For veterinary professionals in practice, the presence of linguistic conventions helps to maintain a sense of ‘knowingness’ about the working world. Veterinary nurses know a TPR from a CPR and a CRT from an RTA. However, do they ever stop to think about the wider terms that are used to relate to animal patients or the use of negative animal-related metaphors in everyday language? Negative animal expressions such as ‘there's no use fogging a dead horse’ and ‘as sly as a fox’ together with words such as ‘beast’ and ‘brute’ are both ubiquitous and popularly employed. However, as concern about the status and welfare of animals in society grows, veterinary nurses may wish to reconsider the familiar as it applies to animal nomenclature. In 2011, the editors of a new publication The Journal of Animal Ethics suggested that language terms popularly used to describe animals, for example ‘pet’ or ‘vermin’, are historically derived from a state of human condescension and convenience. The implication is that such terms are not necessarily consciously derogatory but nevertheless harmful in the way that human beings conceptualize and consequently relate to non-human animals (Cohn and Linzey, 2011). Although an academic journal, the periodical's thought-provoking position was markedly misrepresented by the popular international media. Sensationalist headlines such as ‘Don't Call Your Furry Friend ‘Pet’ It Could Drive Them Wild’ (Daily Star Online, 29th April 2011) and ‘Animal Academics: Using The Word ‘Pet’ Insults Your Pet, Er, Companion’ (Time Magazine Online 29th April 2011) added an irrelevant distraction to the debate by suggesting that animals themselves would be offended by the use of such terminology. Unfortunately, such stories missed a very valid point. The article did not suggest that animals find such language degrading. Instead, it proposed that because language can be both descriptive and prescriptive in its application, the modern use of terms previously associated with the denigration of animals can be detrimental to the way they are perceived. To understand why this may be the case, it is important to take a look back through history and relate the historical development of attitudes towards animals to the way they are currently spoken about.

The historical animal

According to Taylor (1986), there are three major philosophical traditions in the ‘West’ which have biased human beings over non-human animals: classical Greek thought; Biblical doctrine; and the philosophy of Rene Descartes. Beginning with Ancient Greece, Aristotle suggested that the natural world existed in a hierarchy of increasing biological and mental complexity from ‘lower’ animals such as insects through to man, the lone possessor of rationality and a ‘soul’ (Newmyer, 2007). This theme continued in Roman society where this universal ‘natural’ order was upheld by the use of animals in ways that publically perpetuated the superiority of human beings, particularly through the mass slaughter of animals in the Gladiator arenas (Newmyer, 2006). Similarly, Biblical notions of ‘dominion’ over animals gave rise to an early medieval idea that mirrored the hierarchical human–animal relationship of ancient Western civilization. These religious sentiments were crucial in fuelling later anxieties in early modern England concerning transgressions of boundaries between humans and animals (Thomas, 1983). Later, in the 17th century in pre-enlightenment Europe, the French philosopher Rene Descartes suggested that all bodies work like machines but minds are separate from the body and uniquely human, an idea that came to be known as Cartesian Dualism (Descartes and Clarke, 2003).

During the following century, significant voices started to speak up in defence of animals, most notably the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham. Bentham's work helped to pave the way for the introduction of rudimentary English animal welfare legislation in the 19th century (Serpell, 1986). Bentham suggested that animals are worthy of moral consideration, not because they can talk or reason, but because they are capable of suffering (Bentham, 1789). However, many negative animal-related metaphors still originate from this time. Although sentimental feelings towards animals began to to surface in the UK during the early Victorian period, the reality of animal treatment was still one of brutality. Public beatings of draught and food animals were commonplace and the abuse of animals in both domestic life and ‘sporting’ activities, such as cock and dog fighting, aided the development of negative animal metaphors in the English language (Kean, 1998; Dunayer, 2001).

