Although many species of flies occur in the UK, climate dictates that fly-borne transmission of parasites to pets is not important. Nonetheless, fly-borne diseases are migrating

Sensitization to bites

Mosquitoes and sandflies can sensitize pets with their saliva. They tend to bite around the muzzle, eyes, ear pinna, abdomen; the bite can be slightly painful but fleeting. It is not common to see flies biting. Once sensitized, there will be immediate wheal and flare reactions and/or delayed, reddish papules. Both will be pruritic for several days, and induce scratching, biting and self excoriation. The sandfly season is considered to be April to November; low level mosquito activity can continue through winter in some southern areas (Hnilica, 2011).

Sandflies

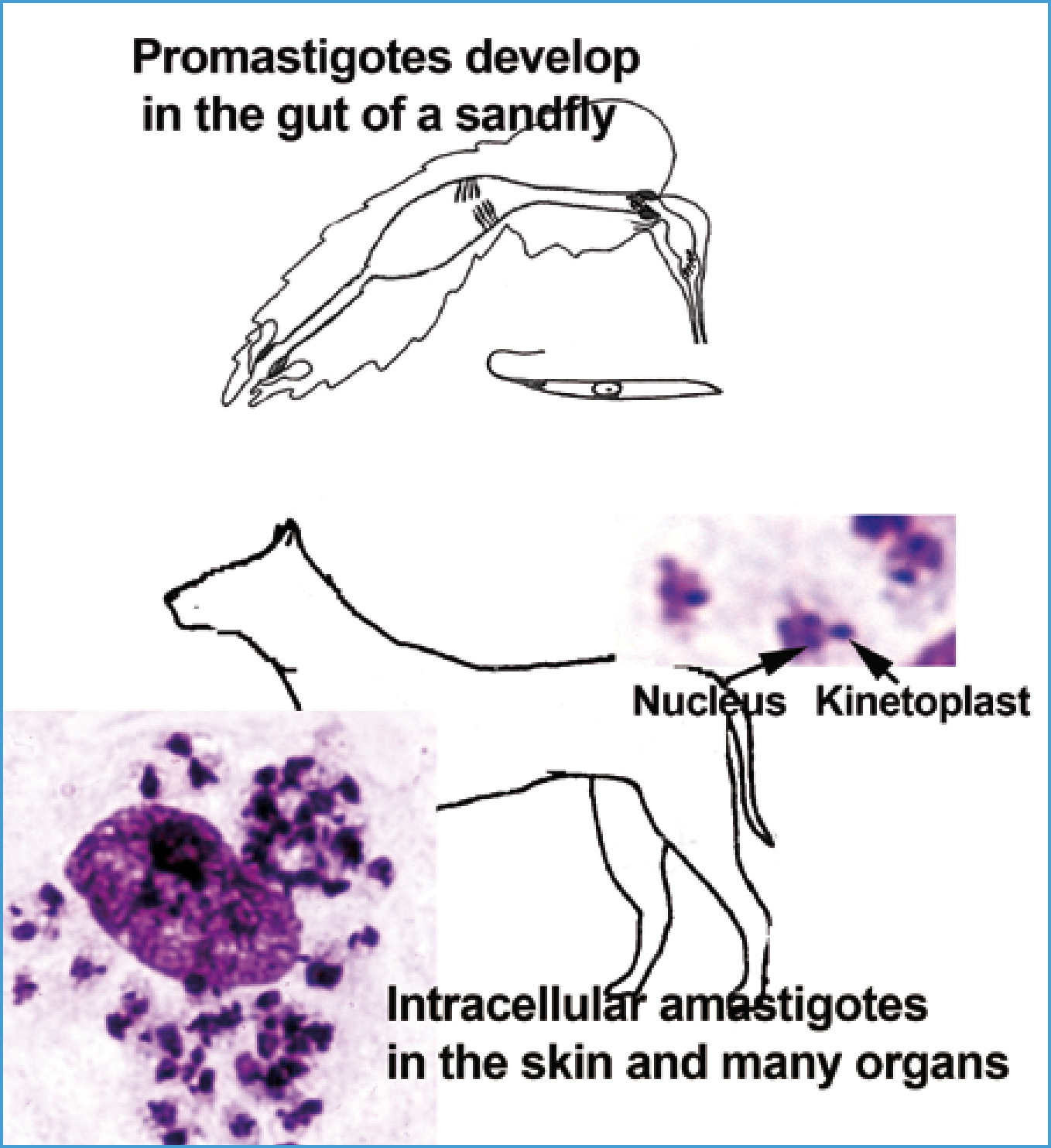

Phlebotomus female sandflies transmit Leishmania (Figure 1). Sandflies acquire Leishmania in infected cells ingested from the skin and blood of dogs. The Leishmania multiply asexually as promastigotes (elongate, unicellular forms with a single flagellum emerging anteriorly) in the midgut of the sandfly. These then move forward to the mouthparts for injection into the dog. Leishmania is an important human disease, yet details on sandfly biology are sparse. Eggs are laid and development occurs in organically rich, moist soils, i.e. Mediterranean shrub and forest (oak) at an altitude of 100–1200 m above sea level, in rodent or rabbit burrows in the leaf litter and soil, using animal faeces for development. Earthen floors of stables, chicken coops, rubbish in cellars might provide breeding areas, and certainly provide cool, humid sites where adult sandflies rest in the day, as

Females feed mainly outdoors after sunset during warm nights (over about 18°C), but some also feed indoors. The very small, 1.5 mm, delicate flies don't fly well unless it is windless. Conversely, they are blown on winds extending their habitat from the Mediterranean to Switzerland, southern Germany, and northern France where, potentially, local transmission might occur. Although sandflies occur in Britain, the species responsible for transmitting Leishmania are absent. Nonetheless, non-fly transmission has been documented in dogs (Owens et al, 2001; Gibson-Corley et al, 2008; Silva et al, Boggiatto et al, 2011). Vertical transmission to puppies, blood transfusion and sexual transmission are documented causes