In all but very few cases a premedication is administered to the patient undergoing anaesthesia and it is vital that the veterinary nurse has a thorough understanding of the premedication protocol used. The premedication chosen will ultimately have effects on the anaesthesia and analgesia protocols used. The aims of premedication are to sedate the animal, produce anxiolysis, contribute to balanced anaesthesia, provide analgesia and help achieve a smooth and uneventful recovery (Kojima et al, 2002; Grant, 2006; Murrell, 2007). Inclusion of an analgesic drug contributes to pre-emptive analgesia. The prevention of pain is important as the veterinary profession has a moral, ethical and medical obligation to treat pain (Viñuela-Fernádez et al, 2007).

Acepromazine maleate (ACP) (Novartis Animal Health, Surrey, UK) is a phenothiazine and an α-antagonist (Murrell, 2007; Carroll, 2008). It is the most commonly used drug of this group for small animal premedication in the UK (Hall et al, 2001; Flaherty, 2003; Murrell, 2007; Posner and Burns, 2009) and produces mild to moderate sedation in dogs (Monteiro et al, 2009). The dose range for ACP is 0.01–0.05 mg/kg for dogs (Flaherty, 2003; Murrell, 2007) and it has been used to reduce anaesthetic induction agent requirements (Bufalari et al, 1997). At lower doses, tranquilization can be achieved and there are sedative effects at the higher doses. If tranquilization is not achieved at lower doses, increasing the dose will only contribute to intensifying adverse effects (Rock, 2007) and prolonging the duration of action (Murrell, 2007). ACP is protective against catecholamine-induced arrhythmias (Murrell, 2007) and has antiemetic effects (Flaherty, 2003).

Other beneficial effects include some degree of antihistamine and antispasmodic properties (Rock, 2007). However, the antihistamine properties of ACP are considered to be relatively weak (Flaherty, 2003). The adverse effects of ACP occur because of the drug's ability to antagonize α-receptors (Carroll, 2008); hypotension is a common adverse effect because ACP antagonizes the α-receptors found on the smooth muscle cells of peripheral blood vessels (Bill, 2006). This reduces the animal's ability to vasoconstrict, also causing hypothermia (Rock, 2007). ACP has mental calming effects (Rock, 2007), helping to produce anxiolysis and sedation, which contribute to the aims of premedication. As with most other phenothiazines, the drug has no significant analgesic properties (Hall et al, 2001; Murrel, 2007).

Butorphanol (Torbugesic®, Pfizier Animal Health, Kent) is included in the opioid group of drugs and is a K-opiate receptor agonist (Caulkett et al, 2003; Kukanich and Papich, 2009). Butorphanol has analgesic properties due to the activation of K-receptors (Monteiro et al, 2009) and is commonly used for intra- and post-operative analgesia. However, it is important to appreciate that sedation, unlike analgesia, can be achieved at lower doses (Kukanich and Papich, 2009). In dogs, the drug is recognized for its analgesic and antitussive properties (Hall et al, 2001; Lamont and Mathews, 2007), making it a useful component of a premedication protocol. Butorphanol appears to be a popular choice for inclusion in a premedication protocol and is considered safe and effective (Fox et al, 2000). The drug is effective against mild to moderate pain and is one of the most popular choices for analgesia and anaesthesia purposes (Kukanich and Papich, 2009). The dose range for butorphanol is 0.1–0.4 mg/kg for dogs (Lamont and Mathews, 2007). There are minimal cardiovascular effects and relatively less respiratory depression associated with the use of butorphanol (Bill, 2006, Kukanich and Papich 2009), but potential adverse effects include decreased gastrointestinal mobility and constipation (Kukanich and Papich, 2009).

The addition of butorphanol to an ACP premedication produces a neuroleptanalgesic (Bufalari et al, 1997). This combination has been found to have only mild effects on the cardiorespiratory system and be capable of inducing relatively deep sedation in dogs, but appears to have no analgesic effects and a poor ability to reduce reactions to external stimuli in dogs (Kojima et al, 1999). It is therefore appropriate to administer pre-emptive analgesia when using this combination. Carprofen (Rimadyl®, Pfizier Animal Health, Kent) is indicated for post-operative analgesia in dogs following soft tissue and orthopaedic surgery (National Office of Animal Health, 2010a) and has been shown to be effective in reducing postoperative pain when given pre-emptively (Welsh et al, 1997; Larendo et al, 2004)

The objectives of this study were to compare the use of ACP and ACP-butorphanol premedication combinations, both with carprofen administration, in bitches undergoing elective ovariohysterectomy, focussing on volume of propofol (Rapinovet®, Intervet/Schering Plough Animal Health, Milton Keynes) required to induce anaesthesia, post-operative pain, quality of recovery and the owner's opinion of the bitch post operatively. For ethical clarification, the veterinary surgeons who participated in this study were not asked to modify their chosen protocol for research purposes; one veterinary surgeon preferred to use an ACP premedication whereas the other preferred to combine ACP with butorphanol.

