Registered veterinary nurses have a duty to safeguard their patients from risk of injury or harm while they are under their care. In order to fulfil that duty, they must remember the risk associated with feline patients coming into contact with transmissible viruses while visiting the clinic and take action where possible to reduce this risk. Infection control is not a passive process, rather it requires forward planning and implementation of robust measures to protect the patient once they enter the clinic. This article outlines the journey of the feline patient as they travel through the clinic and highlights key points that can be addressed along the route to reduce the chances of all feline patients acquiring a virus.

The entry point — the front door

It is fortunate that in the present day, most cats will travel to the clinic in a secure carrier that reduces the possibility of patients coming directly into contact with each other. Viruses that are spread via open wounds or injection of infected saliva through bites, such as feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) or feline leukaemia virus (FelV), are therefore not easily transmissible in practice and are readily killed in the environment by disinfectant (Möstl et al, 2013). Less fortunately, the client entering the clinic through the front door may have viral contaminant on clothing, shoes and hands, as well as the outside of the cat basket. Viruses such as feline calicivirus (FCV), that are more difficult to kill and can live in the environment for days, may therefore enter the practice via secretions ‘worn’ on clients (Kramer et al, 2006). Hand rubs placed directly inside the front door are useful to encourage instant hand disinfection on entry to the practice and reduce the spread of a variety of infections. Electronic hand rub reminders and sensor-activated doors decrease the risk of contaminated touch points as well as improve compliance, although there is an increased risk of patient escape where sensor-activated doors are used (Ellison et al, 2015). Hand disinfection compliance is thought to be higher with hand rub that is applied and left to dry, compared with that of hand wash that requires water (Addie et al, 2015). Alcohol hand rubs are rapidly effective against a broad spectrum of bacteria and viruses, though are not sporicidal (McDonnell and Russell, 1999). It is worth noting that higher alcohol concentrations in hand rub are proven to have increased efficacy for killing feline viruses, such as FCV (Kampf et al, 2005), with ethanol concentrations above 95% being thought to kill most feline clinically relevant viruses when used appropriately (Kampf, 2018).

The communal area — the waiting room

Feline herpesvirus (FHV) is a common cause of upper respiratory tract disease, though it is less common than FCV. Both viruses are the root cause of feline infectious upper respiratory tract disease (Thiry et al, 2009). Patients infected with these viruses bring highly transmissible secretions into the clinic and are associated with clinical signs such as rhinitis, ocular discharge, sneezing and nasal discharge, that can shed for long periods of weeks, months or even years (Ettinger and Feldman, 2019).

If all cats stay within their baskets in the waiting area and do not come into contact directly with the furnishings or flooring, then they may not encounter other patients' secretions. Those placed directly opposite other cats, however, are at risk of transmitting and receiving infection through secretion of airborne droplets should either cat sneeze.

In 2012 the International Society of Feline Medicine (ISFM), the veterinary division of International Cat Care (ICC), began an accreditation scheme to encourage the improved veterinary care of feline patients. Although the number of feline pets had risen to that of canine pets, the number of cats being treated in practice was lower than that of canines (Endersby, personal communication). This scheme encouraged many feline friendly practices to improve the layout of the clinic and waiting room. Separate sections enabling cats to wait in a different area to dogs are now much more common, with some practices obtaining higher levels of cat ‘friendliness’ by applying barriers between the cats also to reduce the transmission of disease while waiting to be seen (Sparkes and Manley, 2012). Segmentation of the waiting room with ‘sneeze’ barriers plays an important role in the reduction of viruses transmissible by secretion (Figure 1). In a purpose-built practice or ideal world, going one-step further, it may be useful to have a separate suspected viral to a non-viral waiting area. An initial triage by the practice receptionist or nurse to investigate the likelihood of a patient carrying a virus, would allow the appropriate direction to a semi-quarantined section of the waiting room. This could reduce the number of infected patients that encounter non-infected patients; however, some infected patients could then in theory be exposed to second or third viruses and may already be at increased risk if they have lowered immunity. Alternatively, for waiting areas that cannot be segmented, patients could remain in the car if applicable, until the client was called in.

The type of surfaces, chair covers and flooring in the waiting room should be smooth and easy to wipe clean in order to allow appropriate disinfection. Some studies suggest that a sodium hypochlorite solution is the most effective type of chemical for disinfection of feline viruses (Scott, 1980; Eleraky et al, 2002). Contaminated surfaces that contain grains, pores and crevasses may be much more difficult to appropriately clean. Soft furnishings such as chair covers and cushions that cat baskets may sit on, must be removed and washed in hot water regularly at a minimal temperature of 60°C (Dvorak, 2009). Heat is extremely effective at disinfection of a large proportion of viruses, with moist heat being more effective than dry heat (Addie et al, 2015). A steamer is useful on old surfaces or soft furnishings that require thorough cleaning and cannot be removed to machine wash.

The contact point — the consultation room

The consultation room is an area of the practice that requires extra consideration when discussing infection control. This area of the practice, by nature, has the largest amount of feline ‘traffic’ passing through one small focal point, with contact from feline patients repeatedly occurring in the same place, i.e. the examination table.

