It has been suggested that most pet cats are likely to be hospitalised or caged at some point during their life (McCune, 2011). Caging a cat leaves them with very little control over their environment, something that is of great importance to cats (Cannon and Rodan, 2016). For most cats, being confined in an unfamiliar environment will elicit negative emotions such as frustration, fear, and anxiety (Bradshaw et al, 2012). This was demonstrated in a study that compared urinary cortisol of 31 cats at home and during hospitalisation, which found a significant increase in cortisol in those samples taken post hospital admission (p<0.001) (Cauvin et al, 2003). This is due to the physiological stress response, which also has an influence on other parameters such as rectal temperature, heart rate and respiratory rate (Soares et al, 2012). In cats, elevated blood pressure as a result of stress from the veterinary environment has been particularly well documented and this is often referred to as the ‘white coat-effect’ (Belew et al, 1999). This can present difficulties in interpretation of such parameters in patients and requires consideration of stress as an influence (Soares et al, 2012). Additionally, stress has been linked to certain diseases, and has been found to slow healing and recovery rate of patients (Levensaler, 2014). Stress appears to be a concern for cat owners too: in a survey of 1111 cat owners, 73.1% believed that their cat became more stressed at veterinary visits following a surgical procedure (Mariti et al, 2016). Additionally, stress is reported to be one of the most common reasons for owners not taking their cat to the veterinary practice at all (Volk et al, 2014). It is therefore in the interest of veterinary professionals to minimise cat stress during hospitalisation.

One way of reducing stress of a confined animal is to provide them with choice (Mills et al, 2013). For cats, it is important to have the choice to retreat from stressors (Cannon and Rodan, 2016). For caged cats, retreating often presents as hiding behaviour (Rochlitz, 2009). Studies have found that when caged but not provided with opportunity to hide, cats can show hide seeking behaviours such as shredding newspaper or attempting to hide behind litter trays (Gourkow and Fraser, 2006; Vinke et al, 2014). This suggests that hiding is a highly motivated behaviour for cats. Despite this, an extensive search of literature failed to find any studies investigating what is sufficient if providing hiding opportunity. Anecdotal evidence suggests that it can be provided using a box or by covering the front of the cage with a towel, and that these methods can reduce stress of a hospitalised cat (Horwitz and Little, 2016; Cannon and Rodan, 2016; Herron and Shreyer, 2014). The efficacy of using a box has been investigated by a number of studies: Skanberg (2014) found that cats used hide boxes 85% more in the first 3 days following environmental change. Kry and Casey (2007) found that cats in a shelter provided with a box used it for 77% of the time and that their Cat Stress Score (CSS) significantly reduced (p<0.0001) by the second day. More recently, cats that were provided with a hiding box showed a reduction in heart rate and respiratory rate after 20 minutes of hospitalisation (Buckley and Arrandale, 2017).

While research into the box as a hiding method has found advantages in terms of stress reduction, at present there is a lack of research into the partial towel cover method. Cannon and Rodan (2016) assert that a partial cover to the cage front gives the cat choice to hide or see out. A towel cover was used by Gourkow and Fraser (2006) to provide hiding opportunity, but this was in conjunction with other enrichment and draped over a shelf structure as opposed to over the cage front. This might also be referred to as a visual barrier. The use of visual barriers has been investigated in captive felis species (Bashaw et al, 2007), but despite advice encouraging its use in the veterinary environment, it appears that the efficacy of the method in domestic cats has not been studied. As such, the objective of this comparative study was to investigate whether providing hospitalised cats with either a box or a partial towel cover to the front of the cage, reduced cat stress levels, and whether each of these methods were sufficient in providing hiding opportunity.

Materials and methods

Facility

The study took place over a 3 month period, at a small-animal first opinion veterinary practice. The study was approved by the ethics committee at Harper Adams University and by the veterinary practice involved. Written owner consent for cats to be involved in the study was obtained at admission. Subjects were housed in a cat only ward, in which the cages did not face or overlook each other.

