The veterinary environment can be stressful for patients and owners alike. The waiting room is the first exposure patients get to the veterinary environment, and can dictate their response to the environment thereafter. This article explores why it is important for both owners and staff to be able to recognise this stress response (SR) and why reducing anxiety within the waiting room is beneficial for all concerned. The article identifies methods that can be used and measures that can be taken to reduce a patient's SR within the waiting room, and therefore their emotional anxiety levels.

Recognising stress

In the first instance, it is important to be able to recognise when a patient is experiencing a SR. There are certain behavioural signs that communicate that the patient is experiencing this SR. This article focuses on canine and feline signals, as these are predominantly the species that are seen within veterinary practice.

Canine stress signals

Beerda et al (1997, 1999, 2000) carried out a number of studies that looked at how dogs reacted to a perceived aversive stimuli. These studies correlated behaviours with physiological responses to a stressor such as raised cortisol levels and raised heart rate. These behaviours are indicators that a dog is not comfortable with a situation, or finds a situation potentially threatening. A list of these behaviours, along with other behaviours that may indicate a dog is struggling within a situation can be found in Table 1.

|

|

Feline stress signals

As with dogs there are certain behaviours that indicate that a cat is finding a situation stressful or difficult to deal with. These behaviours have been studied within veterinary environments and correlated with physiological SR such as raised heart rate. These behaviours have also been seen in responses to restraint/handling and situations that may be viewed as obviously stressful. These behaviours are detailed in Table 2.

|

|

In 1997 Kessler and Turner carried out a study into the feline SR within certain environments such as rehoming shelters. To test the levels of stress within the cats a series of observational non-invasive criteria were developed. These are now used as a tool in measuring a feline SR without having to interact with the animal. This may be useful for staff members when identifying SR in feline patients within the waiting room, and to pass on to owners so they can identify SR within their own pets and take appropriate action. This Cat Stress Score test, based on the data given during Kessler and Turner's 1997 study, is displayed in Table 3 (Kessler and Turner, 1997).

| Score | Body | Stomach | Legs | Tail | Head | Eyes | Pupils | Ears | Whiskers | Vocal | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fully relaxed | Laid out on side or back | Exposed, slowventilation | Fullyextended | Extended or loosely wrapped | Laid on surface with chin up or on surface | Closed or opened, may be blinking slowly | Normal | Half back (normal) | Lateral(normal) | None | Sleeping or resting |

| 2. Weakly relaxed | I. laid vertically or half on side or sittingA. standing or moving, back horizontal | Exposed or not, slow or normal ventilation | I. bent, hind legs may be laid out. A. when standing, extended | I.extended or loosely wrapped A. up or loosely downwards | Laid on surface or over the body, some movement | Closed, halfopened or normal opened | Normal | Half back or erected to front or back and forward on head | Lateral or forward | None | Sleeping, resting, alert or active, may be playing |

| 3. Weakly tense | I. laid ventrally or sittingA. standing or moving, body behind lower than front | Notexposed, normalventilation | I. bent A. when standing, extended | May be twitching I. on the body or curved backwa rds A. up or tense downwards | Over the body, some movement | Normalopened | Normal | Half back or erected to front or back and forward on head | Lateral or forward | Meow or quiet | Resting awake or actively exploring |

| 4. Very tense | I. laid ventral, rolled or sitting A. standing or moving, body behind lower than in front | Notexposed, normalventilation | I. bent A. when standing, hind legs bent in front extended | I. close to the body A. tense downwards or curled forward, may be twitching | Over the body or pressed to body, little or no movement | Widely open or pressed together | Normalorpartiallydilated | Erected to front or back, or back and forward on head | Lateral or forward | Meow, plaintive or quiet | Cramped sleeping, resting or alert. May be actively exploring trying to escape |

| 5. Fearful, stiff | I. laid ventrally or sittingA. standing or moving, body behind lower than front | Notexposed, normal or fast ventilation | I. bent A. bent near to surface | I. close to body A. curled forward close to body | On the plane of the body, less or no movement | Widelyopened | Dilated | Partiallyflattened | Lateral or forward or back | Meow, plaintive or quiet | Alert may be actively trying to escape |

| 6. Very fearful | I. laid ventrally or crouched directly on top of all paws. May be shaking A. whole body near to ground, crawling, may be shaking | Notexposed, fastventilation | I. bent A. bent near to surface | I. close to the body A. curled forward close to the body | Near to surface, motionless | Fullyopened | Fullydilated | Fully flattened | Back | Plaintive meow, growling, yowling or quiet | Motionless, alert or actively prowling |

| 7. Terrified | Crouched directly on top of all fours, shaking | Notexposed, fastventilation | Bent | Close to the body | Lower than the body, motionless | Fullyopened | Fullydilated | Fully flattened back on head | Back | Plaintive meow, growling, yowling or quiet | Motionless |

