Diabetes pathophysiology and disease management

Abstract

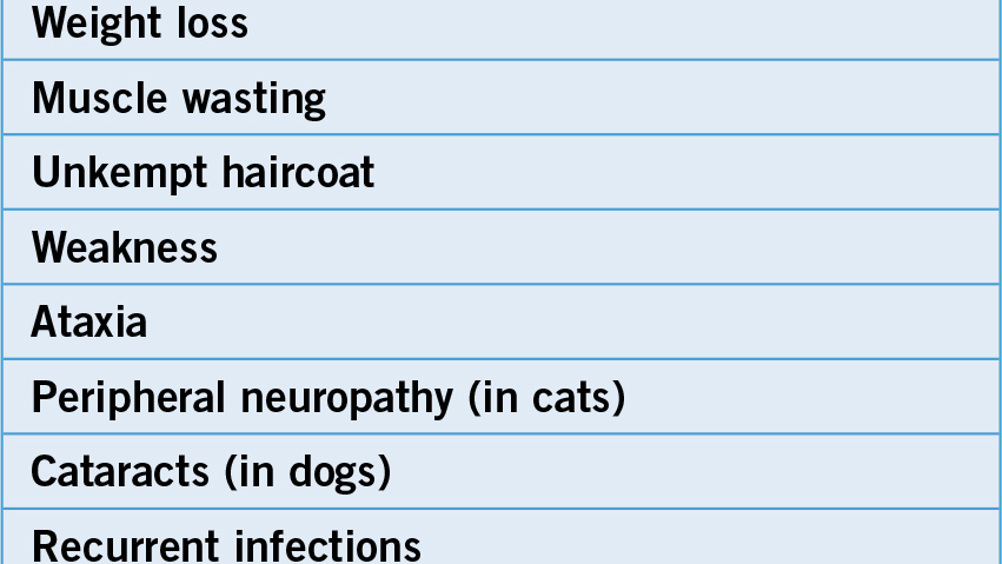

Diabetes is a disease that presents in many different forms, but diabetes mellitus is the most common form seen in dogs and cats. Insulin dependent diabetes mellitus is more common in dogs than cats and non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus is more common in cats than dogs. The incidence of diabetes varies depending on the species, age, physical attributes, genetic make up and gender of the animal. Clinical signs almost always include polyuria and polydipsia, but can also include polyphagia, weakness, weight loss, unkempt haircoat and changes in behaviour, among others. There are a number of successful treatment strategies that can enable the diabetic dog or cat to lead a long fulfilling life. Many of these treatment plans require careful monitoring of blood glucose, daily insulin injections and modifications in diet and lifestyle habits. A veterinary nurse who has a good foundation on diabetes disease pathophysiology, treatments and management strategies is not only essential in caring for hospitalized diabetic patients, but is also critical for helping to alleviate pressure on clients who must bear the responsibility of managing their diabetic pet at home.

Diabetes is one of the most common endocrine diseases seen in companion animal veterinary practice, but it can still be quite a challenge to effectively educate clients in the care of their diabetic pet. Veterinary nurses play a large role in the successful management of diabetic patients by carrying out such tasks as collecting diagnostic samples, administering medications, providing skilld nursing care and through advising pet owners. To fulfill these nursing roles, it is important that veterinary nurses have a good foundation of knowledge in the diabetic disease process as well as being well versed in some of the most common treatment and management protocols.

Diabetes is an endocrine disease affecting some of the glands that regulate metabolism. There are two main forms of the disease, diabetes insipidus and diabetes mellitus:

Diabetes mellitus is far more commonly seen in veterinary clinical practice than diabetes insipidus, and, therefore, will be the primary area of focus for this article.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.