Often when a client's pet cat is diagnosed with feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) it can mean a complete lifestyle change for both pet and owner. It is the role of the veterinary professional to help the owner and their feline companion make the transition and to give their cat the best quality of life they can for as long as possible. This article provides some insight into what the disease is, how it works and what veterinary professionals, can do to help their FIV-positive patients and their owners.

What is FIV

FIV is a retrovirus that causes immunodeficiency in cats. It is in the same subfamily (lentiviruses) as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Irwin, 2011). It was initially named the Feline T-Lymphotropic Lentivirus (FTLV) because it belonged to the lentivirus subfamily (Hopper et al. 1994). FIV can also be known as feline immunodeficiency syndrome, feline acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and FIV infection. It was discovered in 1986 by the University of California (Davis) Veterinary School when they investigated an outbreak of disease in a previously healthy colony of rescue cats (Hopper et al. 1994).

After the initial infection (generally through a bite wound) (Irwin, 2011) the virus moves to regional lymph nodes and viral replication occurs where the virus spreads throughout the lymph system.

A survey of exotic cats (Barr, 1989) showed evidence of FIV infection in several zoo populations, including snow leopards, lions, tigers and jaguars, and also in free-roaming populations of Florida panthers and bobcats (Hopper et al. 1994).

FIV facts

Incidence

Serological surveys have been conducted in several countries to determine the prevalence of FIV infection in various cat populations. These findings are summarised in Table 1.

| Country | Number of cats tested | FIV positive (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK | 1007 (healthy) | 6 | Hosie et al (1989) |

| 1204 (sick) | 19 | ||

| UK | 224 (healthy) | 6 | Hopper et al (1991) |

| 1450 (sick) | 17 | ||

| The Netherlands | 123 (healthy) | 1 | Lutz et al (1988) |

| 98 (sick) | 3 | ||

| Switzerland | 178 (healthy) | 3 | Lutz et al (1988) |

| 775 (sick) | 4 | ||

| USA | 361 (healthy) | 1 | Shelton et al (1989) |

| 226 (sick) | 10 | ||

| Japan | 1584 (healthy) | 12 | Ishida et al (1989) |

| 1739 (sick) | 44 | ||

| Australia | 72 (healthy) | 29 | Robertson et al (1990) |

| 211 (sick) | 28 |

Most of these surveys show that the prevalence of FIV infection is much greater amongst sick cats, i.e. those with clinical problems (as a result of secondary infections), than healthy cats. However in The Netherlands, Switzerland and Australia there was only minimal difference between percentages of sick and healthy cats with FIV, which could be due to a variation in strains of FIV in these countries that are possibly less pathogenic than those found elsewhere (Hopper et al. 1994). Alternatively these findings may alter if a greater number of cats are studied.

In addition, the frequency with which a cat will encounter other cats outside its own household should be considered. In a majority of cases the highest prevalence of infection occurs in those cats which most often meet and have contact with other cats (Hopper et al. 1994). Table 2 highlights the strong association of FIV infection with free access to the outdoor environment as opposed to show cats that are often kept partially or totally confined indoors.

| Population | Number tested | Number FIV positive (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feral cats | 90 | 24 (27%) | Bennett et al (1989) |