of infection, and parasites in skin ulcers, mucous membranes and saliva might be transmitted by bites from infected dogs. These alternate routes seem important in kennels of foxhounds in North America related probably to their husbandry. For example, some 9% of foxhounds housed in northern USA and Canada proved seropositive without evidence for sandfly transmission while some randomly selected pets and wild canids in the area and some other hunting breeds housed at the same kennels gave negative resuits (Gaskin et al, 2002; Gibson-Corley et al, 2008; Petersen and Barr, 2009). These routes may be the cause of rare autochthonous cases originating in dogs in northern Europe, including the UK, that have had no history of travel to an endemic area and in the absence of sandfly transmission (Harris 1994; Shaw et al 2008).

Leishmaniosis

Dogs are the main hosts of L. infantum. Once injected into the skin, the promastigote enters a cell, particularly a reticulo-endothelial cell, loses its flagellum and transforms to an amastigote. The smaller, rounded amastigote can be differentiated from other intracellular protozoa by the paired nucleus and smaller, darker staining kinetoplast (at the base of the now non-existent flagellum) (Figure 1). The amastigote multiplies asexually before destroying the cell and entering nearby cells in the skin or the circulation to other organs.

Risk of infection is high: 10–90% of dogs in endemic areas have been infected (Baneth et al, 2008; Solano-Gallego et al, 2009) — 1:10–1:50 show disease; others are incubating disease, while others are endemic nor Gradoni, 2002).

The response of individual dogs varies from ‘resistant’ to ‘susceptible’ with a probable genetic and immunological basis (Quinnell et al, 2003; Sanchez-Robert et al, 2008; Boggiatto et al, 2010; Reis et al, 2010). Dogs in Britain, a naive population (an unexposed population that potentially has not developed phenotypic or genetic resistance in response to the infection pressure of Leishmania), are more likely to be susceptible than dogs bred in endemic areas. Other factors that may favour clinical disease include high dose rate, concurrent disease, and immunosuppressive treatments. Dogs with Leishmania

Infections in cats are less common, have low parasite burdens with symptoms rare and occurring mainly in feline leukaemia virus positive cats (Martin-Sanchez et al, 2007; Sherry et al, 2011).

