House soiling problems (defined simply as the deposition of urine and/or faeces in unacceptable places from a human perspective) are one of the most common reasons for owners to sense a breakdown in their relationship with their pet and seek professional advice. The behaviour is distressing from a human perspective, but is also a sign that all is not well for the cat. There are a number of potential causes of house soiling behaviour and the most important part of investigating these cases is to establish the underlying motivation. The four important differential diagnoses are:

In a breakdown of cases seen at Vicky Halls' Referral Practice in 2014 (n=195) the distribution of cases shows the importance of all cats presenting with house soiling problems being given a thorough veterinary examination before being investigated purely from a behavioural perspective (Box 1). Most cases have one or more presenting problems, for example urine spraying together with elimination related to primary social and environmental factors, or intercat aggression with urine spraying. For the purpose of these statistics the behaviour noted reflects the veterinary surgeon's initial referral.

When looking at figures taken from 2008 (Box 2) and comparing to 2014 one of the noticeable differences is the number of cases with an underlying medical aetiology being referred for a behavioural consultation. The reduction from 9% of the case load to 1% is encouraging and hopefully reflects an increase in veterinary awareness of the fact that these cases require an adequate health work up before being labelled as a behavioural problem. The fact that the level of FIC cases has remained more static reflects the fact that these cases are medical in aetiology but require a significant amount of behavioural input as part of their management. It can often be beneficial to involve a suitably qualified behaviourist to deal with this aspect of the treatment plan (Cameron et al, 2004; Westropp and Buffington, 2004; Buffington et al, 2006).

It is the authors' opinion that these numbers vastly underestimate the incidence of house soiling in the wider population, as it remains, anecdotally, a common reason for relinquishment to rehoming facilities. In addition, many cases may not be brought to the attention of veterinary practices because a large percentage of the cat owning public in the UK do not regularly visit a veterinary practice.

Role of the veterinary team

There are three areas in which the veterinary team has a role in dealing with house soiling issues in cats.

This article will cover the issue of identification of existing problems and a part two will address the prevention and treatment of house soiling problems.

Identification of existing house soiling problems

Cases of house soiling do not always present without proactive questioning on the part of the veterinary team. Many owners still believe that this is not a veterinary matter as it is not perceived as ‘medical’ and some owners are embarrassed about the problem and reluctant to raise the subject. Including a routine behavioural questionnaire in all booster appointments is one way of increasing detection of cases. Asking direct questions to the client about their enjoyment of their relationship with their pet may also help to uncover house soiling issues.

Once the veterinary team are aware that there is an issue of house soiling the initial approach involves a combination of medical investigation and history taking. Ruling out any potential underlying medical aetiologies, including FIC, is a priority.

Medical investigation

It is important to review the medical history to get an overview of the cat's physical wellbeing and establish a chronology of events, including when the problem was first brought to the attention of the veterinary surgeon. Physical examination is the first step in ruling out potential medical causes for house soiling but this is likely to be combined with further tests such as urinalysis and, if conditions such as FIC are suspected, imaging may also be needed (Buffington et al, 1997).

History taking

A systematic approach to history taking is essential in these cases as significant information leading to identification of specific stressors will not necessarily be forthcoming. Information about behaviours and events can sometimes seem innocuous and unworthy of note to the owner, yet deeply revealing to the veterinary team or behaviourist. Asking questions which will reveal this detail is an important part of the history taking process and the issues which may require specific investigation include:

If veterinary nurses are going to try to tackle house soiling cases within the practice it is important to set aside enough time to obtain a comprehensive history. Taking a systematic approach to this process will help nurses to gather the most relevant information in as time effective a way as possible. The categories of information that need to be gathered include the following:

Within each of these categories there will be numerous questions that need to be asked. The first step is to better understand the physical and social environment of the home and suggested approaches are outlined in Boxes 3–6.

The aim of the questions relating to the environment is to detect any ways in which natural feline behaviour may be compromised (for example if the environment does not provide for natural feline coping strategies of hiding and elevation or if other cats in the neighbourhood have been able to enter into the cat's core territory).

Once the information has been gathered about the physical and social environment that the cat(s) are living in it is important to expand the questioning to gather details about the day to day management of the cats including how their resources are delivered. Some of the questions that can be helpful to ask in regards to husbandry and management are given in Box 7.

