In veterinary medicine the role of cytology as a diagnostic tool continues to increase. Cytology is a minimally invasive way to obtain a reliable tissue diagnosis (Rick and Cowell, 2008).

The purpose of cutaneous cytology performed in house by a nurse is to identify bacterial, fungal (yeast) or parasitic organisms as well as to identify and describe infiltrating cell types, neoplastic cells, or acantholytic cells. This information allows the veterinarian to assess the significance of such organisms and cell types and their relevance to therapy.

Collection of such samples may involve plucking hair, making tape preparations, preparing smears made from wound or otic swabs, impression smears made from direct contact with the tissue itself and shallow or deep skin scrapings. The techniques and materials needed for these will be outlined in this article. The methods for preparation of these samples for microscopic evaluation will also be covered.

Common dermatological conditions where cytology is routinely used include otitis externa, primary or secondary pyoderma and mange. Common microscopic findings of these will also be covered.

Sample collection and preparation techniques

Equipment needed

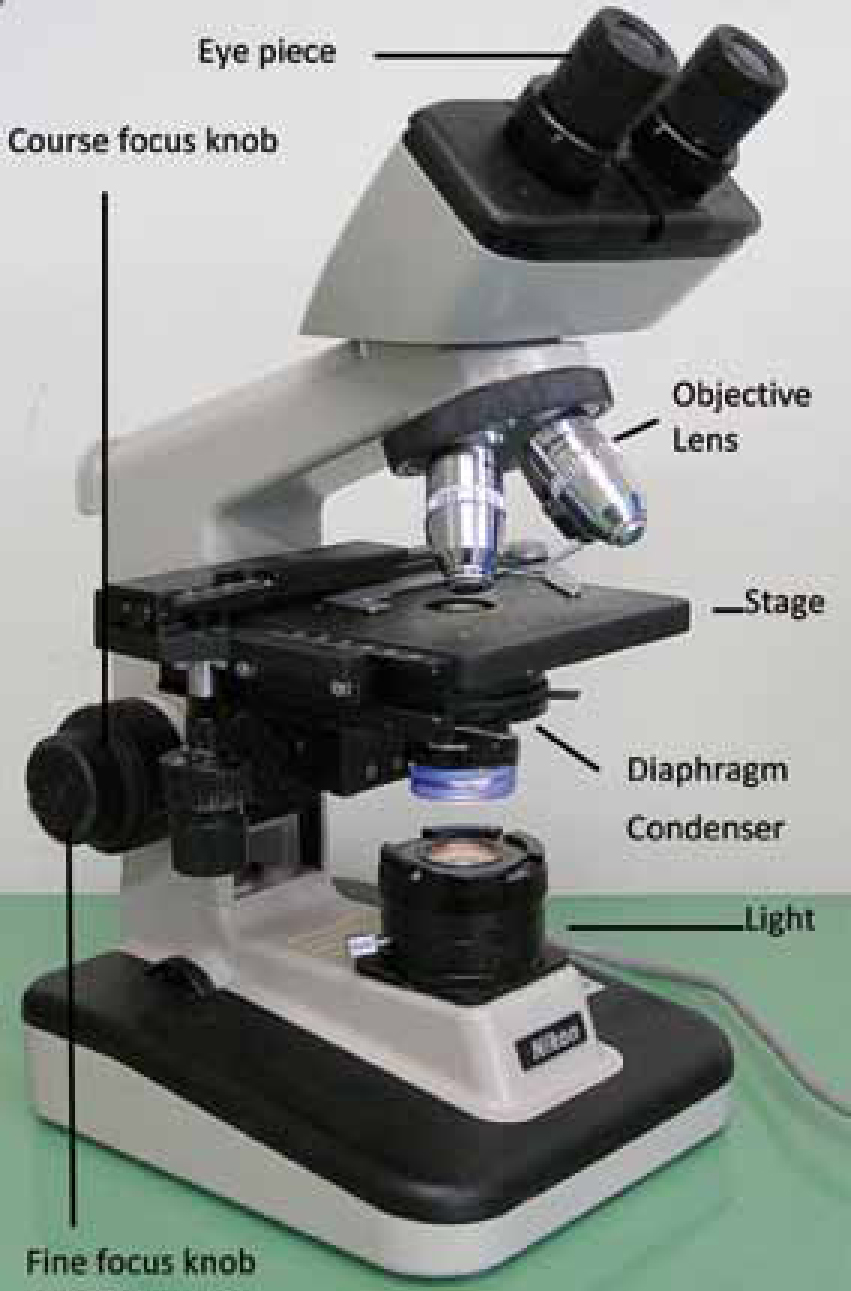

Carrying out cytology in house requires some equipment: a microscope (Figure 1); microscope slides; cover slips; immersion oil; stain; cotton tipped swabs; tape; lighter to heat fix; marker to label slides; paraffin oil; and scalpel blades for scrapes.