Diagnosis and treatment

Skin or lymph node biopsy or bone marrow aspirate can reveal amastigotes in Geimsa stained smears (Figure 1). PCR on lymph node or bone marrow is very sensitive; it can also be used on skin and blood cells, but with less senstivity. Serology (ELISA and in practice test kits — the titre is important) for antibodies is sensitive and specific. All these should be interpreted along with the clinical signs.

Therapy is costly and prolonged — clinical cure can take months, and, even if it is achieved, the dog remains infected with potential for relapse. The drugs, which are not licensed for use in dogs, have some toxicity. Clinical staging and treatments for dogs are given by Solano-Gallego et al (2011) and ESCCAP (http://www.esccap.org/). Treated dogs should be monitored for signs of relapse (antibody, hyperglobulinaemia) at 3 and 6 months and onwards; prolonged maintenance therapy might be required.

Mosquitoes

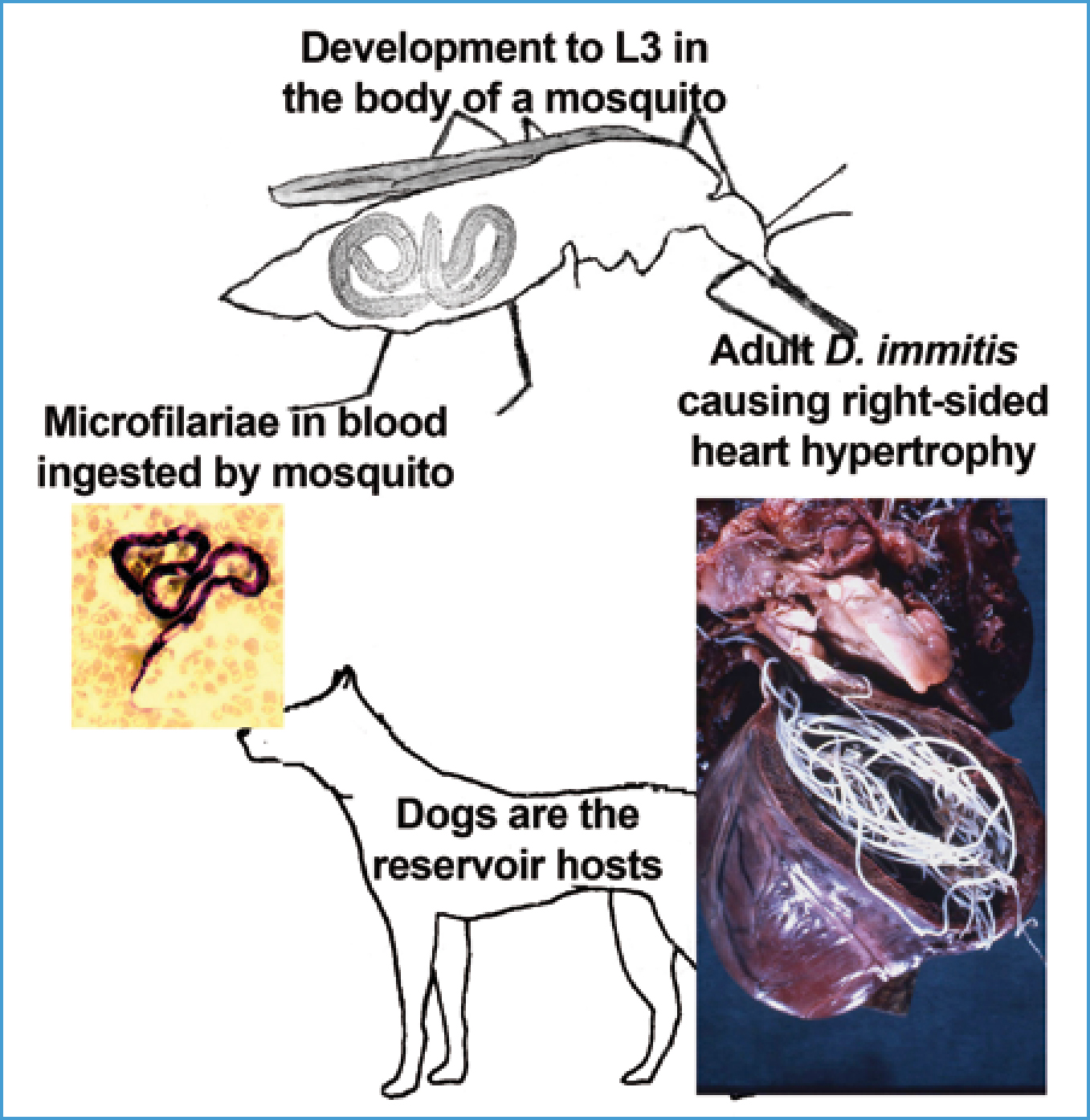

Dirofilaria immitis known as ‘heartworm’ and Dirofilaria-infected cats are kept indoors). Mosquitoes that could transmit Drofilaria repens in subcutaneous tissues are transmitted by a large number of Aedes, Culex and Anopheles mosquito species (Figure 3). Mosquito breeding occurs in a wide variety of waters (small containers, troughs, ponds, to marshlands). Adults are active particularly at night but some, i.e. Asian Tiger mosquitoes which are spreading in Europe, can feed in the day. Many species bite outdoors but some indoors (20% of Diirofilaria exist in Britain, but not at sufficient density, and summer time in the UK is not considered warm enough or long enough for development of the micofilaria (the first larval stage of D. immitis) to the third laval stage (L3) requires 29 days at a constant 18°C; mosquito