In practice, the veterinary nurse (VN) has a wide role to play ensuring that they are aware of the legal, professional and ethical ramifications of any decisions they make or actions they take (Orpet and Welsh, 2011). Since becoming a regulated profession in 2007, VNs are accountable for their conduct and subject to the standards set by the Veterinary Nursing Council which relates to the Veterinary Surgeon Act (1966) where for example, only veterinary surgeons are permitted to make a diagnosis (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2016a and b). The VN is authorised to inform the owner of any clinical symptoms the animal is displaying, such as weight loss, poor coat condition, or skin problems and then advise what the next steps might be, which is usually a consultation with the veterinary surgeon (Ackerman, 2012). It is therefore the duty of care of VNs to ensure that owners are educated and supported to a level that prevents such conditions impinging on their animal's quality of life, and causing unnecessary suffering (McLeod, 2008).

There are many types of clinics VNs can run without a veterinary surgeon, examples of which can be seen in Box 1. For those nurses that like to run clinics, knowledge and skills can be encouraged, for example in organising and running special monthly promotions, nutrition clinics and socialisation classes. A nurse that shows enthusiasm for helping and educating is ideal (Tottey, 2015) as these clinics will not only provide care for the patients involved, but also for the owners of the patients (Orpet and Welsh, 2011), which will in turn encourage better pet owner responsibility and care. Less experienced nurses should participate in all clinics to help build confidence and develop an understanding of the elements involved (Tottey, 2015) by beginning with basic clinics, but also by being involved with the more in depth clinics, shadowing an experienced nurse. This type of development is important for growth in the nursing profession on a personal basis, but also for practice growth, so that all nurses within the team are able to deliver educational nursing clinics.

Being able to run nurse clinics allows VNs to use skills and apply knowledge to lots of different situations, not only strengthening the bond between client and nurse, but also between patient and nurse. Both of these bonds are very important for different reasons. Yeates (2014) reported that nurses have a wide role to play with clients, which helps the client fulfil their responsibilities to their pet. The end result helping both owner and animal. Also, Yeates (2014) suggested that clients are often more willing to disclose information to VNs, either because they might be embarrassed to discuss it with the veterinary surgeon, or feel that they are wasting the veterinary surgeon's time.

