Student veterinary nurses (SVNs) generally receive their practical anaesthesia training during placements, or at their place of employment. Although overall supervision and direction is provided by a veterinary surgeon, the role of ‘instructor’, ‘tutor’ or ‘coach’ during anaesthesia often falls to a registered veterinary nurse (RVN). In contrast with classroom-based lecturers, RVNs in clinical practice generally have minimal to no formal ‘education training’ and approaches to this role can vary. In the same way as literature and resources help develop clinical practice, an understanding of education theories can develop the instructor's skills and identity as a teacher (Butcher and Stoncel, 2012).

Without understanding educational theories and techniques, it is common to rely on one's own personal experiences of education to provide a framework for teaching (Kaufman, 2003). This could include mirroring positive experiences gained from one's own ‘role model’ instructors or avoiding negative experiences such as a ‘sink or swim’ approach and intense questioning. In the experience of the authors, while there is great benefit to learning from role models, all learners are different and therefore what worked for us (as a learner) might not work for our own students. Engaging more with an evidence-based approach to teaching helps to build on experience and allow RVNs to problem-solve their teaching and develop techniques to maximise learning.

Understanding student veterinary nurses as learners: who are they?

Key to helping students learn is to understand them as learners: how they learn and the difficulties they encounter. SVNs are ‘adult learners’ (Knowles 1984a; Knowles et al, 2005), which means they have chosen to study as pre-professionals, and therefore tend to be invested in progressing their knowledge. However, for many this may be the first step in a transition from fully directed school-based learning to professional self-directed learning. Moving from a highly structured approach of being taught, to taking responsibility for learning from one's own experiences, can be overwhelming, and students often struggle to identify what to learn from the plethora of experiences and opportunities available (Lowe and Cook, 2003). Furthermore, they are also learning to work in the clinic, and so in addition to learning the skills and knowledge of nursing practice, they are learning how to be a professional in a veterinary clinic. This involves navigating the social connections of the workplace, taking responsibility for patients, and developing their communication and teamwork skills.

Students enrolled on a degree programme may have already developed some traits of self-directed learning but may still initially struggle in the workplace. Mature students may closer fit the definition of an ‘adult learner’ but will still need support and guidance as they study a novel subject.

Depending on a student's prior experiences of adult education, self-directed learning and the clinical work-place, their approaches to learning will differ and teaching approaches need to vary to reflect this. There are some principles that can be taken into consideration for all adult learners, as initially described by Knowles (1984b), and built on since (Newman and Peile, 2002; Knowles et al, 2005; McGrath 2009). Adults care about the reasons for learning something; they will apply effort when they understand why they need to know something, and their past experiences affect their learning. Internal and external motivators are both driving forces for learning. External motivators can include upcoming assessments, the ‘high stakes’ associated with anaesthesia and others' perceptions of ability, however adult learners progress to be driven more by internal motivators (Knowles, 1984a), such as improving competence and self-efficacy.

This motivational shift creates a preference in adult learners to problem-solve rather than learn straightforward facts; for example, learning to use anaesthetic monitors to identify whether a patient is stable or at-risk is more motivational than memorising wave patterns and normal ranges.

These principles can be applied by RVNs, for example to help students who are struggling to recall earlier-learned facts and apply them in the clinic. Rather than repeating prior taught instruction, the RVN could provide the student with a problem to solve that requires this information and allow them to look up necessary resources to problemsolve the scenario.

SVNs' diversity in prior experience (of learning and of clinic environments) and motivation (internal motivations relating to a passion for anaesthesia, versus interests that lie elsewhere in nursing) mean the most effective teaching strategies will vary between individuals. Grow (1991) described this diversity in students equating it to four stages, between dependant learners through to self-directed learners, and discussed that by adapting the teacher's role to match the student's stage, students can progress through the stages. Table 1 is a modified version of Grow's staged self-directed learning model suggesting how the RVN can support students at different levels when managing anaesthesia cases. Grow (1991) also highlighted the importance of correctly matching student development level to the teaching approach, as a mismatch can be adverse for learning. For example, if a student who is new to clinical/practical anaesthesia (dependant student) is left alone to manage a case with limited support (consultant teacher), they will be overwhelmed, possibly frightened, and likely to make errors with serious consequences. This could lead to avoidance behaviours developing. Conversely, if an experienced student (self-directed student) is continually required to passively watch the RVN manage cases (authoritarian teacher), they may feel frustrated, lose interest and resent the learning process.

