Feline injection site sarcomas (FISS) are tumours which arise in the site of injection in cats (Kliczkowska et al, 2015). Formerly they were known as vaccine associated sarcomas, given their association with vaccine administration. The link between vaccination and fibrosarcoma in cats was suggested for the first time in 1991 (Hendrick and Goldschmidt, 1991).

FISS are rare but aggressive tumours. They are locally invasive, with rapid growth. Necrosis and ulceration are commonly observed (Kang et al, 2016). Metastasis occurs in up to 28% of cases, with regional lymph nodes and lungs as the most commonly reported sites (Kang et al, 2016).

The latency period of FISS can be variable, ranging from 3 months to 10 years (McEntee and Page, 2001; Séguin, 2002). Such a large range of time can make it difficult to determine the true incidence of FISS (McEntee and Page, 2001; Martano et al, 2011). One recent epidemiologic study that evaluated only sarcomas associated with vaccine administration, determined the incidence of post-vaccination injection site sarcoma to be 0.63 sarcoma cases/10000 cats vaccinated and 0.32 sarcoma cases/10000 doses of all vaccines administered (Bowlt, 2015).

Aetiology

Inflammation has long been associated with the development of cancer, and cats are very prone to developing sarcomas associated with trauma and/or inflammation (Cannon, 2015). Besides FISS, ocular sarcomas are also associated with prior history of ocular trauma or chronic uveitis and bladder sarcomas are associated with chronic cystitis (Morrison, 2012).

In order to clarify the aetiology of FISS, several studies were undertaken. From these, the scientific community realised that vaccines played a causal role in the increase in the number of soft tissue sarcomas identified in cats during the 1990s (Kass et al, 2003). However, even without scientist consensus, several other agents are also being implicated in FISS aetiology, namely injectable materials (lufenuron, penicilin, metilprednisolone, meloxicam), nonabsorbable suture material and microchips (Kass et al, 2003; Daly et al, 2008; Martano et al, 2011; Munday et al, 2011; Srivastat et al, 2012). Wilcock and colleagues (2012), affirm that it is not possible to attribute FISS aethiology to these agents, because previous vaccination, in that same location, could not be ruled out. In addition, it is known that the administration of vaccines at colder temperatures seems to be associated with a higher risk of developing FISS (Martano et al, 2011), but the type of syringe used, massaging the area, intramuscular administration, as well as feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) status or other feline virus infection did not demonstrate any correlation (Martano et al, 2011). It is also important to be aware that the vaccine reaction is additive and that the likelihood of sarcoma development increases with the number of vaccines given simultaneously at the vaccine site (Séguin, 2014). Over vaccination should also be avoided (Scherk et al, 2013; Séguin, 2014; Day et al, 2016).

The most consensual hypothesis for FISS etiopathogenesis is that the inflammatory reaction that results from the injection leads to uncontrolled proliferation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that undergo malignant transformation in a subset of cats (McEnteen and Page, 2001; Séguin, 2002; Séguin, 2014; Day et al, 2016). In human medicine, there are several examples of inflammation-associated neoplasia, some directly associated with infectious agents (e.g. papillomavirus, hepatitis B and C viruses, Epstein-Barr virus, Helicobacter pylori) and others related to non-infectious causes of chronic inflammation (e.g. cigarette smoke, asbestos, silica and other environmental carcinogens) (Daly, 2008).

Most FISS are fibrosarcomas but other histological variants include myofibroblastic sarcoma, myxosarcoma, undifferentiated sarcoma, malignant fibroushistiocytoma and, more rarely, rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma (Shaw et al, 2009; Giudice et al, 2010; Cannon, 2015).

Clinical presentation

FISS are generally diagnosed in cats at a younger age (median, 8 years) than non-injection site sarcomas (median, 11 years) (Bowlt, 2015).

These tumours are usually firm and fixed to the underlying structures (including the dorsal spinous processes or scapulae), often with appreciable cords of tumour tissue radiating from them, and variable in size (Bowlt, 2015; Kliczkowska et al, 2015). They can be large at the time of presentation, mainly due to their rapid growth (Martano et al, 2011) but also because of their frequent interscapular location, which is not always easy to detect by owners in initial phases of development (Figure 1). The mass is usually not painful, solid and may be cystic (Kirpensteijn, 2006; Bowlt, 2015).

