The ability to experience pain is universally shared by all mammals, including companion animals, and as members of the veterinary healthcare team it is our moral and ethical duty to mitigate this suffering to the best of our ability. This begins by evaluating for pain at every patient contact. However, and despite advances in the recognition and treatment of pain, there remains a gap between its occurrence and its successful management; the inability to accurately diagnose pain and limitations in, and/or comfort with, the analgesic modalities available remain root causes. Both would benefit from the development, broad dissemination, and adoption of pain assessment and management guidelines.

This article presents selected sections of the WSAVA Guidelines focusing on pain assessment. The full guidelines can be found on the WSAVA website (www.wsava.org). Additional web-based resources are also available as www.wsava.org including a webcast on pain assessment from the GPC Pre-Congress Day at the 2013 WSAVA World Congress.

Use of this document

This document is designed to provide the user with easy-to-implement, core fundamentals on the successful recognition and treatment of pain in the day-to-day small animal clinical practice setting. While not intended to be an exhaustive treatise on the subject matter, the text does provide an extensive reference list and there is additional material on the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) website (www.wsava.org) designed to provide resources for those wanting to further their knowledge of this subject matter based on the current literature.

There are no geographic limitations to the occurrence of pain, nor to the ability to diagnose it. The only limiting factors are awareness, education, and a commitment to include pain assessment in every physical examination. As such, the pain assessment guidelines herein should be easily implemented regardless of practice setting and/or location.

In contrast, there are real regional differences in the availability of the various classes of analgesics, specific analgesic products, and the regulatory environment that governs their use. This represents a significant hurdle to the ideal management of pain in various regions of the world, irrespective of the ability to diagnose. In the treatment section of these guidelines (not included here), these issues are taken into account by the provision of ‘tiered’ management guidelines beginning with comprehensive pain management modalities that represent the current ‘state of the art’ followed by alternative protocols that may be considered where regulatory restrictions on analgesic products prevent ideal case management. Owing to space limitations, tiered management cannot be listed for all situations, but the analgesics available can be selected from the recommended management. It should also be recognised that in some situations, whether due to a etiology or available analgesics, euthanasia may be the only moral or ethical (hence viable) treatment option available. Humane methods are presented.

Sections are given on the various product and procedure modalities including pharmacology, mechanism of action, indications, contraindications, dosing, and practical clinical notes to help guide the reader in tailoring the therapeutic protocol to the needs of the individual patient.

Recognise this document as providing guidelines only, with each situation unique and requiring the individual assessment and therapeutic recommendations that only a licensed veterinarian can provide. There are a number of statements that are the collective opinion of the authors, based on their cumulative experience with pain management gained within their respective fields but not yet evidenced via published data. It is the view of the group that providing this guidance is important in areas where to date there is little published work to underpin clinical pain treatment in dogs and cats.

The contents should also be put into context of the following pain assessment and management tenets:

We can't always know that our patient does hurt, but we can do our best to ensure that it doesn't hurt

Section 1: introduction to pain, its recognition and assessment

Understanding pain

Pain is a complex multi-dimensional experience involving sensory and affective (emotional) components. In other words, ‘pain is not just about how it feels, but how it makes you feel’, and it is those unpleasant feelings that cause the suffering we associate with pain. The official definition of pain by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) is: ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience, associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage’ (IASP, 2015). Pain is a uniquely individual experience in humans and animals, which makes it hard to appreciate how individuals feel. In non-verbal patients, including animals, we use behavioural signs and knowledge of likely causes of pain to guide its management. The conscious experience of pain defies precise anatomical, physiological and or pharmacological definition; furthermore, it is a subjective emotion that can be experienced even in the absence of obvious external noxious stimulation, and which can be modified by behavioural experiences including fear, memory and stress.

At its simplest, pain is classified as either acute or chronic. The distinction between acute and chronic pain is not clear, although traditionally an arbitrary interval of time from onset of pain has been used, e.g. pain of more than 3 months’ duration can be considered to be chronic.