| 70 | 29 (38%) | Hopper, unpublished | |

| Farm cats | 50 | 12 (24%) | Hopper, unpublished |

| Pedigree show cats | 77 | 0 | Hopper, unpublished |

Diagnosis

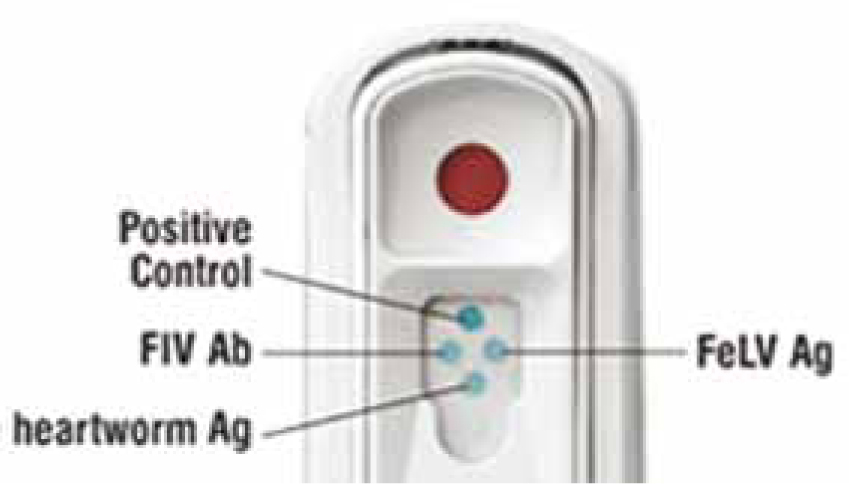

FIV can be detected through a variety of laboratory tests, one of the most commonly used today is the SNAP FIV/FeLV combo test (Idexx Laboratories) (Figure 1). This combo snap test uses enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technology and can be used with either serum, plasma or anticoagulated whole blood samples. The benefit of the snap test is that it can be done in-house with results in as little as 10 minutes. Veterinary diagnostic laboratory testing can also provide alternative means of detecting the presence of the FIV antibody such as more complex ELISA testing with serum and western blotting (immunoblotting). The western blot can be used with either serum or plasma and is widely recommended as a confirmatory test for previously positive FIV results (Barr, 2000). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing can also be used as a confirmatory diagnostic method to achieve a definitive diagnosis of FIV (Taylor, 2006). The standard recommendation for FIV testing is the Idexx SNAP FIV/FeLV combo test with confirmation provided by western blot (Taylor, 2006).

Diagnosis of FIV is generally reliable however false negative and false positive results can occur. If there is any doubt or uncertainty of the results; a repeat test should be carried out after a definitive period of time of approximately 2 months (Barr, 2000) with the exception of kittens under 6 months old. An alternative method of testing should be used if possible (Hopper et al. 1994) such as laboratory ELISA testing rather than the Idexx Snap FeLV/FIV combo test with either the western blot or PCR test for confirmation of results.

False positive and false negative test results can occur in some of the following circumstances:

Clinical signs

Following the primary phase of infection most cats are thought to undergo a prolonged period when they are free of clinical signs attributed to FIV infection. The asymptomatic phase may last for years (Irwin, 2011). Nevertheless, experimentally infected cats have been shown to develop a progressive deterioration in immune function, and probably in the majority of naturally infected cats this eventually leads to the development of clinical signs (Table 3) (Hopper et al. 1994).

| Common signs | Other signs |

|---|---|

| Depression | Vomiting |

| Weight loss | Recurrent cystitis |

| Pyrexia | Neurological disorders |

| Anorexia | Behavioural disorders |

| Chronic diarrhea | Neoplasia |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | Otitis externa |

| Gingivitis and/or stomatitis | Renal disease/failure |

| Chronic dermatosis | Chronic abscessation |

| Chronic ocular signs | Reproductive failure/ abortion |

| Lymphadenopathy | Seizures |

| Fever | Paresis |

The average time between a cat becoming infected and obvious clinical signs can be as much as 6 years and sometimes as early as 2 years after infection; however this varies greatly on a case by case basis (Barr, 2000). Non-specific signs of weight loss, lethargy and depression may be associated with the terminal stage of the disease (Taylor, 2006). However further investigation may be required as these signs may suggest the onset of another disease due to chronic immune suppression.

Case study

‘Kit Kat’ was an abandoned cat and at the time of arrival in the clinic (approximately 2 months after being found by the author in March 2005), her age was estimated at around 2 years (Figure 2). She appeared healthy and active and had been spayed previously. On the 17th April 2005 she was given her first vaccine that was to cover her against feline rhinotracheitis, calicivirus and panleukopenia; these are all modified live viruses.

On the 20th of May 2005 Kit Kat had a sudden onset of lameness in her left hind leg. Due to the pain she was hard to examine so was kept in clinic and sedated with medetomidine hydrochloride (Domitor 1 mg/ ml, Pfizer Animal Health NZ Ltd). No abscess, swelling or instability was evident so she was tentatively diagnosed and treated for cellulitis with antibiotics (amoxycillin (Clavulox 50 mg tablets, Pfizer Animal Health NZ Ltd)) and analgesia (meloxicam (Metacam 0.5 mg/ml oral, Boehringer Ingelheim NZ Ltd)). Kit Kat had no other clinical signs and appeared in good health apart from her lameness. The lameness improved, but did not get completely better.

On the 22nd of June 2005 Kit Kat presented with sudden onset of severe lameness, but this time in the right hind leg. Again no wounds could be found on examination and there was no obvious indication as to what was causing the problem. This time however Kit Kat also had a fever and lack of muscle mobility in her lower back and left hind leg. The veterinary surgeon suspected toxoplasmosis infection however he was not completely satisfied with this diagnosis and requested a further revisit if problems persisted. Kit Kat remained on amoxycillin and meloxicam.

On the 5th July 2005 Kit Kat presented with no movement in her lower back or either hind legs. She refused to eat and would not allow her hind limbs to be examined, showing signs of pain. Kit Kat was sedated for a physical examination and for pelvic radiographs as the superseding veterinarian believed she had been hit by a car and had a fractured pelvis and that these clinical signs were not related to previous visits as Kit Kat had been showing improvement with the continued use of amoxycillin and meloxicam. Radiographs were clear with no obvious problems or fractures and the physical examination was unable to find anything either.

