Control of infection within a practice or hospital environment is probably one of the single most important roles of the veterinary nurse. The best possible care should always be given to patients and so ways to reduce or eliminate the risk of spread of infection should be implemented. From admission to discharge there are many points at which there is a risk of infection; at any stage infection can be detrimental to the welfare and recovery of the patient.

It is useful to be familiar with a number of well used terms (Blood, 1988):

Whose responsibility is hygiene in the practice?

Everyone in the practice, owner/client, veterinary surgeon, veterinary nurse, receptionist, kennel worker/patient care assistant and cleaner is responsible for hygiene of the practice. It is everyone's responsibility as there are a number of repercussions if practice hygiene is not adhered to. Clients and practice staff expect:

Admission — before the patient reaches the front door

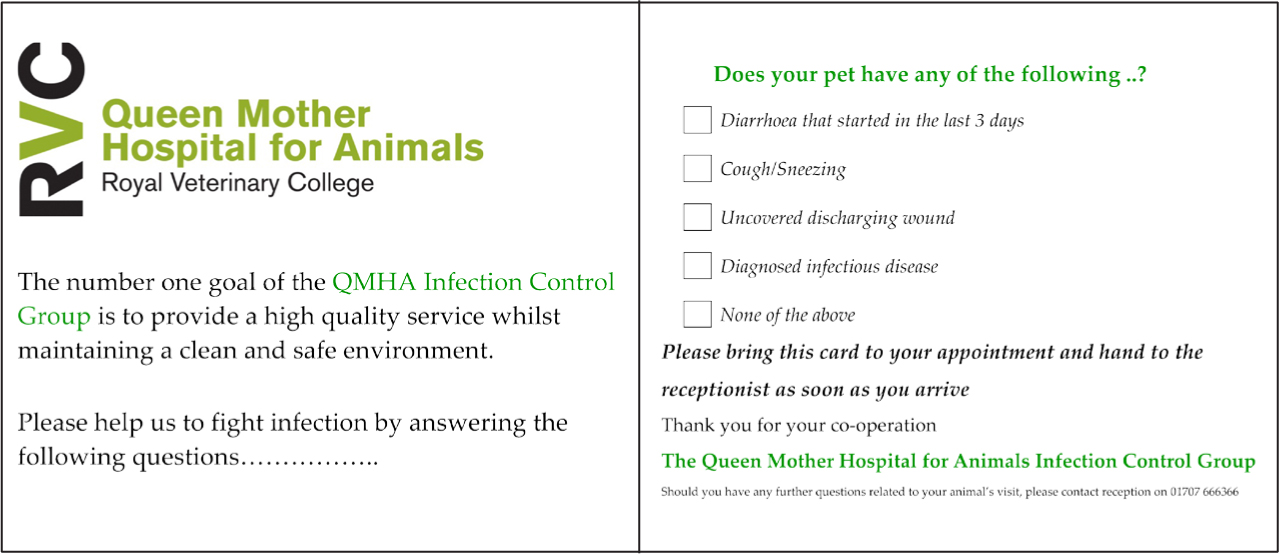

A large proportion of the patients coming into the practice or hospital do have a pre-booked appointment. During a booking telephone call with an owner, it would be prudent to check that the animal is not suffering from any potential infectious disease, for example vomiting, diarrhoea, coughing, sneezing or has an open wound (Figure 1). If suspicion arises that the patient may infectious, the owners should be questioned further before the appointment is organised. It may be advisable to have them wait in the car until their appointment, book the last appointment of the day, or bring them into the practice through another entrance to prevent infection of other patients in the waiting room by direct contact transmission (Anderson, 2008). Vaccination, including that for kennel cough, may be advocated for patients visiting the practice or being hospitalised. Personnel involved in answering the telephone and dealing with owners need to have adequate knowledge and training with the ability to assess and identify any potential infectious cases.

If an infectious patient is admitted to the practice:

In larger practices and hospitals it may be possible to have a separate isolation consulting room for patients with a potential infectious disease. It is important that the room is correctly cleaned between patients. If this cannot be carried out immediately, due to the ongoing treatment of the patient, then it should be clearly signed highlighting the potential presence of an infectious agent to ensure no one else uses the room for another patient prior to a full clean as per the practice's guidelines (Figure 2).

This pre-planning is not possible for all cases. Those that present as emergencies without prior warning are difficult to triage, especially with other life threatening conditions that must take priority. Often management of these areas has to be completed after the event.