The importance of recognising stress

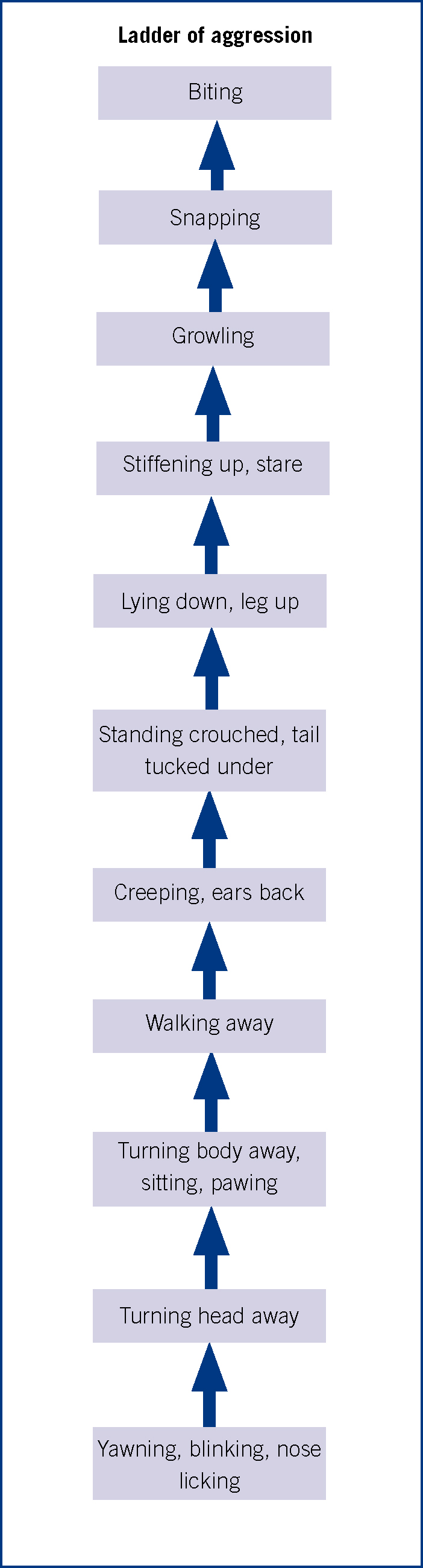

If an animal is in an aroused state, such as when responding to an environmental stressor, then there is an increased likelihood of that arousal progressing into aggression. An animal may find a situation or environment stressful, this can evoke an emotional response such as anxiety or fear and progress to aggression quickly if the situation or environment are sufficiently stressful and aversive. This can be seen by looking at the ladder of aggression designed by Kendal Shepherd (Shepherd, 2009). An interpretation of this can be seen in Figure 1.

It is clear to see by looking at the ladder how an animal can progress from the lower levels of anxiety up to the extremes of fear and aggression. If a patient is already two or three rungs up the ladder before they enter the consultation room the likelihood that they may progress to aggression is potentially increased. The aim is to keep patients as low on the ladder as possible throughout the time spent in practice. This not only increases the patient's positive associations with the veterinary practice, which is beneficial for subsequent visits, but also improves safety of all involved.

A study of veterinary staff in Australia revealed that the majority of physical injuries reported were due to dog/cat bites/scratches (Jeyaretnam et al, 2000). One further study analysed data from a 5 year period of accident claims. These came from up to 10 000 practices incorporating up to 27 500 veterinary staff. An average of 2000 claims per year were made and roughly 66% of these claims were due to bites, scratches or kicks from patients (Nienhaus et al, 2005). This was then reiterated in a 2006 and study that stated 87 of 228 veterinary staff that responded had been bitten by a dog in practice (Wake et al, 2006). These studies highlight how important it is to reduce SR within the practice, and thereby potentially reduce the risk of bites within the practice environment.

Prevention

Providing owners with advice on ways to provide their pets with positive associations of the veterinary waiting room is one way to reduce the SR those animals experience when exposed to the waiting room environment. Advising owners to enter the practice outside of a consult situation, have staff pet them and give them treats and have a good experience of the waiting room will aid in a reduced SR in subsequent visits. This may be done prior to a problem being noticed, as a precaution or with a dog that struggles with the environment already to help ease anxiety.