Pet — affection and domination

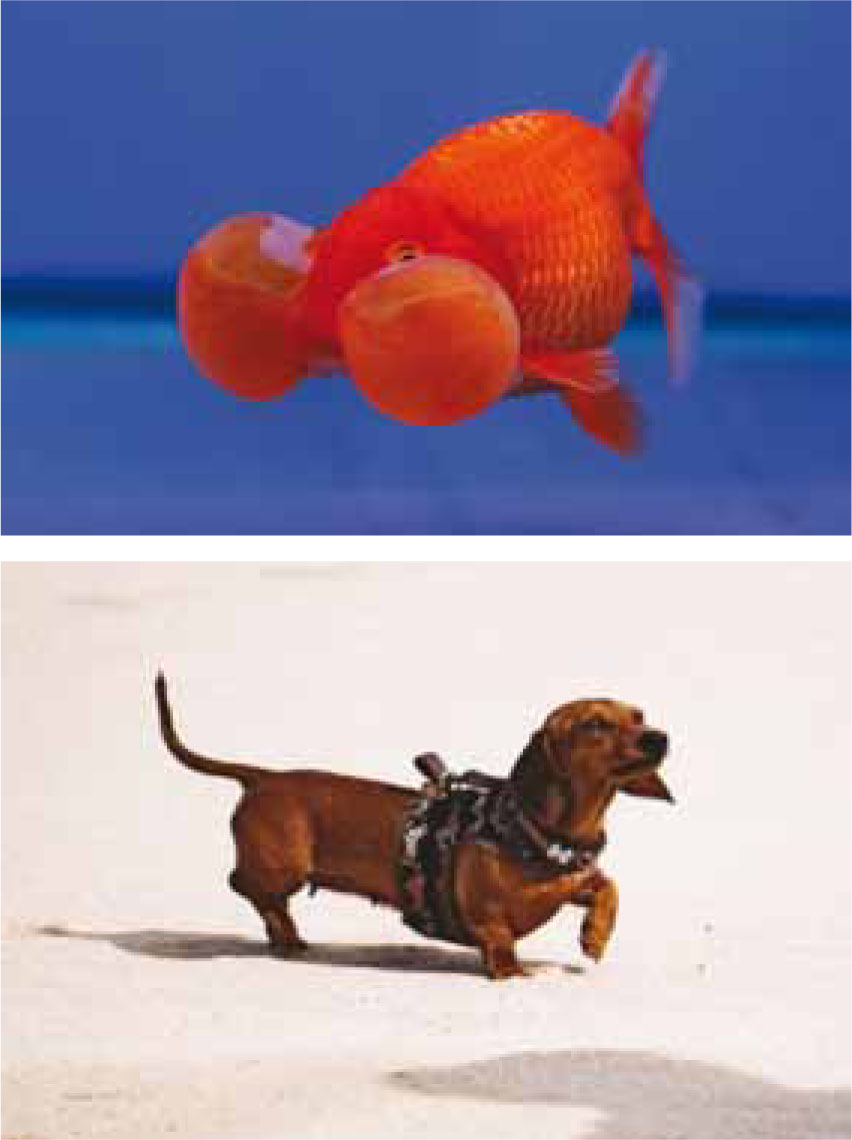

According to Chamber's Dictionary of Etymology, the word pet originates in the early 16th century. Adopted from Northern English and Scottish dialectical usage, it was more than likely derived from the Middle English word pety which means small. Initially, the word pet was used to describe a spoilt child or a favoured animal, and in 1818 the term became synonymous with the action of stroking or ‘petting’ another. However, as the presence of companion animals increased in British households at the height of the Victorian empire, ‘pets’ provided another representation of the conquest of the ‘wild’ and acted as symbols of increasing wealth following the industrial revolution (Ritvo, 1987; Turner, 2000). It is this perhaps uneasy association that has been picked up by contemporary debate and gives rise to discussion about the correct way to term ‘companion animals’. Tuan (1984) in his book Dominance and Affection: The Making of Pets argues that the very relationship between people and pets mirrors notions of inequality between humans and animals, allowing unashamed physical and behavioural modifications many of which have been detrimental to the animal's wellbeing, for example the Bubble Eye Goldfish and the Dachshund (Figure 1). Veterinary nurses are all too well aware of the debates surrounding the breeding of pedigree animals with specific anatomical features, an issue covered in a previous edition of The Veterinary Nurse (Young, 2011). It is certainly debatable to what extent society's attempts to modify animals as far away from their wild cousins refects people's perception of them as objects and a means to an end, rather than valuing them as ends in themselves. If animals are inherently perceived as means to an end by societies, what place does the role of animal metaphor in language play in reinforcing such a distinction?

The metaphorical animal

When examined closely, the use of animal terms, similes and metaphors in everyday communication demonstrates culture's ambivalent attitudes towards animals. In English, the term ‘animal’ is associated with socially disapproved behaviour but why is this the case? It is true that positive animal metaphors do exist however idioms such as ‘busy as a bee’ or ‘eagle eyed’ are significantly fewer in number in the English language (Dunayer, 2001). Animal terms of abuse work because they involve a common wisdom within a certain cultural and historical setting. The origins of such abusive and unpleasant metaphors that trivialize violence towards animals, such as ‘there's no use in fogging a dead horse’ and ‘there is more than one way to skin a cat’, are often forgotten, but are usually derived from endemic situations of historically acceptable cruelty (Smith-Harris, 2004).