There is no breed, gender or age predisposition determined (Kliczkowska et al, 2015).

Diagnosis

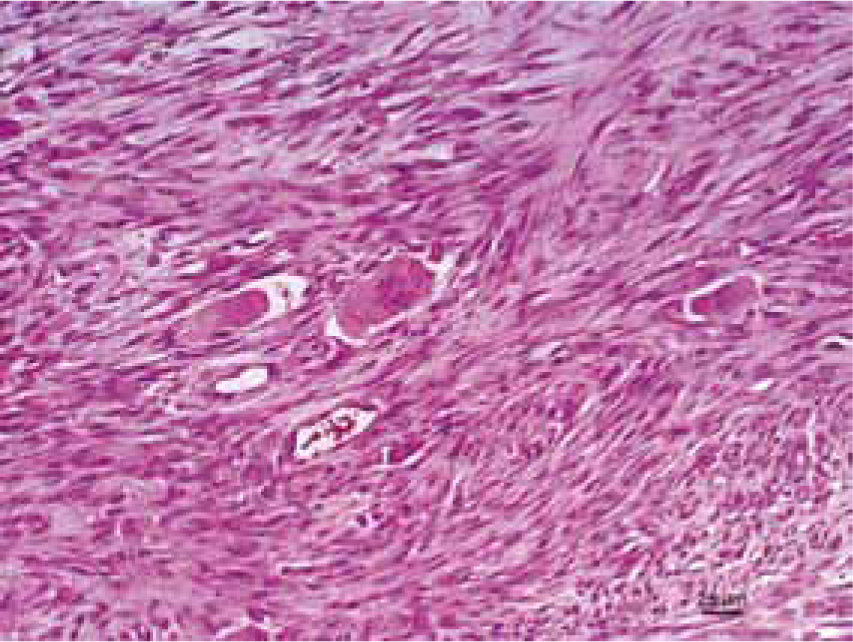

For a correct diagnosis, it is important to do a biopsy. A biopsy should be performed, if the mass has been present for more than 3 months, is larger than 2 cm in diameter, or is rapidly increasing in size, after recent vaccination. Histologically, and compared with sarcomas that are not associated with vaccination/injection, FISS are more commonly characterised by anaplasia, rapid growth, ulceration, necrosis and are often poorly encapsulated and infiltrate along fascial planes (Figure 2) (Hershey et al, 2000).

Cytology can also be performed, as an initial complementary examination, but according to the available data, cytology is reliable only in about 50% of FISS (Martano et al, 2011). The presence of neutrophils and marked cellular pleomorphism, are the main cytological characteristics (Kliczkowska et al, 2015). Additionally, a high sample cellularity with large nuclei, the presence of lymphocytes and macrophages, as well as mitotic figures and multinucleated neoplastic giant cells, can also be observed (Kliczkowska et al, 2015). All biopsies should be performed in such a way that subsequent surgical removal of the biopsy site and tract will not be hindered. It is also important to evaluate a minimum database, including a thorough physical examination, complete blood cell count, serum chemistry profile, urinalysis and evaluation of FeLV/FIV status. Thoracic radiographs, including ventrodorsal, right and left lateral views, and an abdominal ultrasound, should be obtained, to evaluate for potential metastasis (Séguin, 2002; Axiak, 2012). Regional lymph nodes should be evaluated through palpation, radiographs or ultrasonography and cytology, where applicable (Séguin, 2002). Advanced imaging techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging or contrast-enhanced computed tomography, are extremely useful for determining the extent of tumour invasion, as well as for assisting in treatment planning (Séguin, 2002; Novosad, 2003).

Treatment

Early identification of disease is the most important aspect for good therapeutic results (Axiak, 2012).

Effective treatment of FISS in cats is challenging. The truth is that an effective cure for FISS has not been found but it is now recognised that a multimodal approach, combining wide surgical excision, radiotherapy (both in a neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting) and chemotherapy, can lead to better results (Martano et al, 2011). Wide surgical excision of the primary tumour (Figure 3 and 4), meaning a margin of 3–5 cm of macroscopically healthy tissue and, at least, one facial plane beneath the tumour is fundamental, however, complete excision is often difficult and local recurrences are common.

