All surgical wounds become contaminated by bacteria, but not all become infected. A critical level of contamination is required before actual infection occurs. Quantitatively, it has been shown that if a surgical site is contaminated with >105 microorganisms per gram of tissue, the risk of surgical site infection is markedly increased (Krizek and Robson, 1975). It has been suggested, however, that this figure may oversimplify the situation somewhat, as there are many factors involved in determining whether a level of wound contamination will result in infection (Baines et al, 2012), including the host's own level of resistance.

Bacterial contamination during a surgical procedure can originate from endogenous sources (resident flora of the patient) or exogenous sources (environmental or temporary skin contaminants). However the patient is considered the major source of contamination of the surgical wound, with endogenous staphylococci and streptococci reported as frequently cultured organisms from surgical site infections (SSIs) (Baines et al, 2012).

Skin harbours two major groups of microorganisms; transient and residual flora.

Transient flora

Transient (or contaminating) flora do not normally colonize skin. They are acquired by contact with people/animals or the environment. They are generally easy to remove from the skin through the physical action of scrubbing, and can be almost completely eliminated by effective antiseptics (Baines et al, 2012).

Resident flora

Resident (or colonizing) bacteria live on normal skin and help protect it from invasion by pathogenic species. They have minimal pathogenicity, but may cause infection following surgery or other invasive procedures (Gregory, 2005). It is not possible to completely eliminate resident flora from the skin, as approximately 20% of these microorganisms are inaccessible to skin disinfection as they are sequestered in the deeper layers of the skin, within the hair follicles and sebaceous glands (Warner, 1988). Rebound growth of bacteria deep within the skin also occurs during surgery. Rebound growth is defined as the tendency of a microorganism to repopulate an area following decontamination, over a much quicker period of time than the original colonization took place (Scowcroft, 2012). This local bacterial re-colonization of surgical sites represents a significant risk to wound contamination (Owen, 2007), thus the selection of a skin preparation agent with good residual activity is desirable.

Although the skin will never be considered sterile, the proposed incision site and the area surrounding it should be as free from microorganisms as possible prior to surgery. This is achieved via a variety of means as described below.

Bathing

Pre-operative grooming and bathing of a patient may be advocated in certain circumstances (e.g. tibial plateau levelling osteotomy or hip replacement) in order to remove excess hair, skin scales and external parasites. This task may be delegated to the owner, however there may be a problem with compliance therefore it may be better performed by the ward staff as it enables the condition of the skin to be checked. Any irritation or abrasion on or near to the proposed incision site might be a contraindication to the surgical procedure and should be reported to the surgeon (Phillips, 2004).

However, pre-operative bathing is a controversial subject as it has been shown to temporarily increase exfoliation of skin squames, increase hair shedding and produce rebound population of resident micro-bial flora (Gasson, 2007). The decision to bathe prior to surgery, therefore, is probably best based on the degree of contamination of the individual patient and the procedure being performed.

Hair removal

Hair is a gross contaminant and significant reservoir for microbes and organic debris. It also acts as a foreign body if it gains access to the surgical incision.

Whether clipping is carried out pre or post induction of anaesthesia generally depends on a number of factors, including patient compliance, accessibility to the surgical site, condition of the patient (elective vs emergency) and staff numbers. In critical patients (e.g. gastric dilation and volvulus), a rough clip prior to induction may be advocated as it will decrease the length of time that the patient is anaesthetized. In most other circumstances, pre-clipping is to be avoided as it has been shown to increase bacterial load on the skin, leading to a threefold increase in infection rate in one veterinary study (Cimino Brown et al, 1997). In addition, studies have concluded that the rate of skin infection is proportional to the duration of time the hair was removed and therefore it is contraindicated to remove hair more than 12 hours before surgery commences (Joyce, 2006).

Hair removal is necessary for most surgical procedures and can be achieved by use of razors, depilatories or clippers.