Acute pain is generally associated with tissue damage or the threat of this and serves the vital purpose of rapidly altering the animal's behaviour in order to avoid or minimise damage, and to optimise the conditions in which healing can take place, stopping when healing is complete. Acute pain varies in its severity from mild-to-moderate to severe-to-excruciating. It is evoked by a specific disease or injury; it serves a biological purpose during healing and it is self limiting. Examples of acute pain include that associated with a cut/wound, elective surgical procedures, or acute onset disease, e.g. acute pancreatitis. In contrast, chronic pain persists beyond the expected course of an acute disease process, has no biological purpose and no clear end point and in people, as well as having an effect on physical wellbeing, it can have a significant impact on the psychology of the sufferer.

Chronic pain is generally described in human medicine as pain that persists beyond the normal time of healing, or as persistent pain caused by conditions where healing has not occurred or which remit and then recur. Thus acute and chronic pain are different clinical entities, and chronic pain may be considered as a disease state.

The therapeutic approaches to pain management should reflect these different profiles. The therapy of acute pain is aimed at treating the underlying cause and interrupting the nociceptive signals at a range of levels throughout the nervous system, while treatment approaches to chronic pain must rely on a multidisciplinary approach and holistic management of the patient's quality of life.

Many dogs and cats suffer from long-term chronic disease and illness which are accompanied by chronic pain. During the lifetime of the animal acute exacerbations of the pain may occur (breakthrough pain), or new sources of acute pain may occur independently which may impact on the management of the underlying chronic pain state (‘acute on chronic pain’). For these animals aggressive pain management is required to restore the animal's comfort.

Physiology and pathophysiology of pain

This section has been removed and is available on the WSAVA website.

Recognition and assessment of acute pain in cats

Acute pain is the result of a traumatic, surgical, medical or infectious event that begins abruptly and should be relatively brief. This pain can usually be alleviated by the correct choice of analgesic drugs, most commonly opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). For successful relief of pain, one must first look for it and recognise it. It is recommended that assessment of pain is incorporated into Temperature, Pulse and Respiration (TPR) examinations, making pain the 4th vital sign we monitor. Cats that have been injured or undergone surgery should be monitored closely and pain must be treated promptly to prevent it from escalating. Treatment must be continued until the acute inflammatory response abates. The degree of trauma dictates the intensity and duration of the inflammatory response but treatment may be required for several days. Feral cats require preemptive administration of analgesics based on the severity of the proposed surgical procedure rather than based on their behaviour; in addition, interactive pain assessment is not possible in this population (Robertson, 2005).

Neuroendocrine assays measuring β-endorphin, catecholamines and cortisol concentrations in plasma have been correlated with acute pain in cats; however, these are also influenced by other factors such as anxiety, stress, fear and drugs (Cambridge et al, 2000). Objective measurements such as heart rate, pupil size and respiratory rate have not been consistently correlated with signs of pain in cats — therefore we depend on subjective evaluation based on behaviour (Brondani et al, 2011). A multidimensional composite pain scale (UNESP-Botucatu) for assessing postoperative pain in cats has been validated and can be applied in the clinical setting as a useful tool (Brondani et al, 2013).

Pain assessment and recognition

Take into consideration the type, anatomical location and duration of surgery, the environment, individual variation, age, and health status. The cat should be observed from a distance then, if possible, the caregiver should interact with the cat and palpate the painful area to fully assess the cat's pain. A good knowledge of the cat's normal behaviour is very helpful as changes in behaviour (absence of normal behaviours such as grooming and climbing into the litter box) and presence of new behaviours (a previously friendly cat becoming aggressive, hiding or trying to escape) may provide helpful clues. Some cats may not display clear overt behaviour indicative of pain, especially in the presence of human beings, other animals or in stressful situations. Cats should not be awakened to check their pain status; rest and sleep are good signs of comfort but one should ensure the cat is resting or sleeping in a normal posture (relaxed, curled up). In some cases cats will remain very still because they are afraid or it is too painful to move, and some cats feign sleep when stressed (Taylor and Robertson, 2004).

Facial expressions and postures: these can be altered in cats experiencing pain: furrowed brow, orbital squeezing (squinted eyes) and a hanging head (head down) can be indicators of pain. Following abdominal surgery a hunched position and/or a tense abdomen is indicative of pain. Abnormal gait or shifting of weight and sitting or lying in abnormal positions may reflect discomfort and protection of an injured area. Comfortable cats should display normal facial expressions, postures and movement after successful analgesic therapy. Figure 1 provides examples of normal postures and facial expressions and those that may be indicative of pain.

