There are various ways that patients can become recumbent whether it is following a surgical procedure, trauma, sepsis, or even osteoarthritis in a geriatric patient, the nursing care for these patients will be similar.

Care plans

As every patient is unique the nursing care should also be unique for that patient. It is important to take a holistic approach when prescribing nursing care. While two patients may have the same condition they may cope with the condition differently thus the level of nursing care they require can vary greatly (Jeffery, 2011). It is because of this that a standardised care plan cannot be made for each condition to use as a template as this would not consider all the needs of the patient as an individual. Two patients with similar presenting signs could need different levels of nursing care; for example, two patients being medically managed for spinal disc herniation will require different levels of analgesia, bladder management and physiotherapy depending on the individual's pain threshold, bladder control and its ambulatory status. Roper et al (2002) initially created the care plan model for use in human nursing after research conducted in 1976 which moved nursing care away from a disease-oriented approach to individual care, with a patient orientated approach that is still as relevant today as it was when it was first created (Davis, 2007). The model is based on the patient's 12 activities of daily living (maintaining a safe environment, communicating, breathing, eating and drinking, eliminating, personal grooming, controlling body temperature, mobilising, working and playing, expressing sexuality, sleeping, dying) and considers how dependent/independent the patient is so that nursing interventions can then be implemented accordingly (Jeffery, 2011).

Physiotherapy

Early physiotherapy and turning of patients can help to reduce the risk of cage-rest complications. As recumbent patients are at higher risk of hypostatic pneumonia and decubitus ulcers, it is therefore important to implement appropriate nursing care to prevent these (Bell, 2015). The frequency that patients should be repositioned has been discussed in textbooks and published in articles, however there are limited studies to support the recommendations. The general consensus of the recommendations is to turn the patient every 4 hours although the recommended frequency has varied from 3–6 hours (Bell, 2015). When turning the patient it is important not to turn them directly from one lateral recumbency to the other instead they should rotate between lateral and sternal. When the patient is laying for a period of time in lateral recumbency atelectasis may occur so turning the patient directly from one lateral to the other can cause the patient to desaturate. Additional bedding, sandbags or foam wedges can help aid patient positioning (Figure 1). Other exercises can also be done when the patient is being moved such as supported standing, passive range of motion and also coupage which will help to mobilise any lung secretions (Lumbis, 2007).

Nutritional requirements

The recumbent patient may or may not be able to eat normally, so may require a feeding tube in order to meet their nutritional requirements. Nasogastric, oesophageal or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tubes can be placed depending on the condition of the patient and if enteral nutrition is suitable or parenteral nutrition should be provided. Detailed discussion about nutrition is beyond the scope of this article as the nutritional requirements will vary depending on the reason why the patient is recumbent.

Bedding

Inappropriate or inadequate bedding can quickly lead to development of pressure sores; a padded mattress should be provided followed by suitable bedding material which will draw fluid away from the patient, and this could include disposable incontinence pads under Vetbed. Vetbed can be washed at high temperatures. Recumbent patients can either be incontinent or physically unable to move away if they urinate or defecate in their bed so this needs to be checked frequently. Soiling can lead to urine scalding and may exacerbate hypothermia if the patient is already cold from lying still for long periods of time (Lumbis, 2007). Additional blankets can be used to passively warm patients; warm air blankets, heat pads, hot water bottles or gloves filled with warm water can be used to actively warm patients that are hypothermic. These should all be used with caution and appropriate monitoring as patients are unable to move away from the heat so can easily become hyperthermic and get burned.

