In recent years, rehoming shelters have experienced a high turnover of cats requiring aid in finding a new home, with the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) taking in 29 432 individuals and The Cats Protection sheltering 41 000 in 2019 alone (RSPCA, 2020; Cats Protection, 2020).

Chronic exposure to stress can result in behavioural and physiological changes, which can be viewed as undesirable in prospective adopters (Stella and Croney, 2016). Stress can reduce an individual's food and water intake, as well as decreasing grooming time and activity levels (Stella et al, 2013). Inappropriate elimination can be seen through urine and faecal marking as a means of coping with a new environment through the reassurance of familiar scents (Heath, 2007) or can be the result of feline interstitial cystitis, a chronic pain syndrome often triggered by stressors (Stella et al, 2013).

With mounting concern around animal welfare, natural-based phytotherapeutic interventions have grown in popularity for veterinary professionals, animal carers and pet owners alike. One such product is Pet Remedy (Unex Designs), a valerian-based calming product that can be purchased in sprays, wipes and diffusers.

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is an inhibitory neurotransmitter used in the regulation of neuron excitatory signalling in the mammalian nervous system (Phulera et al, 2018). GABA elicits change by reducing the activity of neurons and signal transduction. Upon attachment to a GABA receptor, the neurotransmitter produces a biological calming effect, and is found to operate in over one third of neurons (Roy-Byrne, 2005). The primary ingredient of Pet Remedy is valerian oil (Pet Remedy, 2021). Derived from a medicinal herb capable of producing anxiolytic and sedative effects, valerian oil mimics GABA neurotransmitters to activate the pathway and trigger GABA receptors (Yuan et al, 2004). Studies into the efficacy of valerian have found it to be effective in a range of species including – but not limited to – cats, rats, birds and humans (Yuan et al, 2004; Skomorucha and Sosnówka-Czajka, 2018).

This study aims to investigate Pet Remedy's ability to reduce feline stress-related behaviours in a rehoming shelter.

Review of literature

Pet Remedy

Cats

Available studies have suggested that cats react positively to Pet Remedy. When used during veterinary check-ups, where Pet Remedy wipes were compared to placebo, veterinary professionals indicated positive responses to Pet Remedy, with the majority of those treated with the product being reported as ‘relaxed’ (Unpublished data). This study was designed to be blind; however, Pet Remedy is known to have a distinctive smell – especially against the placebo, deionised water. Bias may be present as the veterinary professional had to complete a questionnaire upon completion of the consultation.

Hale and Roscini (2021) appraised recordings of felines and scored them according to the cat stress score (Kessler and Turner, 1997), allowing for a blind stress appraisal as examiners were not present at the time of testing. Results showed that 75% of cats exposed to the placebo were regarded as ‘very fearful’ or ‘terrified’, while this value decreased to 25% in those exposed to Pet Remedy. However, as it was recordings which were appraised, there was no way to tell if cats had any health conditions which may affect stress scorings: a high likelihood as recordings were acquired from a clinical setting. Over and above this, there was no way to appraise the cats’ own temperament and baseline before consultation.

Dogs

Taylor and Madden (2016) appraised canine behaviour – and duration of said behaviour – by exposing dogs who had a history of stress and anxiety to Pet Remedy in a novel environment. There was no significant difference found in duration of observed behaviours, nor in frequency of behaviour expressions, suggesting Pet Remedy does not reduce stress in canines with a history of anxiety. However, this study does lack detail with regards to dog handling prior to testing, and has not reported whether any participants were taking medication at the time which may have affected their stress levels.

Anxiety-related behaviours were appraised by 28 participating owners using a questionnaire, completed 30 days after installing Pet Remedy diffusers in the home (Lloyd et al, 2019). In total, 43% of owners reported an improvement in their dogs' stress-related behaviours; this value was found to be insignificant, though further research would benefit from a larger sample size as well as the use of a blind-study with placebo to ensure no bias from owner appraisal.

Rabbits

A double-blind, placebo-controlled set-up was used to assess the efficacy of Pet Remedy in reducing fear-related behaviours exhibited during handling of domesticated rabbits (Unwin et al, 2019). During handling, rabbits exposed to Pet Remedy recorded significantly lower heart rates than those in the placebo group. Furthermore, a significant increase in behaviours regarded as ‘positive’ was observed, suggesting Pet Remedy may have an effect in reducing fearful behaviours in rabbits.

Methods and materials

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee at Scotland's Rural College.

Participants

To meet testing criteria, participants (n=46) had to be at least 1 year old and housed individually in their respective kennels. Cats with pre-existing illnesses that could be exacerbated by stress (for example heart disease, renal disease) were excluded. Cats took part in the study once they had been in the kennel for at least 24 hours to acclimate, as suggested in the method used by Kry and Casey (unpublished data).

