Fungal infections are an important cause of dermatoses in cats and dogs that can be investigated by veterinary nurses in general practice and treated under veterinary direction. When working up a skin case at first presentation, mycoses (conditions caused by fungi) should be on the differential list, however some mycoses are more common than others. This article aims to provide a brief overview of the presentation, aetiology, diagnosis, and treatment of various dermatomycoses.

Common conditions

Malassezia spp.

Malassezia is a genus of lipid-dependent yeasts that can be found as part of the normal flora on the skin of many animals. The most common species in dogs and cats is Malassezia pachydermatis, (Guillot and Bond, 2020) although there are several others, including Malassezia furfur and Malasse-zia sympodialis that can be seen in other animals as well as cats. Malassezia spp. dermatitis or otitis are the most common fungal skin infections seen in dogs (Bond et al, 2020); and studies have indicated that the peri-oral region and interdigital skin is frequently colonised (up to 80%) by M. pachydermatis in healthy dogs of various breeds (Guillot and Bond, 2020). Malassezia organisms were also found on cytology from the ears of over a third of cats in one study, and are known to be part of the normal ear flora (Tyler et al, 2019), although the prevalence of Malassezia spp. causing disease has not been fully investigated.

Aetiology

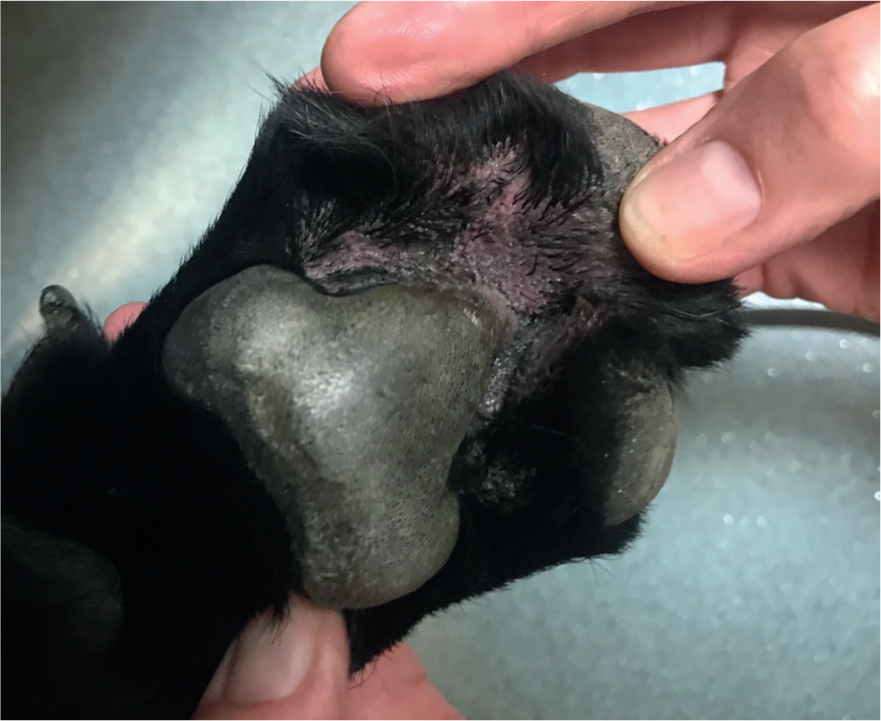

As Malassezia spp. are a normal part of the cutaneous microflora, they tend not to cause problems for healthy skin. However, when the skin becomes inflamed, such as in patients with allergic skin disease or in patients with numerous skin folds, numbers can increase and cause pruritus, known as Malassezia dermatitis (Figure 1) or otitis (Figure 2). It is important to note that Malassezia spp. are rarely pathogenic and as such rarely cause primary disease. If they are found in large numbers on samples, an underlying cause should be considered, investigated, and treated. Some breeds are predisposed to having higher numbers of Malassezia spp. on their skin and in their ears, such as Sphynx cats and Basset Hounds (Bond et al, 2020).