Razors

The act of shaving a patient with a razor prior to surgery has all but ceased in veterinary surgery. However, some personnel do still remove gross hair with clippers and then use a razor to produce minimal stubble. There is much evidence, however, to support the fact that this act is indeed detrimental to the patient. Even the most expertly performed shaves result in unseen epidermal cuts and nicks. Shaving can provide entry for resident and transient microorganisms on the epidermis and hair shafts, and can increase the risk of wound infection (Lazenby et al, 1992).

Depilatories

Depilatory creams may occasionally be used, however they are generally not effective given the length of the hair, not to mention the mess they cause. They may be useful for removing fur from rabbits, chinchillas and other small mammals but not from dogs and cats. Hair removal creams may also be associated with cutaneous reactions (Baines et al, 2012).

Clipping

Clipping is the most commonly employed method and is associated with the lowest incidence of SSI (Gasson, 2007). However, poor clipping technique will result in unnecessary trauma to the skin (clipper rash) and increase the chance of SSI due to colonization of lacerations and abrasions by resident microbes (Owen, 2007).

Prior to commencing clipping, it is important to be aware of the surgical approach to ensure clipping is carried out effectively. Ascertain limits — allow for extension of incisions and drain placement. An area of 15–20 cm around the proposed incision site is recommended to prevent hair contamination (Shellim, 2007). Naturally, in the case of exploratory procedures, a larger diameter may need to be clipped to allow for the surgical field to be extended for better access. The area clipped needs to be neat, tidy and symmetrical, as this is what the owner first notices and the client's impression of the clip's appearance may influence their impression of the entire practice and staff.

To minimize the risk of hair particles contaminating the surgical field, clipping should be performed outside theatre, usually in the preparation room, using a designated surgical clipper blade.

During clipping, the clippers should be held in a pencil grip fashion as this will permit the greatest amount of control and manoeuvrability. They should also be held fat against the skin for the closest shave. Great care must be taken not to traumatize the skin when bony prominences, for example the spine and joints, and thinned areas of skin such as the groin or axilla are encountered. Unless the patient has a very short coat, hair is generally best removed via a two-stroke method. The bulk of the hair is removed by clipping in the direction of the lie of the hair (Figure 1). A closer clip is then achieved by clipping against the direction of the hair; this enables a close surgical clip, but with minimal skin trauma (Baines et al, 2012).

When clipping around open wounds, contamination by loose hair and dander can be minimized by covering the area with saline-moistened gauze swabs or application of a sterile water-soluble gel to the area (Shellim, 2007).

After clipping, the patient and the area need to be thoroughly vacuumed to remove any loose hairs. This is because loose hair can be a source of contamination and if not removed may make its way into the operating theatre. Brushing away loose hair from the clipped site with a hand is not as effective as vacuuming, and releases hairs into the environment. A sticky roller can be useful in removing the last few loose hairs prior to commencing skin preparation (Shellim, 2007).

Maintenance of clippers

Clippers and their blades should have the recommended routine maintenance performed in order to extend the life of the equipment while achieving optimal performance. The blade should be brushed clean of any hair, lubricated, disinfected (or sterilized) after use on a contaminated site and examined for any chipped or missing teeth, which will pull on the skin and may cause clipper burn. In order to prevent blade burns, lubricants and coolant sprays should be applied to the blade and repeated throughout the clipping procedure. To preserve clipper blades, a size 30 blade may be used to remove longer hair followed by a size 40 surgical blade, which clips to 1/10 mm (Joyce, 2006).

Following removal of the hair, the skin needs to be prepared with a suitable skin antiseptic.

Surgical skin preparation

The purpose of skin preparation is threefold:

- Removing soil and transient microorganisms from the skin

- Reducing the resident microbial count to sub pathogenic levels in a short period of time and with the least amount of tissue irritation

- Inhibiting rapid rebound growth of microorganisms (Association of Peri-operative Registered Nurses, 1997)

The process of skin preparation removes bacteria by both mechanical and chemical means. The mechanical process involves the application of skin antisepsis solution with adequate friction of the applicator to ensure that all the cracks and fissures in the skin are sufficiently coated with the solution (Scowcroft, 2012).