Cats were sourced from three locations: four (8.7%) from a rescue centre in Dunfermline, 12 (26.1%) from a centre in Cleish and 30 (65.2%) from a centre in Kinross.

Experimental design

This study took place across three cat shelters and collected quantitative data on stress-related behaviours from cats. Independent measures were utilised using a double-blind, placebo-controlled methodology. Participants could be randomly assigned to one of three groups:

- Control

- Treatment 1 (T1)

- or Treatment 2 (T2).

The cat stress score (Kessler and Turner, 1997) was used to appraise feline behaviour and produce a subsequent stress score out of 77, and respiration rate (RR) was recorded. Pet Remedy and deionised water were set-up by a third party, prepared into identical spray bottles and randomly labelled ‘T1’ or ‘T2’. The examiner was not aware which treatment was which: during all testing the examiner wore a nasal scent blocker and a mask with one drop of Olbas Oil (G.R. Lane Health Products Ltd.) to ensure no distinctive scent could be detected. All scoring took place from outside the kennel to limit stress to participants caused by the examiner's presence. Only one examiner was used in data collection to ensure consistency between scoring-based data.

Participants were assessed to produce a pre-treatment cat stress score and respiration rate: after which, treatment was applied during delivery of the evening meal and a post-treatment cat stress score and respiration rate taken 30 minutes later. One full spray of a treatment was applied to a woven-gauze swab outside of the kennel before being placed within 30 cm of the participant in the kennel. The swab remained in the kennel for 30 minutes before post-treatment readings were taken (Graham et al, 2005; Hermiston et al, 2018). Swabs were removed once all scoring was complete.

On the initial visit to each cattery, control measures were taken: no product was applied, participant respiration rate and cat stress score were recorded and food was given. Respiration rate and cat stress score were recorded 30 minutes later.

The order of treatments in the centre in Cleish were as follows: control, treatment 1, treatment 2. The order of treatments at the centre in Kinross were as follows: control, treatment 2, treatment 1. The centre in Dunfermline only received control assessment due to lack of participants. Only one treatment was to be used per day of scoring, with a wash-out period of 5 days between treatments to ensure no interference between products. All eligible participants present at time of testing were included, including those previously exposed to other treatments.

Testing protocol

Participants were tested at approximately the same time of day between each shelter, with all treatments applied upon delivery of the evening meal. It was decided that if a participant showed extreme negative behaviours (for example, mouth breathing or lunging at the examiner) then the test would be stopped and the participant removed from the study.

Physiological measures

Respiration rate was taken visually by the examiner. Each kennel door had a mesh window which allowed the examiner to view from a distance without having to enter the kennel. The number of breaths was counted over 15 seconds, and then converted into breaths per minute.

Stress scoring

Stress levels were evaluated using the seven-level cat stress score (Kessler and Turner, 1997). This system details eleven aspects of feline body language and has the examiner apply a numerical score ranging from 1 (fully relaxed) to 7 (terrified), after which all eleven scores were added together to produce an overall score out of 77. All scoring was completed by the same examiner to ensure consistency between the produced scores.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance and post-hoc Tukey

Statistical analysis was performed using Minitab (Minitab LLC), and a confidence level of 95% used. The differences between pre- and post-treatments for respiration rate and cat stress score were each analysed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate whether there was statistical significance between the scores of either of the groups. The ANOVA results were then analysed using a post-hoc Tukey honest significant difference test to determine where exactly the statistical significance lay.

Results

To test the hypothesis of whether Pet Remedy has an effect on stress-related behaviours in cats in a rehoming shelter, the relevant collected data were collated before pre- and post-treatment differences for respiratory rate and cat stress score were calculated and then analysed.

Participants

Of all the cats participating in this study (n=46), 32.6% (n=15) were exposed to Pet Remedy, 37% (n=17) to deionised water and 30.4 % (n=14) to neither treatment. British Shorthairs (BSH) represented 4.4% (n= 2) of the population, with 60.7% (n=28) being Domestic Shorthairs (DSH) and the remaining 34.8% (n=16) being Domestic Longhairs (DLH). With regards to sex, 67.4% (n=31) were female and 32.6% (n=15) male. Age of subjects ranged from 1–12 years old with a mean age of 4.8 years, and all testing took place from November 2021 to February 2022.