Method

The study was completed at one veterinary practice and involved 20 healthy bitches of a variety of breeds ranging from 6 months to 7 years of age. The weight range of the bitches was 5–38 kg. The bitches were admitted for a routine, elective ovariohysterectomy and were therefore not anaesthetized purely for research purposes. After obtaining informed consent for the procedure and participation in the study from the owners, bitches were settled in a suitably sized kennel with a Vetbed. There was minimal handling to reduce excitement. This study was completed over a period of time according to when suitable patients were admitted, but the same kennel area was used for each patient. Noise was consistently kept to a minimum and the area was maintained at 16–18 °C.

One veterinary surgeon completed ten procedures using an ACP (2 mg/ml) premedication with carprofen (50 mg/ml), while the other veterinary surgeon completed ten procedures using an ACP (2 mg/ml) and butorphanol (10 mg/ml) premedication with carprofen. The dose rate used for ACP only was 0.04 mg/kg. When butorphanol was added to the ACP premedication, both drugs were given at the dose rate of 0.01 mg/kg in one syringe, as decided by the veterinary surgeon. The dose rate used for carprofen was 4 mg/kg. All drugs were administered subcutaneously. Premedication administration was recorded appropriately.

Anaesthesia was induced with propofol (10 mg/ml), 30 minutes post premedication administration, into the cephalic vein in all bitches according to the dose rate of 4 mg/kg. The veterinary surgeon administered the propofol to effect until the bitch reached stage III, plane I of anaesthesia. Administering the induction agent to effect indicated whether the requirement was reduced as a result of the premedication. The volume of propofol administered was recorded appropriately. Oxygen was administered and isoflurane (Isoflo®, Abbott Laboratories, Berkshire) was used to maintain anaesthesia at stage III, plane II in all bitches. Anaesthetic circuits used were the circle, parallel lack and Ayres T-piece.

The ovariohysterectomy was performed when all bitches were in stage III, plane II of anaesthesia and this plane was maintained throughout the procedure. Maintenance of anaesthesia with isoflurane was stopped as the last suture was being placed by the veterinary surgeon and the bitch was given 100% oxygen, according to practice protocol. Theatre temperature was maintained between 21–23 °C. The time of stopping the delivery of isoflurane and extubation was recorded. After extubation, bitches were returned to the kennel and kept warm with a Vetbed, blankets and heat pads.

There was minimal contact with all bitches during recovery, but all were closely observed. The time of sternal recumbency and standing was recorded. Assessment of pain began from the time of sternal recumbency and then hourly until the time of discharge; four assessments of pain were made in each bitch by one veterinary nurse. Assessment was completed by observation and then by approaching the bitches slowly and gently. A simple descriptive pain scoring system was used (Table 1).

| Pain score | Signs | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | No pain, no overt signs of discomfort, no resentment to firm pressure | |

| 1 | Some pain, no overt signs of discomfort, resentment to firm pressure | |

| 2 | Moderate pain, some overt signs of discomfort, made worse by firm pressure | |

| 3 | Severe pain, overt signs of persistent discomfort, made worse by firm pressure. Signs of pain include: | |

| Hyperalgesia or allodynia | ||

| Hunching, praying position, not normal resting position | ||

| Stiffness, no weightbearing on affected limbs | ||

| Vocalization: barking, growling, whining | ||

| Changes in facial expressions | ||

| Guarding affected area or paying attention to affected area | ||

| Aggression | ||

| Weak tail wag | ||

Adapted from: Waterman-Pearson (1999) The BSAVA Manual of Small Animal Anaesthesia and Analgesia, edited by Chris Seymour and Robin Gleed. Price and Nolan (2007) The BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 2nd edition, edited by Chris Seymour and Tanya Duke-Novakovski. Reproduced with permission from BSAVA Publications.

The following day immediately after discharge, each owner completed a questionnaire consisting of six questions to assess the bitch's demeanour after the procedure. A rating system of 1–3 (with 3 being the highest) was used to assess how normal each bitch's eating, drinking and sleeping habits were, how bright the bitch was, how much attention was paid to the surgical wound and how much pain the owner considered the dog to be in. Owners were supplied with a copy of the pain score used and this was thoroughly explained to them. Owners were telephoned 24 hours after the bitch was discharged for their scores.