The chemical process involves both the destruction of microorganisms and the prevention of rebound colonization after cleansing (Scowcroft, 2012).

The first agent used in the surgical preparation of a patient is a ‘scrub' product. This solution contains a soap or detergent base therefore creating a lathering appearance when used.

According to Baines et al (2012) the ideal scrub solution should:

- Be lathering in order to remove dirt and grease

- Have broad spectrum bactericidal, virucidal, fungi-cidal and sporacidal properties

- Rapidly kill microorganisms

- Be non irritating to the skin

- Be economical.

Commonly used scrub solutions and their properties are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Commonly used scrub solutions and their properties

| Chlorhexidine | Povidone-iodine | Alcohol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mode of action | Works by disrupting the cell membrane and precipitating the cell's contents | Rapidly penetrates the cell wall and inhibits protein synthesis by forming protein complexes | Denatures proteins and inhibits metabolites necessary for cell division |

| Efficacy | Broad spectrum, but less effective against Gram-negative than Gram-positive bacteria. Virucidal. Less activity against fungi | Broad spectrum. Active against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungi, yeasts, all enveloped viruses and some non-enveloped viruses | Broad spectrum of bactericidal activity and good action against fungi and mycobacteria. Isopropyl alcohol is more effective against bacteria whereas ethyl alcohol has more activity against viruses |

| Contact time | Minimum contact time of 3 minutes. 3–5 minutes recommended for good residual activity | Iodophors must be in contact with the skin for a minimum of 2 minutes to kill bacteria. A minimum of 15 minutes is required for sporicidal action | Minimum 2 minutes before evaporation to have a maximum bactericidal effect |

| Residual activity | Good residual activity as binds to the stratum corneum | Minimal residual action | No residual action. Improved activity when used with chlorhexidine |

| Efficacy in the presence of organic matter | Effective in the presence of organic matter Inactivated by the presence of organic matter. | Inactivated by the presence of organic matter. Skin should be cleaned prior to application | Inactivated by the presence of organic matter. Skin should be cleaned prior to application |

| Precautions for use | Irritant to the cornea, ototoxic especially if it enters the inner ear where it may cause sensorineural deafness and meningiotoxic. This agent is contraindicated for ocular and facial asepsis (Phillips, 2004) | Low pH (3–5) is tolerated by epithelium but not endothelium. Povidone-iodine (without detergent) is widely used for ocular skin preparation within veterinary practice. It is used for ocular and facial asepsis in human surgery although Triclosan is increasingly considered the agent of choice (Association of Surgical Technologists, 2008) | Must not be used on open wounds or mucosal surfaces. Highly flammable |

Care must be taken as Gram-negative bacteria, particularly Pseudomonas species, can multiply in some dilute antiseptic solutions. Therefore, such solutions should be dispensed freshly from concentrated stock solutions into 500 ml sterile containers for daily use (Gasson, 2007). Invicta Animal Health are the exclusive veterinary distributor of Chloraprep®, a single use, easy to apply sterile skin preparation system which may help overcome the problem of contaminated solutions. The sterile solution of 2% chlorhexi-dine and 70% isopropyl alcohol is maintained in a glass ampoule within a protective outer case. In order to prevent contamination, the patented design ensures personnel do not come into contact with either the contents or the patient's skin during aseptic skin preparation. See www.invictavet.com for further information.

Before surgical skin preparation commences, the skin should be free from gross contamination (i.e. dirt, soil, or any other debris). Non-lint producing gauze swabs are preferable to cotton wool for the application of skin prep solutions as cotton wool is prone to leaving fibres on the skin (Figure 2.). These may subsequently find their way into the surgical incision, potentially transferring skin microbes with them (Anderson Manz et al, 2006).

The wearing of surgical gloves during skin preparation is advisable as it decreases the risk of contamination by the operator's hands; the gloves need not be sterile during the initial stages of the preparation procedure (Baines, 1996).