Hospitalisation

Infections are considered hospital acquired if they occur within 48 hours of admission or within 30 days after discharge (Binns et al, 2014). The prevalence of HAIs for the veterinary patient is unknown. It is difficult to determine where the patient was exposed to the infection — unless every patient entering the practice is swabbed and results indicate that the infective agent was present in the practice, it is not possible to say for sure it was acquired within the hospital setting. It is also very unlikely that it will be possible to completely eliminate HAIs, however, it is important to reduce the risk of acquiring an HAI as much as possible. Using separate areas for hospitalisation of infectious patients, including a specialist isolation ward, can be very useful. If a whole ward for isolation is not available, or unrealistic such as in a small practice, the patient can be housed in a kennel or cage away from the other patients and barrier nursed (see later section) (Figure 3). Separate equipment should be stored and labeled and only used in the isolation area. Thermometers, pens, stethoscopes, leads, clipper blades (disposable) and scissors should all be cleaned, disinfected and sterilised in between use (Figure 4). Leads, clipper blades and scissors should be sterilised with steam in an autoclave. Other items should be sterilised using ethylene oxide or gas plasma sterilisation (hydrogen peroxide) if available.

Separate, different coloured, bedding can also be used in infectious cases to identify it from other bedding to prevent its use in another area. Bedding should not be trailed through the ward area to the laundry area but bagged and sealed at the cage; once used, gross contamination should be removed and disposed of and the bedding should be placed in sealable bags, and double bagged if necessary. Washing bags that disintegrate in the laundry can be used to help contain any contamination (Figure 5). These are a good way to transport dirty laundry and prevent it contaminating other areas of the ward, especially if they have to wait to be washed. Bedding should be washed in a hot water cycle (>71°C) for 25 minutes with an appropriate disinfectant (Portner and Johnson, 2010). Bedding should never be washed in the same machine as other theatre textiles such as drapes and scrub suits to prevent contamination with hair and debris.