Diagnosis

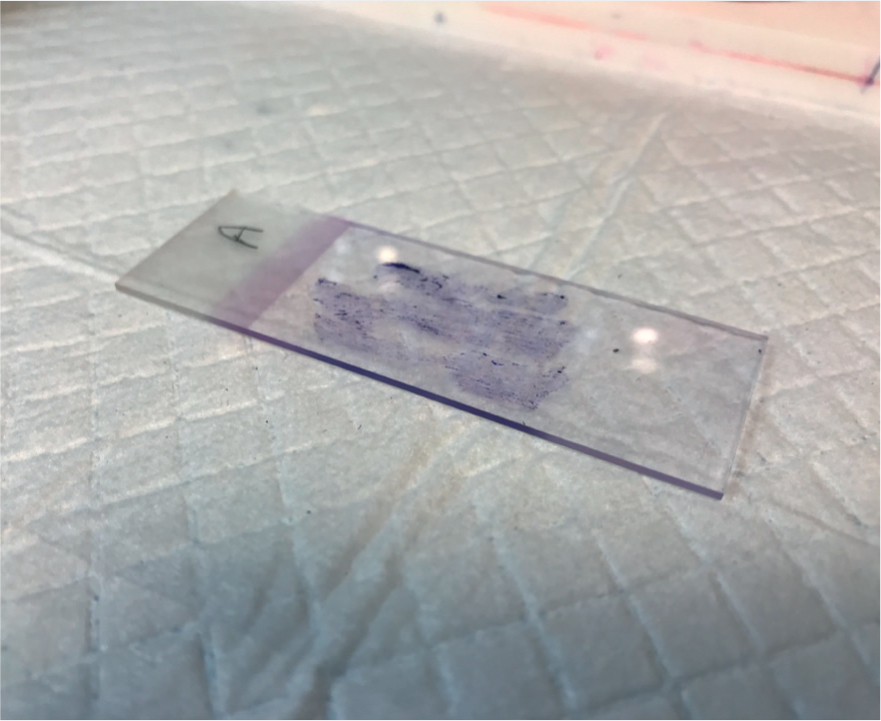

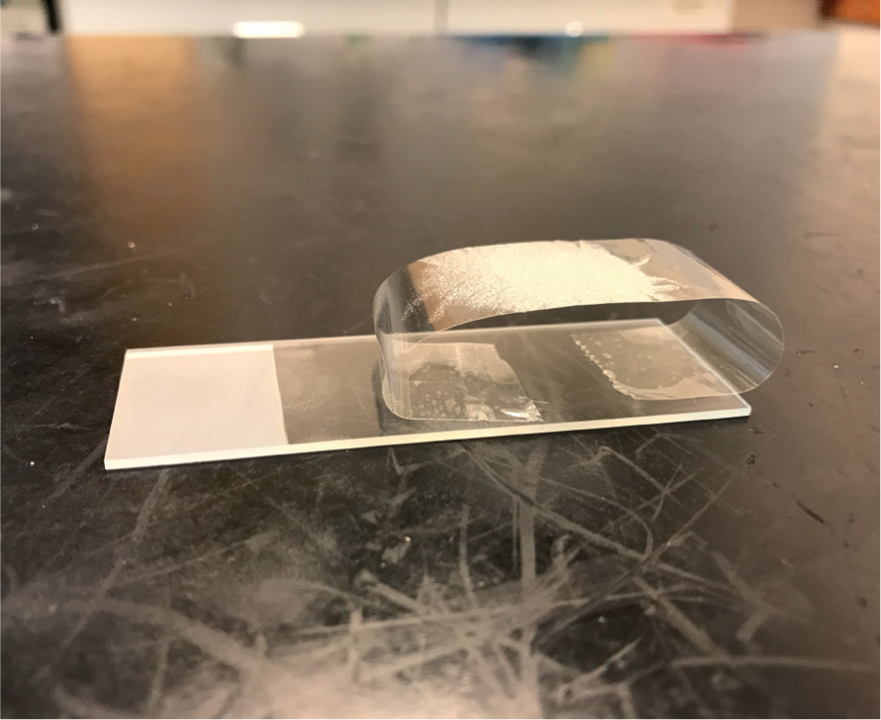

Diagnosis of Malassezia spp. from the skin can be easy in general practice if a microscope is available, and it does not require the use of external laboratory services. Depending on the anatomical area to be sampled, and the moistness of the lesion, there are different methods for acquiring a sample for microscopy. A direct impression smear (Figure 3) can be taken by pressing a microscope slide to a moist lesion or to an area that is quite flat. A tape strip (Figure 4) is useful for areas that are harder to access, such as inter-digitally. Sticky tape is pressed on the lesion three or four times to create a multi-layered sample. The tape is then attached to a microscope slide, as in Figure 4, to be stained. Once stained, one edge of the tape can be peeled off and the tape can be stuck down on the opposite side of the slide, acting like a cover slip. A cotton bud sample (Figure 5) can be taken from an ear or facial fold, for example. Gently rolling the sample on the slide transfers any cells, ready for staining. These samples should be stained using Diff-Quik® and examined using high-power oil immersion microscopy (Bond et al, 2020).

