The focus in the UK on the parasite E. multilocularis has largely been associated with maintaining the requirement for pre-entry treatment of dogs, which of course was successfully maintained with the rule changes introduced in January 2012. While that was a milestone it was by no means the end of the story. The range of the parasite continues to increase dramatically in Europe, there is some increase in understanding of the risk factors associated with human infection and it is acknowledged that this infection has a zoonotic impact even in developed, wealthy European countries. Current EU focus appears to be on ensuring that those countries currently fortunate enough not to have the infection present in their country have a sufficiently rigorous scientific process to prove that the country remains free of infection: there appears to be no initiatives to control the infection in countries where it is endemic. Owners with dogs and cats travelling to the areas where this infection is now endemic should be aware of the risk and take suitable measures to prevent zoonotic infection and to control infection in their pets. This review does not go systematically through all aspects of the infection and these details can be found on, for example, the www.esccapuk.org.uk website.

Update on the range of E. multilocularis

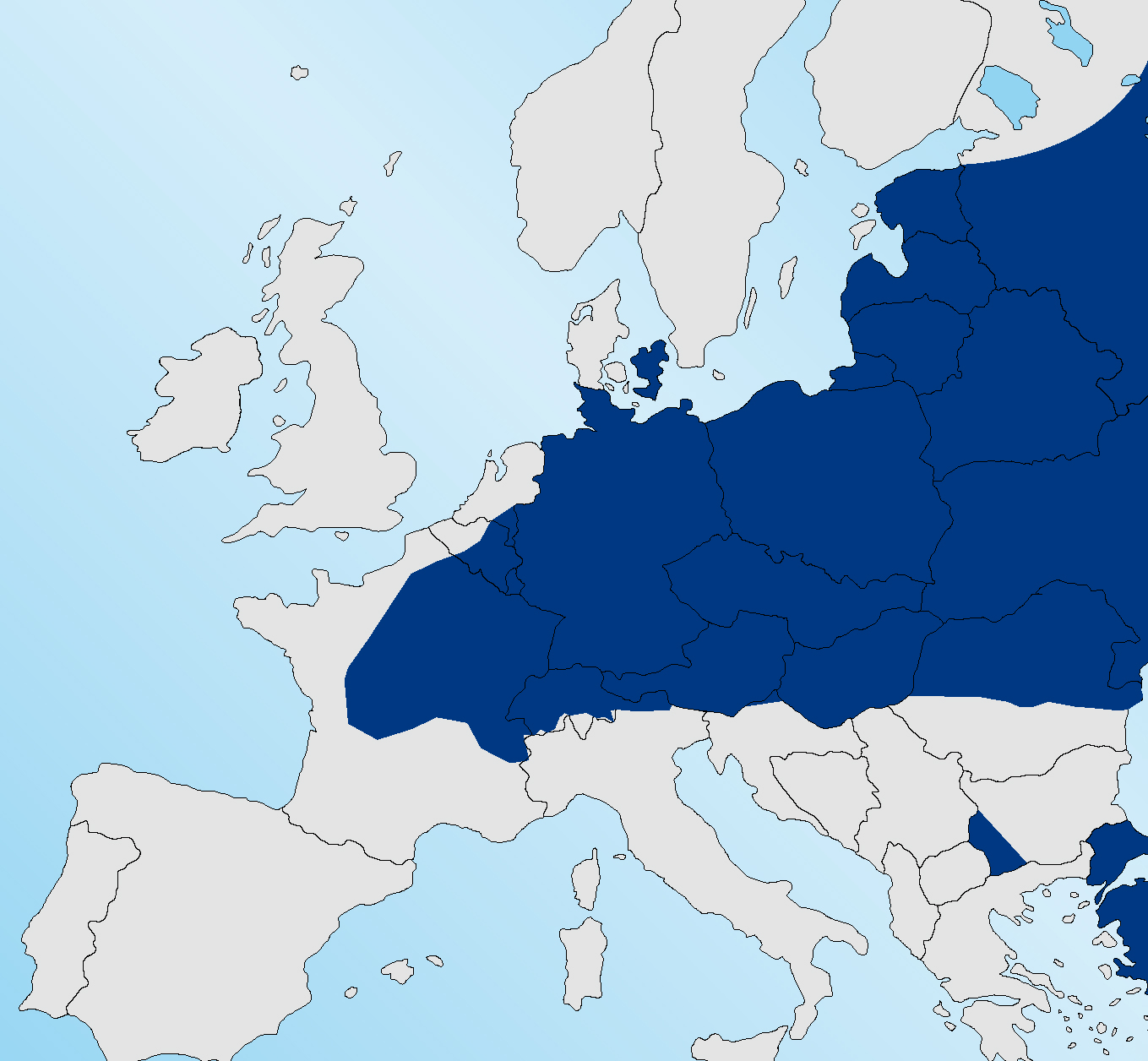

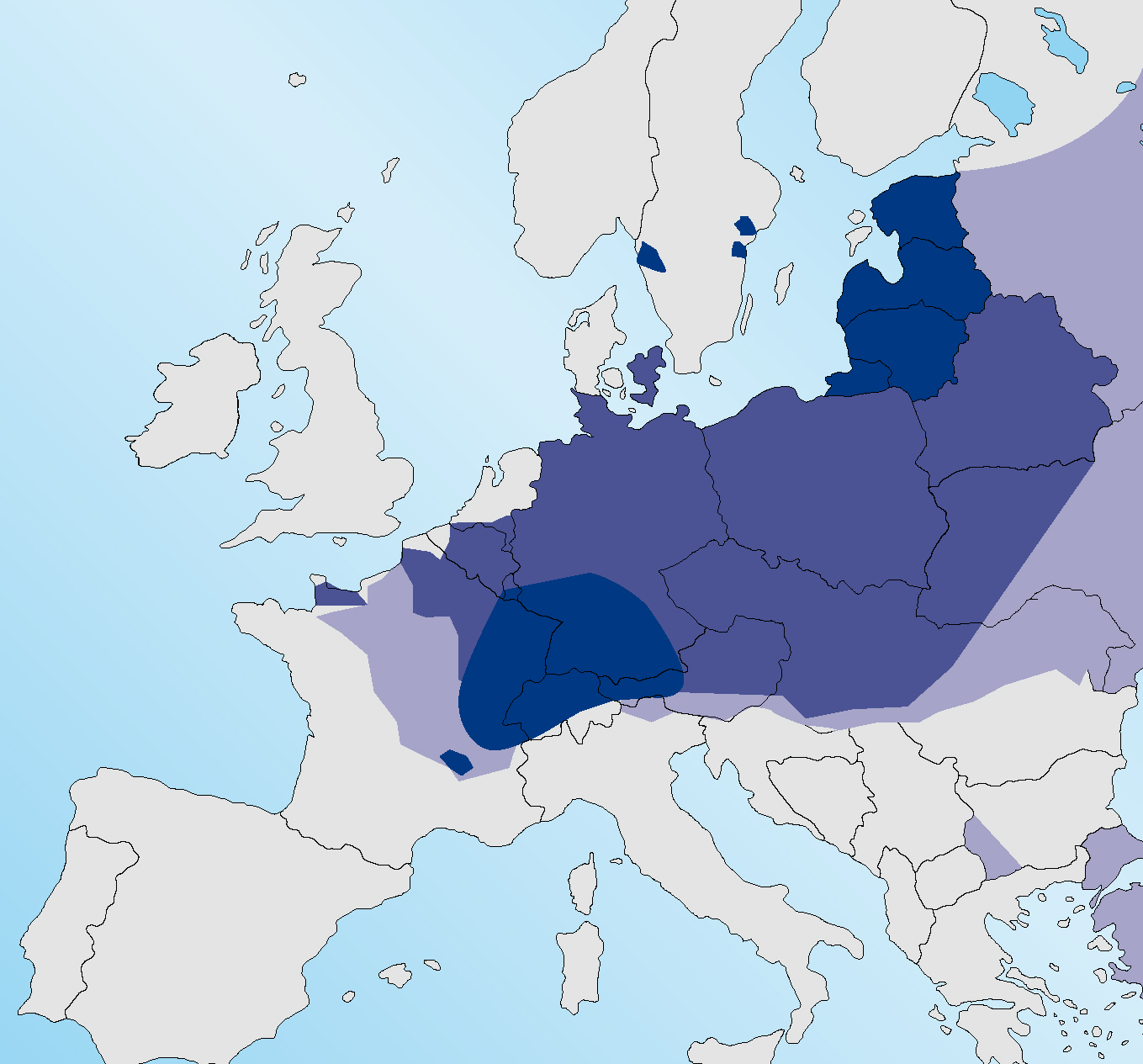

Figure 1 shows the range of E. multilocularis in foxes in 2010 (ESCCAP, 2010) with infection absent from Sweden, the Jutland peninsula of Denmark and the north western coast of France. It is now present in each of these areas (Figure 2) with areas of Normandy highly endemic for infection (Deplazes, 2013). The infection is reported to be endemic in foxes in the southern Netherlands (van Knapen, 2014). Affected areas of France include regions close to ferry embarkation locations, which