Cats are known to exhibit stress during hospitalisation within veterinary practice. Although studies have previously looked into reducing stress for cats in rescue centres (McCobb et al 2005; Kry and Casey, 2007; Godijn, 2013; Moore and Bain, 2013; Vinke et al 2014; Arhant et al, 2015) and catteries (Kessler and Turner, 1997; Rochlitz et al, 1998), there is less literature for those in veterinary practice where it could be argued that cats experience unique stress due to illness, medical or surgical procedures (Trevorrow, 2013; Cherry, 2014; Hewson, 2014; Ellis, 2015).

Hideaways in the form of igloo beds, boxes or other structures are often recommended as a way of reducing stress for cats in general. Most studies are in agreement that this works (Kry and Casey, 2007; Carney et al, 2012; Ellis et al, 2013, Godijn, 2013; Moore and Bain, 2013; Trevorrow, 2013; Hew-son, 2014; Vinke et al, 2014; Ellis, 2015), but there seems to be limited research determining whether one type of hideaway is any better at reducing stress than another. Cats Protection recently developed the Feline Fort with the recommendation for its use within veterinary practice, which presented an opportunity to trial it against an alternative.

The research aimed to determine whether hideaways reduce stress for inpatient cats and determine if the Feline Fort does this any better than a cardboard box, which is a cheap and disposable alternative.

Literature review

For the purposes of this study the definition of stress is a state of tension, elicited by a perceived threat to homeostasis and measured by the animal's response via behavioural and neuroendocrine pathways (Moore and Bain, 2013; Godijn, 2013). In evolutionary terms stress can be advantageous; the behavioural and physiological response helps preserve homeostasis (Godijn, 2013). However, when a trigger evokes an event or situation and that cannot be controlled or escaped from, such as a feline hospitalised within cage, it can prolong these responses and lead to what can be called stress.

Cats are extremely sensitive to their environment (Carney et al, 2012) as they are not a social species and are territorial by nature (Cherry, 2014). They have clear body language signifying stress, such as ear position, fully flattened back of head, wide eyes with dilated pupils and tail close to body, and a reduction in maintenance behaviours (Ellis et al, 2014; Rehnberg et al, 2015). Complicating this is that individual cats respond differently to stress as a result of previous experience, age and gender (Rehnberg et al, 2015) as well as genetics (Buffington, 2015) and personality. Hiding is a response demonstrated by cats as a way of coping with stress (Ellis et al, 2013; Hewson, 2014; Stella et al, 2014).

Cats that are hospitalised within a veterinary surgery represent a unique population of stressed individuals due to illness, medical or surgical procedures, in addition to novel environment, unfamiliar odours, sights and sounds, as well as unpredictable routine and unfamiliar carers (Stella et al, 2013). Cats that are stressed can be difficult to examine, and stress can complicate diagnosis due to its effect on blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate and temperature (Quim-by et al, 2011). In addition physiological responses which can be exacerbated by stress, such as hyperglycaemia (Carney et al, 2012), can lead to prolonged recovery. It is clear that reducing stress in hospitalised feline patients is vital.

Veterinary staff can help reduce stress experienced by hospitalised cats in a number of ways including providing cat only wards, slow and quiet handling, and by using synthetic pheromones (Rodan and Folgar, 2010; Rehnberg et al, 2015). Additional methods can be found in the American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) and International Society of Feline Medicine (ISFM) paper on feline friendly handling (Rodan et al 2011). One method often recommended is the provision of a hideaway to allow the cat to perform natural behaviour. Cats subjected to stress eliciting events or situations will often attempt to hide (Nibblett et al, 2015), especially when other coping mechanisms such as escaping are not possible, such as within a veterinary kennel (Ellis, 2015).

Kessler and Turner developed the cat stress score (CSS) in 1997; the CSS is based on behavioural and posture observations of the cat and has been used by researchers in studies on feline stress and the provision of hideaways in adoption, rescue and quarantine centres (Rochlitz et al, 1998; Gourkow and Fraser, 2006; Kry and Casey, 2007; Godijn, 2013; Moore and Bain, 2013; Vinke et al, 2014; Rehnberg et al, 2015), but with mixed results. Limitations within the various studies included that the cats also had access to an outside run (Kry and Casey, 2007), heated hideaway (Rochlitz et al, 1998) and the kennel included toys and owner-scented bedding (Moore and Bain, 2013; Rehnberg et al, 2015). Only one of these studies concluded that the use of a hideaway did not lower stress levels (Moore and Bain, 2013), but in this study the cats were taken to a different room in which the scoring took place. In 2014 Cats Protection developed the Feline Fort (Figure 1), a three piece unit consisting of a step, table and hideaway (width 39 cm x depth 41 cm x height 30 cm). The hide is designed for use by itself and Cats Protection advocate its use for veterinary inpatients (Cats Protection); however as far as the authors are aware there are no studies testing the efficacy of the Feline Fort within the veterinary environment compared with alternative options, some of which are cheaper alternatives such as a cardboard box.

