MacLennan (2017) suggested that directing people to ‘do’ has always produced inferior results compared with inspiring people to ‘want to’ do. Mentoring and coaching, if provided skilfully, inspire people to ‘want to’ — but what exactly are these techniques, and how can they be used by members of the veterinary practice team?

Mentoring

Mentoring usually involves a more experienced practitioner (mentor) who serves as a role model in support of a more junior member of staff (mentee) in an area or technique. Mentoring within health care often involves students on placement being supported by a mentor whom they can shadow to see how theory and practice are integrated (Quinn et al, 2014). This relationship is firmly one in which the mentor is more of technical expert, which enables them to share their valuable knowledge and experience. Traditionally, mentoring is the long-term passing on of support, guidance and advice, with a focus on nurturing and guiding the learner (Sibson, 2011). Mentoring is generally understood as a special kind of relationship where objectivity, credibility, honesty, trustworthiness and confidentiality are critical (Connor and Pokora, 2012). While some coaching skills may be used as a mentor, one does not need to be a mentor to be a coach (Donner and Wheeler, 2009).

Coaching

Coaching is a collaborative relationship between a coach and a willing individual — the coachee (Donner and Wheeler, 2009). It is usually a time-limited strategy used to help a person to identify and understand any issues and areas of desired change, and then assist them to use their beliefs, skills and resources to achieve their own success (Quinn et al, 2014). Success is the principle from which a coach should operate, with the coachee finding the solutions, implementing them, and thus succeeding. Coaching is not about giving answers — it is about helping coaches to identify the right questions, and then empowering coachees to find their own answers. Donner and Wheeler (2009) described coaching as a collaboration in which the coach acts like a midwife; supporting, encouraging and helping the coachee through the experience, while acknowledging the coachee as the expert and the person ‘making it happen’.

Coaching vs. mentoring

Often the terms mentoring and coaching are used interchangeably — but mentoring is not the same as coaching. Both are independent, but related by the communication strategies that are often used to promote professional development and facilitate retention (Donner and Wheeler, 2009). Box 1 and Table 1 illustrate the similarities and differences between coaching and mentoring.

| A coach… | A mentor… |

|---|---|

| Creates space to think | Advises and suggests |

| Is non-judgemental | May need to make judgements |

| Gives ownership | Leads by example |

| Challenges | Helps to develop |

| Need not be an expert | Is usually more experienced |

| Stands back | Stands close |

| Gives responsibility back | Can feel responsible |

| Challenges beliefs, thoughts and behaviour | Shares knowledge and experience |

| Asks ‘What decision?’ | Guides to a decision |

| Works within a set time frame | May work over a long period |

| Focuses on specific developmental areas | Takes a broader view |

Donner and Wheeler (2009) suggested that understanding their differences will help individuals and organisations ensure they choose the right strategy for the right purpose. While the two strategies are not interchangeable, it is likely that a qualified veterinary nurse may have to be both a mentor and a coach within the context of veterinary practice.

Defining the role of the clinical coach

According to Walker-Reed (2016), clinical coaching can be defined in a myriad of ways. For example, Corlett (2000) suggested clinical coaching as enabling personal and professional growth leading to service improvement. Downey (2003) further clarified the role as the skill of aiding the performance, learning and development of others.

Within the context of UK veterinary nursing, the term ‘Clinical Coach’ is used to identify an experienced, qualified professional who undertakes support of student veterinary nurses in their placements (Sibson, 2011). This role involves far more than simply the ‘signing off’ of skills and anecdotal evidence. Furthermore, the author's personal experience would suggest that clinical coaches often form strong bonds with their student, as they may support them for the duration of their training and can thus feel a sense of responsibility for them. While there are elements of coaching within the clinical coach and student relationship, arguably, the role encompasses more of the traits of a mentor. This can occasionally blur boundaries, with the potential for clinical coaches and students alike to become confused regarding the scope of the professional supporting their practice (Sibson, 2011).

Coaching and mentoring for qualified veterinary nurses

The term ‘mentee’ is not limited to a student veterinary nurse. For qualified veterinary nurses wishing to move into more of a leadership role, it is worth considering that mentoring from or shadowing a senior leader can be a great learning opportunity for new or emerging leaders to finetune their own leadership skills (Quinn et al, 2014).