has several implications for travellers from the UK. This may increase the risk of dogs or cats acquiring infection in the window between mandatory treatment and travel. Many travellers to the Continent travelling only as far as Normandy or the western coast of France, Belgium or the Netherlands were unaffected previously as they were not entering areas where the infection was endemic. This ‘buffer zone’ in the western edge of the Continent no longer exists.

The increase in range appears to be due, in part at least, to an increase in the fox population on the Continent, following the very successful rabies eradication campaign conducted during previous decades (Hegglin et al, 2008).

As in the UK, urban and suburban areas have been colonised by foxes and this means that infected foxes can be living in close proximity to large numbers of human dwellings. It is believed that these areas may represent a particularly high risk of human infection (Hegglin and Deplazes, 2013). The tapeworm is now well established in Paris and its surrounding area (Piarroux et al, 2013).

Infection in cats

There has been much debate about cats and E. multilocularis. The European Union takes the view that they are not epidemiologically important as infection establishes far more robustly in foxes and then to a lesser extent in dogs than cats (Sanco, 2012). Maturation of worms and egg output is considerably better in foxes and dogs than cats, with some studies reporting few worms maturing or producing thick shelled eggs in cats (a sign of maturity and infectivity) (Thompson et al, 2006). Nonetheless there is evidence of feline infection with an epidemiological survey of faecal samples from cats and dogs from Germany, The Netherlands and Denmark, reporting prevalence of infection in cats and dogs was almost identical at 0.24–0.25% (Dyachenko et al, 2008). While there is no doubt that