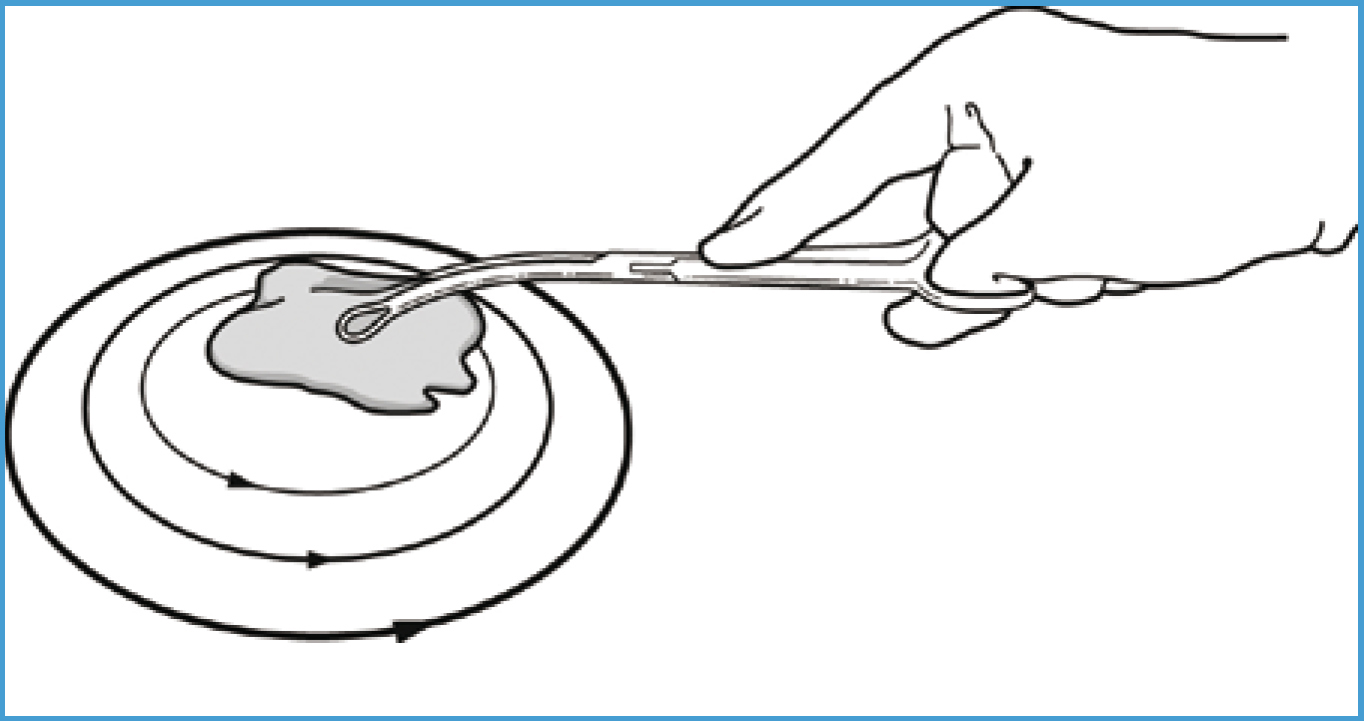

The target pattern is frequently used to prepare the surgical site; it resembles a target or bull's-eye, hence the name (Figure 3.). The selected disinfectant is applied at the proposed incision site, working outwards in concentric circles until the outer margins are reached. The disinfectant is left for the required contact time and then removed with swabs, again working from the centre outwards.

Reports from human literature state there is no evidence to support the use of concentric circling, suggesting a backwards and forwards motion to be as effective (Care Fusion, 2010). Regardless of the pattern used, the procedure should be repeated, usually three to five times, or continued until the skin appears completely clean, and the swab yields no dirt, and for the length of time recommended by the disinfectant's manufacturer.