The aim of these questions is to establish whether the provision of resources, and in particular litter facilities, could be compromising normal feline toileting behaviour or whether other sources of stress can be identified which could be triggering a marking behavioural response. Information about feeding arrangements are particularly important. In feline terms feeding is a solitary behaviour and the provision of food as a social facilitator in large gatherings is a human concept. Communal delivery or indeed preparation of food is therefore potentially stressful for the cat. In addition to information about food and latrines it is also important to ask about locations of water sources and resting places and gather information about how the cat uses the territory that is available to it.

Aids to history taking

House maps

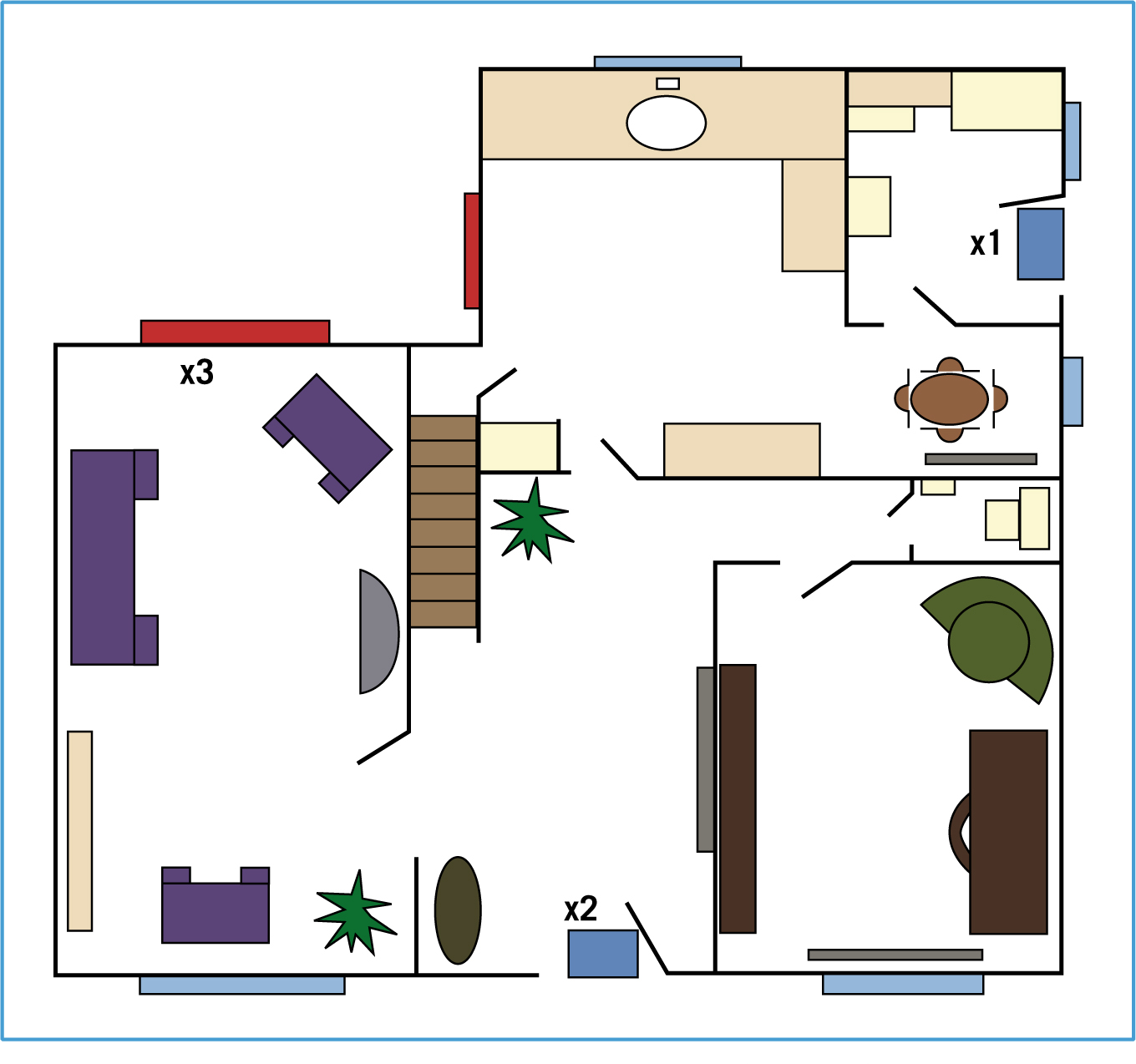

Ideally cat behaviour assessments will take place in the home, as the environment influences the development of house soiling, but this is rarely feasible in a general practice context. When this is the case the use of video footage and even the conducting of consultations via Skype or FaceTime can allow for the collection of important information about the physical environment. In addition a ‘house map’ may be used to good effect to provide a two-dimensional plan of each floor of the home on which the owner can mark information about resource distribution as well as the sites of deposits (Box 8 and Figure 1).

Assessing social grouping

Multi-cat households do not necessarily represent one cohesive social group. A social group is defined as: two or more cats, either related or familiar to each other, that share a territory and exhibit behaviours that promote social cohesion, such as allogrooming, allorubbing, and playing or resting together (Bradshaw et al, 2012; Carney et al, 2014).

