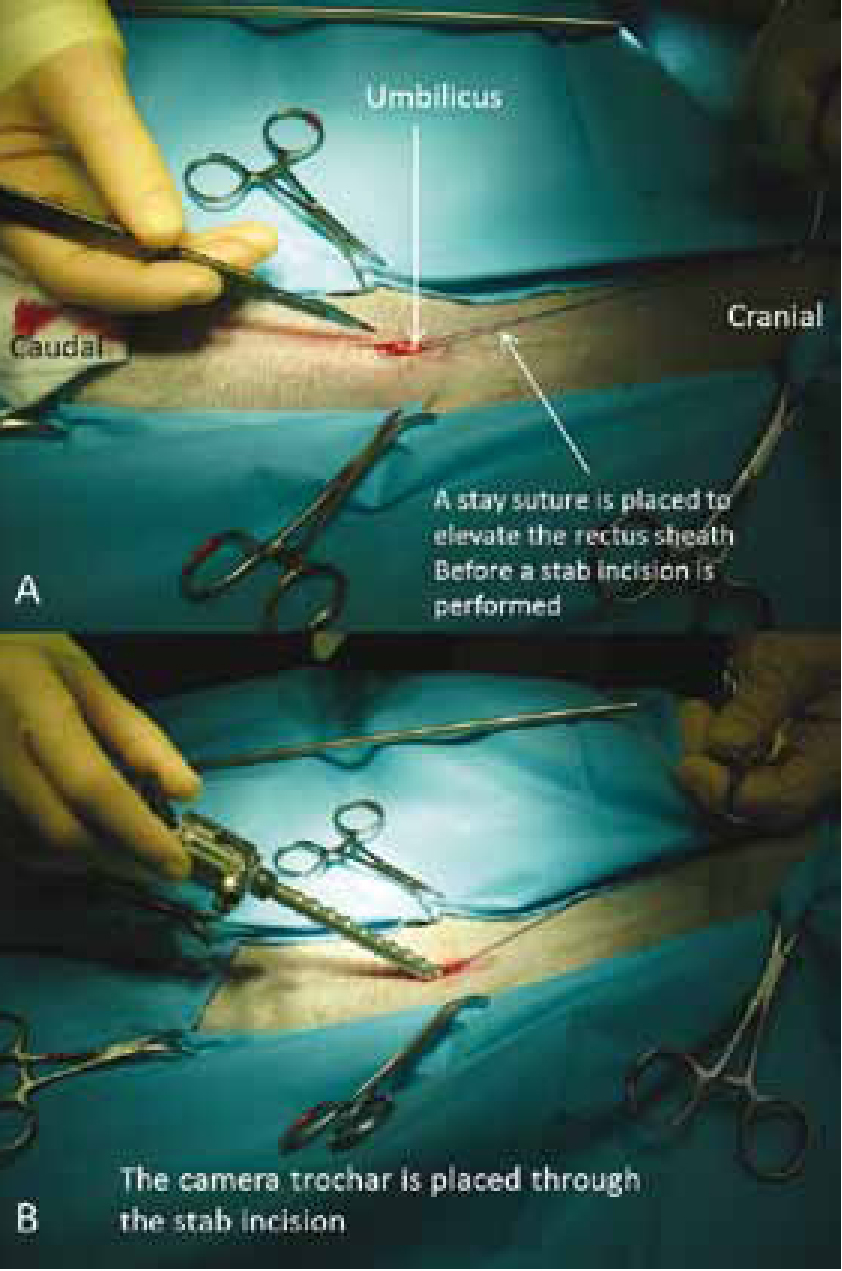

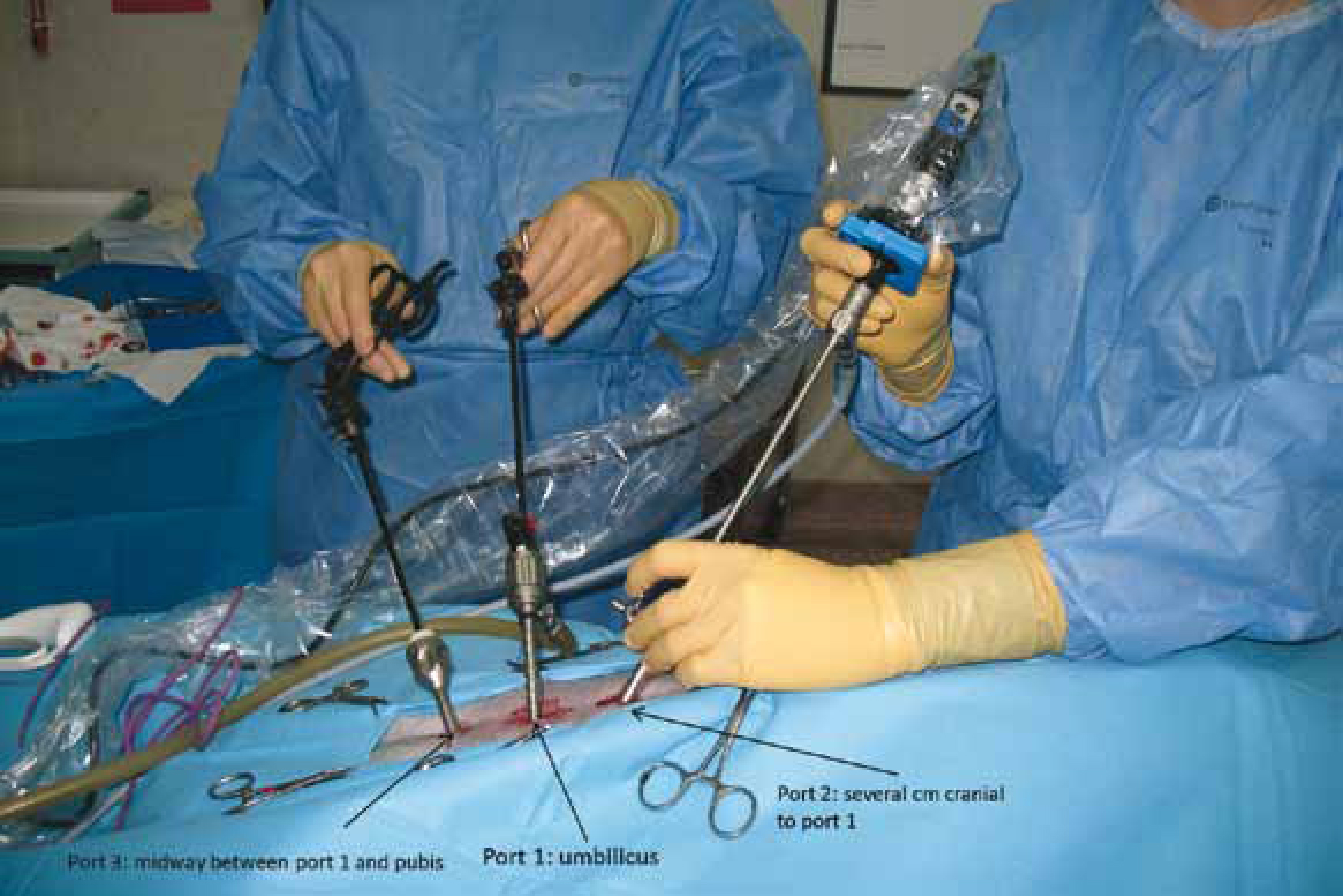

Insufflation can be achieved with two techniques: the Veress needle technique or the Hasson technique. The Veress needle is a spring loaded needle which is inserted blindly into the abdomen and permits insufflation through a smaller incision, but risks visceral laceration. The authors prefer the Hasson technique, which is a mini laparotomy, through which the camera portal is placed with reduced risk of visceral injury (Figure 2). Normally three ports are placed on the patient, one for the telescope (camera and light source) and two more for the instruments needed to perform the surgery (Figure 3). Depending on the surgeon, the surgical technique, previous experience, the presence of an assistant and the tools used, there are two main groups of portal positions for laparoscopic neutering:

Regardless of the technique, the operating portals should allow the veterinary surgeon to triangulate down to focus at the site of interest, they should be equidistant from the camera port and placed in non vascular areas. They are placed under visualisation with the telescope from inside the abdomen to avoid potential secondary complications.

