Wound management is an integral part of daily veterinary practice. Wounds should be considered individually with regards to whether they are suitable for closure or not; suturing is the most common way of performing this successfully. Differing suture patterns exist which assist in the closure of wounds dependent on their type (whether they are caused by scalpel blade or trauma, i.e. primary or secondary), size, anatomical location and severity. Appropriate suture material and needle type must also be considered for successful closure and healing. Other wound closure options are available, such as most types of glue, staples or adhesive tape, although these are generally for the most minor of wounds. Dermabond (Ethicon) may be used for larger, more complex wounds. Prior to closure of the wound, any damaged, necrotic tissue must be removed by debridement — whether this be surgical, mechanical or autolytic debridement (Ayello et al, 2008).

In the UK under the Veterinary Surgeons Act 1966 (Schedule 3 Amendment), an RCVS Registered Veterinary Nurse (RVN) or an RCVS enrolled Student Veterinary Nurse (SVN) may perform suturing of wounds on patients when directed by a veterinary surgeon (VS), and the VS is satisfied that they are competent to do so. A list of RVNs deemed competent must be held by the practice. An RVN or SVN may be taught to perform wound suturing by a VS, or by attending an appropriate CPD course.

Suture material

Choice of appropriate suture material and its gauge is dependent on the anatomical location of the wound, the tissue type to be sutured, the tension of the tissue and the length of time the suture is to remain in situ for proper healing of the wound. Smaller gauges of suture offer less trauma to the tissue but are more delicate; knots should be tied gently but firmly to prevent breakage of the suture material (Ansari, 2014).

Suture material may be absorbable or non-absorbable, synthetically-produced or natural, and may be mono or multi-filament. Each will have differing tensile strengths which deteriorate over time. All of these factors should be taken into account when choosing a suture material.

Monofilament materials are made up of a single fibre; multifilament materials consist of more than one fibre which are twisted together. Monofilament materials (and coated materials) provide less tissue drag than multifilament, so are generally less traumatic to the tissue. Multifilament suture material is usually more pliable than monofilament and has less memory, making it easier to handle and provides better knot security. A ‘wicking’ effect however, occurs with multifilament material, making it inappropriate for use in certain situations (such as for skin closure) where it may draw bacteria into the wound from the external environment (Holzman and Raffel, 2015).

Table 1 shows a comparison between these factors for varying (Ethicon) suture material types.

| Suture name/brand | Material | Natural or synthetic | Absorbable or non-absorbable | Construction | Tensile strength | Time of absorption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast-Abs Gut (Ethicon) | Beef serosa/sheep submucosa | Natural | Absorbable | Monofilament | 5–7 days | 21–42 days |

| Plain Gut (Ethicon) | Beef serosa/sheep submucosa | Natural | Absorbable | Monofilament | 7–10 days | 70 days |

| Chromic Gut (coated) (Ethicon) | Beef serosa/sheep submucosa | Natural | Absorbable | Monofilament | 21–28 days | 90 days |

| Vicryl Rapide (Ethicon) | Polyglactin 910 | Synthetic | Absorbable | Multifilament | 50% at 5 days 0% at 10–14 days | 42 days |

| Monocryl (undyed) (Ethicon) | Poliglecaprone 25 | Synthetic | Absorbable | Monofilament | 50–60% at 7 days 0–30% at 14 days | 91–119 days |

| Monocryl (dyed) (Ethicon) | Poliglecaprone 25 | Synthetic | Absorbable | Monofilament | 60–70% at 7 days 30–40% at 14 days | 91–119 days |

| Vicryl (Ethicon) | Polyglactin 910 | Synthetic | Absorbable | Multifilament | 75% at 14 days 50% at 21 days 25% at 28 days | 56–70 days |

| PDS II (Ethicon) | Polydioxanone | Synthetic | Absorbable | Monofilament | 70% at 14 days 50% at 28 days 25% at 42 days | 180–210 days |