Behavioural changes associated with acute pain in cats: reduced activity, loss of appetite, quietness, hiding, hissing and growling (vocalisation), excessive licking of a specific area of the body (usually involving surgical wounds), guarding behaviour, cessation of grooming, tail flicking and aggression may be observed. Cats in severe pain are usually depressed, immobile and silent. They will appear tense and distant from their environment (Lamont, 2002).

Dysphoria versus pain: thrashing, restlessness and continuous activity can be signs of severe pain in cats. However, these can also be related to dysphoria. Dysphoria is usually restricted to the early postoperative period (20–30 minutes) and/or associated with poor anaesthetic recoveries after inhalant anaesthesia and/or ketamine administration and/or after high doses of opioids. Hyperthermia associated with the administration of hydromorphone and some other opioids may lead to anxiety and signs of agitation in cats.

Recognition and assessment of acute pain in dogs

Acute pain occurs commonly in dogs as a result of a trauma, surgery, medical problems, infections or inflammatory disease. The severity of pain can range from very mild to very severe. The duration of pain can be expected to be from a few hours to several days. It is generally well managed by the use of analgesic drugs. The effective management of pain relies on the ability of the veterinarian, animal health technician and veterinary nurse to recognise pain, and assess and measure it in a reliable manner. When the dog is discharged home, owners should be given guidance on signs of pain and how to treat it.

Objective measurements including heart rate, arterial blood pressure and plasma cortisol and catecholamine levels have been associated with acute pain in dogs (Hansen et al, 1997); however, they are unreliable as stress, fear and anaesthetic drugs affect them. Thus, evaluation of pain in dogs is primarily subjective and based on behavioural signs.

Pain recognition

Behavioural expression of pain is species specific and is influenced by age, breed, individual temperament and the presence of additional stressors such as anxiety or fear. Debilitating disease can dramatically reduce the range of behavioural indicators of pain that the animal would normally show, e.g. dogs may not vocalise and may be reluctant to move to prevent worsening pain. Therefore, when assessing a dog for pain a range of factors should be considered, including the type, anatomical location and duration of surgery, the medical problem, or extent of injury. It is helpful to know the dog's normal behaviour; however, this is not always practical and strangers, other dogs, and many analgesic and other drugs (e.g. sedatives) may inhibit the dog's normal behavioural repertoire.

Behavioural signs of pain in dogs include:

Pain assessment protocol

The most important step in managing acute pain well is to actively assess the dog for signs of pain on a regular basis, and use the outcomes of these assessments (through observation and interaction) along with knowledge of the disease/surgical status and history of the animal to make a judgement on the pain state of the dog. It is recommended that carers adopt a specific protocol and approach every dog in a consistent manner to assess them for pain. Dysphoria should be considered where panting, nausea, vomiting or vocalisation occurs immediately following opioid administration.

Where a dog is judged to be in pain, treatment should be given immediately to provide relief. Dogs should be assessed continuously to ensure that treatment has been effective, and thereafter on a 2–4 hourly basis.