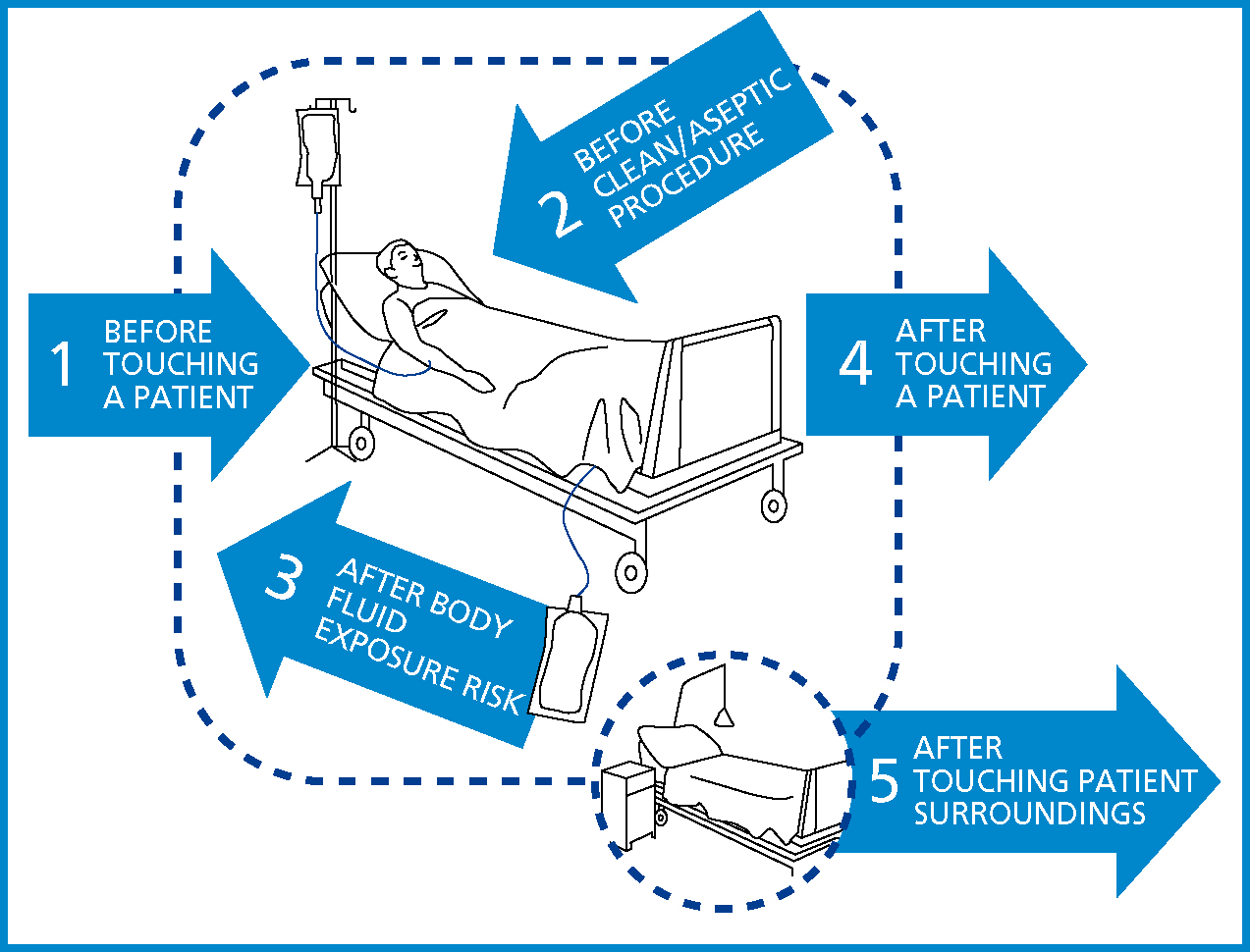

Importance of hand hygiene

When nursing any patient hand hygiene recommendations should be followed and as these recumbent patients often have a variety of medical interventions such as: central lines, peripheral venous catheters, arterial lines and urinary catheters, the use of alcohol hand gels, hand rubs or hand washing should be carried out before and after any patient contact to prevent the spread of nosocomial infections. Gloves should be worn before handling any interventions such as urinary collection bags. Figure 2 shows the five moments that hand hygiene should be carried out as recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO, 2009). Although the diagram refers to human nursing, it is transferable to the veterinary patient.

Indwelling urinary catheters

Placement of an indwelling urinary catheter may be indicated if the patient is urinary incontinent or where urinary retention is expected as with some neurological disorders for example after trauma to the thoracolumbar spinal cord or with detrusor-sphincter reflex dyssynergia. Indwelling urinary catheters must be placed using an aseptic technique to prevent introduction of bacteria which can cause a urinary tract infection (Lumbis, 2007). It is important to ensure no kinking of the urinary catheter or collection system so that unobstructed urine flow is maintained; the collection bag should remain below the level of the bladder but should not come into contact with the floor (Figure 3) as the urinary catheter and associated equipment need to be kept as sterile as possible to prevent a urinary tract infection. The collection bag should be emptied every 4 hours using a clean container for each patient. The volume should be recorded and the urine output calculated (ml/kg/hour) to assess renal perfusion which will help determine if the rate of intravenous fluid therapy needs altering (Oosthuizen, 2011). It is contraindicated to routinely change urinary catheters or collection bags unless the system becomes obstructed, the closed system is compromised or there is infection present as opening the closed system unnecessary can introduce bacteria which can lead to a urinary tract infection and frequently changing the urinary catheter can lead to trauma of the urethra. If infection is present then the urinary catheter may be removed rather than replaced. The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) set a full list of guidelines for the management of urinary catheters for human medicine. Recommendations in human medicine are that the periurethral area does not need to be cleaned with antiseptics while the catheter is in place as routine cleaning of the meatal surface while showering or bathing the patient is appropriate (CDC, 2009); however in veterinary practice recumbent patients may not be routinely bathed, so it may be advisable to clean the periurethral area daily or as required.