Swabs

For moist lesions and wounds a cotton swab should be rolled gently over the lesion or wound. The swab can be moistened with sterile saline to increase the chances of collecting material suitable for examination. The swab should then be gently rolled onto the microscope slide — heat fixing is not necessary but the slide must be dry before staining (Guaguere et al, 2008).

Impression smears

These can be done on moist or oily skin, oozing or discharging lesions. Pustules can be pierced with a small gauge needle — the microscope slide is gently pressed onto the area where the material was produced. Papules can also be pierced. The slide should be allowed to air dry prior to staining.

Otic swabs

After otoscopic examination to evaluate the tympanic membrane, a cotton tipped swab is used to swab down the external ear canal. The collected material is gently rolled on to a clean, dry microscope slide as thinly as possible — heat fixing is not always necessary. Always collect samples from both ears as an animal may appear to have unilateral otitis but have a less apparent infection in the other ear. Label each slide left or right.

Examine the unstained slide under low power (4–10x objective lens) to view mites and identify areas of interest. Stain with Diff-Quick (see section on staining) and view under oil immersion to view bacteria, yeast and cells.

Tapes

Clear acetate tape is used to collect skin samples for cytological evaluation. This method is useful for collecting samples from between toes and skin folds. The tape is pressed onto the affected area and then pulled off and placed on a microscope slide. Stain using Diff-Quick stain (a three step Romanowsky stain) omitting the first alcohol solution stain (the fixative). Blot off the excess stain with a dry paper towel. The tape acts as a cover slip, examine under 100x oil immersion. Tape preps for yeast dermatitis are one of the most useful and easy methods for identifying Malassezia spp. skin infections. Bacteria and inflammatory cells may also be present, but may be hard to identify as there will also be lots of debris on the slide.

Hair plucks

Using forceps hair should be plucked from affected areas and place on a microscope slide. A drop of paraffin oil will help to stick the hair to the slide. This technique can be used to identify Demodex spp. mites.

Skin scrapes

Skin scraping is one of the most common diagnostic procedures used in evaluating animals with dermatologic problems, including mites. Areas of skin with erythema, alopecia, obstructed hair follicles, papules, crusts and altered pigmentation should be scraped. Scrapes should be taken from multiple sites to increase the chance of collecting parasites.

A new dulled scalpel blade is held perpendicular to the skin and scraped with moderate pressure in the direction of hair growth. If the area is covered in hair it may need to be clipped first. Applying mineral oil directly to the skin to be scraped will help to collect the scraped material and dislodge debris. A deep skin scrape is required for Demodex spp. as these mites live deep within the hair follicles. Squeezing the skin helps to express the mites from within the hair follicles, after several scrapes capillaries should become visible and ooze blood and the skin should become red (Linda Medleau, 2006).

The collected sample is then spread onto a microscope slide and examined unstained under the 4 and 10x lens with the condenser lowered to view mites.

Staining

Romanowsky type stains (Diff-Quick, Wright's, Dip-stat) are useful for evaluating skin cytology. Loose material should be heat fixed before staining to ensure loose cells adhere to the slide during the staining process. Stain the slide and allow to dry before viewing.

The basics of focusing the clinic microscope

Focusing the clinic microscope is not difficult:

For more detailed instructions on setting up and using a microscope visit these sites: www.hometrainingtools.com/how-to-use-a-microscope-teaching-tip/a/1120/www.fishdoc.co.uk/microscope/microo3.htm