| Silk (Ethicon) | Silk | Natural | Non-absorbable | Multifilament | 1 year | N/A |

| Steel (Ethicon) | 316L Stainless Steel | Natural | Non-absorbable | Monofilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Ethilon (Ethicon) | Nylon 6 | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Monofilament | 20% loss per year | N/A |

| Nurolon (Ethicon) | Nylon 6 | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Multifilament | 20% loss per year | N/A |

| Mersilene (Ethicon) | Polyester/Dacron | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Multifilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Ethibond Excel (Ethicon) | Polyester/Dacron | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Multifilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Prolene (Ethicon) | Polypropolene | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Monofilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Polysorb (Covidien) | Lactomer 9-1 | Synthetic | Absorbable | Braided | 21 days | 56–70 days |

| Caprosyn (Covidien) | Polyglytone 6211 | Synthetic | Absorbable | Monofilament | 10 days | 56 days |

| Biosyn (Covidien) | Glycomer 631 | Synthetic | Absorbable | Monofilament | 21 days | 90–110 days |

| Maxon (Covidien) | Polyglyconate | Synthetic | Absorbable | Monofilament | 42 days | 180 days |

| Surgipro II (Covidien) | Polyprolene | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Monofilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Monosof (Covidien) | Nylon | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Monofilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Dermalon (Covidien) | Nylon | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Monofilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Novafil (Covidien) | Polybutester | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Monofilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Sofsilk (Covidien) | Silk | Natural | Non-absorbable | Multifilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Ti-Cron (Covidien) | Polyester | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Multifilament | Indefinite | N/A |

The most commonly used in veterinary practice are poliglecaprone 25, polyglactin, polydioxanone, and polypropolene. An antibacterial version of Vicryl, Monocryl and PDS II have been produced which are coated with triclosan and offer an increased resistance to infection. A study comparing suture materials with and without a triclosan coating showed a 30% reduction in post-operative infection when a triclosan coated suture was used in clean and clean-contaminated surgical wounds (Wang et al, 2013).

Natural suture materials are absorbed via enzymatic degradation, and synthetic suture materials are absorbed via hydrolysis. Catgut can cause a severe inflammatory reaction within the tissue, due to its unpredictability of absorption, whereas synthetic materials have a much more predictable pattern of absorption which is not affected by an inflamed or infected wound (Culp and Burba, 2014).

The gauge of suture material is given by two measures: The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) and metric. Both are defined by the sutures size in millimetres, for example, a 0.2 mm suture would be either 2 (in metric) or 3–0 (in USP), and a 0.3 mm suture would be size 3 in metric or 2–0 in USP (as shown in Table 2). The size of suture chosen should be at least as strong at the tissue it is to hold together, but the smallest possible size to prevent excessive tissue trauma and reduce inflammatory reaction. The tensile strength should last for as long as the wound is likely to take to heal fully (Culp and Burba, 2014).

| Size in mm | Metric gauge | USP gauge for synthetic materials |

|---|---|---|

| 0.02 | 0.2 | 10–0 |

| 0.03 | 0.3 | 9–0 |

| 0.04 | 0.4 | 8–0 |

| 0.05 | 0.5 | 7–0 |

| 0.07 | 0.7 | 6–0 |

| 0.1 | 1 | 5–0 |

| 0.15 | 1.5 | 4–0 |

| 0.2 | 2 | 3–0 |

| 0.3 | 3 | 2–0 |

| 0.35 | 3.5 | 0 |

| 0.4 | 4 | 1 |

| 0.5 | 5 | 2 |

| 0.6 | 6 | 3, 4 |

| 0.7 | 7 | 5 |

| 0.8 | 8 | 6 |

| 0.9 | 9 | 7 |

Suture needles

An appropriate needle should be chosen based on the tissue type being sutured, to minimise trauma and prevent a delayed wound healing time. Needles are available in a variety of lengths, gauges and shapes and are also described by the taper type. Needles may be either swaged-on (attached to the suture material) or non-swaged (have an eye for passing the suture material through) (Schmiedt, 2012). Swaged needles are less traumatic to the tissue than eyed needles, as there is no doubling up of the suture material as there would be in an un-swaged needle when it passes through the needle eye.