Statistical analyses of the results include T-test, repeated Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Mann-Whitney U test. In all tests p≤0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Results

Effect of the two premedication combinations on propofol requirements

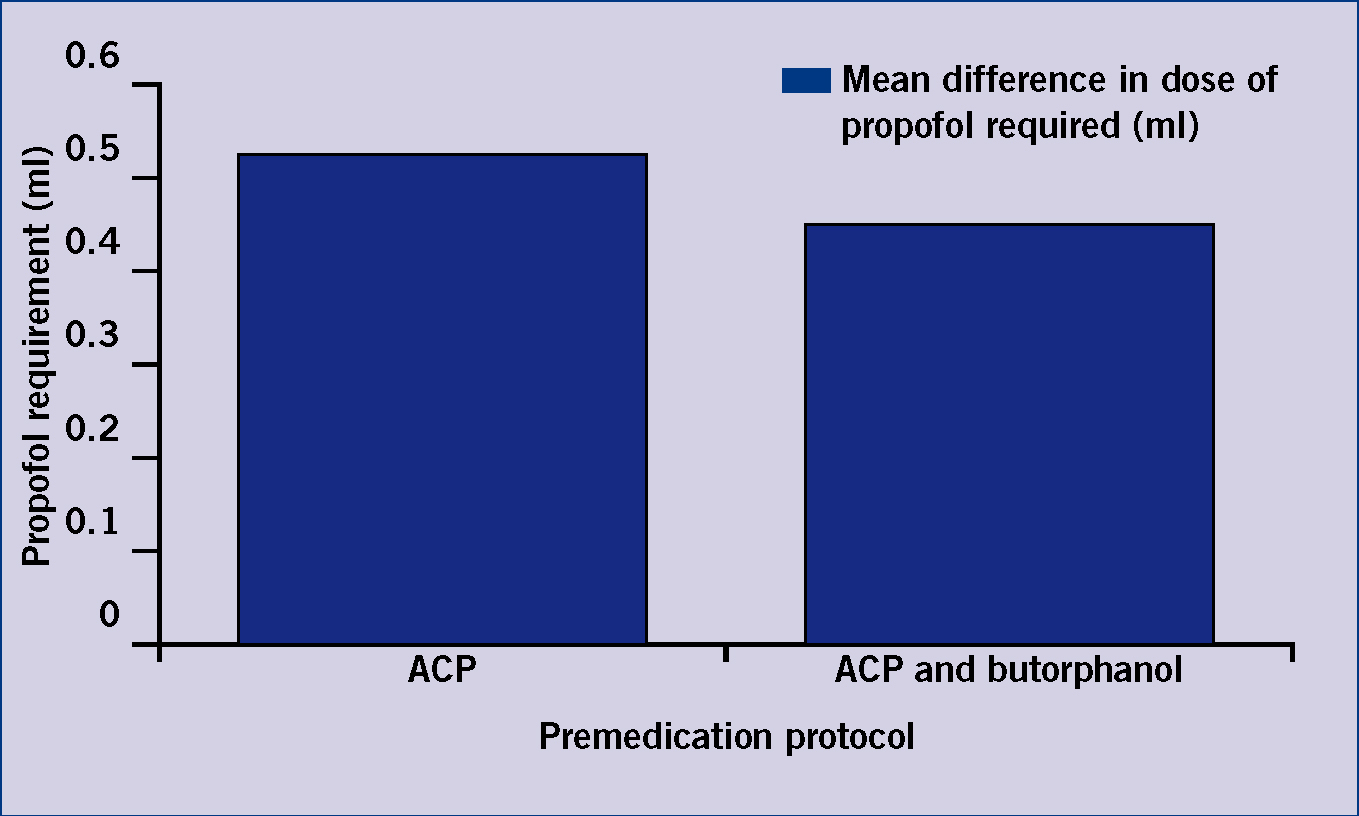

Those bitches premedicated with a combination of ACP and butorphanol had a lower propofol requirement to induce anaesthesia. However, T-test revealed that there was no significant (p=o.844) difference between the propofol requirement when using the two premedication combinations (Table 2; Figure 1).

| Premedication protocol | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ACP (+/- S.D) | ACP and butorphanol (+/- S.D) | P value | |

| Mean difference in dose of propofol required (ml) | 0.53 (+/- 1.347) | 0.424 (+/- 0.997) | 0.844 |