Microscopic evaluation of organisms

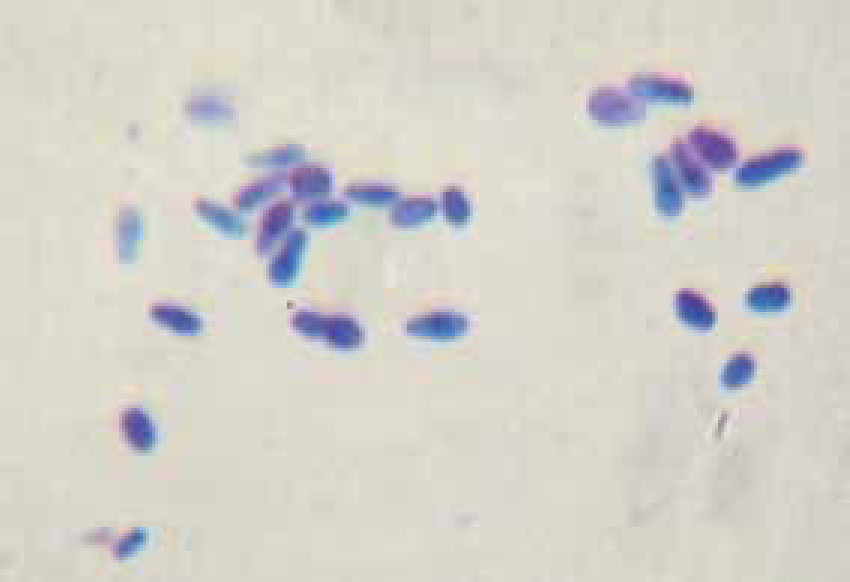

Bacteria and yeast stain dark blue to purple with Diff-Quick. Cells and organisms should be counted in a number of representative fields and then the numbers averaged to get as accurate an impression as possible of what is present. Malassezia spp. yeast look like peanut shaped or foot print shaped organisms (Figure 2).