Hygiene protocols

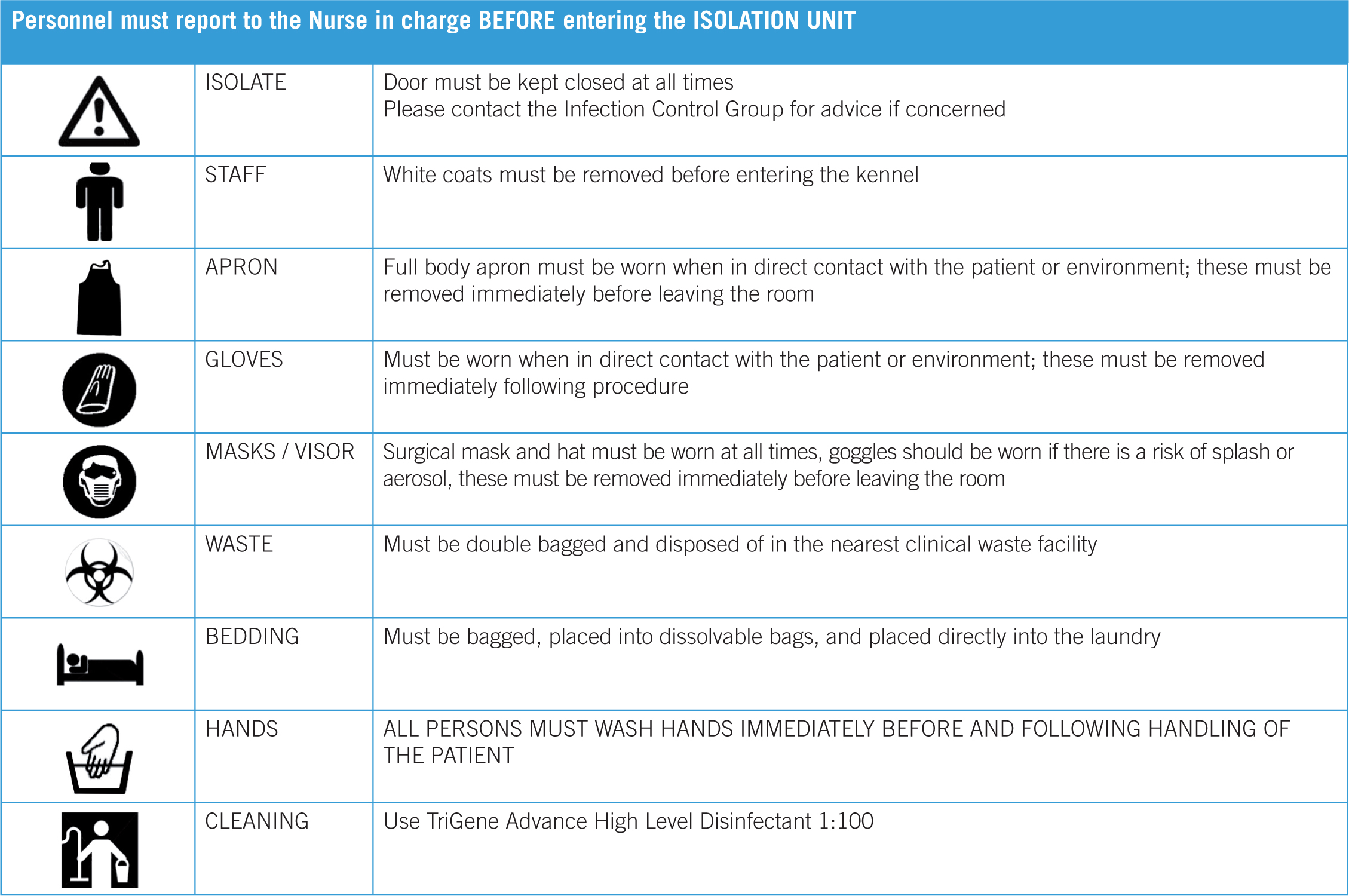

Isolation is not a failsafe way to prevent cross infection of patients. The correct protocols need to be written and followed. These protocols should ideally be written by someone in the practice who is part of an infection control group. They should have a keen interest in infection control and be up-to-date with changes and guidelines from relevant literature. All personnel in the practice should be trained in the correct use of personnel protective equipment (PPE) and the protocols when caring for infectious cases, and entering and leaving an isolation area. The minimum PPE required depends on the case being cared for, some suggested guidelines that the authors practice use in barrier nursing and isolation cases are listed in Table 1.

| Potentia infectious disease | Example | Personne Protective Equipment Require |

|---|---|---|

| Zoonotic dermatologica disease | Ringworm | Uniform |

| Respiratory infectious disease | Cat flu (Calici virus, Feline herpes virus) kenne cough (Bordetella bronchisptica) | Paper boiler suit over uniform |

| Multi drug-resistant bacteria infection (wounds etc.) | Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli | Paper boiler suit over uniform |

Hand hygiene

Improving hand hygiene contributes significantly to the reduction of HAIs (Pratt, 2007). Regular, thorough, hand hygiene is essential to reduce the spread of micro-organisms. Adopting a ‘bare below the elbows policy’ with all staff and visitors wearing short sleeved uniforms a lows the hands, wrists and forearms to be washed regularly. Other considerations include nails being kept short and free from nail varnish and no rings or wrist-watches as these can harbor bacteria and inhibit a good hand wash technique (Arrowsmith, 2001). Techniques may vary between practices and many practices use the basics from the World Health Organisation (WHO) Guidelines on Hand Hygiene — poster (2009) to show employees and visitors a pictorial version (http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/How_To_HandWash_Poster.pdf?ua=1). There are a number of product options when hand washing and the availability of them depends on the practice. Alcohol rubs, chlorhexidine, iodine and iodophors and plain non-antimicrobial soaps are some of the most common. The most important factor in washing hands successfuly is the use of the correct technique and ensuring the correct contact time for the product that is being used. The author's practice uses a combination of a pH neutral soap to remove gross contamination and an alcohol rub for a hygienic hand cleanse between patient contact.

The WHO guidelines (2009) recommend the following: ‘At present, alcohol-based hand rubs are the only known means for rapidly and effectively inactivating a wide array of potentially harmful microorganisms on hands’ (WHO guideline (2009) Section 12.1, page 49). However, having the correct protocol is not a guaranteed way of preventing transmission of infection; each healthcare worker must ensure the correct application is carried out each and every time.

To encourage re-application of hand rubs, dispensers should be available at multiple points around the practice. These also need to be disinfected regularly to prevent them being a source of transmission themselves. They are often situated around the practice with signs encouraging everyone, including pet owners, to use them.