infected dogs and foxes are responsible for almost all of the eggs being shed into the environment and that dogs are far more likely than cats to have eggs trapped within their coats (ESCCAP, 2010), there is concern that, since cats are more likely to hunt for rodents and to bury their faeces in gardens, there is a risk that cats could contribute to the epidemiology of domestic infection. In some studies of the activities associated with zoonotic infection, owning a cat has presented as a risk factor. Other authors reject the cat as playing a role and it has been suggested that, since owning cats, living in rural areas and gardening are commonly associated factors, there is a high risk of confounding amongst these factors, making it difficult or impossible to identify the most significant risk factors. For this author the jury remains out on this question and applying the precautionary principle, cats should be included in monthly treatment with an effective cestocide containing praziquantel or equivalent while they are staying or living in any area where the infection is endemic and they have access to the outdoors.

Assessing of the risk of E. multilocularis infection

A number of studies have been conducted to examine associations between alveolar echinococcosis in humans and possible risk factors (Hegglin and Deplazes 2013). Dog ownership, collecting wood, living in a farm house or being a farmer were identified as risk factors by Kern et al (2004). Cat ownership and hunting were identified as risk factors by Kreidl et al (1998). Piarroux et al (2013) identified farmers and other rural dwellers and non-rural gardeners as being most at risk in departments of France where the infection is most common. The number of cases in each study is relatively small and the risk factors are confounded by many individuals in rural areas being exposed to more than one risk factor.

