Lower airway disease, and specifically bronchial disease, is common in cats, and a cause of significant morbidity and even mortality. The predominant presenting sign is a chronic cough, which may be mistaken by owners for ‘furballs’, as the cat may retch during a coughing episode. Inflammatory bronchial disease is the most common lower airway disease in cats (Foster et al, 2004a), and is frequently termed ‘feline asthma’. However, feline asthma likely represents just one end of a spectrum of non-infectious, inflammatory, lower airway diseases seen in cats, with chronic bronchitis also associated with significant respiratory morbidity in this species. Veterinary nurses have an important role to play in the diagnosis of feline lower airway disease, and the emergency and chronic management of affected cats.

What is ‘asthma’?

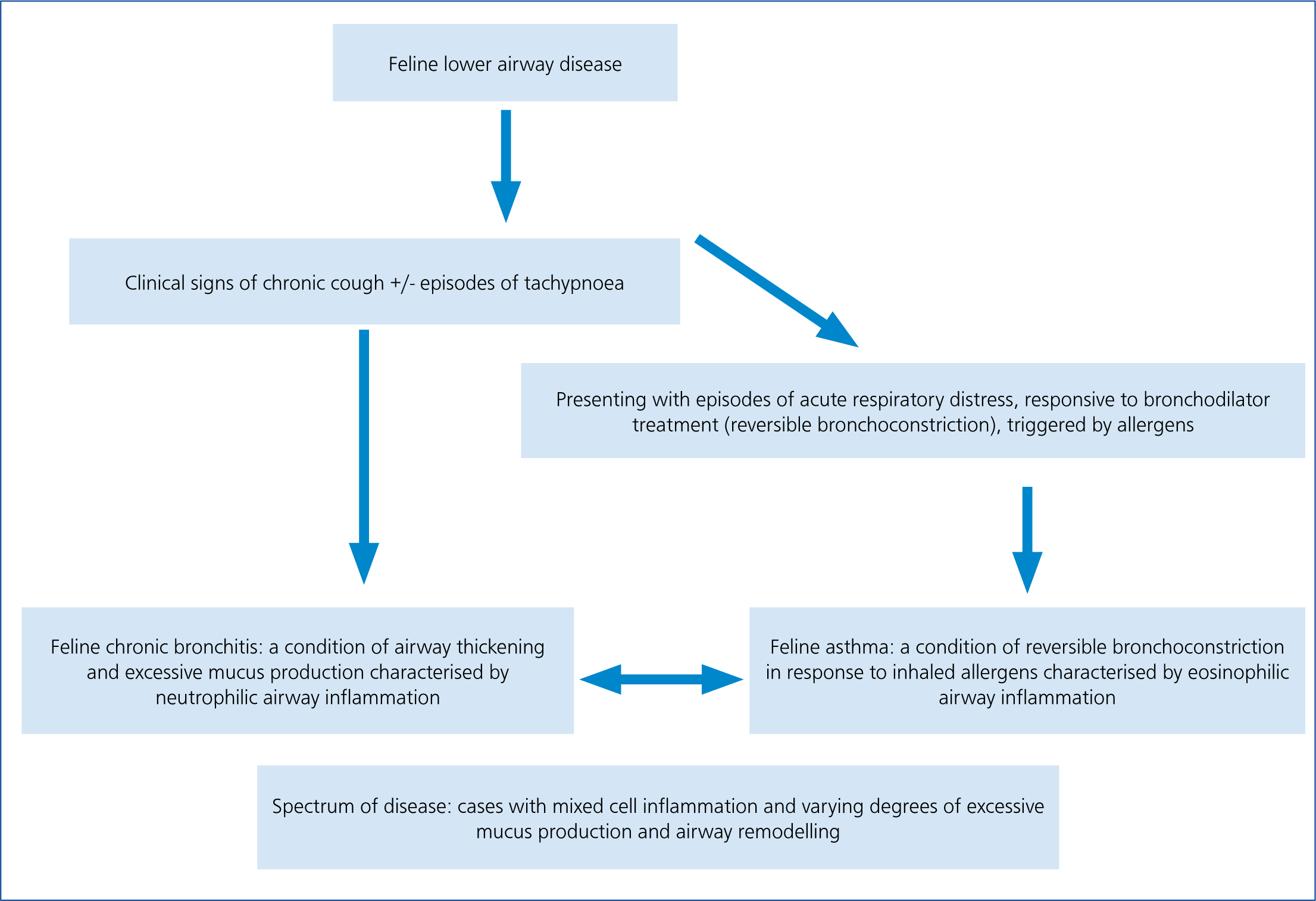

The term ‘asthma’ is used in human medicine to describe a condition caused by spontaneous bronchoconstriction and airway remodelling, often presenting with dyspnoea, and responding to treatment with bronchodilators (Reinero et al, 2009a). In cats, although a subset of patients will present in this way, the majority have a chronic cough. To complicate the classification of non-infectious, inflammatory bronchial disease in cats, many have predominantly neutrophilic airway inflammation, or a mixed cell cytology on bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). This is in contrast to the predominantly eosinophilic inflammation classically seen in feline asthma. Standardisation of terminology is not currently available and many consider non-infectious inflammatory bronchial disease in cats to be a spectrum (Rozanski, 2016), as illustrated in Figure 1, and in a clinical setting, without BAL, defining the underlying condition may not be possible.

Pathophysiology

In feline asthma it is generally accepted that a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction occurs within the airways, where sensitised cats react to repeat exposure to an antigen with mast cell degranulation. Histamine and leukotrienes result in increased vascular permeability and smooth muscle contraction (acute airway narrowing), eosinophils are recruited and worsen the inflammation and tissue damage (Corcoran et al, 1995). This inflammation results in airway hyper-reactivity, smooth muscle hypertrophy and excessive mucus production (Venema and Patterson, 2010). The condition is seen more commonly in young to middle-aged cats, with Siamese and other Oriental cats overrepresented (Foster at al, 2004b). Multiple triggering allergens are implicated, including dusty cat litter, house dust mites, strong chemical smells, building dust, perfumes, hairspray, cigarette smoke and pollens (Baral, 2012).

In chronic bronchitis neutrophilic inflammation predominates, with excessive mucus production and airway remodelling and narrowing. This condition does not seem to be acutely triggered by allergens or result in bronchoconstriction, but the causes are not fully understood (Venema and Patterson, 2010).