survival is only about 30 days (Genchi et al, 2009). However, in a 15–year period to the mid-2000s, some meteorological stations in the UK (mainly southern England, but one in Scotland) recorded temperatures sufficient for development of Dirofilaria at least once and one station more frequently (Genchi et al, 2009). D. repens develops at similar temperatures, although it does occur in northern France and further east (Table 1).

|

Leishmania infantum

|

Dogs, cats, other species and a zoonosis |

Portugal, Spain, through southern France, Italy, the Adriatic Coast down to Greece and Turkey into Serbia and Bulgaria |

|

Dirofilaria immitis ‘heartworm’ |

Dogs, also cats and ferrets and a zoonosis |

Portugal, Spain, through southern France, Italy, southern Switzerland and Austria, the Czech Republic and Slovakia south and east to Greece, Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey |

|

Dirofilaria repens

|

Dogs and a zoonosis |

As D. immitis and northern France and Hungary |

| Thelazia callipaeda | Dogs and a zoonosis | In southern Italy and now in northern Italy, southeastern France, southern Germany, and southern Switzerland |

Dirofilariosis

Dirofilaria immitis

Immature worms spend 2 months in the tissues and reach the pulmonary arteries by 70–120 days; microfilariae are produced into the circulation from 6–9 months; and adults can live 5–7 years in dogs (Newton, 1968). Heartworms are initially found in the pulmonary arteries, causing pulmonary disease, with cardio-pulmonary disease developing later. Worms start in smaller arteries moving back towards the heart as they grow and more arrive. Worms are found in the right heart and rarely in the vena cavae in heavy infection when, in small dogs, worms relocate to the right heart, or after death in any dog.