Effect on the post-operative pain score assessment

Adding butorphanol to an ACP premedicant was not shown to have any statistically significant effect on the immediate, 1 hour, 2 hour, 3 hour and 24 hour post-operative pain score (all p>0.05) (Table 3).

| Time(hours) | Treatment | Median | Quartile ranges | U value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ACP* | 0 | 0–1.0 | 35.0 | 0.303 |

| ACP + butorphanol | 0 | 0–0 | |||

| 1 | ACP* | 0.5 | 1.0–1.0 | 30.0 | 0.141 |

| ACP + butorphanol | 0 | 0–0 | |||

| 2 | ACP* | 0 | 0–1.0 | 45.0 | 1.0 |

| ACP + butorphanol | 0 | 0–0 | |||

| 3 | ACP* | 0 | 0–1.0 | 45.0 | 1.0 |

| ACP + butorphanol | 0 | 0–0 | |||

| 24 (completed by owner) | ACP* | 1 | 1.0–2.0 | 34.5 | 0.296 |

| ACP + butorphanol | 1 | 0–1.0 |

Effect of recovery time

ANOVA testing showed that adding butorphanol to an ACP premedication significantly increased the time taken for the bitches to regain sternal recumbency (p=0.017) on average by 14.6 minutes. The addition of butorphanol also significantly increased the time taken for the bitches to stand (p=0.017) on average by 38.1 minutes. The average time taken for extubation was the same for both combinations used. There is a significant effect on the three time points of recovery (p<0.001). The relationship between the premedication combination used and the time taken for recovery is approaching statistical significance (p=0.056) (Table 4).

| Time (Average period of recovery in minutes) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Extubation (+/− S.D) | Sternal recumbency (+/− S.D) | Standing (+/− S.D) |

| ACP | 6.8 (+/− 3.259) | 18.2 (+/− 5.69) | 57.6 (+/− 27.94) |

| ACP + butorphanol | 6.8 (+/− 2.616) | 32.8 (+/− 13.81) | 95.7 (+/− 46.42) |

| Treatment SED = 6.69 p=0.017 | Time SED = 6.77 p=<0.001 | ||

Treatment x time = 10.29; p=0.056

SED, standard error of difference

Owner questionnaire

Although bitches administered an ACP premedication appeared brighter and were perceived as having better drinking, eating and sleeping patterns, they also paid the most attention to the wound. However, these findings were insignificant as indicated by the p values.

Discussion

The results of this study could prompt practices to assess their current premedication protocol to ensure that they are using a premedication protocol that provides maximum benefit to the patient, especially post operatively. Appreciation of pain in both the veterinary profession and among the general public is increasing (Raekallio et al, 2003), so it is important to assure owners that all measures have been taken to keep their animal as comfortable as possible.

There was no statistically significant difference between the volume of propofol required to induce anaesthesia between the two groups, although those bitches premedicated with ACP only, did have a marginally higher average requirement. Bufalari et al (1997) found that dogs premedicated with either ACP or butorphanol only, had a propofol requirement of 4.4 mg/kg to induce anaesthesia, whereas where an ACP and butorphanol combination was used, there was a requirement of 3.3 mg/kg. These findings support that dogs administered a combination of ACP and butorphanol have a slightly lower induction agent requirement.

This study found no statistically significant difference between the pain scores of those dogs administered the two premedication combinations, although those bitches administered an ACP only premedication did have higher pain scores, suggesting they experienced more post-operative pain. Although the analgesic properties of butorphanol have been regarded as being poor (Kojima et al, 1999; Murrell, 2007), the drug is recognized for providing suitable analgesia when combined with ACP at a dose rate of 0.2–0.3 mg/kg (National Office of Animal Health, 2010b). The pain scoring system provides a relatively subjective method of assessing pain but is easily completed in practice. However, Coleman and Slingsby (2004) found that from a sample of 541 veterinary nurses, only 8.1% used formal pain scores with the simple descriptive scale, such as the one used in this study, being the most common. This suggests that pain scoring needs to be used more in practice to assess the pain state of animals post operatively, and is an area in which veterinary nurses can take responsibility.