Methods

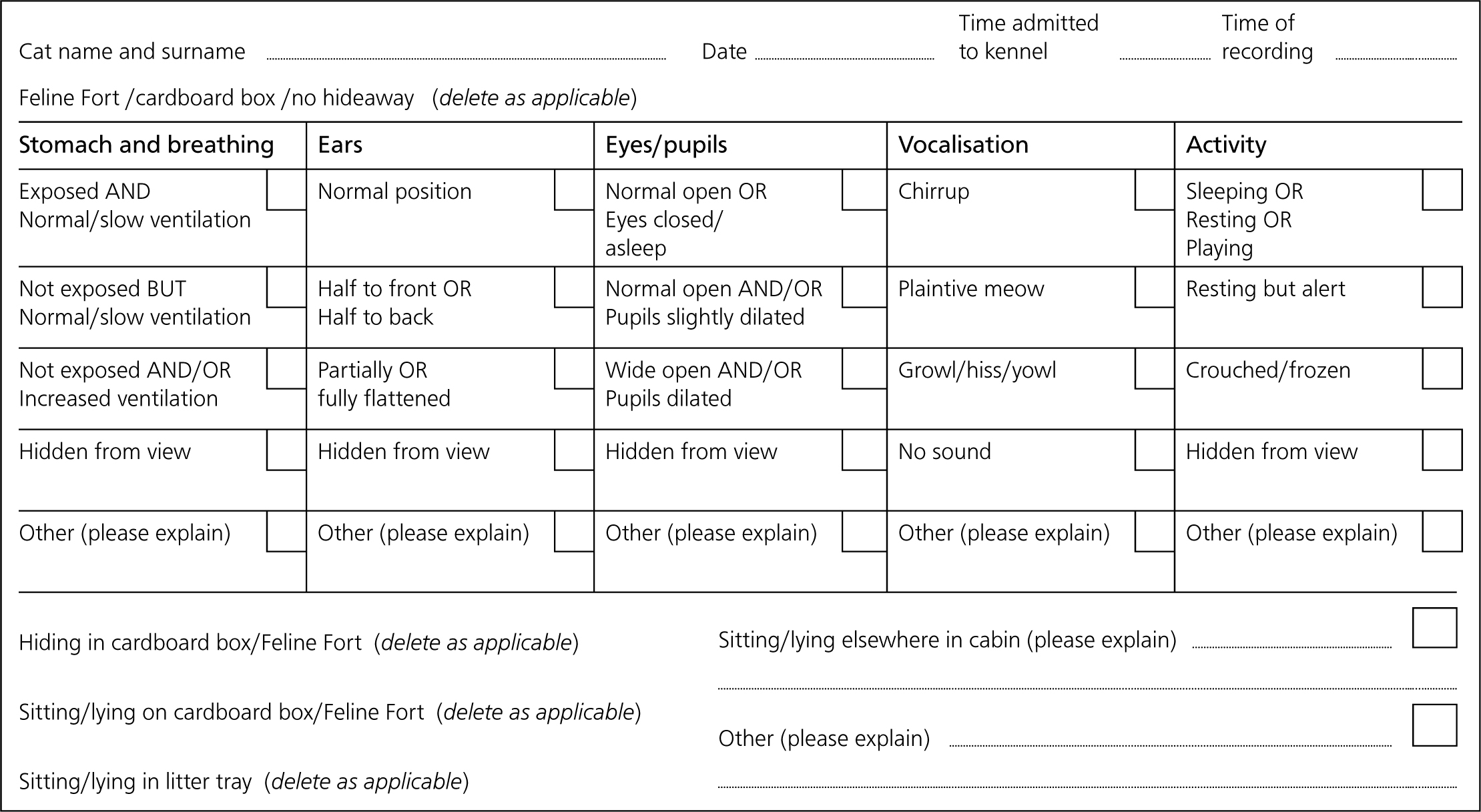

Prior to collecting any data, ethical consent to carry out the study was gained via Askham Bryan College ethics board, owners signed a consent form allowing their cats to take part in the study, an ethogram was compiled, and a simplified and adapted version of the Kessler and Turner, 1997 CSS was devised (Figure 2). No pilot study was undertaken.