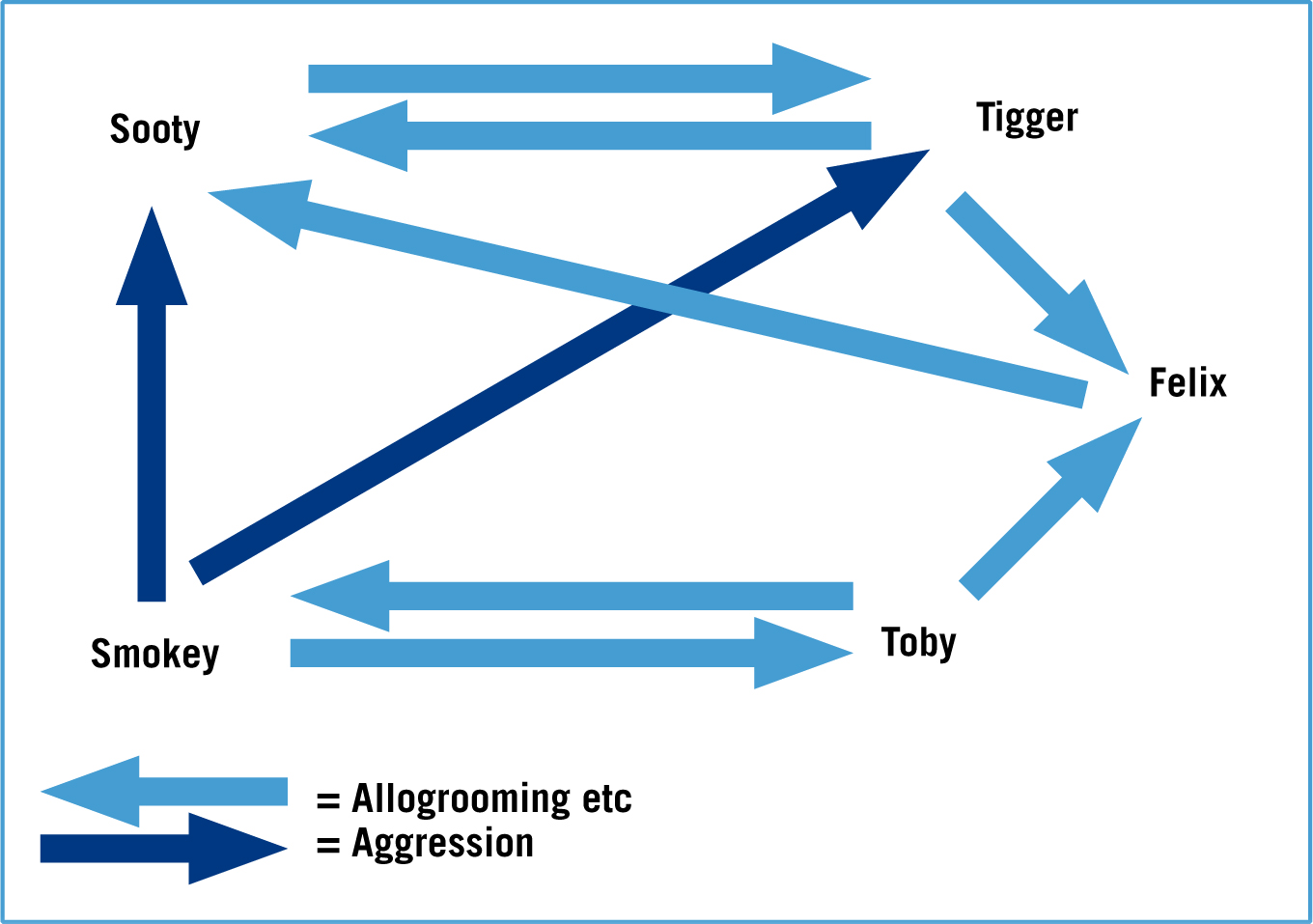

It is an important part of the history taking process to identify how each cat relates to, or perceives, the other. This can be achieved by writing the names of the cats on a piece of paper and asking the owner to indicate which cat exhibits affiliative behaviour (such as allogrooming, allorubbing, chirruping, tailup greeting, resting and playing together) and which cats exhibit agonistic behaviour (such as aggressive vocalisation, staring and active aggression). The owner should also indicate the direction in which the behaviour flows between two cats, for example, one cat may groom another but the behaviour is not reciprocated (Figure 2). Information about social groups will be crucial when putting together a treatment plan as resource distribution needs to be tailored to the number of social groups within a household rather than the number of cats.

Carrying out a stress audit

The purpose of exploring and gaining such extensive history is to conduct, as comprehensively as possible, a complete ‘stress audit’ for the individual cat.

When discussing the potential stressors in the home environment it is worth emphasising that challenging situations for cats come in forms that look innocuous and irrelevant when viewed from a human perspective. Owners will often be shocked when confronted with the fact that an issue may be stress-related. Any discussions with owners relating to this subject should therefore focus on the cat's perspective and how, as a species, there are many differences that set them apart from humans and even other companion animals.

The fact that the cat is a territorial, self-reliant predator will influence its perception of the world around it and determine what is considered to be a stressor. The lack of biological need for sociability is also relevant and owners need to appreciate that their cat is capable of enjoying group living, but only under specific circumstances, particularly regarding the abundance of food and other resources. As a self-reliant species the motivation to remain free from danger is paramount and cats thrive in circumstances that are familiar and routine. For this reason novel objects or smells in a cat's territory are explored with caution and any situation within a home environment that represents a significant change to the norm, for example building an extension or laying new carpet, could break routine and be sufficiently unfamiliar to cause distress.