Subjects

All of the 42 subjects were healthy pet cats that were admitted for routine neutering. All were subject to a clinical examination by a veterinary surgeon. This was carried out once data collection was completed and was followed by administration of premedication. The male to female ratio was even (21:21). Most cats were of no specific pedigree breed, with Domestic Short Haired accounting for 88% of subjects. Cats were between the age of 5 months and 4 years and had a median age of 5 months. None of the cats had been hospitalised before, nor had they experienced a cattery. Previous experience of the veterinary practice differed, with 27 of the cats having visited a veterinary practice before, while 15 had not.

Protocol

Cats were assigned to a cage number and a treatment number by randomisation, in order of admission. Treatments, as shown in Figure 1, were as follows;

Observation and data collection was carried out by a single observer, who was a member of the nursing team and the sole observer for this study. Prior to the study commencing, the observer underwent training to familiarise themselves with the CSS criteria. These criteria were also readily available during data collection. Following training, a small pilot study of three subjects was carried out to further familiarise the observer and to check for observer consistency.

Following admission, behavioural observations were taken for 60 minutes and data were collected every 15 minutes to record the following four criteria;

CSS, location in cage, and use of treatment were all recorded using instantaneous sampling, recording the measures shown at each 15 minute sample point. Hide seeking behaviour was recorded using 1/0 sampling, which recorded whether hide seeking had occurred between each sample point.

Data analysis

Data analyses were conducted using Genstat (18th edition). Data were not normally distributed, confirmed using Shapiro-Wilk test for normality. Given the non-normal distribution, a non-parametric test in the form of Kruskall-Wallis one-way analysis of variance, was used to test for difference between treatments in CSS, location within the cage, use of treatment, and frequency of hide seeking behaviour. A level of p<0.05 was considered to be significant. Additionally, Spearman's rank correlation was used to test for relationships between results of the different measurements.

Results

Location within the cage

Cats spent 71% of their time located in the back section of the cage, compared with time spend at the front (21%) and the middle (8%) (p<0.001). Time spent at the back of the cage for box cats, towel cats, and control cats was 70%, 55%, 87% respectively, but there was no significant difference between these. Towel cats spent significantly more time at the front (39%) compared to the other groups (p=0.012) but this did not correlate to treatment use (rs=0.040).