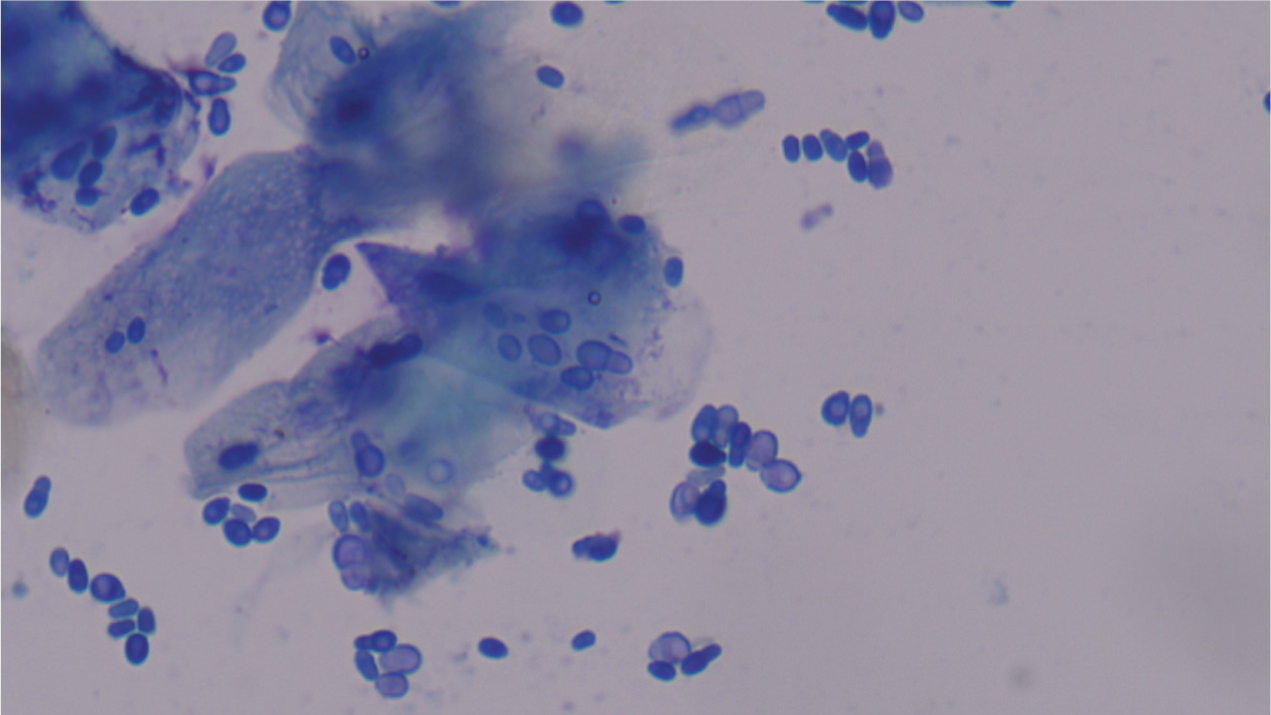

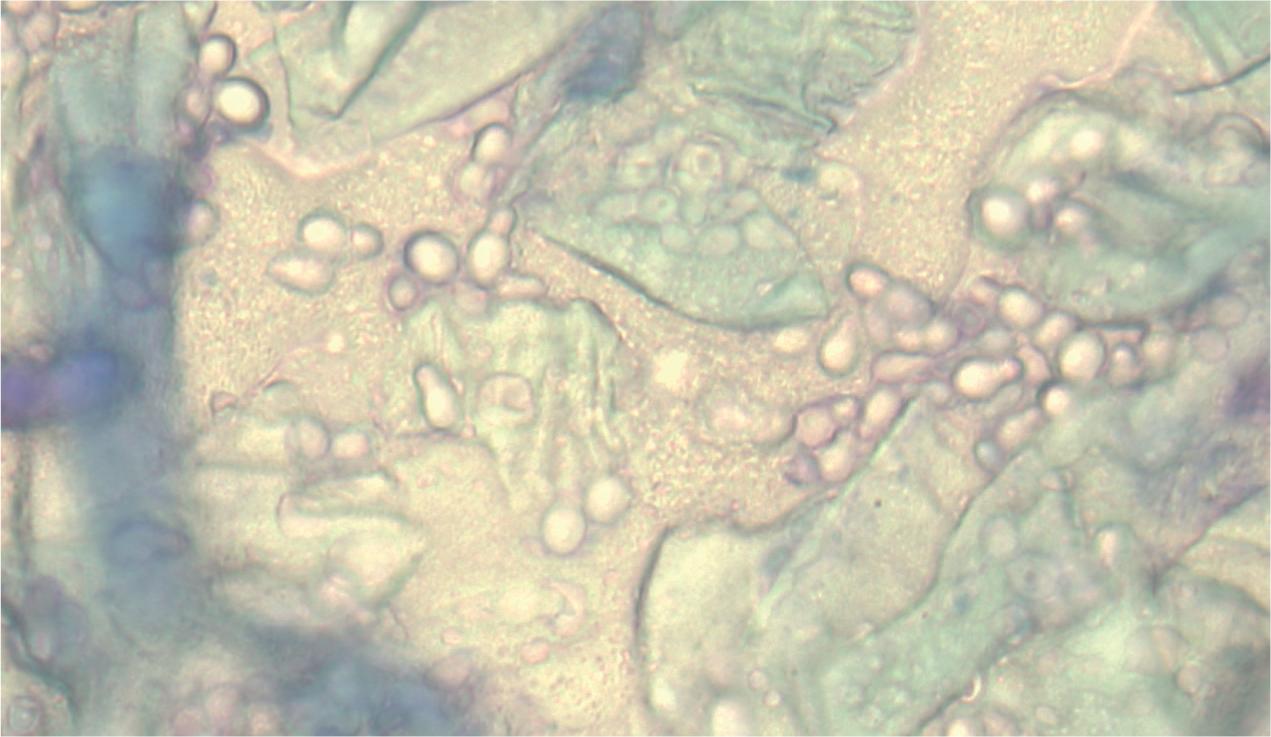

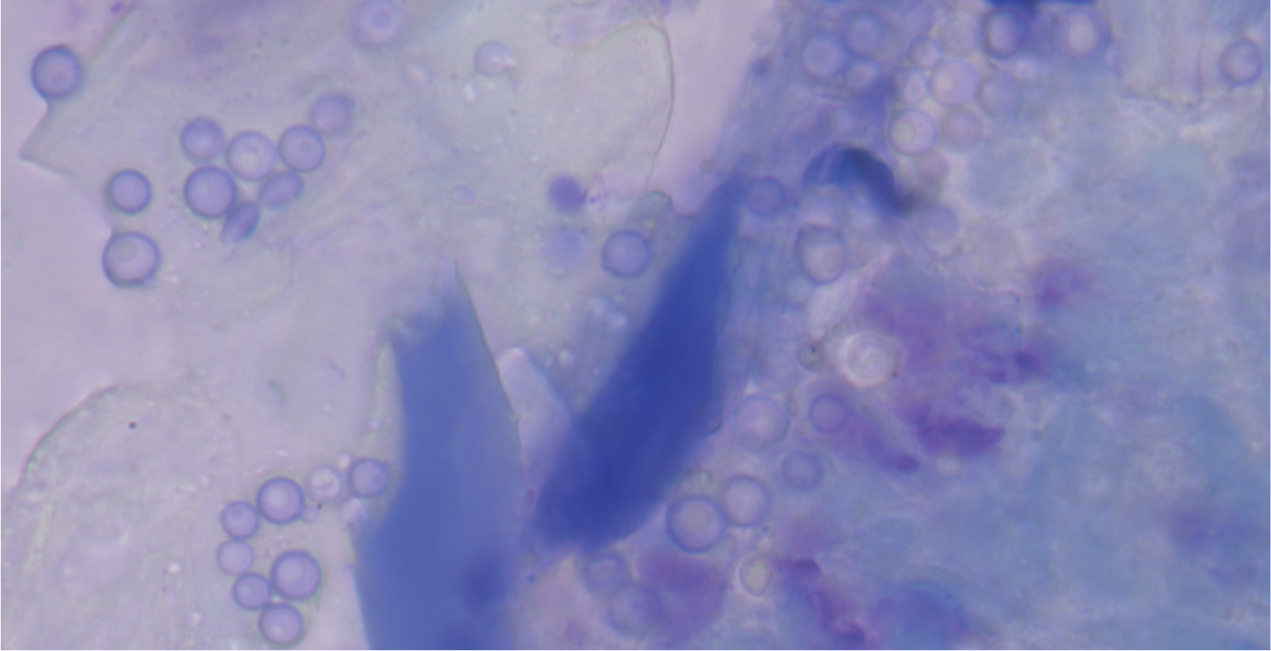

The appearance of Malassezia spp. can be described as ‘Russian dolls’ or ‘peanuts’ because of the classic shape they form when reproducing (Figure 6). Malassezia spp. may also be seen at different stages; where they are about to bud or have recently budded, they do not have the bilobed shape. Malassezia spp. tend to stain a deep blue or purple colour, however, if the sample is very greasy or waxy, this can prevent them from taking up the stain. They can still be visualised under the microscope, but they may have a ‘ghost-like’ appearance (Figure 7), and may be slightly harder to spot. While nurses are unable to make the diagnosis themselves, they are well-placed to help with diagnosis by examining slides, reporting findings and having these confirmed by the veterinary surgeon.