Furthermore, animal-related words are part of a linguistic network of negative signifiers of the low social status of non-human animals (Dunayer, 2001). For example, the word ‘pig’ can only be meaningful when applied to humans as a term of derision if it is understood that pigs have of a lower-than-human status. Interestingly enough, companion animals are emotionally significant to humans and yet, for example, many abhorrent feline expressions exist; a point that may not be surprising given the shaky historical treatment of cats (Smith-Harris, 2004). This follows, in particular, their association with necromancy (a form of magic involving communication with the deceased) in their given role as witches’ familiars during the witch craze of the medieval age (Serpell, 2002). The fact now remains that all these expressions are so much a part of the English language that the violence that they condone or the human situations that the term ‘animal’ or related terms can effectively represent are commonly overlooked (Smith-Harris, 2004). In Coetzee's internationally celebrated 1999 novel The Lives of Animals, the central novelist character, Elizabeth Costello, laments the use of the language of the slaughterhouse to describe atrocities committed by the Nazis in World War Two. In the book, Costello suggests that such expressions as ‘they went like sheep to the slaughter’ and ‘they died like animals’ demonstrates that there is a subtle awareness of the brutalities inflicted on millions of non-human animals and use this as an appropriate linguistic representation for the murderous outcome of Nazi ideology (Coetzee, 1999). When it comes to the use of such terms and expressions in everyday language, does anyone stop to think about the reality behind those expressions and the negative connotations that they can reinforce?

From pet to person? Abandoning ‘it’

The previously discussed article in the Journal of Animal Ethics is not the first attempt to encourage people to reconsider their linguistic allusions towards other animals. In 1999, the American animal advocacy organization, In Defense of Animals (IDA), began a movement to replace the term animal ‘owner’ with animal ‘guardian’. This had some success in the United States, where currently a total of around 6000 000 Americans and Canadians are recognized as animal ‘guardians’ through the adoption of the term in of-ficial state and veterinary documentation (In Defense of Animals, 2011). The term guardian, according to IDA, is a better expression of the relationship between people and the animals they share their lives with. Additionally, it encourages people to respect animals as sentient beings by using language which does not reinforce an unequal power relation (In Defense of Animals, 2011). As David Nibert has stated, ‘language is yet another powerful force that both refects and conditions human perceptions and attitudes towards devalued humans and other animals’ (Nibert, 2002). By engaging in this debate not only are veterinary professionals creating avenues of discussion around the use of certain animal-related language but they are also beginning to question the status of animals in generally human-centred societies. Francione (2008) suggests that animals currently have ‘owners’ because they are legally defined as ‘property’ and not ‘persons’ even though it is recognized that animals have a degree of ‘personhood’ through a significant self-interest in avoiding suffering (Figure 2). This statement is relevant to veterinary practice, where various laws, for example the UK Animals Anaesthetics Act 1954 and the UK Animal Welfare Act 2006, are designed to control or prohibit certain potentially negative consequences to animals for creatures that can suffer.

Conclusion

Language contains contradictory terms regarding non-human animals because of the contradictory ways that people have relationships with them. As language is both prescriptive and descriptive it may be relevant for veterinary nurses who are obliged to respect and treat all patients humanely making animal welfare their primary consideration (RCVS, 2010), to reconsider the way that animals are related to verbally, both at work and in their wider lives. If animal nomenclature reveals the way animals are viewed, veterinary nurses can ensure that they do not employ negative terminology when it comes to the welfare of animals committed to their care. The adoption of the term ‘he’ or ‘she’ instead of ‘it’ to describe a patient and a re-evaluation of ‘animal language’ together with rigorous and compassionate nursing attention will go a long way towards the recognition of the animal ‘persons’ who veterinary nurses are privileged enough to serve in their daily, professional practice.

Key Points

- There is a current suggestion by some scholars that animal terms of discourse and animal metaphors are historically based on the denigration of animals.

- In Western societies, the three major influences of classical Greek thought, Biblical doctrine and Cartesian Dualism have biased humans over animals.

- The word ‘pet’ originates from a 16th century dialectical term meaning ‘small’ but some more modern connotations see the term bound up with human domination over animals.

- Language is not only descriptive but is also prescriptive; it can help to maintain relationships of inequality when relating to both other human beings and animals.

- Veterinary nurses should consider whether the language they use to describe animal patients recognizes the animal's status as sentient beings, and not as ‘property’, even though non-human animals are currently defined as ‘property’ in law.