The shape of the needle used is defined by the amount of space the surgeon has to manipulate the needle through the tissue. Straight needles are generally used near the surface of the skin where there is more space for hand motion. Curved needles may also be used at the surface, due to ease of passing the suture material, but they are excellent for use when suturing internal tissues in a smaller or deeper area, as the hand motion required is reduced to a mere twist of the wrist to push the needle through. Needles differ in length and for curved needles, the fraction of a circle is also defined. J needles are a combination of both straight and curved needles and can be used close to the skin surface (Aspinall and Aspinall, 2013).

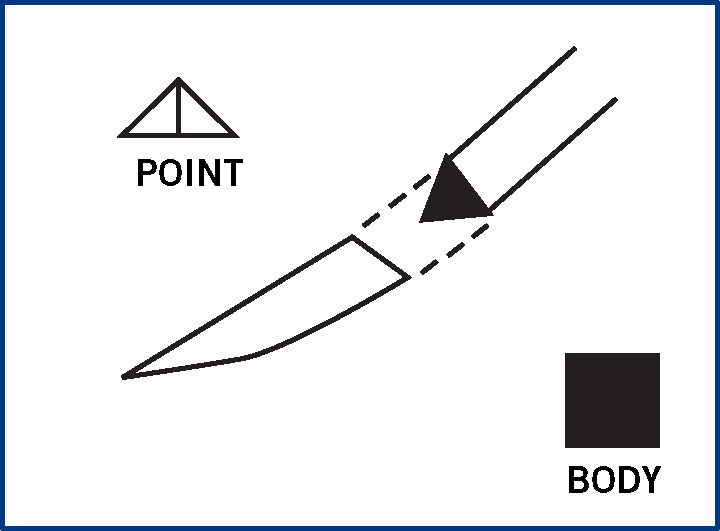

Needles may be cutting (Figure 1) or non-cutting. Cutting needles are usually triangular and have two or three cutting edges. They are used for passing through tougher tissues, such as skin. They may be taper-cut, regular cutting, reverse cutting or spatula point. Reverse cutting are used most often as they are stronger than cutting needles and cause minimal tissue trauma; there is a third cutting edge on the outer curvature of the needle which allows easy penetration of the tissues.

Round-bodied, taper-point and bluntpoint needles are all non cutting. They are less traumatic and are usually used in areas with friable tissue, as blunt needles will cause trauma to tougher tissue. Taper-point needles have a tip that gradually broadens allowing the tissue to separate more easily than a round-bodied or blunt-point needle.

Common suture patterns

If right-handed, the surgeon should suture right to left, or top to bottom. The tissue to be sutured should be held with a pair of forceps (such as Adson-Browns) in the left hand. The right hand should hold the needle-holders, with the needle secured three quarters of the way down its length and pointing in the direction the suture will be placed (Figure 2). When taking a bite of the tissue, the needle should be pushed through using only a wrist action, if it becomes difficult to pass through the tissue, an incorrect needle may have been selected, or the needle may be blunt. The tension of the suture material should be maintained throughout to prevent slack sutures, and the distance between the sutures should be equal.

Suture patterns may be appositional, bringing tissues closely together, or inverting, bringing the tissues together but with the edges turned towards the patient, these are used for creating a proper seal in hollow organs, such as the intestines. Everting sutures turn the wound edges away from the patient, but are not used as frequently.