On admission for routine surgery, cats were assessed by the veterinary surgeon and any cats that were unwell or injured were not able to participate in the study. In total, 21 cats were randomly recruited from a healthy population of cats admitted for routine surgery at a veterinary practice in Yorkshire. Age and gender are shown in Table 1; all cats were undergoing routine neutering operations. Distribution of surgery per group were as follows: cardboard box five castrates and two spays; Feline Fort three castrates and three spays; and the control group five castrates and three spays. Each cat was placed in the cattery which was separated away from other species and placed within a veterinary cat kennel (width 60 cm x depth 88 cm x height 64 cm) (Figure 3). The kennel had no access to an outside run and was provisioned with a vet bed, litter tray, water and food (after the procedure was performed) and then randomly allocated either the Feline Fort (n=6), cardboard box (n=7) or no hideaway at all (n=8), which was routine for the practice at the time and acted as a experimental control. The cardboard box was the same size as the Feline Fort. Bedding was also provided on and in the hideaways.

| Cat identification Number | Cardboard box (CB), Feline Fort (FF) or Control (C) | CSS | Sex | Age | Hiding or attempt to Hide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CB | 2 | M | 6M | Y |

| 2 | CB | 2 | M | 7M | |

| 3 | CB | 1 | M | 3Y | Y |

| 4 | CB | 2.5 | M | 5Y | |

| 5 | CB | 2 | F | 6M | |

| 6 | CB | 2 | M | 5M | |

| 7 | CB | 2 | F | 6M | |

| 8 | FF | 2 | M | 6M | |

| 9 | FF | 2 | M | 6M | |

| 10 | FF | 2 | F | 6M | |

| 11 | FF | 2 | F | 5M | Y |

| 12 | FF | 1 | F | 18Y | Y |

| 13 | FF | 2 | M | 4M | Y |

| 14 | C | 2 | M | 6M | |

| 15 | C | 1 | M | 6M | |

| 16 | C | 2 | F | 9Y | |

| 17 | C | 3 | M | 10Y | |

| 18 | C | 2 | M | 6M | |

| 19 | C | 1 | M | 6M | |

| 20 | C | 2 | F | 6M | |

| 21 | C | 2 | F | 6M |

CSS, cat stress score

After an acclimatisation period of 30 minutes the researcher entered the cattery and stood quietly for 1 minute not making visual or physical contact with the cat. Each cat was then scored on a simple tick sheet using five units of behaviour from the ethogram and the adapted simplified version of Kessler and Turner's 1997 CSS (Figure 4). The overall CSS for each cat was decided by determining which line on the tick sheet contained the most ticks. For example a cat with four ticks on the CSS line denoting ‘relaxed’ and one on the CSS line denoting ‘weakly stressed’, was coded as having a overall CSS of 1 (relaxed). Once the cat was discharged the Feline Fort was cleaned and stored ready for the next participant, a fresh cardboard box was used each time and bedding washed and dried.

The data collection took place over 2 months and was statistically analysed using the statistical software Minitab. The authors ran descriptive statistics, normal distribution was tested using Anderson-Darling test and the Levene's test checked for equal variance. As there were three groups, the data were ranked and were non-parametric, the Kruskal-Wallis test was selected to perform the statistical analysis (Martin and Bateson, 2007).