Regular training, especially if new products are introduced, of staff and visitors is important and necessary. It is very easy to become complacent in thinking everyone knows how to wash their hands. Training can include a special dye within the product or applied to the hands to test people's hand washing techniques. For the first method the special solution is within the alcohol rub and the second the spray is placed on the hands before a standard hand wash is performed. For each the hands are placed underneath an ultraviolet light and any areas that have not been effectively cleaned show as bright areas. Training sessions for everyone using this method should be regularly planned and feedback given.

Barrier nursing

Barrier nursing is a method of nursing care that involves tending infectious patients in isolation, to prevent the spread of infection (Collins English Dictionary). It includes the use of infection control procedures to control the spread of pathogenic organisms to patients and vectors throughout the hospital. There are several reasons for barrier nursing patients for infection prevention and control purposes:

There can be varying levels of barrier nursing depending on the case involved. In each case the type of suspected infection should be written on a sign on the front of the patient's cage to alert all members of the veterinary staff (Figure 6). PPE should be located nearby for all personnel involved with the case to wear when handling the animal and should usually include a disposabe long-sleeved plastic apron, vinyl/nitrile disposable gloves and shoe covers. It may also include a facemask or goggles depending on the patient and the potential disease transmission process. Infectious diseases that require facemasks and/or goggles include canine kennel cough, cat flu, feline and canine revirus and feline tuberculosis. Limited data are available on the efficacy of footbaths; when used they should be placed just inside the door of the isolation area and used before departing the room (Morley, 2005).

Barrier nursing is only effective if everyone adheres to the rules. Barrier nursing does not involve everyone wearing PPE and continuing to touch everything! A person should be allocated to be ‘hands on’ with the patient while wearing PPE, and a second person to work equipment, collect materials and make records. The second person should wear PPE but not physically touch the patient to prevent transfer to the environment.

Any special/additional instructions need to be written as a protocol in clear concise bullet points. Nurses involved with any infectious patient should have the knowledge and understanding of the disease, methods of transmission and cleaning protocols to be able to care for these patients and protect the others within the hospital/practice.

Genera cleaning

Every day, all areas where any hospitalised patient is housed or treated should be cleaned with an appropriate disinfectant at the correct dilution and for the correct contact time. 90% of microorganisms are present within ‘visible dirt’ and the purpose of routine cleaning is to eliminate this dirt (Infection Control Today, 2010). Neither soap nor detergents have antimicrobial activity; the cleaning process depends essentially on mechanical action (WHO, 2009). Once the infectious patient leaves the practice/hospital or an area within the building, a full deep clean should be carried out. A full deep clean is a thorough clean of the area. It includes all walls, floors and surfaces as well as disassembling all equipment and furniture where possible to allow access to all parts. If possible, it may be prudent to leave the area empty for a period of time after the patient has left. Policies specifying the frequency of cleaning, the cleaning agents used for walls, floors and furniture etc. should be referred to. Cleaning records should be kept stating the suspected, or confirmed, infectious disease, how the area was cleaned, who it was cleaned by and the date and time.

Owner visiting

Discussions regarding the personnel involved in caring for the patient should take place and may include some of the following questions:

The answers are very much dependent on the type of infectious disease the patient has, the veterinary surgeon in charge of them and the practice policy. However, it is important to note realistic client expectations and manage these from the beginning. The owner should be advised to consult their general practitioner for specific advice regarding potential human health implications and it may be advisable that if an owner has an immunosuppressed family member living with them they limit their contact with their pet to prevent transmission.

Procedures and investigations (theatre and treatment rooms)

The cleanliness of the patient for elective procedures is an important factor to consider. Information should be given to the owner on booking the procedure to keep the patient clean. A very muddy dog may need to have a bath before undergoing an elective procedure and owners may need to be advised to take their pet home to do this if necessary.

Areas within the veterinary practice that have a large volume of patients passing through it, especially those areas requiring aseptic conditions, require care to ensure hygiene standards are maintained routinely. Cleaning protocols should be written, with input from all team members within the practice, and then followed. Cleaning can often be pushed to the bottom of the ‘to-do’ list. However, it is very important and time should be factored in each week for a full deep clean to take place as a preventative measure. Cleaning equipment should be specific to each area to prevent cross contamination. It is easy to do this with a colour coded system of buckets, mops, dustpan and brushes and cloths. For example, green for toilets, yellow for theatres, blue for wards and red for isolation areas (although it may be better to use disposable items for the high risk areas).