For larger practices, or those lucky enough to have more than one consultation room, the ISFM encourages a feline only consultation area, separate to a canine patient consulting room. The theory is that this reduces the smell of canine patients in the room thus reducing stress that cats experience with unfamiliar smells and territory (Ellis et al, 2013). The equipment in the room should also be feline specific and tailored for a cat, for example, it may contain a paediatric or feline sized stethoscope, weighing scales and toys. From an infection control perspective, however, this could raise some concerns. Having one small area dedicated to seeing every feline that comes into the clinic does increase the chance of every cat coming into contact with a feline virus, as that is the only place that the feline patients are all seen within the clinic. In a fast paced first opinion practice where there are consultation slots booked in quick succession, the common procedure is that the examination table and scales only are wiped after each patient and then the next patient is seen. The room may not be empty for long enough to allow time for walls and other surfaces to becleaned and disinfected prior to the next patient arriving. The cats are regularly free to jump down from the examination table and wander around the room after the physical examination is complete and the client and veterinary surgeon discuss the treatment.

For infection control to play the much-needed role required here the whole team must be aware of the risks of the transmission of feline viruses that are present. If every person in the practice is conscious of the importance of the role of infection control, then the practice can discuss ways to treat feline patients within the consultation rooms that reduce the risk of patients passing viruses on to each other. If the practice is lucky enough to have a second consultation room that can be used following an examination of a feline patient that is suspected to possibly be shedding a virus, then it allows the contaminated room to have a full deep clean. Practices should allow time for the cleaning and disinfection of all equipment, furniture and walls prior to the next patient entering the room following a consultation with a feline patient that is suspected of shedding a virus. A regular room rotation may reduce the contamination risks associated with the use of a single room, as some virus organisms will become unviable outside of the host without any infection control intervention, such as feline leukaemia virus and feline herpesvirus (Möstl et al, 2013), that are only viable at room temperature for up to 24 hours. A number of clean uniforms to change into should be available for each veterinary surgeon and nurse that are carrying out consultations, if they suspect their uniform has been contaminated during an examination. Personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves and over-suits or aprons play an important role in the protection of the uniform and prevention of the spread of viruses, although personnel should be trained on appropriate use of PPE, as incorrect usage can just as easily increase contamination of surfaces and clothing as no PPE at all (Casanova et al, 2008).