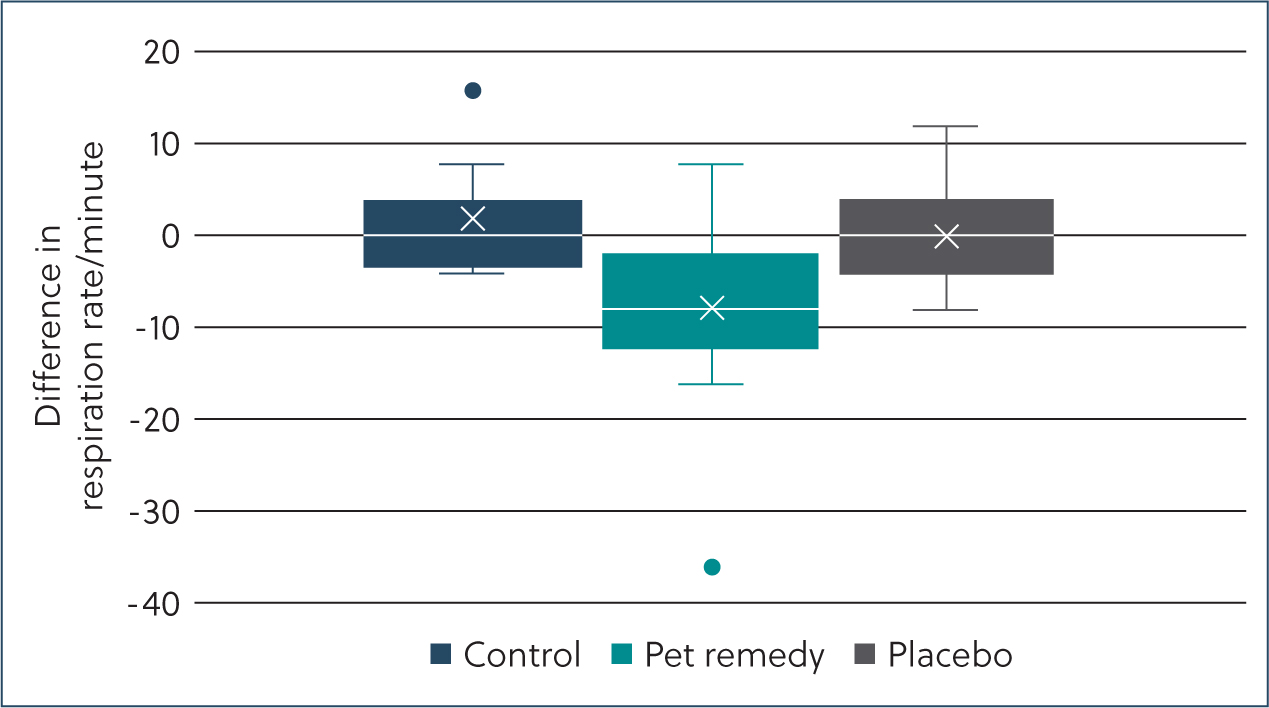

Analysis of effect on respiration

The ANOVA showed that there were statistically significant differences between mean difference in respiration rates of at least two groups (F2, 43=8.47, P=0.001) (Figure 1).

Tukey's honest significant difference test for multiple comparisons found that the mean difference in respiration rate for participants treated with Pet Remedy (M= –8, ±10.01) was significantly lower than the control group (P=0.003, 95 % C.I. =[–7.89, 4.94]) and the placebo group (P=0.008, 95 % C.I. = [–14.53, –1.94]). There was no significant difference between the control group (mean = 1.71, +/– 5.39) and the placebo (M=0.26, ±4.85)(P=0.842).