With feline patients giving owners advice on how to offer the cats positive associations with the basket is a good way of reducing SR.

Within the home environment the owner can keep the basket out and create positives to pair with it. This can be done by allowing the cat or kitten to sleep in the basket, feeding them within the basket and playing games in and around the basket (Vogt et al, 2010).

Some owners or professionals may muzzle the dog for veterinary visits. The muzzle itself can cause the dog to experience some anxiety. The muzzle is a potentially novel stimuli that restricts the dog's reactions. To reduce the anxiety associated with the muzzle offering pleasant associations with it may help. This can be achieved by using the muzzle at home and in environments away from the veterinary clinic where the dog is calmer. Placing the muzzle on while the dog is lying with the owner in the evenings or at intervals during the day may be beneficial. Using a muzzle that allows the owner to give treats while the dog is wearing it is also beneficial. Bowen and Heath (2005) state it may aid the process to smear something tasty such as peanut butter at the end of the muzzle to improve associations and aid in putting on the muzzle. This allows the dog to make the choice to place their nose into the muzzle. This will reduce the dog's anxiety as it is not being forced into wearing the muzzle, rather it is a voluntary action on the dog's part.

Veterinary socialisation classes

In addition to clients bringing their pets in outside of a consultation setting practices can also offer veterinary socialisation classes. These classes can be designed to not only offer positive associations with the practice waiting room, but also to different equipment and handling that may be used during a consultation. Appropriate and pleasant socialisation during the animal's sensitive periods (4–12 weeks in dogs, 3–7 weeks in cats) can help prevent fear/anxiety-based problem behaviours occurring. It has been suggested that doing this within a veterinary environment may help prevent future problems (Hetts et al, 2004).

This is furthered by looking at a 2008 study, where dogs' SR levels were assessed during their time in the veterinary waiting room. The study highlighted that dogs who had previously visited the practice showed an increased SR when compared with dogs that were on their first visit (Hernander, 2008). This highlights how prior experience can effect a patient's response to a stimuli. If the patient has had positive experiences of both the practice and stimuli within the practice this may mean subsequent exposure is improved.

Socialisation classes should consist of working with various aspects of the practice such as medication administration, the consultation rooms and tables as well as handling techniques. This should be introduced gradually and paired with positives. Giving owners the tools to do this at home between classes will also be beneficial. By allowing the patient to predict a positive, pleasant outcome from a situation there will be a reduced SR. Offering the patient positive associations with all different aspects of the practice reduces the likelihood of a novel stimuli causing a negative reaction during a consult, which may then result in a SR during subsequent visits (Mills et al, 2013). Prevention of a SR occurring via offering socialisation classes may be a very useful aid when combating waiting room stress.

Layout

There are certain adjustments that can be made to the layout of the practice waiting room as a precaution that may be beneficial in reducing SR for patients. By creating a well-designed waiting area the number of stressors that patients come into contact with can be reduced (Mills et al, 2013). One option is to have separate cat and dog sections where they cannot interact or see each other (Figure 2) (Johnson-Bennett, 2007). If this is carried out there may be further benefit in creating a separate entrance for each section to avoid having to transport cats through a noisy canine section, or walk a canine through a feline section (Harvey, 2007). It may be beneficial to design an outside area for dog owners to wait in, or advise waiting in the car until the appointment time if the waiting area is not big enough to provide separate sections or using an unused consult room for feline patients (Harvey, 2007).

This design may also allow patients the chance to get away from, or hide from, stressors. One of the recognised signs of a stress response in both feline and canine patients is hiding. In her book The Cat: Clinical Medicine and Management Susan Little states that offering a hiding place for cats can help to reduce the SR (Little, 2011). One suggested option is installing shelves or elevated platforms for cat baskets to avoid having them on the floor or on chairs. If cats are placed in elevated positions other animals cannot approach, which may be beneficial in reducing feline anxiety (Norsworthy et al, 2011; Bassert and McCurnin, 2013). This may also be beneficial for reducing anxiety in other species, such as rodents.

From the author's experience when teaching in a training class environment it is often beneficial to space out the seats so that clients and dogs are not within close proximity to each other. This helps to reduce stress and offers each dog their own space. This concept may have a positive effect on veterinary waiting rooms offering individual space to patients.

Finally, it has also been suggested that the décor and environment of the waiting room needs to be considered, for example keeping the area as quiet and calm as possible, potentially moving a telephone area as far from the seating area as possible and taking into account the lighting within the room. Flickering lights may affect patient SR levels (Mills et al, 2013). Décor may also need to be considered; using statues of dogs, painted animals on the wall etc may look appealing but could cause stress to patients (Mills et al, 2013).