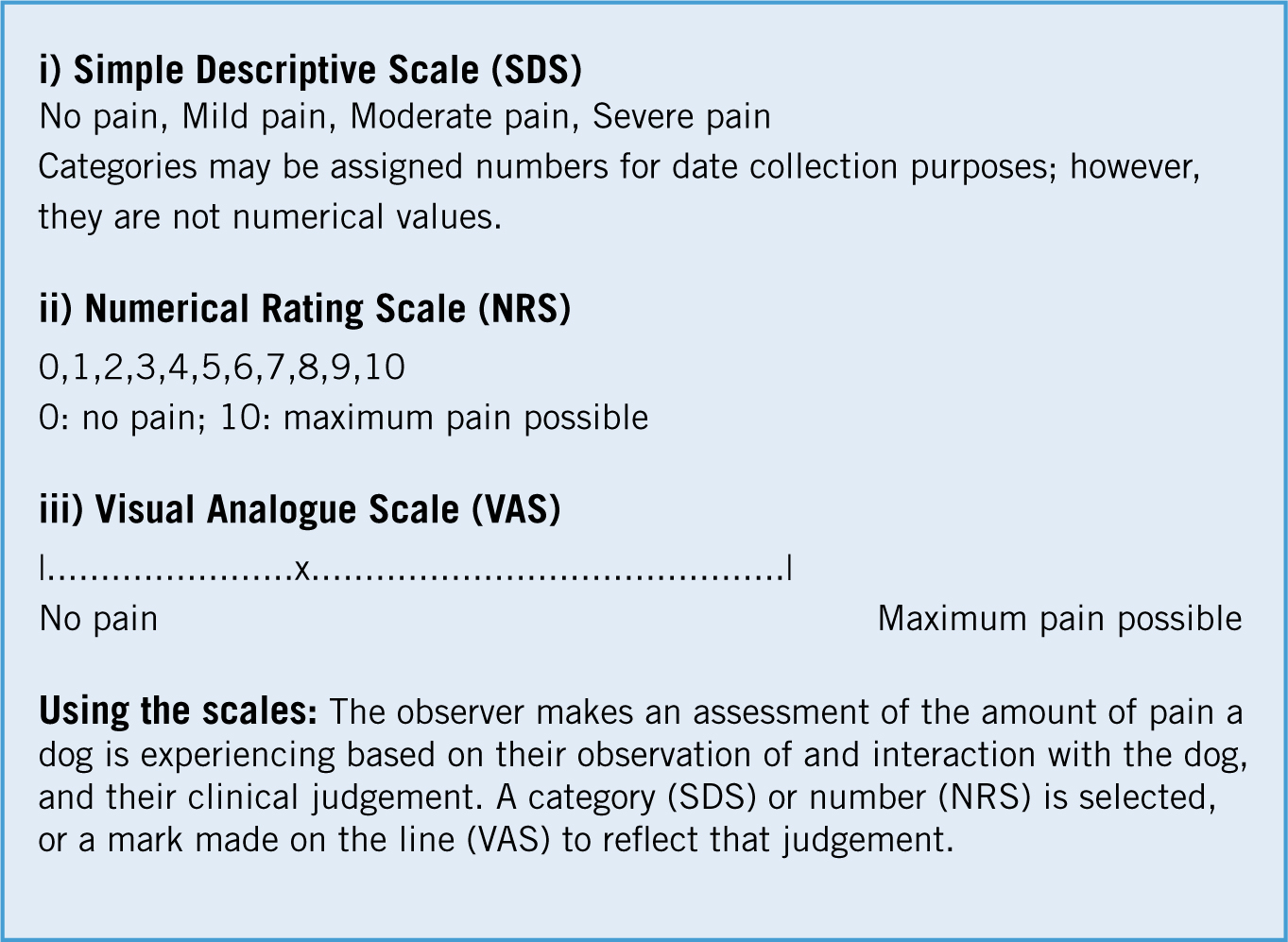

Pain measurement tools: these should possess the key properties of validity, reliability and sensitivity to change. Pain is an abstract construct so there is no gold standard for measurement and as the goal is to measure the affective component of pain (i.e. how it makes the dog feel), this is a real challenge. This is further compounded by the use of an observer to rate the dog's pain. Few of the scales available for use in dogs have been fully validated. Simple unidimensional scales, including the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and the Simple Descriptive Scale (SDS) (Figure 5), have been used (Holton et al, 1998; Hudson et al, 2004). These scales require the user to record a subjective score for pain intensity. When using these scales, the observer's judgment can be affected by factors such as age, gender, personal health and clinical experience, thus introducing a degree of inter-observer variability and limiting the reliability of the scale. However, when used consistently, these are effective as part of a protocol to evaluate pain as described above. Of the three types of scales described (and there are others in this category), the NRS (0 to 10) is recommended for use due to its enhanced sensitivity over the SDS and increased reliability over the VAS.

Composite scales include the Glasgow Composite Measure Pain Scale and its short form (CMPS-SF) (Holton et al, 2001; Reid et al, 2007), and the French Association for Animal Anaesthesia and Analgesia pain scoring system, the 4A-Vet (Reid et al, 2007). The CMPS-SF, validated for use in measuring acute pain, is a clinical decision-making tool when used in conjunction with clinical judgement. Intervention level scores have been described (i.e. the score at which analgesia should be administered), thus it can be used to indicate the need for analgesic treatment. The instrument is available to download online (University of Glasgow, 2015). The 4A-Vet, which is also available online (4aVet, 2015), is available for use in cats and dogs, although evidence for its validity and reliability have not yet been demonstrated. The Colorado State University (CSU) acute pain scale for the dog (Colorado State University, 2015) combines aspects of the numerical rating scale along with composite behavioural observation, and it has been shown to increase awareness of behavioural changes associated with pain. The University of Melbourne Pain Scale combines physiologic data and behavioural responses (Firth and Haldane, 1999). Japanese Society of Study for Animal Pain (JSSAP) Canine Acute Pain Scale (written in Japanese) is a numerical rating scale combined with behavioural observation and can be downloaded from the website (ACRF, 2015). All of the composite scales above are easy to use and include interactive components and behavioural categories.