Nurses should ensure that the operating theatre is well organised and spacious enough to work comfortably; special care must be taken to provide access to the laparoscopic light source, insufflator, anaesthetic monitoring equipment and the patient. Personnel must be aware that the CO2 gas cylinder may sometimes be replaced during the surgery and surgeons may decide to increase or decrease the pressure of the gas or the power of the light source. Also the anaesthetist must have space to reassess the patient any time during the surgery.

Once the patient is positioned and portals are placed, there are three neutering techniques possible:

Ovariectomies — these are less invasive and faster to perform than ovariohysterectomies. There is no benefit in removing the uterus during routine neutering in healthy female dogs: the occurrence of longterm urogenital problems, like pyometra or urinary incontinence, after ovariectomy is comparable to that after ovariohysterectomy (Goethem et al, 2006). Ovariectomy is performed by applying the use of a bipolar sealing and cutting device across the proper and suspensory ligaments of the ovarian pedicle. In order to improve visualisation of the ovaries, particularly during the learning curve, some surgeons like to tilt the bitch towards the right or the left depending on the ovary being removed such that the viscera falls, by gravity, away from the ovary. Alternatively, a traction external suture can be used. The ovaries are removed from one of the ports, CO2 evacuated from the abdomen and portal incisions closed routinely (Figure 4).