Coaching within veterinary practice should not start and end with the clinical coach role; there is scope for veterinary nurses in leadership positions to turn to coaching in its truest sense in order to assist colleagues to achieve their full potential or improve performance. An example of this is illustrated in the case study in Box 2.

Coaching works by increasing the performance of people. Where a business' success depends on the results of the people who work within it, coaching is a huge opportunity. Starr (2012) suggested that it is no longer enough to be a talented or expert individual, especially where you hold a senior position. This further suggests that organisations want ‘expert individuals’ to be able to develop talent and results from others. This is in congruence with Connor and Pokora (2012) who stated that coaching is increasingly being used by organisations as a tool to promote a culture of learning, where leaders and managers are expected, as part of their role, to coach their staff, who in turn can learn coaching skills so that they may coach others. Staff who coach generally encompass the following traits (Starr, 2012):

Adopting a coaching style

The essence of an effective and successful coaching relationship requires the coaching to be productive and deliver results. Listening, silence and effective questioning are key in this process.

Art of listening

Listening is an art that consists of actively and warmly receiving, understanding and accepting the coachee's thoughts and thought patterns, emotions and reactions, affirmations and doubts, as they are, for what they are (Meta-systeme Coaching, 2018). Listening is neither agreeing nor disagreeing; it is non-judgemental and non-comparative — it is just simple reception (Metasysteme Coaching, 2018). Donner and Wheeler (2009) suggested it is the coach's role to actively listen to what the coachee is saying, as well as to notice what they may not be saying; to probe; to clarify and reflect back to the coachee; and to enhance the coachee's ability to listen to themselves.

Power of silence

This basically equates to knowing how to keep quiet; knowing how not to intervene in the coachee's dialogue; and knowing when not to ask questions. This is often the most difficult concept for a novice coach to grasp, as the need to ‘feel useful’, to show their problem-solving competency or to ‘drive’ the coachee forward quicker to reach the end solution may take over (Metasysteme Coaching, 2018). However, silence creates a space in which the coachee can unfold their frame of reference and explore their personal territory. Donner and Wheeler (2009) suggested that many healthcare workers know what they want to do and be — all they need is a safe place, the time to think, and some support in order to achieve their goals.

Use of questioning

The essence of effective coaching requires the use of appropriate questions to provide structure to the session. Structure can be provided in the form of a coaching model; while not all coaching sessions require the use of a model, they can be a useful focus when a clear goal has been identified, or to aid a novice coach in knowing where to begin (Arnold, 2009).