Venous access

Depending on the patient's condition, a peripheral venous catheter or a long-stay jugular catheter (central line) may be appropriate. Central lines should be bandaged like other catheters to protect them, the bandage should be changed at least daily or when soiled and the insertion site should be monitored closely for signs of infection and phlebitis, as for peripheral catheters. The advantage of having a central line is that larger volumes of fluid and drugs can be administered at the same time, parenteral nutrition can be given, repeat blood sampling can be performed and central venous pressure can be monitored if needed. Patients presenting with subcutaneous oedema, for example those with hypoproteinaemia or vascular disorders, may prove challenging when trying to gain peripheral venous access and in these cases a central venous line may be necessary. However, a disadvantage of central venous catheters is they usually need to be placed under general anaesthesia and therefore not all candidates will be suitable for this procedure (Moore and Murrell, 2008).

Catheters need to be checked at least once daily by removing the bandage and tape and checking the point of insertion, the bandages should then be checked every 4 hours when flushing catheters (Taylor et al, 2011) and can be checked for soiling during other patient interactions and changed if soiled, damp, or start to become loose (Yagi, 2017). The catheter should be removed or replaced if signs of infection (phlebitis), redness, heat, discharge, pain or a pyrexia of unknown origin occurs. If this happens the catheter should be removed and can be kept in a sterile container, a swab should be taken from the insertion site if there is any discharge in case the veterinary surgeon wishes to send either of these away for culture and susceptibility. The area should be cleaned with a topical antiseptic solution for example a diluted chlorhexidine solution, and the patient's temperature, pulse rate and respiratory rate monitored for any changes to the patient's condition. Further advice should be sought from the veterinary surgeon in charge of the case as depending on the severity they may wish to start antibiotics pending the swab results and also may wish to prescribe other topical treatments.

When checking catheters they should be flushed aseptically with 0.9% saline to ensure patency. A study comparing flushing peripheral catheters with heparinised saline and 0.9% sodium chloride, concluded that heparinised saline did not improve patency when compared with 0.9% sodium chloride therefore using 0.9% sodium chloride to flush catheters without heparin should be sufficient to maintain patency (Ueda et al, 2013). Disconnecting the fluid giving set from the catheter or t-connecter can also be associated with the introduction of bacteria into the catheter when reconnected (Goddard, 2010). Steps can be taken to try and minimise the risk of this by covering the end of the t-connecter with a needle free bung and swap cap when not connected to fluids (Figure 4), placing a needle or syringe bung on the end of the giving set, and cleaning the giving set and catheter ports frequently with a chlorhexidine/alcohol solution (Soothill et al, 2009).

Arterial catheters

Arterial catheters are advantageous when regular arterial blood gas analysis is desired and for continuous arterial blood pressure monitoring. Arterial catheters require more maintenance and monitoring than venous catheters because they are more prone to occluding so need to be flushed hourly.

An aseptic technique should always be followed to reduce the risk of introducing bacteria into the artery. Drugs should not be administered into the arterial catheter so it is important to ensure that it is labelled appropriately (Figure 5) (Haskey, 2016).

Oral care

Unconscious, sedated or anaesthetised patients will require oral care to prevent excessive drying of the oral cavity; if the patient's tongue is left outside of the mouth then it can become excessively dry. Moisten the mouth every 4 hours to prevent this from happening, oral sponges (Figure 6) can be used for this. Gloves should be worn while carrying out any oral care procedures and chlorhexidine-based mouth washes can be used to help reduce bacterial load within the oral cavity (Haskey, 2016).

Ocular care

Patients that have reduced blink reflex or have been prescribed drugs which are known to reduce tear production like opioids should have eye lubrication applied frequently to prevent excessive drying of the eyes which can cause corneal ulcers especially in brachycephalic breeds (Mosing, 2016). The frequency which artificial tears or eye lubrications will need to be applied will depend on which product is being used — with paraffin based ointments, for example Lacri-lube (Allergan Ltd), needing to be used less frequently than artificial tear solutions like Hypromellose eye drops B.P. 0.3% w/v (FDC international Ltd). There are several eye lubricants available so it is important to refer to the data sheet of the product being used in practice; typically lubricants are applied every 2–4 hours.

Other considerations

Grooming the patient can sometimes get over looked as not being a top priority, but this can help to build the human–animal bond and sometimes may encourage an animal to eat (Haskey, 2016).

Sleep is an important part of recovery so when possible medications and procedures should be grouped together especially overnight to give patients the opportunity to sleep. The lights should be dimmed or off and there should be minimal noise to disturb the patients at night (Haskey, 2016).

Conclusion

Nursing the recumbent patient can be challenging at times although it can also be very rewarding when the nurse is able to utilise a variety of nursing skills that improve the patient's comfort and quality of life. With many aspects to consider, developing care plans with a holistic approach helps to ensure gold standard care is provided.