Treatment

Various medications and products are licensed for the treatment of Malassezia spp. dermatitis and otitis (Negre et al, 2008):

- Dermatitis — topical therapies, such as chlorhexidine shampoos, mousses or wipes, should be used as first line treatment. It is important that these contain over 3% chlorhexidine to have an effect on the Malassezia spp., therefore they should not be diluted. Some products contain additional antifungal medications (miconazole) and therefore the percentage of chlorhexidine can be slightly lower (2%) because of a potentiating effect. As a result of this, it is a POM-V product, and can only be prescribed by a veterinary surgeon. It is important to pay attention to the contact times for these products as some require 10 minutes contact before rinsing. An enilconazole dip is available; this is an off-license product as it is licensed for the treatment of dermatophytosis in dogs (and horses and cattle), however it can be useful for larger dogs with Malassezia spp. infection where bathing is difficult, as it does not require rinsing once applied. Again, this product is POM-V, but is one to consider. Oral ketoconazole (licensed) and itraconazole (offlicense tablets or licensed liquid for cats) can be used for refractory cases or patients that are unsuitable for bathing for any reason. Care should be taken as these medications can affect the liver; baseline biochemistry parameters should be checked before commencing treatment and every 6 months after. It is also important to know that these drugs can affect the elimination of other drugs, and can either prolong their action or cause overdose in some cases (Bond et al, 2020).

- Otitis — most proprietary licensed ear medications contain a steroid, an antibiotic, and an antifungal medication, such as miconazole, posaconazole and clotrimazole. Choosing an ear medication for Malassezia spp. otitis will often depend on whether or not there are also bacteria present, and which species of bacteria are present, as using a second line antibiotic, such as marbofloxacin, can lead to antimicrobial resistance later on. The strength of the steroid component is also a consideration when selecting a topical ear preparation.

Dermatophytosis

Dermatophytosis, colloquially known as ringworm, is an infectious, contagious, zoonotic superficial fungal skin disease. The most common dermatophytes in cats and dogs are Microsporum canis and Trichophyton mentagrophytes (Moriello, 2019).

Aetiology

The primary method of transmission of dermatophytes is direct contact with an infected animal, however fomite transmission can be seen. Because of this, dermatophytosis is more common when animals are kept in large numbers, for example in rescue centres or hoarding situations. Transmission requires not only contact with an infected individual or fomite, but also microtrauma of the skin to allow the spores to adhere and penetrate the epidermis. Without microtrauma, clinical disease may not occur although the animal may still be ‘culture-positive’ as an unaffected carrier. Dermatophytosis is usually a self-limiting disease; the host's immune system will eventually clear it. Treatment aims to speed the progression of the disease towards resolution and minimise the zoonotic risk. Hunting animals are at higher risk of dermatophytosis as a result of contact with wild animals, and Yorkshire Terriers and Persian cats have been found to be predisposed (Moriello et al, 2017).

Clinical appearance

Unlike in humans, where the typical appearance is a circular lesion, hence the name ‘ringworm’, dermatophytes in dogs mostly do not have a pathognomonic appearance. In cats, the typical appearance is circular areas of alopecia, with damage to the hairs, scaling and an erythematous margin. Lesions are typically located on the face; however they can appear anywhere (Frymus et al, 2013). Dermatophytosis has been known in both cats and dogs to cause alopecia, scaling, crusting, papular and pustular lesions, follicular plugging, erythema, hyperpigmentation, and dystrophic nail growth (Figure 8). Because of this variable presentation, dermatophytosis should appear on the list of differential diagnoses when working up dermatological cases (Moriello, 2019).

Zoonosis

Dermatophytosis is a zoonotic infection and, as such, if it is suspected it in any patients, it is important to ask owners if they have any lesions themselves, and find out if there are other pets in the household, and if they have lesions. When taking a clinical dermatological history, these questions can help you decide how high up dermatophytosis should be on your list of differential diagnoses. The rate of human infection from animals in unknown, but is assumed to be low unless the owners are immunocompromised.

Spores can reside in the environment for prolonged periods of time, even over a year (Moriello, 2017), so reinfection of pets and owners is possible; homes should be cleaned and disinfected and owners should be warned that this is a possible risk.

Diagnostic tests

There are various tests available for diagnosing dermatophytes, both in the veterinary practice and in external laboratories.