Coaching models

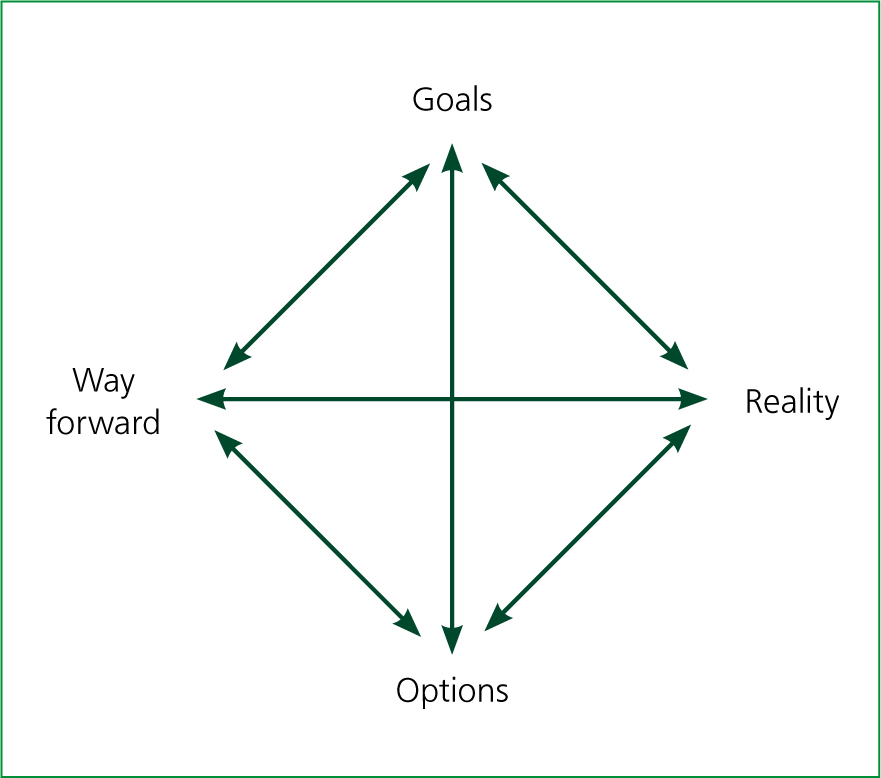

There are a number of models available, with perhaps the most well known one being the GROW model (Whitmore, 1992) (Figure 1). The rationale behind the use of this model is that it is designed to focus attention at the outset on what the coachee wants to achieve from the session.

GROW

GROW is an acronym for:

The coach prepares the coachee by introducing the model and by showing them the process. The coach then asks open-ended questions such as those shown in the sections that follow.

GOAL

The more specific the GOAL defined at the outset of the session, the more successful the session will likely be for the coachee. An example of a question to ascertain the GOAL would be: ‘What would you like to achieve from this session’ or ‘What outcome would you like from this discussion?’

REALITY

What is the REALITY of the current situation? What does the coachee want to change; what influence do they have over their GOAL; what have they done so far; what results have they achieved? An example of a question used to ascertain the REALITY and explore the current situation would be: ‘What is happening at the moment’ or ‘What have you done so far?’

OPTIONS

This is the time to allow the creativity to happen. The coachee should be encouraged to explore as many options as they can — there are never just two! Questions that could be used to generate OPTIONS or courses of action include: ‘What could you do to change the situation’ or ‘What approaches have you seen used in similar circumstances?’

WAY FORWARD

This is the commitment to take action, achieve the GOAL and move forward. It requires determining what is to be done, when, by whom and exercising the will to do it. Useful questions to determine the WAY FORWARD include ‘What are the next steps’ or ‘How will you ensure that it happens?’ When talking a coachee through the steps of the model, it may become apparent that they have no specific goal in mind. In this instance, Arnold (2009) advocated that ‘reality’ and ‘options’ may be better places to start.

Adapted from Pinna Ltd (2012).

SMART goals

Conversely, the initial goal set by the coachee may be too ambiguous; the use of SMART goals can help to provide focus in this instance. Setting SMART goals enables the coachee to clarify their ideas, focus their efforts, use their time and resources productively, and increase their chances of achieving what they wish to achieve.

SMART is an acronym for goals that are:

Obstacles

While being goal-focused is important, Quinn et al (2014) stated that the journey to achieve those outcomes is of paramount importance. Life, however, is not always as simple as agreeing to complete a goal and suddenly finding it has been achieved. Unexpected obstacles are often encountered which require a degree of flexibility and, arguably, tenacity in the approach to goal attainment. Quinn et al (2014) defined the two main sets of obstacles as:

In some instances, continuing to have a barrier/problem may appear more beneficial to an individual than to remove it. Quinn et al (2014) likened this to a person who may sabotage promotion prospects by holding an unresourceful or unhelpful belief in their own abilities because they prefer to have fewer responsibilities.

For veterinary staff who might recognise themselves in these scenarios, it might be useful to attempt the exercise detailed in Box 3. To get the best results from mentoring and coaching in the workplace, staff need to want to participate in the process, not be thrust into it as part of a forced or disciplinary activity. Effective coaching requires individuals to fully engage with the process and to make the most out of sessions by reflecting on them in order to maximise results. According to Quinn et al (2014), coaching, if effective, is not done to you; rather, it is something that you choose and embrace as you move from current to desired state.

Identifying staff who may benefit from coaching/mentoring

Donner and Wheeler (2009) suggested the following as a list of situations for which the services of a coach/mentor may be helpful for nurses within a human healthcare setting. This can be extrapolated to the context of veterinary nursing:

Conclusion

The value of mentoring and coaching within a healthcare discipline cannot be overstated. Each method can add valuable skills to an employee's repertoire; mentoring and coaching help veterinary nurses to engage in conversations and relationships that empower people by facilitating self-directed learning, personal growth, and improved performance (Hattie, 2012).

The further use of mentoring and coaching skills within veterinary practice presents tremendous opportunity for veterinary nurses to meet the challenges of staff retention, professional development of self and others, and the continued provision of quality care.