Table 1. Applied use of Grow's self-directed learning model in the field of anaesthesia instruction

| Stage | Description of student | Teacher style required | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Dependant — new to anaesthesia, unable to do much independently | Coach; providing authority | Teacher as sole anaesthetist. Explaining what is happening, explaining rationale for action |

| Stage 2 | Interested — willingness to learn, progress and take more responsibility. May not fully understand consequences | Motivator; encouraging progression. Enthusiastic guide | Teacher as primary anaesthetist. Prompting student involvement such as planning anaesthetic cases. Teacher utilises active demonstrations and appropriate questioning |

| Stage 3 | Involved — keen to make decisions based on their skills and knowledge | Facilitator; supports student using their skills, joint decision making | Students as primary anaesthetist and sets own goals. Teacher present as back up. Discussion, questioning |

| Stage 4 | Independent(Self-directed) — can set their own goals and standards, ask for assistance only required | Consultant — setting a challenge, monitor progress | Student primary anaesthetist and sets own goals. Teacher discusses case before and after, suggest broadening focuses e.g. professional skills |

A RVN can only judge and develop their teaching approach if they evaluate and monitor a student's competence and confidence. To do this the RVN must get to know them and so regular individual meetings between SVNs and their instructor are vital and should not be overlooked, rushed, or reduced to a ‘box ticking’ exercise.

This approach of tailoring teaching for the student's benefit is known as ‘student-centred teaching’; it is an understanding that ‘to teach’ is not synonymous with ‘to learn’. The late Sir Ken Robinson described the difference between the task of and the achievement of a verb: ‘You can be engaged in the activity of something, but not really be achieving it… Teaching is a word like that’ (Robinson 2013). He was highlighting that what is easy, or ‘works’ for the teacher does not mean it is necessarily having any effect on the student. In the workplace environment, where the priority is patient welfare and clinical care, a delicate balance has to be found with education. Particularly under stress, it is all too easy to use a teacher-centred approach. RVNs should consider students as individuals and plan their teaching approach to facilitate student learning through suitable activities, leading to their continual development wherever possible (Biggs, 2012). This also means recognising some situations as unsuitable for teaching, such as a particularly challenging anaesthesia case, and so directing students to other suitable learning activities and allowing the RVN to fully concentrate on the patient.

Developing students as self-directed learners

The code of professional conduct for veterinary nurses requires that ‘Veterinary nurses must maintain and develop the knowledge and skills relevant to their professional practice and competence…’ (Royal College Veterinary Surgeons, n.d.). Lifelong development of one's knowledge requires the learner to become self-directed in their learning. Self-directed learning is defined as learning by oneself rather than through another person's actions (Carré et al, 2011), and is thus a vital professional skill, and one that the RVN can develop in their SVNs.

Self-directed learning begins with the learner recognising a gap in their knowledge or understanding, and then defining a learning goal (sometimes referred to as learning objectives) that will help them close this gap. Encouraging students to reflect on their prior experiences helps to identify knowledge and skill gaps, for example by asking about anaesthetics SVNs have seen or participated in or asking them to apply some earlier taught content to an anaesthetic case in the clinic. Goal setting is a skill that must be developed. Often the RVN can help a student's goal become more specific, and by doing so, help them to achieve it. For instance, students may frequently identify that they ‘need to know more about anaesthetic drugs’. This is such an unspecific learning goal, it could be applied to every anaesthetist on the planet! A more specific goal might be ‘explain the adverse and beneficial effects of the selected anaesthetic agents, and what you might see in your anaesthetised patient’. The student could then be encouraged to investigate upcoming cases and make some notes about why they believe the drugs are suitable. If required, the RVN can offer guidance for suitable resources. On conclusion of the anaesthetic cases, whether the student has observed or played a more active role, they can discuss their observations with the RVN or veterinary surgeon, reflect on what they learned, and identify new knowledge and/or skill gaps, which would then lead to the formation of new goals.