Results

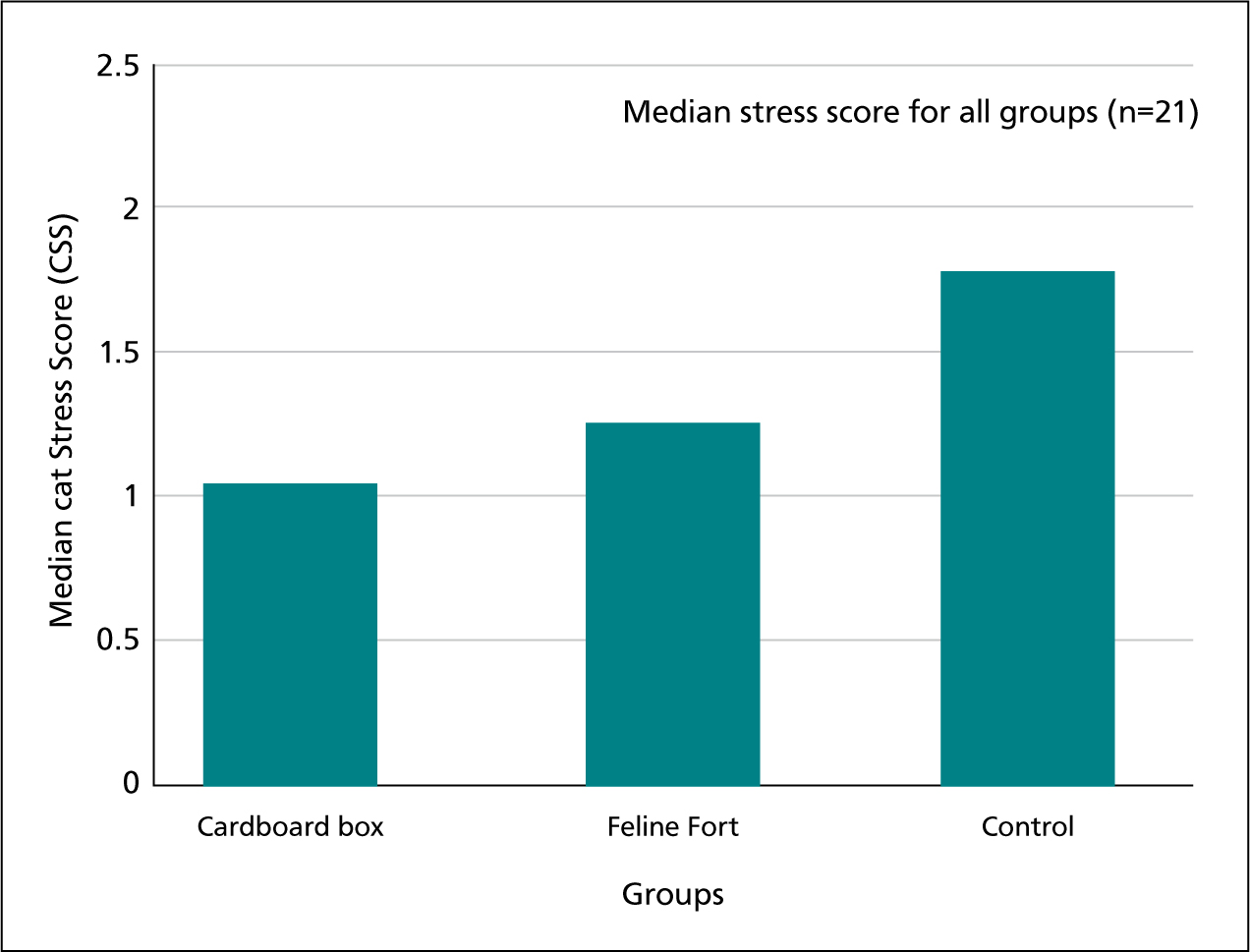

The CSS were rated as either 1 = relaxed, 2 = weakly stressed or 3 = very stressed. The median stress score for cats in all the groups was rated as 2 (Figure 5). Only five (38%) of the thirteen cats provided with a hideaway utilised the resource, however three (50%) of the six cats given the Feline Fort did utilise the hideaway. 16 out of 21 cats were aged less than 9 months (Table 1).

Descriptive statistics were obtained prior to statistical analysis using Minitab (Table 2). The Kruskal Wallis test showed that there was no significant difference in the CSS between the groups (Kruskal-Wallis test: H2 = 0.28, p=0.868), and therefore there was no statistical difference between the cats provided with a hideaway compared with the control group.

| Variable | Sample size (n) | SE Mean | StDev | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardboard Box | 7 | 0.170 | 0.450 | 2.00 |

| Feline Fort | 6 | 0.167 | 0.408 | 2.00 |

| Control | 8 | 0.227 | 0.641 | 2.00 |

Further analysis revealed that there was no statistical difference between males' CSS provided with hideaways compared with the control group (Kruskal-Wallis test: H2=0.26, p=0.878) or females (Kruskal-Wallis test: H2=1.67, p=0.435), or age (Kruskal-Wallis test: H2=3.57, p=0.168).

Discussion and limitations of the study

The results which revealed that there is no statistically significant difference in stress between cats provided with a hideaway, and the control group regardless of age or gender, are in direct contrast to findings by Godijn (2013) and Rehnberg et al (2015), and the researchers suggest that this may be due to sample size. A decision to restrict which cats participated in the study to those only admitted for routine procedures, and that were registered at only one veterinary practice, was an attempt to limit confounding variables, as an unwell cat would possibly have demonstrated an elevated CSS due to illness, and different environments could have also become a confounding factor. The convenience sample was not optimal in sampling terms (Denscombe, 2014). In order to attain a good probability in sampling, Denscombe (2014) suggested that for a population of 2530 (the number of cats registered at the veterinary practice) the total sample size to include all three groups should be between 278 to 357. In addition the small sample size could have resulted in a type II error where an expected significant result is not returned. Martin and Bateson (2007) suggested splitting the data into two equal halves and rerunning the test on each to determine if they are similar. However the sample size was too small to complete this task using Minitab.