These precautions depend on the space available and may not be attainable in every practice, however if your practice is able to modify the layout of the waiting room this has the potential to help reduce stress.

Adjunctive's within the waiting room

There are certain added extras that can aid with stress reduction and can easily be implemented within the veterinary environment. These include extras that can be placed into the environment to support the other changes discussed in this article.

Pheromone therapy

Pheromone therapy has been shown to have stress alleviating effects in both canines and felines. This form of therapy utilises natural chemicals released by animals that have calming or relaxing effects.

For canine patients dog appeasement pheromone (Adaptil, Ceva) is widely used. This pheromone is produced by a nursing female to calm or reassure her puppies and has been shown to be successful in aiding stress reduction in a number of studies (Tod et al, 2005; Gautier et al, 2009), such as when used alongside a behaviour modification programme to reduce fear and anxiety in relation to fireworks (Levine et al, 2007).

The Tod et al (2005) study looked at how effective Adaptil was in reducing stress behaviours within a rescue centre environment. The study concluded that the use of Adaptil successfully reduced some, but not all, of the behavioural signs of stress. One study showed that the use of a Adaptil collar on puppies reduced fear-related behaviours when confronted with strangers and new environments (Gautier et al, 2009).

The veterinary environment is often a new or novel environment for patients as they are rarely exposed to it, and studies have shown the effectiveness of Adaptil within this environment (Kim et al, 2010; Mills et al, 2006). Kim et al conducted a study into the reduction of separation anxiety-based behaviours while hospitalised in a veterinary practice. The study showed that the use of Adaptil is effective in reducing anxiety and distress in canine patients (Kim et al, 2010). Mills et al also identified that dogs’ body language appeared more relaxed within the waiting room when a Adaptil plug in diffuser was used (Mills et al, 2006).

This research identifies that Adaptil can be a useful adjunctive to aid stress or anxiety relief in dogs. It has been seen to be useful in a number of environments, including the veterinary waiting room.

In felines Felifriend and Feliway (Ceva) are used for pheromone therapy. These are chemicals that are released when cats rub their heads on objects/animals/people. Within these there are five functional fractions (F1–F5). Feliway and Felifriend are artificially synthesised versions of F4 (Felifriend) and F3 (Feliway).

Feliway is used to provide the cat with a sense of ease and relaxation when exposed to stressful environments or situations. It is often used with patients that are suffering from feline idiopathic cystitis to reduce stress, as stress reduction is one of the ways to manage illness. One 2004 study showed that patients that were exposed to Feliway showed a reduced number of days displaying clinical signs, including behavioural traits such as aggression and fear; these are behavioural traits that may also be experienced within a waiting room setting (Gunn-Moore and Cameron, 2004).

In addition, Feliway has been seen to reduce spraying behaviour (Landsberg et al, 2013). This is a behaviour that is associated with stress. One longitudinal study looked at 43 cats that displayed spraying behaviour. These cats were treated with Feliway and within 4 weeks of treatment 91% had shown a reduction in spraying behaviour prevelance compared with at the beginning of the treatment, 10 months later, six cats were not spraying at all, 27 were still spraying at a reduced level than they were at the start of the study, seven were the same and three had deteriorated (Mills and White, 2000).

F4 is used to reduce the stress of being exposed to an unfamiliar individual or individuals. Although its use has been seen to be beneficial within a consulting/handling situation (Mills et al, 2013) its use in a waiting room is minimal. This is because it is most effective when sprayed on the hands of the unfamiliar individual, rather than within an environment.

It is worth noting, however, that the results of pheromone therapy are variable with one review stating that only two out of 14 reports provided viable and significant results (Frank et al, 2010). Mills et al (2013) also state that reports of Adaptil working within the veterinary setting are mainly anecdotal. It is therefore advised that pheromone therapy is used to compliment other, more effective measures, such as practice layout and preventative measures, rather than as a solution on its own (Mills et al, 2013). It is also noteworthy that the use of Felifriend should ideally only be used during a cat's first exposure to the veterinary environment to avoid any conflicting response between the pheromone message and the visual message, which could increase the SR rather than decrease it; the pheromone message would be ‘saying’ that the environment is safe, while the visual message would be saying that the environment is threatening, based on prior experience.