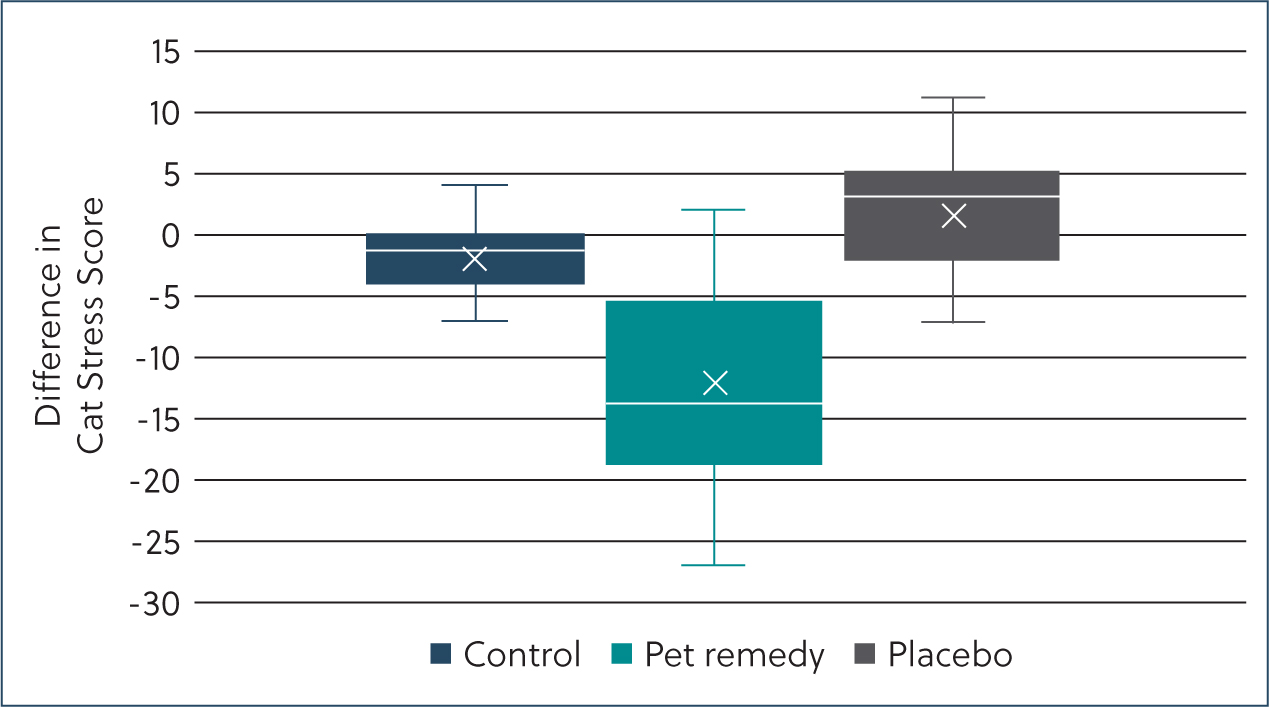

Analysis of effect on stress score

The ANOVA showed that there were statistically significant differences between mean difference in stress score of at least two groups (F2, 43=21.47, P=0.000) (Figure 2).

Tukey's honest significant difference test for multiple comparisons found that the mean value of difference in CSS for participants treated with Pet Remedy (M= –11.53, ±7.86) was significantly lower than the control group (P=0.000, 95 % C.I. = [–15.04, –4.60]) and the placebo group (P=0.000, 95 % C.I. = [–18.04, –8.09]). There was no significant difference between the control group (mean= –1.71, ±2.94) and the placebo (M=1.53, ±4.83) (P=0.278).

Discussion

Due to the production of significant results with regards to differences in cat stress score and respiration rate, it can be accepted that Pet Remedy can reduce the incidence of feline stress-related behaviours in a rehoming shelter. Results from prior clinical trials support this finding (Unwin et al, 2019; Hale and Roscini, 2021) – particularly with Unwin et al (2019) who found an association between Pet Remedy and reduced heart rate, as this study found in relation to respiratory rate.

The Kessler and Turner (1997) cat stress score allowed for an in-depth analysis of stress, through developing a system allowing animal stress to be scored out of a total of 77. While Hale and Roscini (2021) measured stress on a simplified scale of 1–7, scoring out of 77 allowed for improved accuracy when determining stress level. Using the more detailed scoring method allowed appraisal of subtler changes in stress being experienced, whose reductions may have previously been overlooked and the effect of Pet Remedy not recognised.

Project limitations

Respiration rates were recorded by counting over a period of 15 seconds, then multiplying this counted value by four to produce a respiration rate/min. This method has been criticised previously for possible inaccuracies when compared to counts conducted over 30 and 60 seconds (Kallioinen et al, 2021). It has been found that respiration rates are most accurate when the participant is unaware of the measurement or presence of the examiner (Kallioinen et al, 2021), therefore it would be beneficial to minimise the examiner's physical presence, such as with Hale and Roscini (2021) use of video recordings.

This study collected data from 46 participants, with 95.4% presenting as either Domestic Long or Short Hair. An increased sample size would be beneficial to improve understanding of the effect of Pet Remedy on the species as a whole and not a particular breed subset.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that Pet Remedy can reduce the incidence of feline stress-related behaviours in a rehoming shelter. The produced mean cat stress score and respiraton rate differences between the placebo and control groups provide reliability to these findings as they were too similar to be regarded as significant. Meanwhile, Pet Remedy produced a significant reduction when compared against both alternative treatments.

The findings of this study suggest that Pet Remedy may have the potential to improve stress and anxiety experienced by cats in rescue shelters. This is especially important for the improvement of welfare standards and, in turn, mental and physical health status which can negatively impact quality of life.