While Kessler and Turner's (1997) CSS is comprehensive and used in a variety of other studies (Rochlitz et al, 1998; Gourkow and Fraser, 2006; Godijn, 2013; Kry and Casey, 2007; Moore and Bain, 2013; Vinke et al 2014; Rehnberg et al, 2015), the lead researcher decided to adapt and simplify it to allow for limitations in practice. On reflection, it became too simplistic, and some behaviour fell between two possibilities leaving some doubt as to which category to tick. A clearer picture could have been obtained by using the original options outlined by Kessler and Turner (1997). This would have created variety in the scores allowing for in-depth interpretation and a more powerful study, as accurate analysis is necessary for behaviour studies. Moore and Bain (2013) also adapted the Kessler and Turner (1997) CSS, and it is also interesting that they also reached the same conclusions within their sample.

In addition, the experiment did not take into account the possibility that the CSS of individual cats could change over time. Other researchers did consider this, and assessed cats provisioned with a hideaway over a longer time period (Godijn, 2013; Ellis et al, 2014). As the subjects were effectively day surgical patients this was not possible in the current study because it would have affected practice efficiency, however the researchers would suggest further studies assessing cats over a longer hospitalised stay, as CSS may have decreased for the cats over time, as well as determining if there is any variation in score over the course of day or longer hospitalised duration. Stella et al (2014) suggested that it can take up to 24 hours for cats to habituate to any change in environment, due to their lack of adaptability.

Other limitations included the observer present within the room when scoring the cat, rather than observing the cat through a window in a door (Figure 4). This could have influenced the CSS, as well as the hiding behaviour, of the cats that were naturally more nervous. The selection of cats could have also been more randomised by an independent person picking a number assigned to a group to which the cat would be allocated. In addition, on some days, the cats' behaviour could have been influenced by increased noise from dogs in the adjoining ward, pheromone therapy being switched on for other patients, and increasing the observation period prior to scoring the cat, in order to reduce the ‘Hawthorne effect’ (a process where a subject modifies their behaviour in response to taking part in a experiment or study). Inter-observer reliability was tackled with comprehensive training and an instruction sheet, however this did not encompass intra-observer checks.

One further complication was that the cats within both of the hideaway groups had to be placed in larger kennels in order to accommodate the size of the Feline Fort, or the same sized cardboard box, which were both too large (width 39 cm x depth 41 cm x height 30 cm) (Figure 4) for a standard sized (width 55 cm x depth 70 cm x height 55 cm) cat kennel at this veterinary practice, alongside alternative resting places, litter tray and food and water bowls. Due to the limited number of appropriate sized kennels, data were collected at two branch veterinary practices in order to maximise numbers, which affected cage position as well as the external environment; however, the observer was the same in each practice. Stella et al (2014) expanded on the theme of the importance of the environment; their research concluded that the macro environment (the environment immediately outside the kennel) is as important, and may be more so, as the micro environment (the environment within the kennel), and this provides an impetus for future research.

Conclusions and suggestions for future research

The results of this small scale study on the use of hideaways and, in particular the Feline Fort, should not be considered as conclusive as the evidence from studies carried out within rescue, adoption and quarantine centres does suggest that the use of hideaways is an important factor in allowing cats to perform natural behaviour, and adopt coping mechanisms while undergoing stressful events. However, this study could be used to remind nurses about the provision of hideaways as a method for reducing stress for their feline patients, and thus contribute to improving animal welfare of felines within the veterinary practice environment.

The study did highlight that although Cats Protection recommend the use of the Feline Fort within veterinary practices, the Feline Fort is too large to fit inside a standard sized cat kennel alongside alternative bedding, litter tray and food bowls. Therefore a cardboard box may be both a flexible and cheap alternative.

Future research suggests increasing the sample size and repeating the study using the Kessler and Turner (1997) CSS rather than a modified version. In addition, observing and recording cats over longer time periods may also provide additional information.

Increasing animal welfare and reducing animals' stress and discomfort is important to every veterinary nurse, and further research investigating the use of hideaways within veterinary practice is of benefit to increasing evidence-based nursing.