Reduced airflow occurs in both conditions due to oedema, mucus, inflammation and epithelial alterations, with bronchoconstriction occurring in cats with asthma. These changes in airway diameter, even if small, result in significant reductions in airflow. Over time changes become permanent including fibrosis and emphysema.

The role of mycoplasmas (small bacterial organisms) in feline respiratory disease has been studied in cats and remains unclear. The organisms are found as commensals in the upper respiratory tract, but have been associated with lower airway disease, where they may not be the primary cause, but are likely an exacerbating factor (Lee-Fowler, 2014). Testing for, and treating Mycoplasma spp. infection is therefore generally advised for cats with lower airway conditions.

Clinical signs of lower airway disease

Asthma and chronic bronchitis result in a chronic cough, due to airway narrowing, mucus, and direct effects of inflammation on mechanoreceptors in the airways. Owners may mistake this cough for a retch, or conclude something is stuck in the cat's throat, for example a hairball. Cats at the asthma end of this disease spectrum are more likely to develop respiratory distress and particularly expiratory dyspnoea, with increased effort on exhalation compared with inspiration. Exercise intolerance is hard to spot in cats compared with dogs, but affected cats may be lethargic, or become tachypnoeic after playing. Signs may be episodic, persistent or intermittent (Corcoran, 1995). On physical examination affected cats may have an expiratory wheeze or crackles, and if in respiratory distress they may be cyanotic.

Diagnosis

Importantly cats with lower airway disease can make fragile patients, decompensating and suffering a respiratory arrest if handled inappropriately. Although diagnostic tests are important, emergency treatment of dyspnoeic cats should be ‘hands off ’ and tests requiring restraint such as radiography postponed until the cat is more stable. Veterinary nurses play a vital role in the careful and calm handling of dyspnoeic cats to avoid deterioration.

Clinical signs and physical examination findings may be consistent with lower airway disease, but differential diagnoses such as congestive heart disease, lungworm, pleural space disease or upper respiratory disease must be excluded. Tests will be dictated by the individual case, but blood tests are generally unremarkable, with circulating eosinophils found in around 20% of cats with asthma (Rozanski, 2016). Faecal analysis may be indicated to exclude feline lungworm (Aelurostrongylus abstrusus).

Diagnostic imaging

Radiography is important in the diagnosis of lower airway disease and usually reveals a diffuse bronchial, or bronchointerstitial pattern (Figure 2) (Gadbois et al, 2009), although radiographs may be normal. Other abnormalities include lung hyperinflation, hyperlucency, right middle lung lobe collapse and aerophagia.