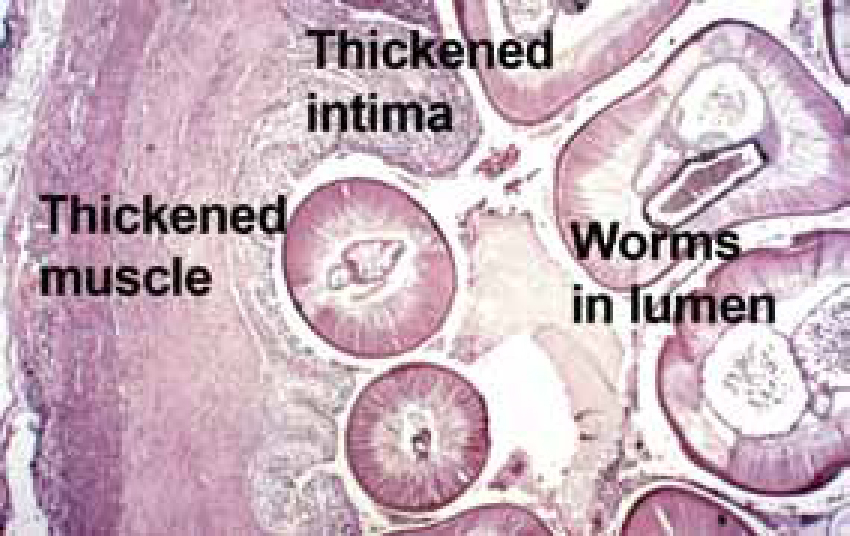

Dogs can carry light infections asymptomatically for years but, when worms die (naturally or as a result of treatment) and embolize to the lungs, signs might ensue. In heavier infections signs develop slowly as a cough becoming chronic, dyspnoea and weakness on exercise. D. immitis has within it symbiont Wolbachia bacteria that may induce some of the pathology but Wolbachia's importance requires further investigation. Physical worm and inflammatory damage cause thickening of the intima and muscle proliferation tries to maintain blood flow (Figure 4). This occurs first in small and medium arteries, spreading back, resulting in impedance to blood flow leading to pulmonary hypertension that later or in heavier infection leads to right-sided heart hypertrophy (Figure 3), congestive heart failure and congestive damage to liver and kidneys and ascites, which is usually fatal. The ‘caval syndrome’, which is usually fatal in 2–3 days, might occur in small dogs or where there is heavy infection, when worms back into the right heart and vena cavae producing right-sided heart failure, tricuspid murmur, severe liver congestion, intravascular haemolysis and haemoglobinurea.

Seroprevalence in cats is 5–20% that in dogs and many of these are infection negative (Genchi et al 2008). Most worms die on reaching the lungs so cats have few worms, commonly 1–4 worms, rarely 10. Many cats (30–50%) remain asymptomatic and self cure the infection in 1.5–4 years. Others show signs of infection when migrating worms arrive at the lungs and die, whether or not a few worms survive, with marked inflammation in the vessels and parenchyma and hypertrophy of arterial walls and occlusion, producing cough, dyspnoea, vomiting, known as heartworm-associated respiratory disease. Chronically infected cats might present acutely, even dying, when only one dead worm embolizes producing infarction and circulatory collapse (Lee and Atkins, 2010).

Ferrets are highly susceptible to D. immitis, just a few worms cause severe disease that may be fatal. Ferrets progress similarly to dogs but progress more rapidly (McCall et al, 2008).

Dirofilaria repens

Adults remain in subcutaneous and intermuscular tissues but produce microfilaria into the circulation. Infection might be observed as non-painful, fibrotic, subcutaneous nodules, particularly on the trunk. Rare allergic reactions to microfilaria occur.