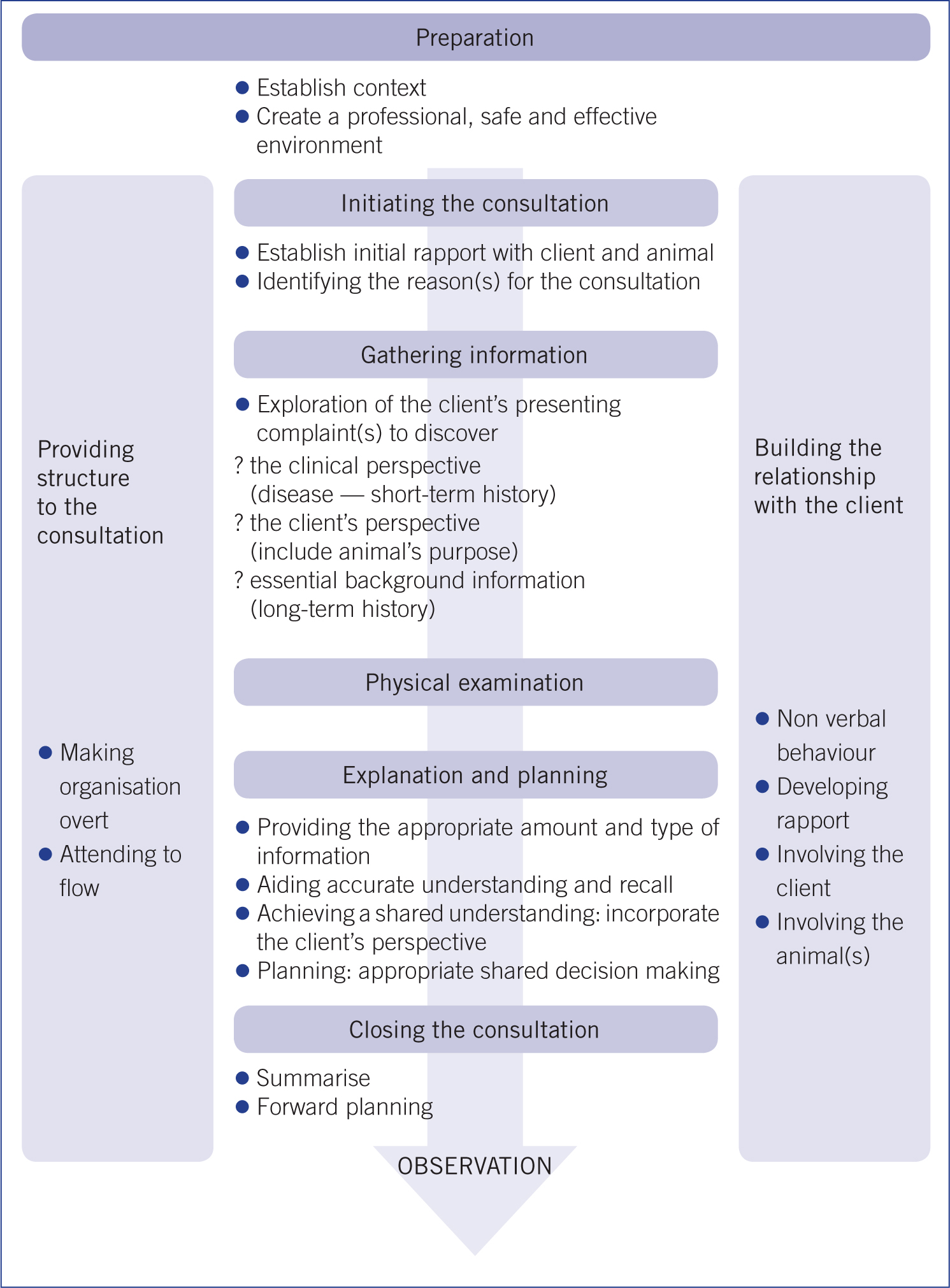

Nursing clinics can follow a standardised format. Figure 1 shows the Cambridge-Calgary consultation model, which has been adapted by the National Unit for the Advancement of Veterinary Communication Skills (NUVACS), making it relevant to the veterinary profession (Ackerman, 2012). The clinic leading VN can use the model to ensure adequate information is gathered, explored and fed back to the client in the correct way by using the structure. The model proves relevant to the nursing profession and can be expanded on and set out in relevant stages allowing a clear understanding of the information passage between both client and nurse during the clinic. This model can be applied to all nursing clinics, and is a good reminder of how clinics can be successful, ensuring effective communication. The five sections allow the clinic to have form and structure, rather than appearing random or disorganised to the client. Models such as this are useful tools that allow each individual to explore and improve their own consultation style. It is important, however, that the clinic is run in a fashion that is personal to the individual nurse (Radford, 2009).

Benefits of nursing clinics

Nursing clinics provide a lot of benefits to all involved. VNs derive high levels of job satisfaction from being able to use their knowledge and skills to a higher level (Harris, 2012) to assist in improving the VN/client/patient bond, providing educational preventative healthcare to clients, allowing the patient to come to the practice in less stressful circumstances therefore giving the VN time to spend developing a personal and professional relationship. Most often, nursing clinics are free of charge to clients, which promotes the practice by increasing the chance of word of mouth referrals, leading to more clients and, potentially, improving financial remuneration (Harris, 2012). Veterinary surgeon consultations can be more time restricted compared with nursing clinics, and often the client feels uncomfortable questioning the veterinary surgeon (Tottey, 2015), especially if feeling pressured to leave. By having nurse clinics, clients may perhaps feel a little more at ease to discuss various concerns/ask advice rather than using up the veterinary surgeon's time. Having opportunities to promote other services the practice has to offer will also present itself during most nursing clinics as conversation occurs.

Preparation

Preparation is key to running a successful nursing clinic. Knowing what consultations are booked in advance is essential, as necessary equipment and materials need to be organised, examples of which can be seen in Box 2. It also allows for the nurse to read the history and fully prepare for each individual client and pet, however there are occasions when the reason for the consultation can change, but this only becomes apparent when the animal is presented (Ackerman, 2012). For example, a dental check could also have the need for anal gland expression or a nail clip without the VN being aware, so by having extra suitable equipment for most common requests available, the VN can be prepared for most eventualities. Practice product and service knowledge is a must (Tottey, 2015) such as being aware of parasite prevention, counter sale ear cleaners or shampoos, and to be able to answer any client questions in a competent manner.