Laparoscopy ovariohysterectomy — this is very similar to the open technique. Once the suspensory ligament and ovarian vascular pedicle have been sealed and transected, the cervix is similarly addressed (Figure 5). Haemostasis can be performed in different ways: extracorporeal sutures, surgical wire ligatures, laparoscopic hemoclips, Yttrium Aluminum Garnet Laser, or bipolar vessel sealing devices (Davidson et al, 2004). The authors prefer to use bipolar sealing devices, which seal and transect without the need for instrument exchanges, reducing the surgical time. They are simple to use and the learning curve is shorter compared with extracorporeal knots, but they are expensive. Once haemostasis is achieved, the ovaries and uterus are removed from the abdominal cavity after enlargement of one of the caudal ports. The CO2 is evacuated and the abdomen closed routinely. The requirement to enlarge the portal negates the beneficial effect of the small portals with respect to decreased post-operative pain.

Laparoscopic assisted ovariohysterectomy — this is performed as for total laparoscopic ovariohis-terectomy (above), but the haemostasis and dissection of the body of the uterus is done in a standard fashion (transfixiant knots/millers knot with a reabsorbable suture material) after exteriorisation of the ovaries and right and left uterine horn through the caudal portal (i.e. the ovarian transection is intracorporeally; the cervical transection is extracorporeally). This means that the caudal portal must be enlarged as necessary prior to exteriorisation of the reproductive tract.

Anaesthetic considerations

One of the most severe complications of laparoscopy is gas embolism (Gharaibeh, 1998), which occurs if CO2 manages to enter the vascular space at any time of the surgery (most critical cases reported occurred at the beginning of the surgery) (Staffieri et al, 2007). To avoid anaesthetic complications and prevent risks, the pneumoperitoneum should never be greater than 15 mmHg (Frederic et al, 2006). Additionally, laparoscopic procedures entail changes in pulmonary function: lung volume is reduced, pulmonary compliance decreased and airway resistance increased secondary to increased intra-abdominal pressure and the patient positioning. For this reason, some anaesthetists prefer to ventilate patients with a positive pressure pneumoperitoneum. Additionally, CO2 is promptly absorbed by the peritoneum, causing hypercapnia and acidosis (Fukushima et al, 2011). For all these reasons comprehensive monitoring should be carried out during the anaesthesia, assessing electrocardiogram (ECG), oscilometric/Doppler blood pressure, pulse oxymetry, PCO2 and body temperature.

Other uses

Laparoscopy is also useful for diagnosis and treatment of ovarian remnants, uterine stump pyometra, fistulous tracts from inflammatory reactions to suture material or even pyometras (Minami et al, 1997; Lhermette and Sobel, 2008). Options in the male include treatment of abdominal cryptorchidism (the magnification makes this procedure very quick and easy) (Spinella et al, 2003; Miller et al, 2004) and sterilisation by occlusing the ductus deferents (Wildt et al, 1981).

Other considerations

Overall, laparoscopy offers a broad spectrum of possibilities for neutering bitches, offering improved cosmesis and reduced pain (Davidson et al, 2004; Devitt et al, 2005; Hancock et al, 2005). As with any other surgical technique there are some potential complications related to the procedure that can be minimised by paying special attention at the time when the portal incisions are made and at the end of the surgery when the surgeon is suturing the patient (Van Goethem et al, 2003). Reported complications of laparoscopy include: trocar injuries to the viscera, subcutaneous emphysema, visceral herniation, wound infection or haematoma formation at the trocar entry sites (Austin et al, 2003; Van Goethem et al, 2003; Davidson et al, 2004; Devitt et al, 2005; Mayhew and Brown, 2007).

Initial cost of the equipment is high, but depends on the type of endoscope and the devices used to provide haemostasis. The anaesthesia requirements are potentially more complicated for a laparoscopic procedure due to the abdominal insufflation and additional considerations should be identified prior to induction. As with all new techniques, the initial learning curve is steep, but should never be a disadvantage, because it is part of the veterinary profession's duty of care to continue learning and improving surgical skills. This is eventually to the benefit of the patient, with laparoscopy providing a faster recovery, with minimal visible scarring and decreased pain post operatively.

Conclusion

Despite investment costs and the initial difficulty in mastering techniques, laparoscopic neutering is optimal in bitches because of the potential advantages provided.