Diagnosis and treatment

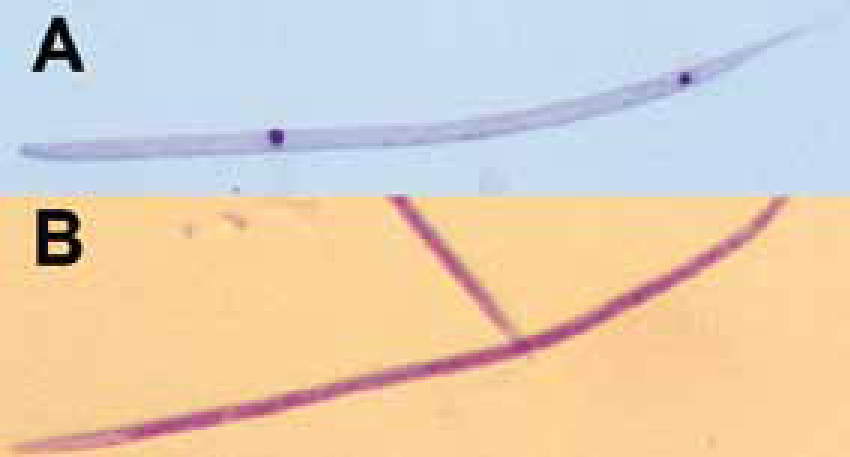

Microfilaria might be detected by movement in drops of blood/saline or in Geimsa stained smears. The Knot test (1 ml blood lysed in 9 ml 2% formalin, centrifuged, sediment examined) is more sensitive. Morphological differences between the different microfilaria species found in the blood of dogs are very difficult to discern, and differentiation is best made after staining with acid phosphatase (Figure 5). Some 30% of dogs are amicrofilaraemic, having sequestered microfilaria in the lungs in eosinophilic granulomata, or possibly prepatent (McCall et al, 2008). Cats commonly are amicrofilaraemic.

Detection of circulating antigen (ELISA or in practice test kits) is very sensitive and specific for D. immitis, often detecting one female worm. Dogs remain negative when prepatent, or in very light, or male only infections. Cats commonly are false negative having light or male only infections.

Radiography may show enlarged, tortuous, pulmonary arteries, truncating not tapering peripherally, and right ventricular enlargement. Angiography may detect worms as filling defects, and ultrasound may detect the worm's cuticle as two parallel lines, which is particularly useful in cats (Lee and Atkins, 2010).

Treatment of dogs requires a fairly toxic arsenical (and requires import). Inevitably worm embolism to the lungs occurs — in light infection consequences usually are unapparent; in heavier infections widespread embolism produces respiratory embarrassment. Cage rest and restricted exercise are essential for more than a month. Corticosteroids and heparin help.

Cats are not treated as severe thrombolembolism may induce acute disease; they should be monitored instead. Cats with signs of self embolism (acute onset dyspnoea and vomiting) should receive anti inflammatories. If treated for adults, fatal thromboemolism is likely in ferrets (McCall et al, 2008).

D. repens can be treated to remove the microfilaria, not adults, with monthly administration of a macrocyclic lactone (up to 2 years), also used to remove microfilaria of D. immitis after treatment for adults. Surgical removal of worms with long, flexible, alligator forceps is reported effective in caval syndrome and for cats (Jackson et al, 1966; Morini et al, 1998; Lee and Atkins, 2010).

Thelazia callipaeda

Thelazia callipaeda adults occur in the eyes of 60% of dogs in endemic areas (Table 1). Fly hosts, Phortica drosophilid males (Otranto et al, 2006), acquire the first larval stage (L1) of T. callipaeda and later deposit L3 when lapping eye secretions. The serrated cuticle of 1 cm long adults causes physical damage to the conjunctiva and mild to severe irritation, pain, conjunctivitis, lachrymation, and other signs (Malacrida et al, 2008). Worms are removed with forceps.

Control of flies and fly-borne parasites

Protection from pruritus

Pyrethroid fly repellents (NOT FOR CATS) (Table 2) markedly reduce, but not completely, biting by mosquitoes and sandflies preventing self excoriation. They probably also reduce attack by Phortica.

| Product name Insecticide (other drugs) | Species | Safe for pregnant/lactating bitches | For use only age/wt and above | Active against flies and duration | Also active against | Contraindications and warnings. Consult the data sheet and footnotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advantix spot on permethrin (imidacloprid) |