Olfactory stimulation

Studies have shown that certain scents result in an increased presentation of calm behaviours. The majority of studies into olfactory stimulation have been conducted in dogs. These studies have highlighted that offering lavender scent in a situation that may evoke a stress or anxiety-based response may result in calmer behaviours.

Graham et al (2005) found that the diffusion of lavender oil into a rescue centre environment resulted in relaxed behaviours such as more time spent resting and reduced vocalisations (Graham et al, 2005). Wells (2006) also found that if there was an ambient odour of lavender in the car, dogs that had a history of travel-induced excitement spent more time resting and displayed reduced vocalisations compared with in the absence of lavender (Wells, 2006).

These studies highlight how adding lavender scent into the waiting room may aid in promoting relaxed behaviours and reduced vocalisations within the veterinary waiting room. This may then help to promote a calm and relaxed waiting area.

There have been minimal studies into the effects of olfactory stimulation on cats. One study showed that catnip elicited positive behaviours such as pawing and playing (Ellis, 2007). Offering owners catnip toys to place in the cat basket may be a useful adjunctive to providing a more positive environment for pets in the waiting area.

As with pheromone therapy it is important to recognise that olfactory stimulation and enrichment is not to be used as a solution. It may aid in reducing some stress-related behaviours however the best results will be seen when it is used in conjunction with other more practical solutions such as those highlighted in this article.

Auditory stimulation

Offering certain types of auditory stimulation has been shown to aid in stress reduction within stressful environments. Classical music has been seen to promote relaxed behaviours such as decreased barking and increased resting (Wells, 2004). This has recently been re-iterated by a study in 2012 that looked at the effects of playing music into a kennel environment. The results showed that classical music resulted in an increase in relaxation behaviours and reduced vocalisation behaviours compared with the use of no music and other types of music, including heavy metal (Kogan et al, 2012). There are no studies that provide information on the results of auditory stimulation for cats.

As one of the stress inducing stimuli for cats may be canine vocalisations, using classical music to aid in the reduction of canine vocalisations may in turn aid in the reduction of stress for feline patients.

Owner advice

There are certain measures that owners can take prior to entering the practice that can aid in reducing the SR in their pets. It has already been mentioned that prior training can aid in stress reduction, however this section looks at more adjunctive methods that can be applied prior to entering the practice.

Pheromone therapy has been discussed within a practice setting using plug in diffusers. Both dog appeasement pheromone and Feliway also come in spray form. This means a dog's collar or a bandana tied around the dog's neck can be sprayed with Adaptil. It is important to note that if this is bieng done it is important to spray the collar or bandana (ideally a bandana) 20 minutes before it is placed on the dog to avoid skin irritation. There are also Adaptil collars on the market.

This may be furthered by the owner applying lavender oil to the tips of the dog's ears prior to entering the practice. This has been seen to reduce heart rate in dogs (Komiya et al, 2009).

A cat's bedding used within the cat basket can be sprayed with Feliway. Not only will this provide a more localised distribution of the pheromone but it will also aid in reducing the animal's stress and anxiety levels on the journey to the practice.

It has been suggested that petting and gentle massage are a useful method of promoting relaxation and relaxed behaviours in dogs within a kennel environment (Hennessey et al, 1998). It is worth noting that the method by which massage or petting occurs is also important; positive results were gained using long firm strokes from head down to the dog's hindquarters. This can also have an effect on the owner. Petting can reduce blood pressure and aid in keeping pets calm and relaxed while sitting in the waiting room (Vormbrock and Grossberg, 1988). This may have a follow on benefit in reducing the anxiety level of the pet.

There are also benefits for feline patients. Rodan (2010) suggests that the owner massaging the cat around the head can reduce anxiety. Massage or petting of the animals while in the waiting room can be advised, and can aid in reducing stress for both the animals and the owners.

One final piece of advice to give owners is how to recognise that their animals are stressed or uncomfortable. Owners may be aware of the more pronounced behaviours that indicate stress but not of the earlier and more subtle signs (Mariti et al, 2012). It may be beneficial to highlight these behaviours prior to the appointment as well as making sure staff are aware of them. If staff working on reception are aware of stress-related behaviours they may be able to notice them before the owners and offer advice. Pictures and diagrams in the waiting room outlining common stress-related behaviours and methods to reduce them may also be beneficial.

Conclusion

There are a number of steps that can be taken to reduce stress within the veterinary waiting room. These range from the layout of the waiting room itself to pre-emptive tactics that can be implemented prior to entering the practice. It is important to reduce stress within the waiting as this will then have a follow on effect within the consultation room and for subsequent visits to the practice.