The environment in which the clinic is being conducted should have a relaxed and easy feeling. If there is a computer in the room, angling the screen and keyboard to face the client, while checking their notes/history will ensure you are not ‘cutting off’ communication by facing away (Mayne, 2011). Other things such as standing on the same side of the examination table as the client when possible, or sitting with them if they sit, will allow a more personal and private approach. Rearranging the consultation room to suit the patient and the client needs can also be beneficial.

Consultation length needs to be suited to the individual practice, but generally should be about 10 to 15 minutes long. For more indepth clinics such as adolescent and senior checks, allowing 20 minutes will provide extra time to obtain a full history and physical examination, and allow a thorough conversation about any issues and still have enough time to either solve these issues or suggest solutions. Monitoring effects of these timings could help to determine whether consultation length is associated with improved patient care, owner satisfaction and financial benefits for the practice (Robinson et al, 2014).

Additional equipment can often reduce stress for the patient during the visit to the surgery, such as pheromone sprays and plugin phermomone adapters. These can be placed in the waiting area and in the consultation room. Dogs and cats quickly learn to associate frightening or painful experiences with the surgery and staff (Lloyd, 2014), and therefore trying to make their visit as comfortable as possible is vital.

Many clients like to see the VN who they are familiar with, or who has been seeing their pet for other clinics. This links to patient/client/nurse continuity and is a good protocol to have in practice if staffing allows it. This can be enforced by booking the next appointment at the end of the consult.

The clinic

Following the adapted Cambridge-Calgary model, a full understanding of client and patient needs is critical when beginning any clinic. Getting to know the patient and their temperament, especially if new to the practice, is a step that occurs automatically in most clinics. Petting dogs when they arrive, and allowing cats to come out of their carriers in their own time, will allow the VN to get a feel for their patient. Ackerman (2012) suggested that owners think of their pet as part of the family, and this special bond needs to be respected.

The next step is the examination and information exchange. The VN must be able to carry out a basic physical examination and be able to recognise normal and abnormal clinical signs in the patient (Figure 2) (Orpet and Welsh, 2011). This step allows the client to focus on the main reason for being at the clinic. Clear speaking, and a steady talking pace is needed, and always avoiding the use of jargon and veterinary terminology. Some clients will understand certain terminology, especially if they themselves are from a medical background, however, by keeping it simple to start with, the VN can gauge the client's own knowledge and understanding.

In the adapted Cambridge-Calgary model, the explanation and planning section is separate to that of the physical examination. Often in clinics, these two sections merge together and while examining the patient, explanation can be taking place also. This can be more beneficial to the client rather than splitting each section up. For example, when running an adolescent health check clinic, if checking the dental status of the patient, the VN can show and describe what is being looked at. At wound check-up clinics, it is beneficial to get the client to look at the wound at the same time, so that the VN can discuss the wound status. This education of the client is also of benefit, because it enables the owner to act quickly in the case of deterioration.

Closure

Closing the consultation requires a re-cap of the main points raised in the clinic. This not only reinforces advice, but also allows the VN time to ensure the owner has fully understood what was discussed. Asking if the owner is happy and have everything they need, will provide verbal confirmation. Closed questioning is best suited at this stage, as this should show that the client's original expectations of the consultation have been met (Ackerman 2012). Finally, writing down future appointment times, with the VN's name, will provide full closure to the consultation.

Financial benefit to the practice

Veterinary practices should be continually mindful of costs and expense controls (Chamblee et al, 2010) so any kind of profit is a gain to the practice and this can be made from nurse clinics through the advice provided by the VN. Discussion of parasite prevention can lead to the client purchasing treatments, weight clinics can lead the client to buy a suitable diet from the practice (Figure 3), and adolescent health checks can lead to neutering surgery, microchipping and endless other services. Although many nurses may not think of themselves as sales personnel, it is something that naturally occurs during nursing clinics. By nurses recommending products or diets, the client may be willing to spend money because they believe the nurse is offering the best care for their pet.

Charging for nursing clinics is a matter of practice protocol. It is important that a value is placed on the nursing team as qualified professional members of the practice, and they deserve recognition from both clients and veterinary surgeons (McLeod, 2008).

Conclusion

Nurse clinics are an excellent way to bond with clients and encourage loyalty to the practice while offering a multitude of opportunities to generate income for the practice (Guthrie, 2009). Whether this is incidental income from providing preventative healthcare measures, or from senior health checks that then require veterinary surgeon assistance and tests, it is income that benefits the practice and ensures that all patients get the best possible, gold-standard care from the veterinary team.