Dogs only |

Yes |

7 wks/1.5 kg |

Phlebotomus sandflies 2–3 weeks | Ticks and fleas |

Very toxic for cats - remove cats until site is dry and cats should not lick/groom the application area. Pets should not groom wet coat (induces salivation). Toxic orally. Rare skin sensitivity or behavioural changes (Gl, neurological) may be seen. Not to be used more than once weekly. |

| Aedes, Culex mosquitoes 3–4 weeks | ||||||

|

Stomoxys stable flies 4 wks |

||||||

| Scalibor Protectorband deltamethrin | Dogs only | Yes | 7 wks | Phlebotomus sandflies 5–6 months | Ticks | Not to be used on cats. Rare cases of dermatitis, or neurological signs (remove collar). Withstands wetting but remove collar before pet bathing or swimming for environmental effects. Not to be eaten. Children <2 years should not touch collar, children should not have prolonged contact sleeping with treated dog. Not to be used for the PETS treatment required 24–48 hrs before travel to Britain. |

| Culex mosquitoes 6 months | ||||||

| One wk to full efficacy |

Consult the data sheets. Macrocyclic lactones must be administered monthly for heartworm prophylaxis. Shampoos should not be used for a few days before and days to 2 wks after application of most products. Efficacy of most products will not be affected if the dog becomes wet, but prolonged wetting will reduce efficacy; in the latter case or in the case of heavy exposure, some products may be given more frequently. Care, veterinary advice and risk assessment is necessary when treating sick/debilitated animals. Do not use in cases of known hypersensitivity in human or animal to the active ingredients or alcohol. Do not handle pet until coat is dry, recently treated animals should not sleep with owners. Avoid inhaling and contact with mouth, eyes, skin. Gl, gastrointestinal.

Dirofilaria

D. immitis and D. repens are controlled by administration of a macrocyclic lactone (Table 2) monthly throughout the transmission season or the year and even to any pet that has travelled only briefly to an endemic area (McCall et al, 2008). These are highly effective killing worms up to 30 days of age in the tissues. Treatment starts 1 month after arrival in an endemic area and continues with 1–2 doses on return. Monthly administration must be stressed as efficacy is not as good against older worms if a dose is missed — there is some ‘reach back'/'safety net’ effect that may kill somewhat older worms but the animal still might be infected with a smaller number of smaller worms, these potentially causing less damage (McCall, 2005). An animal that has been abroad previously must be checked for adult heartworm and treated if necessary before prophylaxis is begun otherwise adverse effects might ensue.

Leishmania

Fly repellents significantly reduce, but do not prevent Leishmania transmission; incidence in treated versus untreated dogs was 51% to 84–92% lower over 2 years respectively (Quinnell and Courtney, 2009). Management must be recommended. Dogs should be kept indoors from before dusk until after dawn, the highest level of biting is outdoors just after dusk. Any sandflies biting indoors have poor flying capacity — cultural prevention in North Africa suggests they do not fly to higher floors; a fan will reduce attack (Kettle, 1995). Other measures include mosquito window or bed nets impregnated with pyrethroids. The best control is not to take the pet to countries where Leishmania is endemic.

Zoonotic implications

Note, while many humans are resistant to L. infantum, disease is possible and can be severe in children and the immunosuppressed. The travelling child also needs protection from flies. A Leishmania-infected dog has potential threat for transmission via parasites in skin ulcers and mucous membranes of the dog via dog bites or through sores to a child, as in North American foxhounds; some consider the pet should be euthanased, not treated. Dirofilaria infects humans, but only by mosquitoes, most commonly it is D. repens that causes nodules in subcutaneous, pulmonary and ocular tissues. T. callipaeda has been recorded in man (Otranto and Dutto, 2008).

Conclusions

Sandflies and mosquitoes occur in the UK. Species of sandflies here do not transmit Leishmania but the transmitting species is moving northwards. Species of mosquitoes in the UK are capable of transmitting Dirofilaria but temperatures and mosquito density seem limiting, although this may change. Potential for fly-borne parasite transmission increases as more and more infected pets travel from endemic areas. Further, with the changes in the PETS requirements it is likely that many more pets will travel to continental Europe without much veterinary intervention. Education for all owners attending a clinic becomes essential.