Prognosis

The prognosis for recurrent or inoperable FISS is guarded to poor. When FISS is operable, the main goal is to perform a complete resection of the mass and obtain clean margins — this will greatly improve survival data and recurrence free interval (Hershey et al, 2000; Kirpensteijn, 2006; Giudice et al, 2010; Scarpa et al, 2012). Neoplastic cells often extend beyond the observable or palpable tumor mass, and clean margins of excision can only be determined by histologic examination. Microscopic assessment of surgical margins is an important prognostic factor for post-surgical monitoring and subsequent adjuvant treatment planning (Scarpa et al, 2012). Anatomic site also appears to be of prognostic value since, depending on the FISS location, surgical technique can result in wider or strait margins. Cats undergoing amputation for FISS on the limb did better than local excision anywhere else on the body (Hershey et al, 2000; Kirpensteijn, 2006).

The metastatic risk was originally assumed to be very low but, in fact, the risk probably increases with the survival time of the cat (Wilcock et al, 2012).

Prevention

It is now believed that FISS is associated with cats genetically predisposed, and although not a frequent disease, given its aetiology, it is very important to be informed and to be able to inform owners, in a correct way. First, the clients should be warned of the risk of vaccine/injection-associated sarcomas and the occurrence of local vaccine/injection reactions. The owner should be taught how to examine the injection site and seek veterinary assistance whenever necessary (Séguin, 2002).

For the veterinary team, it is important to record the location of each injection, type of vaccine, the manufacturer and serial number in the patient's notes. The location of the injection should be in an area that is amenable for eventual surgical removal. The subcutis of the abdominal wall well away from the spine and thorax, is a suitable location for injection, from a surgical standpoint. The locations that were recommended by the VaccineAssociated Feline Sarcoma Task Force (VAFST) created in 1996 (Morrison et al, 2001) to discuss this issue, were the distal part of the tail and the limbs which, although often difficult places to inject subcutaneously, should be chosen whenever possible. After vaccination or any other routine injection, all masses or inflammatory reactions should be closely monitored (Kirpensteijn, 2006; Carwardine et al, 2014).

As with all adverse reactions, the development of a vaccine-associated sarcoma should be reported to the relevant authorities in the country of residence (Bowlt, 2015).

Conclusion

FISS have become a very serious problem in daily veterinary practice. Veterinary oncologists are particularly familiar with this problem, since FISS accounts for over 40% of skin and subcutis neoplasms in cats (Kliczkowska et al, 2015). Although rare, FISS are tumours that can arise following injections. Since vaccines are the most common injection that cats receive, it is natural that cat owners may feel insecure about the benefits/damages of vaccines for their cats. It is important to communicate that avoiding vaccination can be even more dangerous and just as counterproductive. The diseases that vaccines are designed to prevent are not rare or without veterinary or human public health importance (rabies), and the agents that cause these diseases are themselves capable of resulting in epidemics (Kass et al, 2003). Knowing this, the next step is to alert owners (and be alert) to any mass/tumour arising in sites of previous injections (Kliczkowska et al, 2015). Owners are the ones who have closest contact with their pets, therefore client education is imperative in order to allow early detection of any abnormal sign of disease. Veterinary nurses, given their close relationship with animals and owners, are the veterinary health professionals with greatest ability to instruct owners in this issue.

The vaccination site, dose and other relevant information should be accurately recorded, in order to allow a complete medical history if necessary. Different vaccines should be injected in different anatomical places helping to reduce the inflammation level at the injection site. This information should be registered in clinical records, since it can allow an association between any lump that eventually arises with its probable cause (Séguin, 2014). Since it is not always possible to avoid FISS development, veterinary staff should, whenever possible, respect international recommendations for preferable injections sites in cats, which are right forelimb, below the right elbow for three-way vaccine panleukopenia + herpesvirus 1 + calicivirus; FeLV vaccines below the left stifle and rabies vaccines below the right stifle (Figure 5) (Scherk et al, 2013; Kliczkowska et al, 2015).

Any adverse reaction of vaccine should be reported to the manufacturer. If a FISS is histologically confirmed, it should also be reported to competent authorities from your country.

Key Points

Conflict of interest: none.