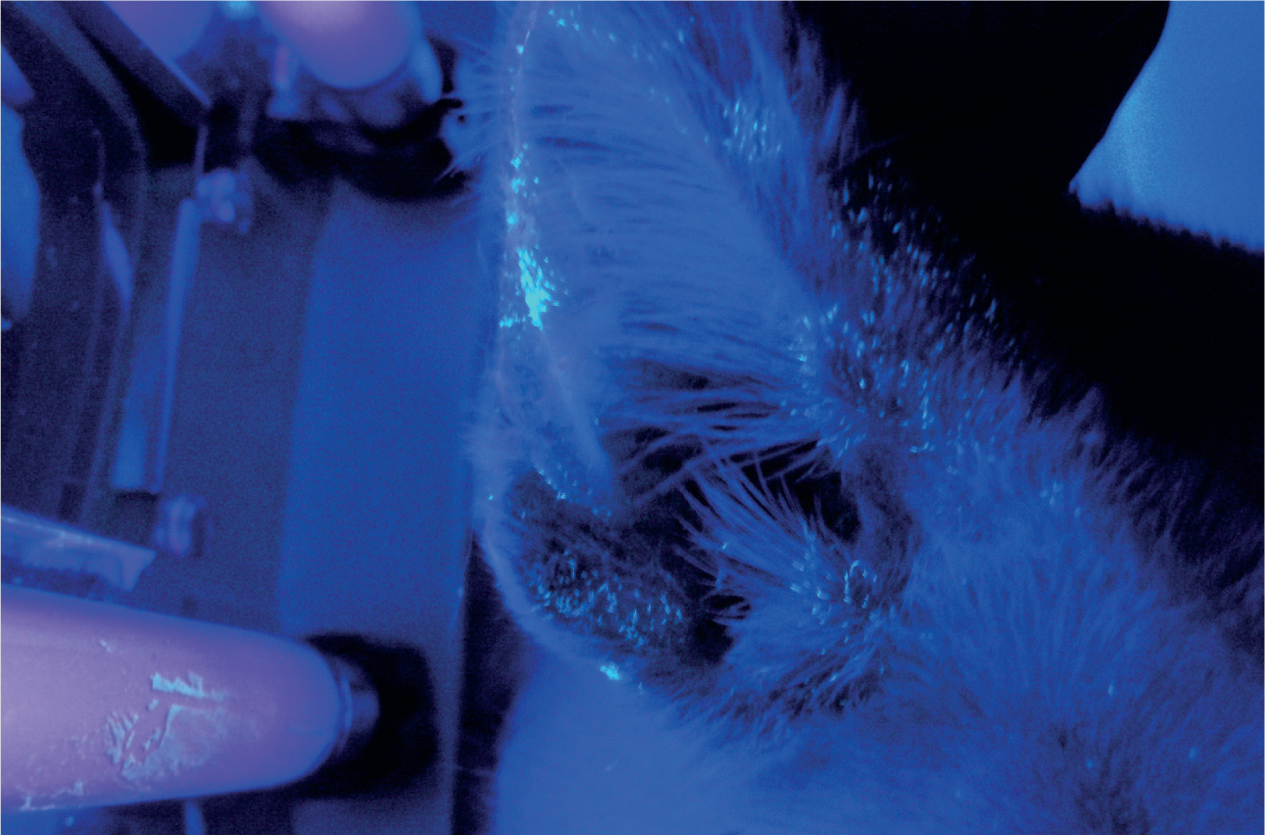

- Wood's lamp — it has previously been suggested that using a Wood's lamp for dermatophyte diagnosis is not very sensitive because only 40–50% of M. canis fluoresce; a recent study, however, found that up to 90% fluoresce (Moriello, 2017), meaning that Wood's lamp could be useful in dermatophyte diagnosis. M. canis are the only dermatophytes to fluoresce (other than the human dermatophyte Trichophyton schoenleinii), so a negative Wood's lamp test does not mean that the patient is dermatophyte negative. In a positive test the hairs fluoresce with an apple green colour, this should not be confused with the skin or any scale (dandruff) (see Figure 9) (Moriello et al, 2017).