Diagnosis of E. multilocularis infection in humans

Alveolar echinococcosis develops almost exclusively in the liver, although not all infective eggs ingested result in a viable alveolar cyst (Figure 3 and Figure 4); some will develop for a time and then atrophy. When the cyst continues to develop, it will typically begin to cause clinical signs consistent with a hepatic space occupying lesion some 10–20 years later, thus there is a considerable lag time between infection and apparent disease (Atanasov et al, 2013). Presenting signs can include severe pain consistent with acute pancreatitis. Biopsy is not normally recommended as this may allow release of the parasitic metacestodes into surrounding tissue and hence metastatic spread of the infection. The lesions can be visualised and identified using contrast computer tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Typically the cysts have a multilobular structure with local invasion of other organs. Rarely the cysts may have an apparently unilobular appearance consistent with that of hydatid cysts. The diagnosis can be confirmed by serology, histology following resection and polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Effects of E. multilocularis infection on humans

As the cystic structure increases in size it may develop as a space occupying lesion in the liver alone or may invade surrounding tissues and cause fibrosis and adhesions in the area. Occasionally a portion of the cyst breaks off and establishes at a distance from the primary cyst.

Patients may present with abdominal pain and jaundice (Atanasov et al, 2013) but there is a wide variety of possible symptoms depending on the size of the cysts, their location and the type and degree of tissue damage (Pawlowski et al, 2002).

Despite the availability of treatment, the average life expectancy of men and women following infection is still reduced by 3.6 years for men and 2.5 for women in Switzerland. While this is a huge improvement on the survival rates in earlier decades, it still represents a significant reduction of life expectancy (Torgerson et al, 2008).

Treatment of human infection

The preferred treatment for alveolar echinococcosis is total resection and removal of all affected tissue when this is possible. In some cases where the cyst is extensive, ill-defined or invasive of surrounding tissues then total resection may not be possible. Following surgery, long-term benzimidazole therapy is normally provided to control any remaining cystic material (Atanasov et al, 2013).

Prevention of human infection

Owners with dogs and cats travelling to the areas where this infection is now endemic should be aware of the risk of infection to themselves and their pets. Eggs in the environment are immediately infective to potential intermediate hosts and humans should take particular care if, for example, their dog has rolled in fox faeces and needs to be bathed. Prevention of pets hunting rodents, regular treatment of both dogs and cats with praziquantel or equivalent and wearing gloves while gardening are measures that can help reduce the risk of human infection. Other general good public health advice such as educating children to wash their hands before eating (ESCCAP, 2010), removing dog faeces from public places and covering sand pits will further assist in reducing the risk of human infection in the areas where infection is endemic (ESCCAP, 2010).

E. multilocularis control

Control of E. multilocularis is envisaged as difficult if not impossible in areas where the infection is established in the rodent and fox populations. Large scale culling of foxes together with bait cestocidal treatments are two of the most practical means of reducing, if not eliminating, the infection. Restricting access of dogs and cats to rodents, minimising contact between people and foxes and information campaigns may all be useful in an integrated control strategy (Ito et al, 2003). In the event that total control was not achieved, which is the most likely outcome, bait treatment would have to be repeated at regular intervals. Small scale trials have shown that baiting can reduce the intensity of infection in foxes in a local area (Hegglin and Deplazes, 2013). Despite the lethal nature of untreated infection in humans and the cost of human treatment, since each human infection has a lag time of about 10 years, any action to prevent infection in humans would not show any cost savings for about a decade. Therefore, ironically, the nature of the infection in humans may fail to motivate politicians in the way that a viral infection that kills its victims rapidly is able to do.

Public information has been provided in countries where infection is endemic to a greater or lesser extent (Hegglin et al, 2008). In some countries scare tactics have been counter productive, while clear warnings about the risk and how best to reduce it have been better received.

Parasite control in dogs and cats in the peri-domestic environment together with hygienic measures such as hand washing before eating are effective measures to reduce risk that pet owners and other members of the public can adopt on a personal basis.

Conclusion

Those travelling to Continental Europe, with or without pets, should be aware of the increased range of E. multilocularis in Europe and take appropriate action to prevent their own infection and to ensure control in pets by regular praziquantel treatment where there is a risk of the pet being infected in those areas where infection is endemic in the fox population. Care should be taken by travellers to ensure the infection is not introduced to the UK as its presence would cause the cessation of permission from the EU to impose mandatory treatment prior to entry and would force a change of attitudes to pets and foxes in the UK.