CSS

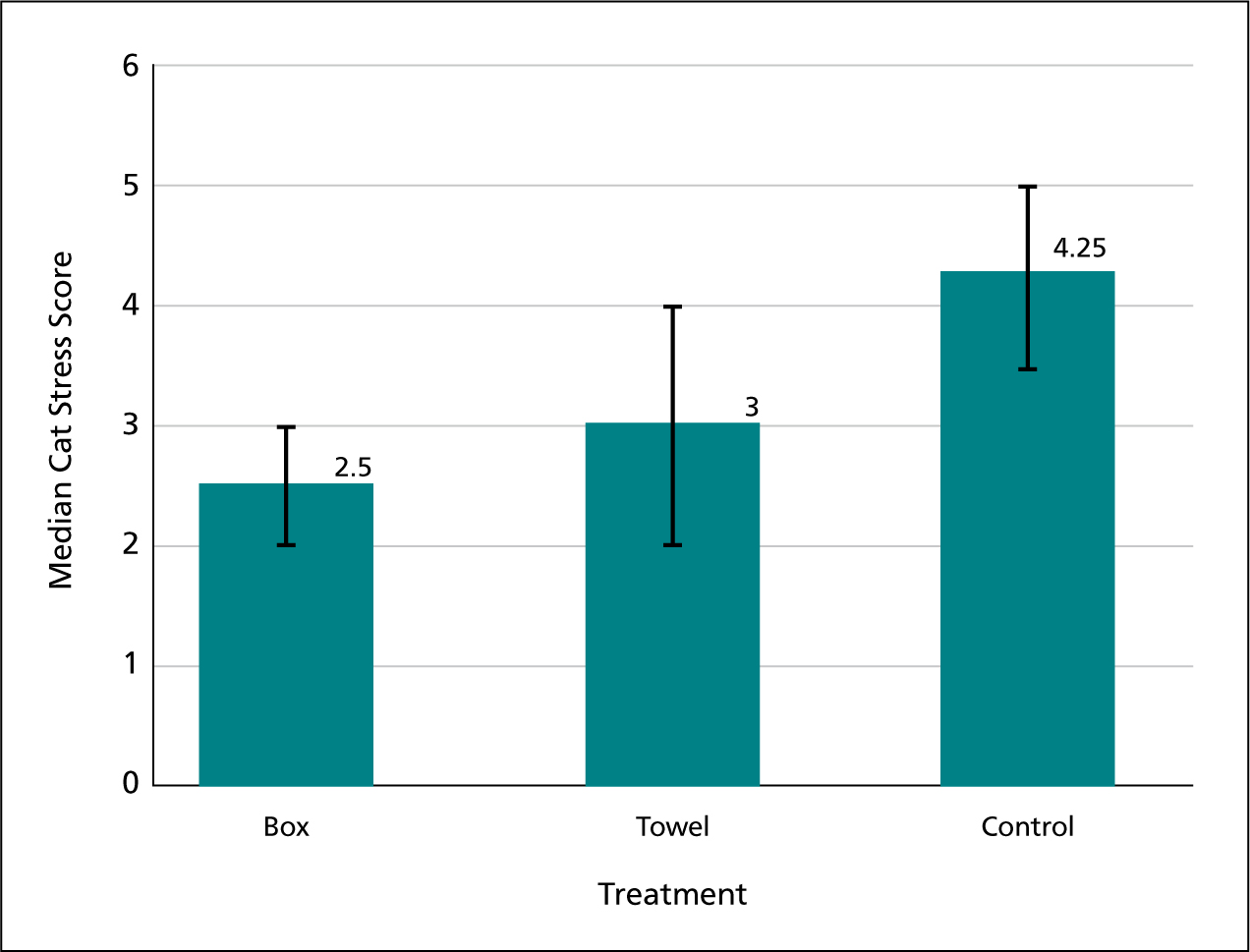

There was a significant difference in CSS amongst the treatment groups (p=0.020). Control cats had the highest median and mean CSS (n=4.25) as shown in Figure 3. There was no significant difference in CSS between control cats and towel cats (p=0.069), or between box cats and towel cats (p=0.406). The only significant difference in CSS between individual groups was between control cats and box cats (p=0.007). Control cats consistently had the highest mean CSS at each of the four sample points. There was a gradual reduction is CSS in all groups, but the difference in CSS at 15 minutes and 60 minutes was not significant in any of the treatments (p=0.112).

Hide seeking behaviour

There was a significant difference in hide seeking behaviour displayed between all treatment groups (p=0.016), with control cats spending the most time displaying hide seeking behaviour (34%) as shown in Table 1. The difference in hide seeking behaviour between control cats and towel cats was not significant (p=0.167), nor was the difference between box cats and towel cats (p=0.113). There was, however, a significant difference in hide seeking behaviour between control cats and box cats (p=0.004).

| Time at front | Time at middle | Time at back | Cat Stress Score | Hide seeking | Treatment use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Box | 21% | 9% | 70% | 2.82 | 2% | 68% |

| Towel | 39% | 6% | 55% | 3.18 | 16% | 30% |

| Control | 4% | 9% | 87% | 3.96 | 34% | - |

| p | 0.019 | 0.622 | 0.116 | 0.020 | 0.016 | 0.027 |

The relationship between CSS and hide seeking behaviour

A positive correlation was found between CSS and hide seeking behaviour within all groups (rs=0.673), and this was stronger when analysed within the control cats only (rs=0.829). Both correlations were statistically significant (p<0.001).

Use of treatment

There was significant difference in treatment use between box cats and towel cats (p=0.027). Cats provided with a box were recorded as being inside the box 68% of the time, whereas cats provided with the towel cover were recorded as using this to hide behind 30% of the time. No relationship was found between use of box and cats being located at the back of cage (rs=0.188).