Adding butorphanol to an ACP premedication significantly increased the average time taken for the bitches to reach sternal recumbency and be able to stand, although there was no difference on the average time for extubation between the two groups. It has previously been found that an ACP and butorphanol premedication combination administered intramuscularly significantly increases the time taken for extubation and sternal recumbency to be regained after propofol-induced anaesthesia, maintained with isoflurane (Smith et al, 1993). Although this study found a difference in the time taken for sternal recumbency to be regained, there was no effect on the time taken for extubation to be completed. Bufalari et al (1997) completed a study without the use of a volatile maintenance agent and also found that a combination of ACP and butorphanol led to significantly longer recoveries after propofol administration than when each drug was used separately. When used separately, an ACP only premedication led to the quickest recovery time (Bulfalari et al, 1997). The addition of butorphanol to an ACP premedication appears to be the causative factor for increasing recovery times.

| Characteristic | Treatment | Median | Quartile ranges | U value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brightness | ACP* | 2.0 | 3.0–2.0 | 27.0 | 0.091 |

| ACP + butorphanol | 1.0 | 1.0–2.0 | |||

| Drinking | ACP* | 1.0 | 1.0–2.0 | 36.0 | 0.283 |

| ACP + butorphanol | 1.0 | 1.0–2.0 | |||

| Eating | ACP* | 0 | 0.0–2.0 | 42.5 | 0.554 |

| ACP + butorphanol | 0 | 0.0–1.0 | |||

| Sleeping | ACP* | 3.0 | 3.0–3.0 | 48.0 | 1.0 |

| ACP + butorphanol | 3.0 | 2.0–3.0 | |||

| Attention to wound | ACP* | 1.0 | 0.0–1.0 | 45.0 | 0.741 |

| ACP + butorphanol | 0.5 | 0.0–1.0 |

Although the results for the post-operative questionnaire were statistically insignificant, bitches administered an ACP only premedication appeared brighter and were considered as having better drinking, eating and sleeping patterns, but they also appeared to pay the most attention to the wound. This may be because adding butorphanol to an ACP premedication has been found to lengthen the recovery period (Smith et al, 1993) and bitches administered an ACP only premedication may have recovered more quickly.

It is important to differentiate between statistical significance and clinical significance. Although some results were insignificant, if the practice was to consistently find that bitches administered an ACP only premedication tended to be in more post-operative pain than those administered a premedication combination, this should influence the reassessment of the protocol being used.

Limitations of the study

The participation of two veterinary surgeons in this study may have affected the results. However, for ethical reasons, it was necessary for two veterinary surgeons to participate to prevent the requirement for the premedication protocols being modified for research purposes.

Two different dose rates of ACP were used in the ACP only premedication (0.04 mg/kg) and the ACP and butorphanol premedication (0.01 mg/kg). This different dose may have affected the results but it should be appreciated that this was the veterinary surgeon's clinical decision. If the dose rate of ACP was changed to be the same in each premedication, this would constitute modifying treatments for research purposes.

Owners scored the bitches' brightness, drinking, pain, eating and sleeping patterns post operatively after 24 hours. Although the pain scoring system was explained to the owners, ideally one person would have scored all of the bitches to reduce differences in pain perceptions. Bitches were not returned to the practice after 24 hours to be pain scored by a veterinary nurse as it was felt that this could cause them further stress and would have affected the pain scores.

To add more value to the pain scoring assessment, other more objective parameters that could have been measured to provide an indicator of pain experienced include heart rate and blood pressure, although the provision of the necessary equipment would be essential. Nurses wishing to assess pain in their patients should make use of both objective and subjective measurements of pain to provide a more complete picture of the animal's condition.

It is appreciated that this study used a relatively small sample size and this is likely to have affected the statistical analyses; a larger sample size may have confirmed significance in some tests, especially where results were approaching significance. This study was completed as a final year dissertation and so was constrained by time and facilities. Ideally an improved study would be one taking place at one practice, involving two veterinary surgeons and with the same nurse pain scoring the patients; a larger sample size would be gained from carrying out the study over a longer period of time.

Recommendations for further research

There appears to be conflicting evidence regarding the analgesic properties of butorphanol when used in a premedication protocol. Further research is therefore required in this area to determine the usefulness of this opioid for premedicating animals for surgery.

Investigating the effects that different routes of administration have on the criteria used in this research could alter the way in which premedications are administered to patients. It may be possible that although a subcutaneously administered premedication takes longer to show sedative effects, there could be prolonged analgesic effects. Essentially, further research in this area will further enhance the profession's understanding and appreciation of different premedications, ultimately improving the care that patients receive.

Conclusions

Adding butorphanol to an ACP premedication significantly increases the length of time taken for the bitch to reach sternal recumbency and stand. No statistically significant effects of adding butorphanol to an ACP premedication were found in the volume of propofol required to induce anaesthesia, time of extubation, pain score or behaviour 24 hours post operatively between the two groups.