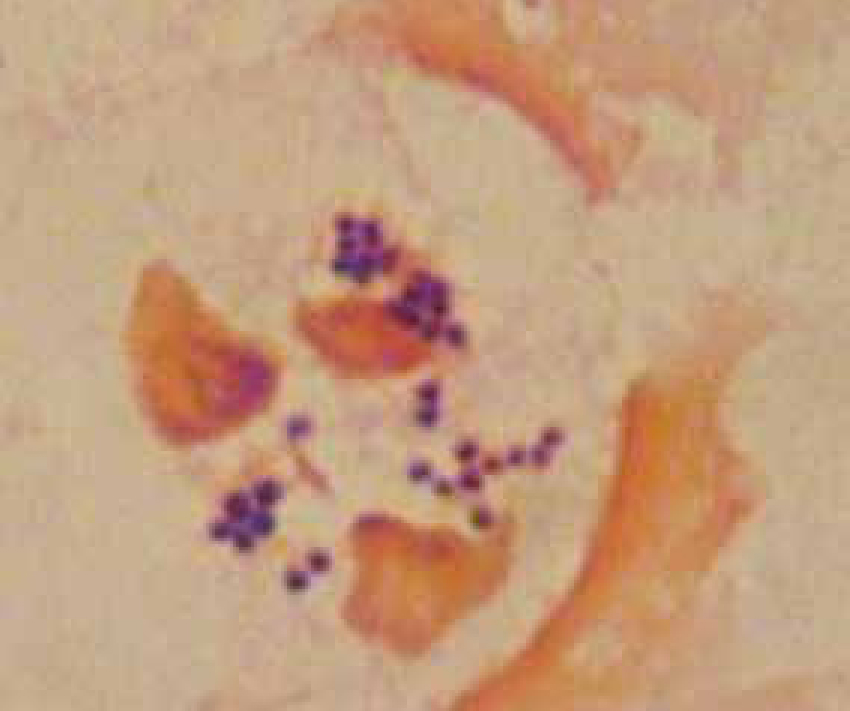

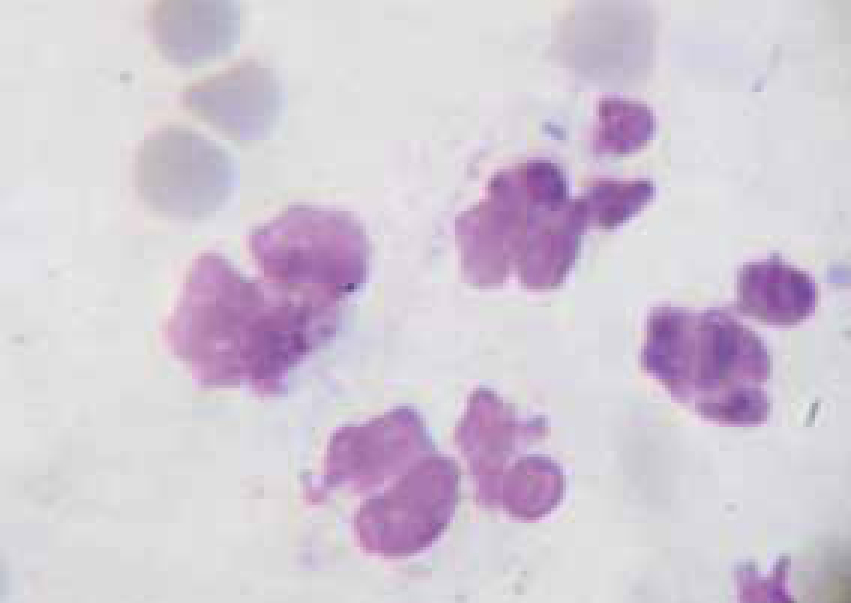

Bacteria should be identified as bacilli (rods) and/or cocci. Bacteria are small prokaryotic (no nucleus) cells. Bacilli (Figure 3) are shaped like rods or cylinders and occur singly or in chains, cocci (Figure 4) are spherical in shape and may be seen singly, in pairs, chains or clusters. Note whether the bacteria is extracellular or within white blood cells (Figure 5 and 6), and whether the organisms are targeting epithelial cells (on the surface of epithelial cells). If present note whether neutrophils are degenerate or non degenerate — degenerate cells show nuclear changes such as pyknosis, karryohexis, kerylolysis, cytoplasmic changes are basophilia asnd vacuolation. Epithelial cells should be classified as nucleate or anucleate.

Conditions where cytology is used for diagnosis

Mangesarcoptes

Sarcoptes spp. (Figure 7) cause a severe pruritus. Patients may present with erythema, crusting and alopecia, secondary infections may be present from excessive scratching. A ‘pinna-pedal’ reflex may also be present, this is when the pinna is scratched and the hind leg involuntarily moves in a scratching motion.

A superficial skin scrape is sufficient for Sarcoptes spp. as these mites do not live deep within the skin. Cheyletiella spp. and Otodectes spp. may also be found.

Demodicosis

Mites of the genus Demodex spp. (Figure 8) are regarded as normal skin inhabitants which reside in the hair follicles and sebaceous glands. Immunocompromised animals may be prone to a proliferation of mites — this is called demodicosis. In cats the mites responsible are Demodex cati and Demodex gatoi. In dogs the mites responsible are Demodex canis, Demodex Inja and Demodex cornei. Microscopically look for cigar shaped mites which will have either a long or short body depending on the species. Eggs may also be seen (Hendrix and Sirois, 2007).

Pyoderma (hot spots)

Pyoderma (bacterial infection of the skin) is considered an opportunistic infection often secondary to an underlying problem such as allergies, immunodeficiencies, hormonal imbalances, seborrhoea, and fungal infections. Bacterial infections cause irritation and pruritus, they are associated with inflammation and malodour is often present. Bacterial dermatoses are rare in the cat despite being common in dogs. The reason for this is the importance of grooming in cats and the small number of bacteria on the coat and skin of the cat (Guaguere and Prelaud, 1999).

There are a number of bacteria that are normal inhabitants of dog and cat skin including: Staphylococcus epidermis, Staphylococcus simulans, Clostridium spp, Corynebacterium spp.

Certain conditions can cause pathogenic bacteria to proliferate. Over 90% of canine skin infections are caused by Staphylococcus intermedius (Guaguere et al, 2008) Other bacteria that are responsible for skin infections are Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus hycius, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis, Escherichia coli, all usually secondary to the growth of S. intermedius.

Bacterial cultures may be suggested when a pyoderma is not responding to what is considered appropriate antibiotic therapy. Increased resistance of bacteria to antibiotics is on the rise in veterinary medicine as well as in human medicine.

Bacterial culture swabs must be collected aseptically and care should be taken not to touch the sterile swab to anything other than the area being sampled. Swabs can be taken directly from a moist or open lesion, from pustules that have not yet broken open using a sterile needle and swabbing the purulent material. The swab should be placed carefully into the transport medium.

Inflammation

Inflammation is the normal physiologic response to invasion by micro-organisms or tissue damage. Cytology from inflammatory sites is characterized by the presence of white blood cells, especially neutrophils and macrophages (Figure 9), lymphocytes and eosi nophils may also be present occasionally. Based on the numbers of various cell types present inflammation can be categorized as (Hendrix and Sargi, 2007):

Malassezia pachydermatitis

Malassezia spp. (Figure 2) dermatitis is a yeast infection of the skin. It is relatively frequent in dogs and very pruritic. Clinical signs include an odour of rancid grease, erythema, greasy seborrhoea, crusts, diffuse alopecia, papules, erythematous maculae, hyperpigmentation and lichenification when chronic. (Pierre Jasmin, 2005). Malassezia spp. is a common inhabitant of skin, ears and anal glands — an average of 3 yeasts per microscopic field in an animal with clinical signs is considered diagnostic of Malassezia spp. dermatitis (Pierre Jasmin, 2005). Yeast infections are usually secondary to conditions that cause an increase in skin oils, for example, endocrine disorders (especially hypothyroidism), allergies, seborrhoeic conditions and immune deficiencies. Overuse of steroids may be a contributing cause, ectoparasites, especially Demodex spp, may cause secondary yeast infections. Breeds of dogs predisposed to Malassezia spp. infections include West Highland White Terriers, Cocker Spaniels, Basset Hounds, and Poodles.