Discussion

Hide seeking behaviour

An interesting result to come out of this study is the apparent link between the presence of hide seeking behaviour and the CSS, with a positive correlation between the two. Although correlation was present across the total number of cats, the relationship was even stronger when the control group alone was analysed. This is due to a high presence of hide seeking behaviour in this group (n=34%), which is similar to the amount of time that Vinke et al (2014) recorded cats to be hiding behind a litter tray (n=45%). While the correlation is stronger in the control group it was not a complete correlation. The likely cause of this is that some cats scored highly on the CSS, but did not show hide seeking behaviour. One explanation for this may be that the cats that appeared stressed, but did not seek hide, may have been experiencing behavioural inhibition, which can occur when an animal is under extreme stress (Bradshaw et al, 2012). With this in mind, while a high CSS and a high presence of hide seeking behaviour of an individual can be indicative of stress, using the presence or absence of hide seeking behaviour alone would not be a reliable way of assessing stress. This is considered in the descriptions within the CSS, with the symptomatic activity for the highest score of ‘7: Terrorised’, described as ‘motionless’ (Kessler and Turner, 1997).

Skanberg (2014) found a correlation between hiding behaviour and sickness behaviours (such as a reduction in appetite and activity), in the initial period of hospitalisation, whereby cats that hid during this period showed less sickness behaviour (Skanberg, 2014). Therefore, given that stress has been linked to poor health (McCune, 2011), and with consideration of results from both Skanberg (2014) and the present study, it could be suggested that the ability to hide is an important functional coping strategy for cats experiencing acute environmental stress.

Provision of a box

The high frequency of usage of the box as a hiding place suggests that when caged cats are provided with a hiding box, the majority of them will hide inside the box (n=68%). Similar results have been found in both shelter and veterinary practice based studies: Kry and Casey (2007), and more recently Stella et al (2014), found a higher frequency of box usage, both 77%. Differences in results could be explained by how ‘box usage’ is defined. Both of these studies also included cats that were perching on the top of the box, whereas the present study exclusively looked at cats hiding within the box. The CSS of cats provided with a box was significantly lower than control cats, which, if used as an interpretation of the cat's stress level, demonstrates the efficacy of a box as a stress reduction method. This result supports that of Kry and Casey (2007), who also found that cats that were provided with a box had a significantly lower CSS than those that were not.

Provision of a partial towel cover

The partial towel cover appeared to be used for hiding significantly less than the box was used for hiding. However, cats provided with a partial towel cover, did spend significantly more time at the front of the cage in comparison to the other treatment groups. One explanation for this may be that the cats were using the towel cover to hide behind, however the results do not support this. The validity of the towel usage measurement is questionable because of potential observer bias (Martin and Bateson, 2007). There is a greater risk of this occurring in recording towel usage than in recording box usage due to the potential for subjectiveness that comes about from difficulty in identifying whether a cat is using the towel cover or not. The box usage however, is more obvious. Another possible reason for the time spent at the front of the cage is that these cats were more exploratory by nature, which according to Moore et al (2014), may indicate they were less stressed. The CSS of towel cats was less than that of control cats, as was the presence of hide seeking behaviour, which might therefore support this theory. However, neither of these results were significant and as such, cannot prove the efficacy of the partial towel cover in provision of hiding opportunity nor as a stress reduction method.

Limitations

Routine neutering as the reason for hospitalisation of the cats used in this study did present some limitations. First, as the cats were only being hospitalised once, a between-group design was necessary. Should there have been opportunity to hospitalise the cats three times and therefore apply all treatments, a within-subject design might have reduced variability. Second, because observations had to take place before subjects received any premedication or preparation for surgery, there was a limited window of opportunity to collect data, in order not to disrupt the normal running of the veterinary practice. Finally, this study used behavioural measures only and although efforts were made to ensure the validity of these, there is always the potential for subjectivity (Martin and Bateson, 2007).

Conclusion

This study adds to the body of literature on the provision of a hiding box, by further demonstrating that when caged cats are provided with a box they are likely to hide within the box and show less behavioural indices of stress. It has found that there is a relationship between stress of caged cats and presence of hiding seeking behaviour. It has also provided further evidence that when confined to a hospital cage, cats will seek a hiding place. Although the partial towel cover method is recommended in literature, there is little empirical evidence for its use. This study attempted to address this by investigating its efficacy in terms of providing hiding opportunity and reducing stress. The study failed to find significant evidence for either of these effects. As such, conclusions about the efficacy of this method cannot be made and further research is recommended. For application in practice, when considering providing hiding opportunity as a stress reduction method for feline patients, it is important to consider whether what they have been provided with, is actually having the desired effect.