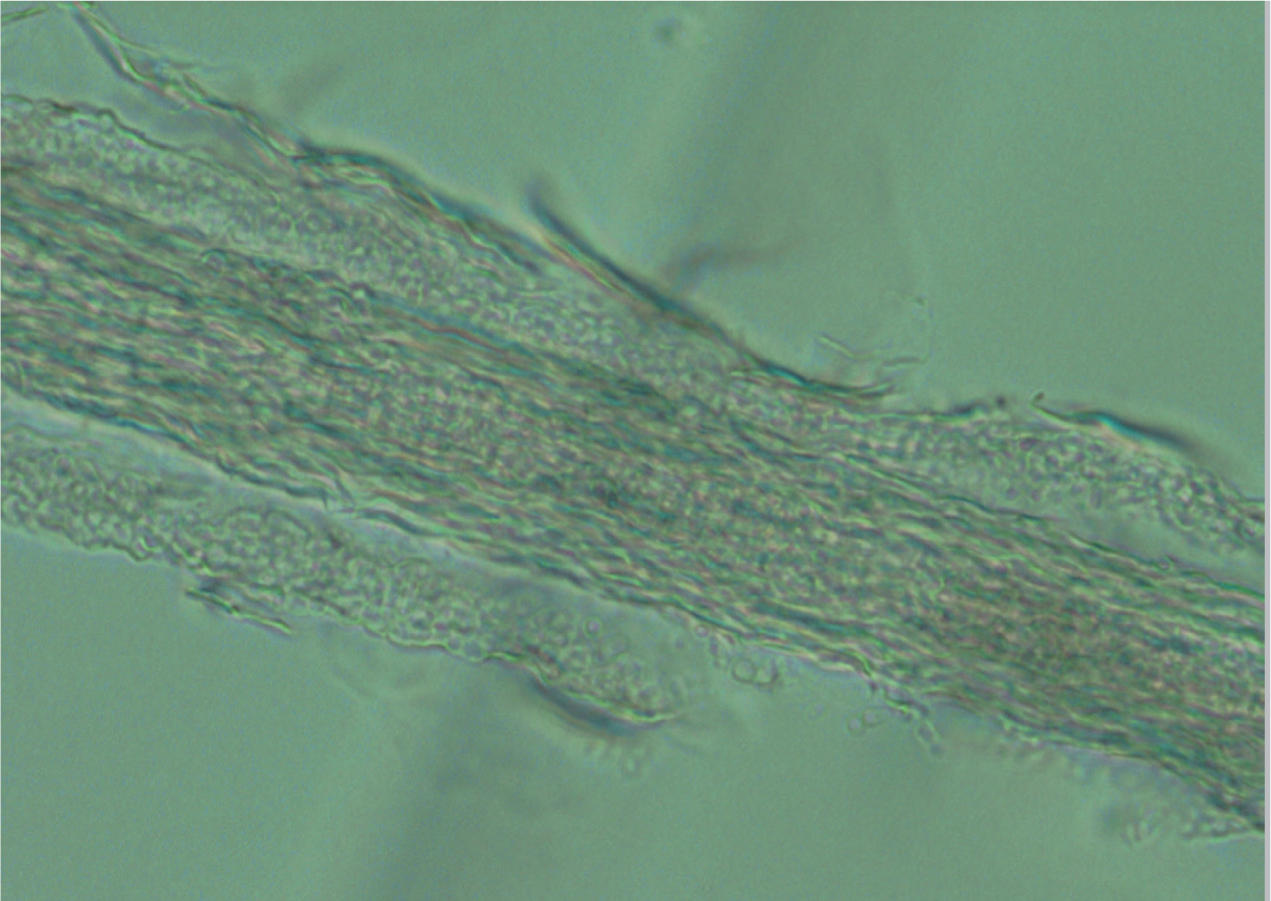

- Trichogram — hairs can be plucked and placed in liquid paraffin on a microscope slide, under a cover slip, for examination under low power using the microscope. Dermatophytes appear as a ‘bubble-wrap’ effect around the hairs; usually hair shafts are smooth, but a hair infected with dermatophytes will be uneven and covered in spores (Figure 10) (Moriello et al, 2017).