Preparation of a limb differs in that it is suspended and antiseptic is applied to the distal limb, working distal to proximal, i.e. toes to axilla or inguinal region (most to least contaminated area) (Joyce, 2006). The full circumference of the limb should be clipped and prepared to enable surgical personnel to fully visualize and manipulate the limb throughout surgery. After the hair has been removed from the surgical site, any hair remaining on the foot should be covered. This is because animals' feet harbour a high resident bacterial population; therefore, if access is not required the foot can be excluded by applying a water-impermeable material, thus preventing bacterial strike-through (Joyce, 2006).

Irrespective of the area prepared, excessive pressure must be avoided as it may abrade the skin; such abrasions become rapidly colonized by the host's resident flora (Baines et al, 2012). Care must also be taken not to over wet the patient. There should be just sufficient water to produce lather. Too much water may result in dilution of the agent, reduced efficacy, and potential for heat loss (Baines, 1996). Pre-warming of the scrub solution prior to application is advocated to further minimize heat loss (Robertson, 2007).

Rinsing agents

After application of a scrub product, a rinsing agent is required to remove the detergent. A commonly used agent for rinsing is 70% isopropyl alcohol, as this is effective against most Gram-negative bacteria. Alcohol can be used with either povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine scrub, however residual properties of chlorhexidine are reported as enhanced when used with 70% isopropyl alcohol. The application of alcohol followed by a final combined solution of 15 ml water/10 ml chlorhexidine/75 ml alcohol has been found to provide residual antimicrobial activity during the surgical procedure (Joyce, 2006).

Povidone-iodine, however, does not show any increase in residual activity (Busch, 2006).

Care must be taken when using alcohol as it coagulates proteins, which contraindicates its use on open wounds and mucous membranes. The extreme cooling effect that results from rapid evaporation is also detrimental as it will predispose the patient to hypothermia (Busch, 2006).

When preparing the abdomen of a male dog, if the prepuce will be present in the draped surgical field, consideration should be given to flushing this in order to remove potential contaminants. Dilute chlo-rhexidine solution (one part chlorhexidine to 50 parts water) has been suggested for this procedure (Neil-haus et al, 2010). Likewise it is advisable to flush the vulva of bitches undergoing perineal surgery (Baines et al, 2012).

Sterile skin preparation

The final sterile scrub is performed in theatre once the patient has been appropriately positioned on the operating table. It is difficult to maintain asepsis of the proposed incision site when moving the patient from the prep area into theatre as personnel will likely have some contact with the intended surgical site during transportation and positioning.

The use of sterile water or saline, sterile gauze swabs and either sterile sponge-holding forceps or a sterile gloved hand is highly desirable for the final preparation of the patient (Baines et al, 2012).

The same technique and antiseptic agent used for the initial skin scrub should be used, however this time a solution or ‘paint' is used rather than a ‘scrub' agent. Solutions are from the same chemical family as the scrub agent but they do not contain a detergent. Using a scrub and solution from a different chemical family is counterproductive as the two agents may inactivate each other (Williams, 2000). Thus povidone-iodine scrub should be followed by povidone-iodine solution. Likewise, chlorhexidine scrub should be followed by chlorhexidine solution.

Draping

Finally, sterile surgical drapes are applied to isolate the prepared surgical site in order to create a sterile field. Drapes create a barrier to the translocation of bacteria to the sterile area. Impervious disposable materials are more efective at this than the traditionally used fabric drapes which are often associated with the transfer of moisture and accompanying bacteria (strike-through) from above and below the drape (Baines et al, 2012).

Conclusion

SSIs are an inherent risk during surgery and many of the infections that develop are likely to be non preventable. The veterinary nurse has a duty of care to their patient to recognize such risks and reduce them wherever possible. The principle of surgical asepsis is the complete exclusion of microorganisms from the surgical wound. However, as this is not possible, the emphasis needs to be on the design and rigorous adherence to evidence-based infection control protocols, intended to reduce the level of contamination such that the host's own defences can prevail.

Key Points

- All surgical wounds will become contaminated but not all will become infected.

- The patient is considered the major source of contamination of the surgical wound.

- Skin harbours both transient and residual flora.

- Lacerations and abrasions are rapidly colonized by resident microbes.

- Design and rigorous adherence to infection control protocols is essential.