It must be remembered that what is stressful for one cat will be of little consequence to another and may even be regarded as a positive experience. The temperament of the cat, in combination with the stressors that can be identified within the specific home environment, will therefore dictate whether or not they have a negative impact. For example a potentially anxiety-provoking stimulus would be likely to have a greater impact on a cat that is inherently nervous. The potential role of pain in these cases cannot be underestimated either as it has a significant impact on a cat's experience of its social and physical environment, particularly in cases of chronic pain (see Figure 3). If the stressors are significant the next challenge is to assess how the cat's distress will be manifested emotionally and physically.

It is likely that numerous stressors will be present in the home environment. These stressors have a cumulative impact so the presence of an obvious stressor and subsequent stress response should not preclude continuing investigation of other aspects of the cat's life via a thorough ‘stress audit’ (Mills et al, 2014). It is also important to remember that stressors can be predominantly sensory, for example strong or threatening odours (such as cigarette smoke and smells of other cats) or sounds (party-wall neighbours or traffic noise).

Making a diagnosis

The information gathered from the history taking will be evaluated in the light of the results from any medical investigation and it is important to remember that an interplay between emotional stress and physical disease has been well established (Westropp et al, 2006). In cases of FIC the role of stressors, such as moving house and living in multi-cat households, has been identified (Cameron et al, 2004; Westropp et al, 2006) and even when a medical diagnosis is made the role of behavioural and environmental modification in the management of the condition will still need to be considered.