Recognition and assessmnet of chronic pain in cats

Chronic pain is of long duration, and is commonly associated with chronic diseases, e.g. degenerative joint disease (DJD), stomatitis and intervertebral disk disease. It may also be present in the absence of ongoing clinical disease, persisting beyond the expected course of an acute disease process — such as neuropathic pain following onychectomy, limb or tail amputation. As cats live longer there has been an increased recognition of chronic pain associated with certain conditions, which has a negative impact on quality of life (QoL). In recent years, treatment options for some cancers in companion animals have become a viable alternative to euthanasia, and managing chronic pain and the impact of aggressive treatment protocols has become a challenging and important welfare issue.

Pain recognition is the keystone of effective pain measurement and management. The behavioural changes associated with chronic pain may develop gradually and may be subtle, making them most easily detected by someone very familiar with the animal (usually the owner).

Owner assessments are the mainstay of the assessment of chronic pain, but how these tools should be constructed optimally for cats is not fully understood. Many of the tools for measuring chronic pain in humans measure its impact on the patient's QoL, which includes physical and psychological aspects. Very little work has been performed in cats, but there are some studies assessing QoL or health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in cats being treated with antiviral agents (Hartmann and Kuffer, 1998), and cats with cardiac disease (Reynolds et al, 2010; Freeman et al, 2012), cancer (Tzannes et al, 2008) and diabetes mellitus (Niessen et al, 2010). There is a growing understanding of behaviours that may be associated with the chronic pain of musculoskeletal disease in cats (Clarke and Bennett, 2006; Bennett and Morton, 2009). Recently, progress has been made in developing an owner-directed instrument for the assessment of chronic musculoskeletal pain in cats (Zamprogno et al, 2010; Benito et al, 2013a; Benito et al, 2013b), and also in understanding what owners consider to be important for their cat's QoL (Benito-de-la-Vibora et al, 2012). At the present time, there are no validated instruments available. However, we recommend that behaviours are assessed in these broad categories:

Each of these should be assessed and ‘scored’ in some manner (e.g. using either a descriptive, numerical rating or visual analogue scale). Re-evaluation over time will help determine the impact of pain, and the extent of pain relief.

Recognition and assessment of chronic pain in dogs

Chronic pain is of long duration and is commonly associated with chronic diseases. It may also be present in the absence of ongoing clinical disease, persisting beyond the expected course of an acute disease process. As dogs live longer there has been an increase in the incidence of painful chronic conditions such as osteoarthritis (OA) and in recent years the treatment of cancer in companion animals has become a viable alternative to euthanasia. For many chronic conditions, chronic pain is a challenge as is the impact of aggressive treatment protocols. Treatment options for chronic pain are complex, and response to treatment is subject to much individual variation. Accordingly the veterinarian must monitor health status effectively on an ongoing basis in order to tailor treatment to the individual.

Chronic pain recognition

Pain recognition is the keystone of effective pain management. The behavioural changes associated with chronic pain may develop gradually and may be subtle, so that they can only be detected by someone very familiar with the animal (usually the owner). In people, chronic pain has both a physical and a psychological impact which adversely affect the patient's QoL. As a consequence many of the tools for measuring human chronic pain measure its impact on the patient's QoL. At present, a few tools have been described to evaluate chronic pain in dogs and these have provided information about the range of alterations in the demeanour, mood and behaviour of dogs as a consequence of chronic pain. Broadly these can be categorised as follows:

Chronic pain measurement

Owner assessments are the mainstay of the assessment of chronic pain in dogs. Functional assessment, QoL and HRQoL tools have been developed and used (Wojciechowska and Hewson, 2005; Arpinelli and Bamfi, 2006). QoL measures used in veterinary medicine vary from simple scales tied to certain descriptors of behaviours (Ahkstrom et al, 2010) to broad, unconstrained assessments (Lascelles et al, 2007; Brown et al, 2008; Lascelles et al, 2010). Questionnaires have been developed to assess HRQoL in dogs with DJD, cardiac disease (Freeman et al, 2005), cancer (Yazbek and Fantoni, 2005; Lynch et al, 2011), chronic pain (Wiseman-Orr et al, 2004; Wiseman-Orr et al, 2006), spinal cord injuries (Budke et al, 2008; Levine et al, 2008) and atopic dermatitis (Favrot et al, 2010), while some are less specific (Wojciechowska et al, 2005a and b).

Several instruments focused mainly on functional assessment (Clinical Metrology Instruments, CMIs) have been developed for canine OA and have undergone a variable degree of validation (Innes and Barr, 1998; Hielm-Bjorkman et al, 2003; Hudson et al, 2004; Brown et al, 2007; Brown et al, 2008; Hercock et al, 2009; Hielm-Bjorkman et al, 2009). Such questionnaires typically include a semi-objective rating of disease parameters such as ‘lameness’ and ‘pain’ on either a discontinuous ordinal scale or a visual analogue scale.

At the present time, the most fully validated instruments available are:

GUVQuest is an owner-based questionnaire developed using psychometric principles for assessing the impact of chronic pain on the HRQoL of dogs, and is validated in dogs with chronic joint disease and cancer. The Canine Brief Pain Inventory (CBPI) has been used to evaluate improvements in pain scores in dogs with OA and in dogs with osteosarcoma. The Helsinki Chronic Pain Index (HCPI) is also an owner-based questionnaire and has been used for assessing chronic pain in dogs with OA and, along with the CBPI, has been evaluated for content validity, reliability (Brown et al, 2007; Hielm-Bjorkman et al, 2003) and responsiveness (Brown et al, 2008; Hielm-Bjorkman et al, 2009). The CMI from Texas A&M (Hudson et al, 2004) has been investigated for validity and reliability but not responsiveness. The Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs (‘LOAD’) CMI has been validated in dogs with chronic elbow OA, and has been shown to be reliable with satisfactory responsiveness (Hercock et al, 2009). Recently, its validity for both forelimb and hindlimb OA was demonstratred (Walton et al, 2013). The JSSAP Canine Chronic Pain Index is an owner-based questionnaire written in Japanese and has been used for assessing chronic pain in dogs with OA.

Out of this work some key messages have emerged:

Recognising chronic pain — osteoarthritis as an example

Evaluating the canine OA patient consists of a combination of a veterinary assessment or examination, and the owner's assessment. The overall assessment of the negative impact of OA on the patient involves an evaluation of four broad categories:

These are all interconnected. Careful assessment of these four categories and their adverse effects will guide the prioritisation of treatment strategies. To fully assess these four categories, the clinician needs to gather data on:

Such a complete assessment will involve input from both the veterinarian (physical and orthopaedic examination) and the owner (owner completed QoL, HRQoL and Functional Assessments) and forms a baseline for future assessment.

Assessing response to treatment of pain in cats and dogs

Assessing the response to pain treatment/intervention strategies is a fundamental aspect of effective pain management. Too often dogs and cats are given one-off doses of analgesic drugs without effective follow-up. Methods of assessing pain in dogs and cats, both acute and chronic, are described in other sections.

Key principles of assessing response to treatment:

Acute pain

Dogs and cats should be assessed on a regular basis following surgery, in the early recovery period every 15–30 minutes (depending on the surgical procedure) and on an hourly basis thereafter for the first 6–8 hours after surgery. Thereafter, if pain is well controlled, 3–6 hourly assessment is recommended. The exact time interval depends on the severity of the surgery, the type of drugs used to manage pain and other factors relating to the animal's physical status. If in doubt about pain status re-assess the animal in 15 minutes.

Chronic pain

Dogs and cats should be assessed on a regular basis guided by the evidence below:

There is an evidence base for the key domains of behaviour that alter in association with chronic pain (see sections Recognition and assessment of chronic pain in cats and Recognition and assessment of chronic pain in dogs). This should be the basis of exploration with owners at initial presentation and on subsequent re-evaluation of progress.