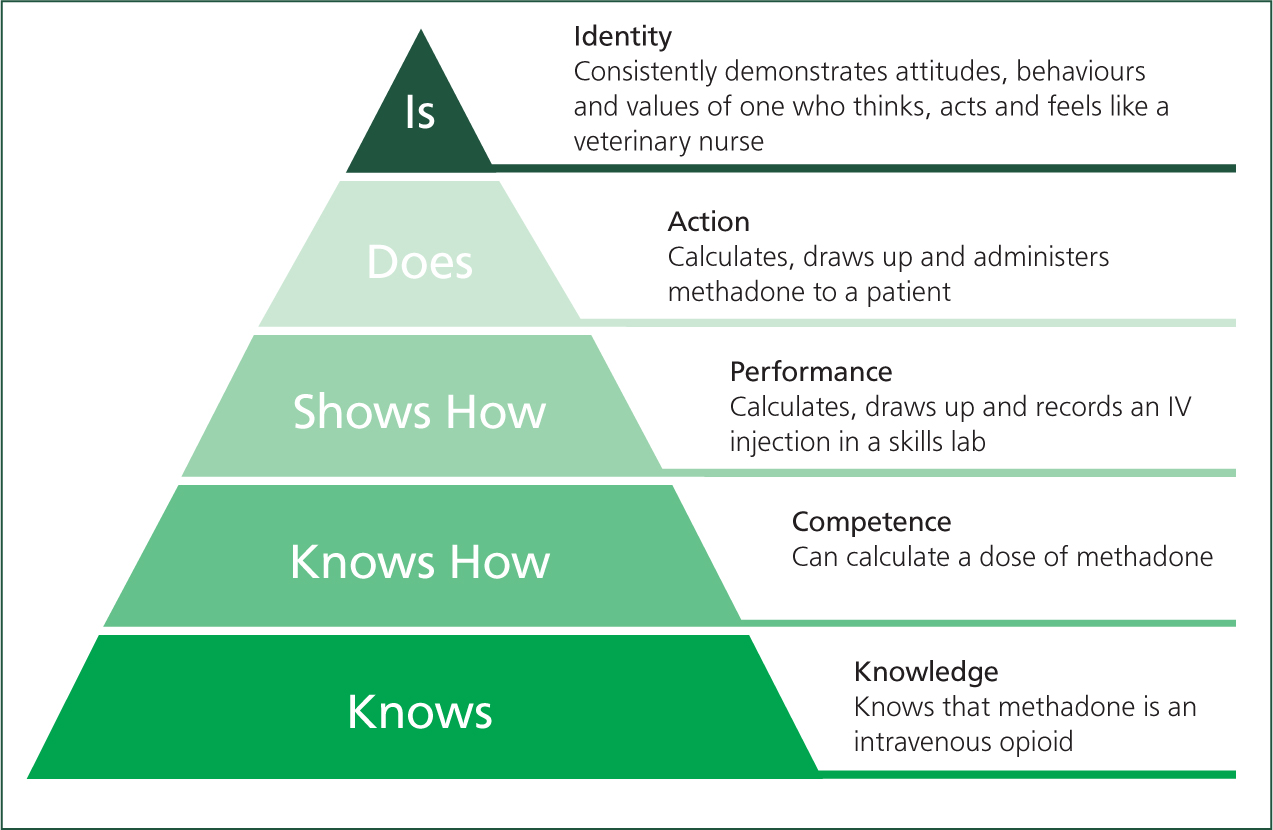

This is a form of ‘deliberate practice’, where attention is paid to improving, not just maintaining skills (Ericsson, 2012). Without goal setting, a student just being involved in anaesthesia cases does not ensure there will be improvement. Cycles of reflection and goal-setting guide the student to advance their learning with each experience (Quinton and Smallbone, 2010). An example would be a student who has assisted with securing an endotracheal tube on many occasions, but never actually placed one. Once this objective is identified, their focus can be shifted during the induction phase of anaesthesia to learn this skill. Miller's pyramid of professional competence highlights the progression in learning goals from ‘knowing’ (about anaesthetics) to ‘knowing how’ (to anaesthetise a patient), and finally to ‘does’ (performs the anaesthetic independently) (Figure 1) (Miller, 1990). This is important for a highly practical subjects, such as veterinary nursing, as all levels should be fulfilled to produce a competent individual (Taylor and Hamdy, 2013). ‘Does’ without knowledge is no better than ‘knowledge’ but unable to do. Miller's pyramid has been more recently updated with the inclusion of an ‘Is’ top tier, representing development and achievement of a professional identity (Cruess et al, 2016). A professional identity can be briefly defined as the individual ‘thinking, feeling and acting like a nurse’ (Godfrey and Young, 2020).

The final stage can include additionally learning to manage the social intricacies of a professional team. Learning objectives focusing on the communication and teamwork required when working alongside veterinary professionals can be formed, such as transferring care to RVN colleagues following anaesthetic recovery or at the end of a shift. Personal goal setting, for example knowing when to seek help with an anaesthetised patient or when to ask for a break (or offer to relieve colleagues), can also be integrated as SVNs develop to higher levels of learning goals. When goals are appropriately developed, the RVN can identify suitable learning opportunities.

This developmental approach to learning is described using Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development Theory, where learning is optimised if a student is encouraged to work on tasks that build on prior experience and are just beyond their independent reach, but which they can achieve with support from a teacher (Vygotsky, 1978; Wass and Golding, 2014). Selecting tasks that excessively over-stretch a student, and not providing them with any support to achieve them is of limited learning value. However, a task, such as helping with a highly complex case, that is beyond the student's current abilities, but they could manage with support, can be ‘scaffolded’ (or supported) by the RVN through adopting techniques such as giving clear instructions and coaching the student through any decision processes. Over time these scaffolds are removed until the student can perform the task independently (Wass and Golding, 2014).