When medical aetiologies and FIC have been ruled out, it is necessary to establish whether or not the house soiling represents marking or elimination. The stress audit outlined above is helpful in this process and will be crucial when deciding on treatment options for the individual case. However there is a final phase of history taking that is important in making the differentiation between underlying motivations. This phase concerns the house soiling itself and will involve asking questions about the onset of the problem, if the owners can recall this, the pattern of the deposits and the behaviour of both the cat(s) and the owner. Some suggested questions for this section of the history taking process are included in Box 9.

Who is responsible?

In some cases there may be more than one cat responsible in a multi-cat environment and identification of the actual perpetrator is obviously crucial. Sometimes owners will see the cat depositing the urine or faeces but often this is not the case and more investigation may be needed. The use of webcams and CCTV may be an option for some owners, but not everyone has this technology available to them. Fluorescein has been suggested as a potential aid to the diagnostic process and is given orally (Neilson, 2003). The urine from the treated cat will glow under a Wood's lamp and this can help to determine which cat is responsible for the deposits. There are some limitations to this approach, since the pH of the urine can affect the fluorescence, but it can be a helpful starting point in a difficult multi-cat household.

Marking

Urine spraying is a normal marking behaviour, representing a visual and olfactory form of feline communication. In the neutered population it appears to be particularly relevant to the sprayer as a comforting gesture in areas of conflict. The aim of the mark is to reassure the individual and to reduce the likelihood of confrontation. Typical characteristics of urine marking include a standing posture with an upright, quivering tail, raised hindquarters (some cats tread with their hind feet) and passing a stream of urine. This can vary in volume but is typically less than 2 mls, appearing as a small trickle. The frequency of urine marking varies, but usually does not correspond with the cat's normal micturition pattern. Some cats, particularly females, may squat and mark on horizontal surfaces but the majority of deposits will be found in significant locations on vertical surfaces, where they are most likely to be found by other cats.

Urine spraying is either a sexual or reactional behaviour (Dehasse, 1997). Males and females that have not been neutered mark with urine to advertise their sexual receptivity to others. Neutering intact cats dramatically reduces the incidence of urine spraying (Hart and Barrett, 1973).

Reactional spraying occurs in response to a change in the cat's environment, either social or physical, particularly in its core area, where it eats, sleeps and plays. Confident and anxious cats alike will spray.

Problematic reactional urine marking occurs when cats perceive threat within the indoor environment and use marking to reduce confrontation and increase personal sensation of safety. It is the perception of threat that is the underlying problem and the marking behaviour is simply a sign of that exaggerated or unjustified emotional reaction.

In cases of indoor marking behaviour cats will frequently mark the same area, common sites include:

Using the floor plans provided by the owner helps to identify the primary sites for the deposits and this can assist in determining the underlying motivation. If they occurred originally around the cat flap, external doors or windows then it would indicate that the stressor is external, for example a new cat in the territory. If it occurred on internal doors, stairs or hallways then it would suggest that the stressor is internal, for example another cat in the household. Treatment will be related to identification of stressors, removal of them or limitation of their effect and in the long term altering the cat's emotional reaction to them.

Elimination related to primary environmental or social factors

Unacceptable indoor elimination is likely to present very differently from marking behaviour in terms of the locations targeted and the frequency and volume of the deposits (Heath, 2007). When elimination behaviour is occurring in unacceptable locations it is important to consider normal toileting in cats and identify why this particular cat is finding its preferred location or substrate more attractive than the litter facilities provided by the owner. When cats eliminate urine and faeces they look for quiet and secluded locations where they will not be disturbed. The substrate is usually conducive to creating an indentation in which to eliminate and raking to cover it after the elimination has occurred. In house soiling cases related to elimination, rather than marking, the location of the deposits and the location of the litter tray should be compared in terms of their ability to offer privacy and seclusion. The litter material should also be considered as a potential hinderance to use of the tray and features of the tray itself, such as its size and whether it is hooded or not will also need to be taken into account.

Conclusions

Investigation of house soiling cases is time consuming and challenging but by taking a logical approach to history taking and observing the environment of the cat, either directly through house visits or indirectly via videos and house plans it is possible to differentiate between the underlying motivations. Deposition of urine and faeces in unacceptable locations in the house is distressing for owners and indicative of compromised welfare for the cat. Once a diagnosis of motivation has been made a treatment approach can be formulated and this will be covered in part two of this article.