The kennel and treatment areas — the central transmission hub

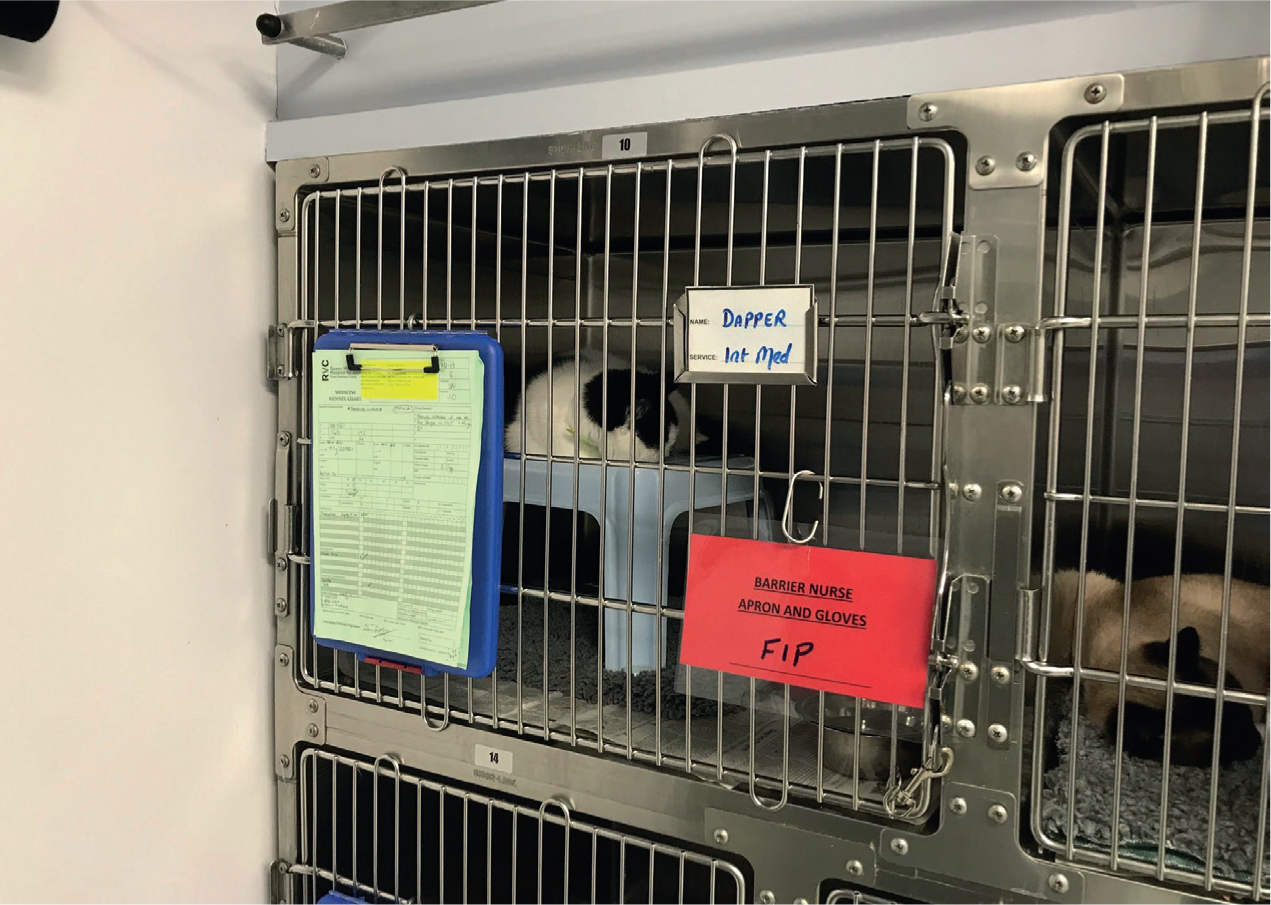

Many practices now have a feline only section of kennels, however many cats carry latent infection that is not detectable, but which resurfaces when the animal becomes stressed or is treated with immunosuppressive medication (Thiry et al, 2009). Good infection control in the kennel area involves careful hygienic husbandry with effective cleaning and disinfectant protocols to prevent the spread of viruses. Viruses such as feline coronavirus are highly contagious and spread through infected faecal matter. The virus is stable in infected litter for prolonged periods of time and once infected, the host may develop feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) through a mutation of the virus, and may continue to shed. Personal protective equipment, such as aprons and gloves, should be used to handle patients that are suspected of disease, and litter trays should be immediately cleaned using detergent following use. This should then be followed by disinfection using by a high quality appropriate veterinary disinfectant. Bedding should be washed at 60°C and food bowls should be soaked in hot water and good quality detergent following use, before being bathed in a disinfectant proven to work against feline viruses. Single use or disposable food bowls for cats are ideal for reducing the risk of transmission of disease; and cat hiding places inside the kennel should be removable as well as easy to clean and disinfect for other patients. Clear signage should be present to prevent personnel inappropriately handling patients that require barrier nursing (Figure 2).

With all surface disinfectants that are applied using a cloth, the basic rule is that organic matter must be removed prior to application. Thorough washing of all surfaces and items must therefore occur to remove dirt. Selecting a dis-infectant that can successfully decontaminate an area with FCV is important as previously discussed; it can remain viable in the environment for days after contamination and is difficult to kill. Knowing the dilution ratio and contact time of the product your practice uses is also extremely important as dilutions and contact times required to kill pathogens can vary using the same product for different individual organisms. Aerosolised disinfectants can prove useful when decontaminating large areas with difficult to reach spaces, that sneeze particles and other secretions may have come into contact with. These should not replace a clinic's standard cleaning practice as discussed, washing a surface prior to disinfection is a key step in the decontamination process and can remove a large proportion of the infectious organism.

On admission to the practice, it is useful to categorise patients into the level of risk that they carry and treat them appropriately. Where possible, offering a kennel space or an isolation area that is dedicated to confirmed infectious patients would be ideal, and would protect those that have no disease. Perspex fronted kennels offer built in sneeze barriers that kennels with bars do not offer. Allocating equipment, such as a thermometer, clipper blade or stethoscope, to use on an infected patient is effective in reducing transmission. Unfortunately, many practices that are not purpose built cannot offer isolation areas suitable for all infection risks and commonly can only offer isolation for one patient at a time. With that, as the feline population increases, the number of veterinary practices being able to offer gold standard options for all of its infectious feline patient caseload reduces.

Conclusion

The feline population is at its highest number for 5 years, with an estimated 140 000 more cats living in the UK now than 5 years ago (Pet Food Manufacturing Association, 2015). The UK is now estimated to be home to 8 million cats (RSPCA, n.d.). That figure having almost doubled in the last 30 years, with there being only 4.6 million in 1985.

Translating the facts we have outlined into practice means that in the future there will be more cats sitting in veterinary kennels, more cats on treatment tables and more cats in veterinary operating theatres. The risk of transmission of disease happening while cats come to visit the practice, therefore, must also be increasing and so too must the importance of the role of infection control. There are many steps that a practice can take to reduce the risk of a feline patient acquiring a virus while journeying through the clinic to allow safe treatment, so…what steps have your clinic taken?

KEY POINTS

- Feline virus infection control should be at the forefront of priorities for all veterinary practices to reduce the risk of patients contracting disease while being treated.

- Analysing the journey of the feline patient as they travel around your clinic can prove useful in addressing all the risks in a methodical and complete approach.

- Good hand hygiene is an effective way of reducing transmission of secretions spread by touch, with hand rub offering more compliance than hand wash.

- Use a veterinary disinfectant that is fit for purpose, with the correct concentration, contact time and temperature being understood and adhered to.

- Raise awareness across the clinic using training, posters and word of mouth to ensure all team members and clients know how to reduce the risks of transmission of feline viruses.