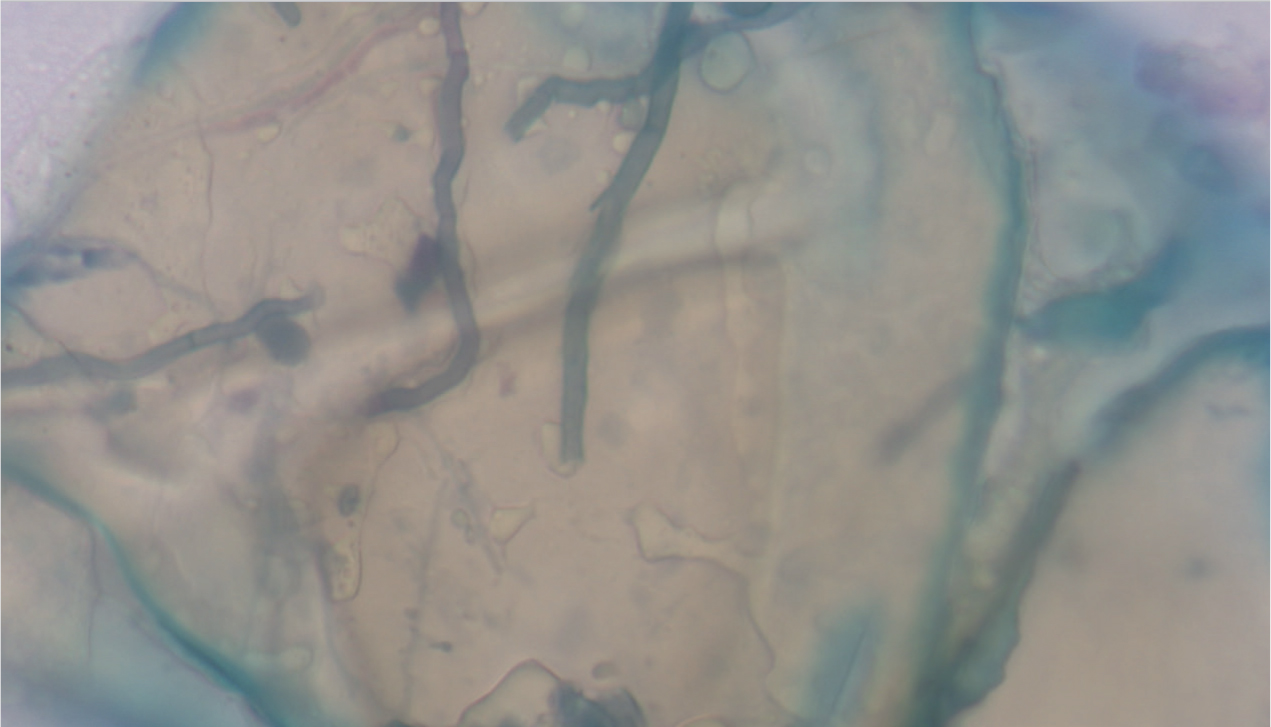

- Cytology — tape strip cytology of affected areas stained with Diff-Quik® may show spores or fungal hyphae (Figure 11). Other stains, such as lactophenol cotton blue, can be used if available. Seeing fungal elements only on cytology does not provide a definitive diagnosis, because some animals can be carriers of dermatophytes but not have an active infection (Moriello et al, 2017).

- In-house culture using dermatophyte test medium (DTM) — this can be performed by trained individuals to lower the risk of contamination, which can give false positive results. The chance of error is reduced when combined with cytological examination of the cultured colonies to confirm the positive result (Kaufmann et al, 2016).

- Laboratory culture — samples of hair and crust from lesions can be sent to an external laboratory for culture. Plucking the hairs and crust is an easy way to achieve this if the patient is amenable; they can be sent in a universal container. For more fractious patients, a sterile toothbrush can be rubbed over the affected areas and sent for culture. This is known as the Mackenzie technique.

Treatment

There are a number of products and medications licensed to help speed the progress towards clinical resolution (Moriello et al, 2017).

An enilconazole dip is licensed for the treatment of dermatophytosis in dogs, cattle and horses. The recommended method of use is to dilute 1 part in 50 parts water and apply every 3 to 4 days for four applications, as per the manufacturer's instructions. The affected areas must be thoroughly covered; some long-haired animals may require clipping beforehand. The solution can also be used on fomites such as bedding or brushes.

Chlorhexidine combined with miconazole, in a licensed shampoo formulation, has been used successfully in some cats with M. canis, in conjunction with oral antifungal medication (Moriello, 2017).

Ketoconazole is licensed for the treatment of M. canis and T. mentagrophytes in dogs and itraconazole liquid is licensed for M. canis in cats. Terbinafine is an off-license oral medication that has also shown good efficacy in treating dermatophytosis.

Successful treatment of dermatophytosis usually involves combined oral and topical medication, alongside environmental decontamination. Vacuuming and mechanical cleaning is important to remove infected material (hair), as well as disinfection, which can easily be undertaken in both veterinary and home environments, using appropriately diluted bleach (1:10). This should be performed daily until negative environmental cultures are obtained (where possible), or until the patients are no longer considered carriers, which can take many weeks. Infected patients should be isolated from un-infected patients (Carlotti et al, 2010).

Uncommon fungal infections

Other, more uncommon, fungal infections include candidiasis (Figure 12), cryptococcosis, sporotrichosis and alternariosis. Clinically, these mycoses can cause dermatitis similar to that of Malassezia spp. overgrowth, or cause purulent or crusting lesions, scaling, or nodular skin lesions. The nails can also be involved, causing dystrophic nail growth (Figure 13) (Dedola et al, 2009).

Cytology can be used to identify Candida spp. and Cryptococcus spp., as the yeasts are usually clearly visible. Hyphae and macroconidia of Sporothrix spp. and Alternaria spp. can also be found on cytology, however, differentiation between species can be quite hard using only cytology. Culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be used to speciate the fungi; PCR is a more sensitive test (Makri et al, 2020).

Treatment

Like dermatophytosis, oral and topical antifungal products are usually necessary for clinical resolution. Reducing any immunosuppressive medications may also be helpful, or treating any underlying conditions that are causing immunosuppression, as these may have predisposed the animal to infection (Dedola et al, 2009).

Conclusions

Fungal infections are an important differential diagnosis for canine and feline skin disease. They can be easy for veterinary nurses and veterinary surgeons to investigate and treat in general practice.

KEY POINTS

- Nurses are well places to be able to help the veterinary surgeon in diagnosing various fungal skin infections.

- Cytology is a simple way to identify various different fungi.

- There are various treatment methods available, including oral medication and topical products, such as dips and shampoos.

- Some infections, such as dermatophytosis, are zoonotic.

- There are some rarer infections that have been seen occasionally in the UK.