Thoracic computed tomography (CT) is growing in popularity in veterinary medicine and in cases of lower airway disease it can reveal airway thickening, lung lobe consolidation and mucus accumulation, and exclude other differential diagnoses (Figure 3).

Bronchoscopy and BAL

Bronchoscopy (Figure 4) with BAL is useful in the diagnosis of lower airway disease in cats, as collection of BAL samples allows cytology and testing for infectious agents to be performed. BAL samples can be collected via the bronchoscope, or blindly. Contraindications include severe dyspnoea/hypoxia, coagulopathy or cats with very unstable asthma. Bronchoscopy of asthmatic cats is associated with severe bronchospasm, but pre-treatment with terbutaline (a bronchodilator), and using saline at body temperature for the wash may help prevent this complication (Kirschvink et al, 2005).

Equipment for BAL

It is desirable to keep anaesthesia time to a minimum by preparing equipment before induction. Have available:

During the procedure the tube, or bronchoscope is passed distally to form a seal inside a bronchus and a wedge of lung isolated, before instilling the aliquots of sterile saline followed by aspiration. A frothy sample suggests surfactant and a successful BAL.

Anaesthetic monitoring

Monitoring under anaesthesia is commonly a nurse's job. Recording observations on an anaesthetic chart is important to identify trends and document the procedure. Monitor respiratory rate and pattern, oxygen saturation with a pulse oximeter, heart rate and temperature. If available an ‘elbow port’ (Veterinary Instrumentation) can be used to provide oxygen and a volatile anaesthetic agent during lavage. Saturation should be maintained at >95% throughout the procedure, and 100% oxygen supplied before, and immediately after samples have been taken for 3–5 minutes, and the cat closely observed for signs of hypoxia (shallow, rapid breathing, SpO2 < 95%) (Hibbert, 2013).

Complications also occur in the post-anaesthetic period when cats should be closely monitored for complications. Key points include:

Other complications can include pneumothorax and haemorrhage, thankfully rarely seen.

Sample handling

Ideally samples are analysed within 24 hours, which can be hard to achieve in general practice, so tubes may need refrigeration or smears preparing (Venema and Patterson, 2010). Discuss with the laboratory how to handle samples to maximise diagnostic yield. An EDTA sample should be collected for cytology, and an additional plain or EDTA sample submitted for Bordetella and Mycoplasma polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Interpretation of BAL results

Cytological examination in cats with lower airway disease reveals variable levels of inflammation, however results have to be interpreted with caution as normal cats may have up to 25% eosinophils in BAL samples (Baral, 2012). It has been suggested that cats with asthma will have higher total cell counts as well as elevated levels of eosinophils, whereas cats with chronic bronchitis show a predominance of neutrophils (Venema, 2010). Analysis of a BAL may also identify Aelurostrongylus larvae, intracellular bacteria and rarely, neoplastic cells.

Management of cats with lower airway disease

Emergency treatment

As mentioned, dyspnoeic cats are prone to decompensation so a ‘less is more’ approach should be adopted and thought given to stress reduction. Box 1 lists the appropriate approach to cases of feline lower respiratory disease presenting with dyspnoea. Note that other common causes of dyspnoea such as congestive heart failure and pleural effusion should be excluded.

Chronic therapy

The mainstay of treatment of lower airway disease is corticosteroid treatment, but bronchodilator therapy can be helpful for cats with bronchoconstriction. As treatment is life-long and potentially associated with side effects, other causes of airway disease should be excluded and treated empirically if necessary, such as antiparasitic treatment for lungworm. Clients should also be counselled as to maintaining their cat at a healthy weight and overweight or obese cats should be seen in a weightmanagement clinic at the practice to encourage slow, healthy weight loss.

Conclusions

Lower airway disease is common in cats and can be lifethreatening. Investigations include imaging and bronchoalveolar lavage. Management is based on the use of corticosteroids, but in inhaled form they are associated with fewer side effects. Bronchodilators, allergen avoidance and more recently therapies such as allergen specific immunotherapy may be other treatment options. The prognosis for cats with inflammatory lower airway disease is generally positive. Although life-long therapy is required, response to treatment is usually good. Deterioration or failure to respond should prompt reassessment of diagnosis, assessment of compliance, or a search for complicating factors such as infection. The veterinary nurse plays an important role in the care of affected cats, at initial presentation, during the investigation and crucially during treatment, when time spent with owners explaining and demonstrating the use of inhaled medication can make a great difference to compliance in the long term.