Cleaning equipment also needs to be cleaned regularly to prevent inanimate objects being a source of infection. Items that are plastic, such as dustpans, buckets and rubber brooms can be disinfected at the standard dilution and for the correct contact time for high risk areas (as per manufacturers' guidelines). Once cleaned and then disinfected the items should be left to dry before being used again (Portner and Johnson, 2010). Items such as mop heads can go into a washing machine at temperatures and times previously described.

Audits of cleaning should be carried out regularly to ensure standards are met and any failings need to be addressed quickly. Methods of assessing environmental cleanliness can be broken down into two types: process evaluation, where the cleaning process is monitored by visual inspection or using a fluorescent gel marker; or outcome evaluation, where cleanliness is evaluated with the use of adenosine triphosphate ATP or microbial cultures (Carling and Bartley, 2010).

Swabbing of areas or equipment may be carried out to identify bacteria, this can be carried out routinely or if the post-operative infection rate causes concern. Human hospitals, and some veterinary hospitals, use an ATP-based sanitation monitoring system. ATP is an enzyme that is present in all living cells, and an ATP monitoring system can detect the amount of organic matter that remains after cleaning an environmental surface, a medical device or a surgical instrument (Infection Control Today, 2010). The results from these swabs can help to provide information to veterinary nurses about how well their cleaning protocols work. It is important to note that positive results will be found even in the cleanest of hospitals as it is not possible to sterilise everything; the aim is to reduce the number of bacteria and eliminate resistant bacteria. The results of swabs need to be taken in context with other factors, such as patient outcome and culture of bacteria in patients. If a resistant bacterial type is found then the area should be closed to new admissions or procedures, a full deep clean should be carried out with an appropriate disinfectant solution at the correct dilution and contact time, before the area is re-swabbed to ensure it has been eradicated.

Theatres should be a restricted access area, and often all personnel entering change clothing and shoes. There is limited evidence to support the changing of clothes although the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Guidelines CG74 do support the wearing of specific freshly laundered theatre wear in all areas where operations are undertaken (NICE Guidelines, 2013). Theatre scrubs should be laundered in a different washing machine to bedding to prevent fluff and hairs attaching themselves to the scrubs and potentially contaminating a surgical site. As with bedding, scrub suits should be laundered at >70°C and be dried in an electric clothes drier as the drying element plays a significant role in reducing bacterial burden (LeTexier, 2001). In addition surgical scrub suits can also be autoclaved, on a drying cycle. This high heat process will have the same effect as drying within an electric clothes drier. In 2010 The Association of Operating Room Nurses (AORN) updated its guidelines and now recommends scrub suits are only laundered within a healthcare accredited facility (Braswell and Spruce, 2012).

Multi-use products

Hygiene of the equipment used for the patients is important. Kennels, cages, food bowls and bedding are obvious points of transmission. Normal dishwashing of food and water bowls is adequate for hospitalised patients with infectious diseases although disposable equipment might be considered in patients in isolation (Garner, 1996). Instruments and other equipment also need to be correctly cleaned. Use of the correct disinfectant, at the correct dilution and for the correct contact time, to clean the items and proper sterilisation of intruments is very important. Once sterilised, instruments and equipment needs to be stored correctly to prevent a break in aseptic conditions such as water damage, tearing of the packet or contamination.

Monitoring within the practice

All members of the veterinary practice are part of a team providing care to the patient and their owners and everyone has their role to play in infection control. Keeping staff informed and trained with regular continuing professional development (CPD) updates helps to remind them all of the potential consequences. Communication between veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses should be two way to make sure each are aware of any post-operative infections — rechecks and nurse clinics are the most likely place for these to be detected. Auditing for post-operative infections include:

These should be tracked and recorded to monitorl any trends. In human medicine a process for feedback of infection rates to clinical care staff were essential components of effective infection control programmes (Collins, 2008)

Conclusion

The above are some ways of ensuring high hygiene standards are maintained. Not all may be applicable to all practices/hospitals, size may limit the option of having a designated isolation ward, but wards can often be adapted to suit.

Evidence an be used to update protocols as more information becomes available. Providing equipment and products and the time required for them to be used correctly plays a major role in preventing the transmission of infectious diseases. Education of all members or practice staff as well as owners is also important. Veterinary nurses can have ongoing training and remain up-to-date with changes to provide guidance and support to others in the practice and owners. Standard operating procedures allow everyone to work to the same guidelines and provide the same standards of care to patients.