The suspected problem was tentatively thought to be polyarthritis syndrome. Diagnostic testing revealed an established inflammation process however the veterinarian was cautious in this diagnosis and Kit Kat was discharged with broad spectrum antibiotics (amoxycillin (Clavulox 50 mg tablets, Pfizer Animal Health NZ Ltd)) to treat any potential bacterial infection that was responsible for the clinical signs.

On 12th July 2005 Kit Kat returned due to decreased mobility and deterioration of general health. A joint tap revealed no evidence of bacteria but evidence that was consistent with degenerative joint disease such as chronic progressive polyarthritis associated with a viral infection or chronic immune suppression. Based on Kit Kat's history the veterinarian ordered a laboratory ELISA test for possible FIV infection which showed positive test results for FIV. A western blot test was then scheduled to confirm the status. Kit Kat was prescribed and discharged with analgesia (meloxicam (Metacam 0.5 mg/ml oral suspension for cats, Boehringer Ingelheim NZ Ltd)) to help what appeared to be pain from muscle degeneration due to the disease.

By the 15th August 2005 the pain relief had been effective and Kit Kat was looking well. A physical examination showed no abnormalities detected. A plan was then put in place to see Kit Kat on a 6 monthly basis to monitor her condition and check for any secondary infections for the rest of her life. Part of the plan was that Kit Kat would remain an indoor cat with regular de-worming and de-fleaing and on the Hills Indoor Cat diet to meets all of her nutritional requirements. No further vaccinations were recommended and it was made clear that if she was to be in a cattery environment she must be isolated from other cats and in a separate air space to minimise the risk of contracting any feline respiratory viruses from asymptomatic carriers. Based on her history she was conservatively expected to have approximately 5 to 8 months to live from the time of diagnosis. She currently lives with the author, and is approximately 10 years old.

Once diagnosed and put onto a treatment plan Kit Kat managed well with her FIV status and she adapted well from being an outdoor cat to one restricted indoors. FIV was not initially tested for as at the time it was not commonly a routine test in New Zealand due to cost factors and only limited practices offering the Idexx Snap FeLV/FIV combo test. She does have muscle stiffness occasionally but whether this is simply due to her age or pain from the muscles due to the disease is unknown.

Control/treatment

The most effective method of control is to keep cats indoors to protect them from exposure to secondary pathogens and prevent the spread of FIV to other cats. FIV positive cats should be monitored regularly for evidence of secondary infectious diseases, neoplasia, and progression of illness (Taylor, 2006). Furthermore the treatment of secondary and opportunistic infections is important and can be assisted by supportive therapy such as fluid therapy, antibiotics and nutritional supplements (e.g. vitamins C and B) as required (Barr, 2000).

Vaccination for other infectious diseases is recommended only for those cats at a high risk of developing an infectious disease (those in open multi-cat households). When vaccinating an FIV positive cat against other infectious diseases, only inactivated vaccines should be used so as not to cause further immune suppression through the development of antibodies (Taylor, 2006). There are currently no specific anti-viral agents effective against FIV that can be recommended for use in cats (Hopper et al. 1994).

Ideally for best practice FIV positive cats in clinic should wait in a spare, clean, consult room, and be housed separately and away from other cats to lower the risk of contracting respiratory viruses. They should be given additional support as needed during their procedure on a case by case basis such as fluid therapy and prophylactic antibiotics.

Client education

The importance of keeping FIV-positive cats indoors should be discussed with clients as it prevents them from roaming freely, limiting their exposure to secondary pathogens and helping to prevent the further spread of FIV. The importance of neutering cats should be emphasised to aid in restricting their roaming and potential aggression. Associated conditions can include secondary bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic disease, lymphoid tumors and immune-mediated disease.

The infection is slowly progressive and healthy antibody-positive cats may remain healthy for years.

FIV vaccines are still in development and current FIV vaccines are not uniformly active against all strains of the virus (Barr, 2000). There is currently no known zoonotic potential between humans and other animals and FIV positive cats. However there is a higher risk of secondary pathogen transmission to immune-compromised humans (e.g. toxoplasma gondii). Within the first 2 years following diagnosis or 4 to 6 years after the estimated time of infection, about 20% of cats die, but more than 50% remain asymptomatic (Barr, 2000). Clients need to be aware that cats with clinical signs will have recurrent or chronic health problems that will require medical attention. The overall prognosis for cats infected with FIV is guarded. Some cats show improvement following treatment for secondary and opportunistic infections that may be maintained for months or even years.

Conclusion

While a diagnosis of FIV does usually mean a lifestyle change for the cat the disease can be well managed. By working with owners and educating them about controlling this disease, their feline companion can often go on to live a relatively normal life. It is also important to remember the possible issues surrounding false positive and false negative diagnostic results. By refining when tests are undertaken for this disease false negative or poitive results can potentially be eliminated, and clients provided with the most accurate information regarding the future of their pets. Educating clients and owners on the ways to stop the spread of FIV, and the importance of stopping its spread, may result in a decline in the numbers of FIV-infected domesticated cats.