Otitis externa

Otitis externa is an acute or chronic inflammatory disease of the external ear canal. Otic pruritus and pain are common symptoms of otitis externa. Causes are described in Table 1. Patients may present with a head tilt, head rubbing, ear scratching, aural haematomas and head shaking. Frequently dogs with ear disease have concurrent skin disease that also requires identification and treatment. The generalized skin disease pattern can help with the differential diagnosis for the ear disease (Bloom, 2009). It has been reported that 50–83% of atopic dogs have otitis externa (Rick and Cowell, 2008).

|

|

Otic cytology

Normal ear swab specimens (Figure 10) have negligible evidence of inflammation and few micro-organisms. Cornified squamous epithelial cells are present. Common abnormal findings are yeasts or bacteria, with or without inflammation. Controversy exists among specialists regarding whether the presence of Malassezia spp. in small numbers is significant. Some believe that any organisms found are grounds for treatment, whereas others claim that low numbers may be found in normal ears (Hendrix and Sirois, 2007).

Common abnormal findings

Ear mites

Ear mites are a primary cause of otitis externa and especially common in cats. It has been reported that Otodectes cynotis (Figure 11) accounts for 50% of feline cases of otitis externa and 5–10% of canine cases. (Rick and Cowell, 2008). Typically a dry black aural exudate is seen. Secondary bacterial and/or yeast infection often coexist, which can result in a moist aural discharge.

Bacteria

The ear canals of clinically normal dogs contain occasional or no bacteria. When normal ear canal conditions are altered, such as in hot humid conditions or after swimming making the ear moist, allergies, parasites, excessive hair plucking, foreign bodies and skin disease, these bacteria can colonize the ear canal. Cytological evaluation of ear canal exudate in animals with bacterial otitis often reveals large numbers of bacteria. Identifying cocci or rods can help in initial selection of antibiotics since most cocci are gram positive and most rods are gram negative. Both rods and cocci may also be found (Figure 12). There is a high incidence of antimicrobial resistance associated with otitis externa (Rick and Cowell, 2008). Culture and sensitivity testing is indicated when routine therapy is ineffective.

Yeast

In dogs and cats Malassezia pachydermatis is the most common yeast associated with otitis externa. When predisposing factors provide a favourable environment an overgrowth occurs. A dark brown, sweet smelling exudate occurs in pure Malassezia infections. Concurrent bacterial and Malassezia infections commonly occur.

Other findings on cytology

Simonsiella (Figure 13) are a non-pathogenic bacterial inhabitant of the mouth and indicate an animal has been licking when found on cutaneous cytology. Simonsiella are large rod shaped striated organisms, which appear as a single large bacterium but are actually several rods side by side giving them the striated appearance.

Hyperplasia

Hyperplasia is an increase in the number of cells of an organ or tissue found in response to injury, inflammation or excessive stimulation. Hyperplastic cells look more immature than normal tissue cells, they are often larger, and do not stain as uniformly in the cytoplasm as mature cells. They often have prominent nucleoli, and larger amounts of cytoplasm, the nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio usually has little variation. Inflammatory cells may also be present.

Neoplasia

Neoplasia is the term used to describe any growth such as a tumour, which may be benign or malignant. Neoplastic cells have a variation of nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio, variation of cell size and variation in nuclear size. Nucleoli are present within the nucleus and some nuclei may show signs of dividing, a variable amount of cytoplasm in each cell with vacuoles may also be seen.

Conclusion

Equipment for performing otic and skin cytology is readily available and inexpensive. To become proficient at reading samples care must be taken, debris and organisms can easily be confused. To ensure slides are accurately read look at a large number of slides and compare results with trained personnel. Have at least one reference book at hand. Making an extra slide to view in house and comparing them with lab results is a great way to get better at identifying cells and organisms. With practice veterinary nurses can become adept at a number of microscopic techniques including skin and otic cytology. Once the basics of cytology are mastered it is possible to expand into other areas where cytology is used for diagnosis such as fine needle aspirations, wound swabs, biopsies, fluids, blood smears, and urinary sediment.