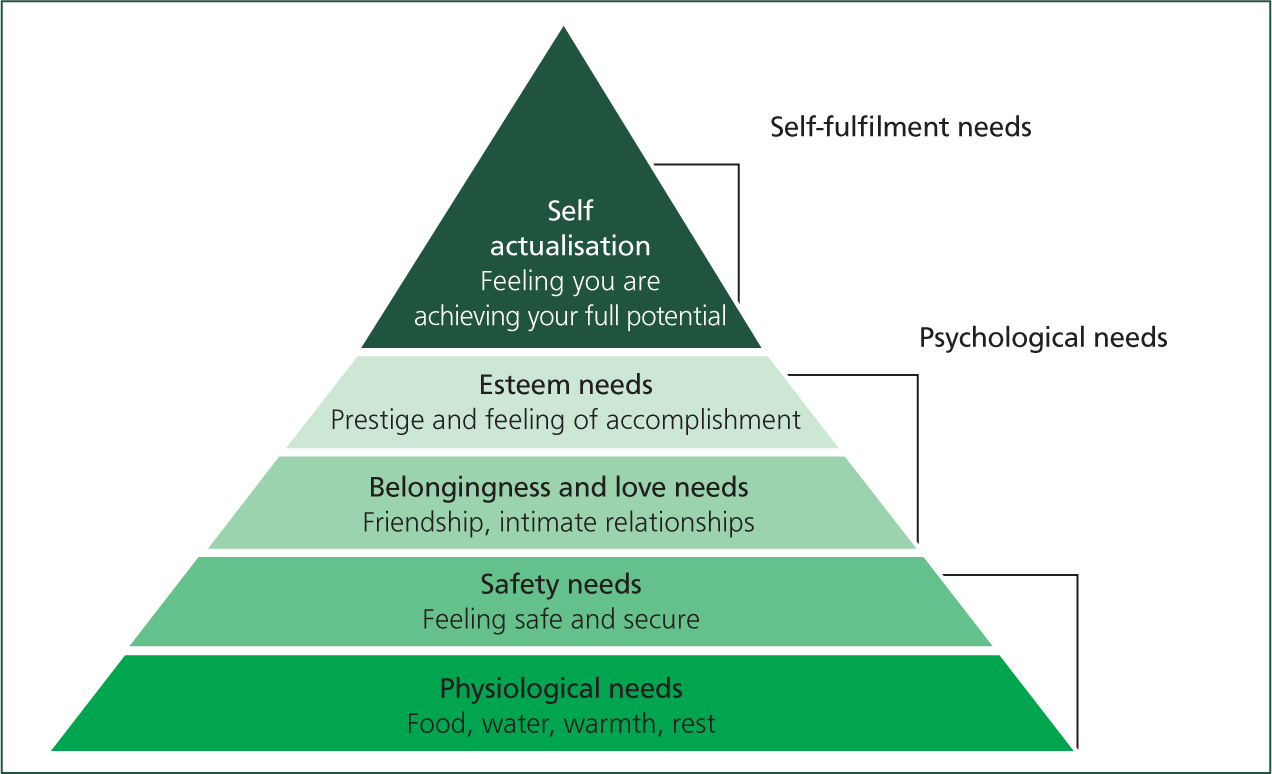

Students will learn in a teaching environment better when they are comfortable and feel accepted by all members of the clinical team (Yardley et al, 2012). Instructors can assist with this by actively ensuring their needs are met or supported. Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs illustrates a pyramid where attainment of each level of need is reliant on reaching the one before (Figure 2) (Maslow, 1943). An adaption of Maslow's pyramid has been described as a framework (rather than pyramid) for supporting medical residents' wellness (Hale et al, 2019). To support meeting basic needs: does the student know when to take their breaks, do they have or know where to get food and drinks, are health and safety concerns well managed for their abilities and experiences? We can promote the meeting of psychological needs by including students within the team and encouraging friendships to form. We can ensure students have meaningful tasks that they feel add to the functions of the workplace and recognise their contributions by giving thanks and praise (Yardley, 2012). The top of Maslow's pyramid can be described as a student feeling that they are reaching their potential and will be interlinked with achievement of other needs. Mentorship of students can help provide support and guidance toward their professional goals (Kerrigan, 2018; Hale et al, 2019).

Conclusion

The passing on of knowledge and experience from RVNs to SVNs is vital to the progression of the veterinary nursing profession. The role of clinical instructor can be challenging, especially in high stakes areas such as anaesthesia. To ensure that SVNs learn in the workplace and in their future careers, while ensuring the welfare of the patient, workplace learning should be as efficient and effective as possible. A basic understanding of educational evidence can equip a RVN with the skills to train SVNs in a student-centred fashion, while promoting the development of self-directed learning skills. Part 2 of this article will use questions commonly asked about SVN workplace training as a framework to demonstrate how the theories from part 1 can be put into practice by the RVN.

KEY POINTS

- Using an evidenced-based approach to educating student veterinary nurses (SVNs) has a positive impact on their learning.

- SVNs are adult learners, but have individual needs because of differing experiences with self-directed learning, adult education, and workplace learning.

- Registered veterinary nurses (RVNs) should match their teaching approach to the student's abilities in different situations, fostering a student-centred approach.

- Self-directed learning skills should be encouraged in SVNs through use of ‘deliberate practice’, and RVNs can assist by helping to set suitable objectives and identifying learning activities.