References

Best practice parasite prevention in the travelling pet

Abstract

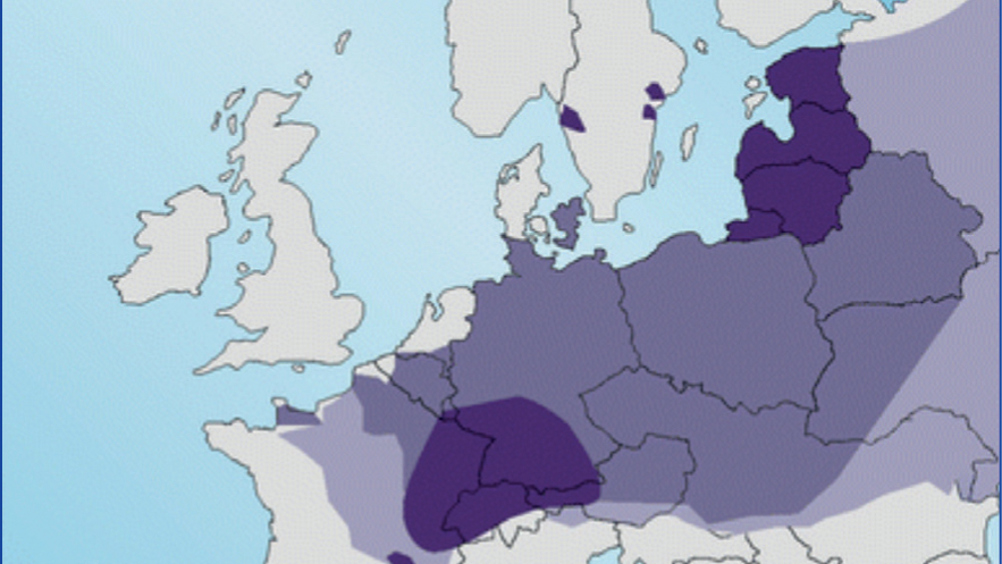

The number of pets travelling under PETS is increasing year on year, while at the same time, climate change and increased movement of people is affecting parasite distribution across Europe and the wider world. Accurate parasite prevention advice to clients taking their pets abroad is therefore vital to keep pets and owners safe. It is also an important aspect of UK biosecurity and the prevention of exotic parasites and vectors establishing. Although it is the role of the Official Veterinarians (OV) to issue passports and ensure legal pet travel requirements are followed, nurses also play a pivotal role in discussing parasite risks with clients and ensure accurate up to date preventative advice is given. This article summarises the risks posed by some of the major parasites and vectors across Europe and effective practical prevention advice to give to clients.

Since the Pet Travel Scheme (PETS) was relaxed in 2012, pet travel has increased year on year, with 287 016 UK dogs travelling on the PETS in 2017, up from 164 836 in 2015. This increase has occurred at a time of increased human migration and climate change, providing favourable conditions for the rapid spread of parasitic diseases and their vectors. This makes effective parasite prevention advice for travelling pets based on the most recent parasite distributions vital to keep pets and owners safe, while also minimising risk to national biosecurity. It is the role of Official Veterinarians (OVs) to issue pet passports and ensure legal requirements are met, but veterinary nurses also play a vital role in pet travel clinics, risk assessment and ensuring all parasite protection needs are covered. Some of the parasites encountered abroad will be ‘the usual suspects’ forming the core of pet travel advice and will be familiar to UK veterinary surgeons and nurses involved with pet travel clinics. In addition however, new parasites are also emerging which will be less familiar to most with potentially fewer licensed preventative products. All of these threats in combination must be considered when giving best practice pet travel advice.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.