Continuous patterns

Continuous patterns are the quickest type of suture pattern, used for areas of low tension such as closure of body cavities, muscle layers, adipose tissue, and skin, and are more economical than interrupted patterns. If pulled too tightly, however, the wound may pucker. If any part of the wound breaks down due to failure of the continuous suture, the rest of the wound may be affected and re-open along its length (Fahie, 2012).

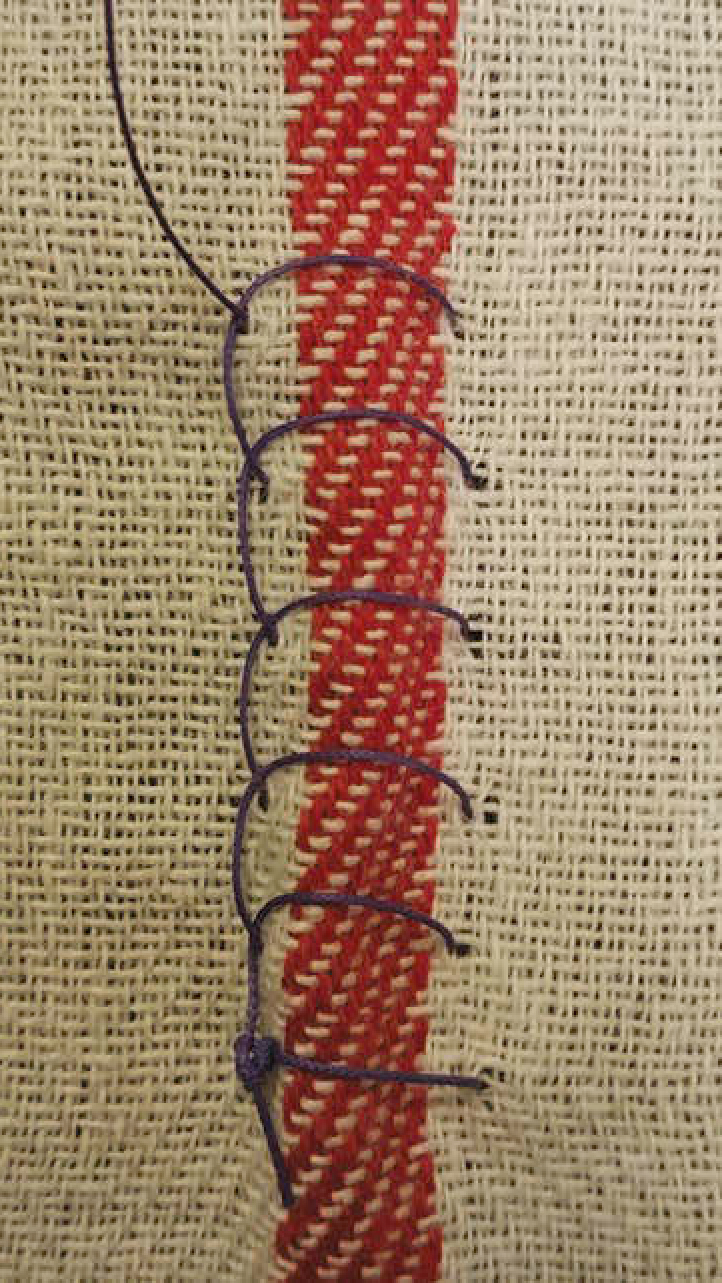

Simple continuous sutures

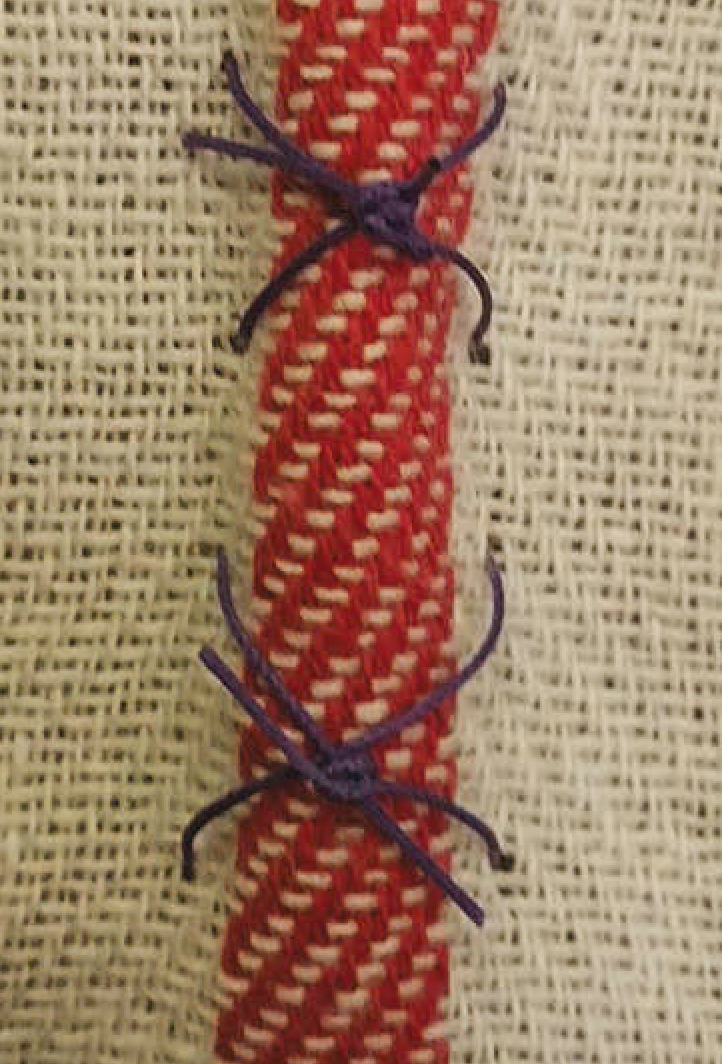

Ford interlocking sutures

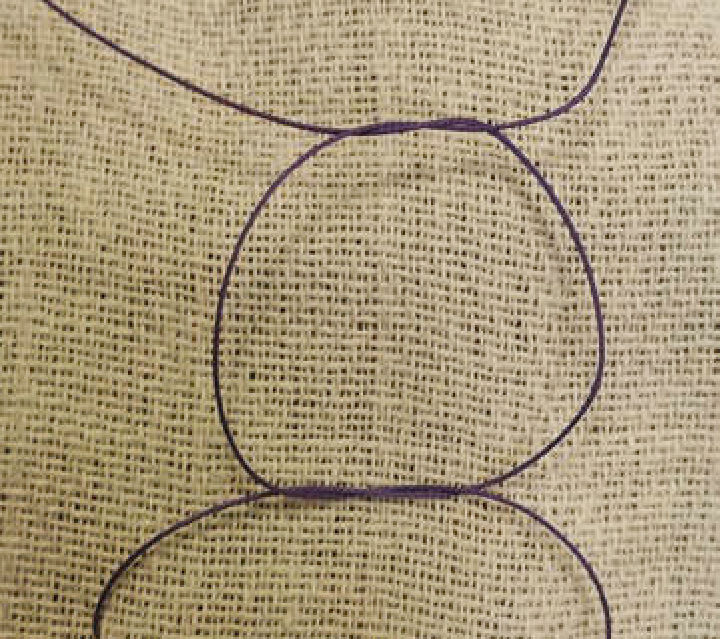

Intra-dermal sutures

Purse-string sutures

Interrupted patterns

Interrupted sutures are used to relieve tension, or in areas where more strength is required. They are not as economical as a continuous suture as a knot must be tied after each suture placement, using a great deal more suture material. Should one of the sutures fail, this will not affect the rest of the sutures placed in the wound.

Simple interrupted

Interrupted cruciate

Horizontal mattress

Vertical mattress

Other patterns

Chinese finger trap

There are various other patterns that exist, but these are mainly for the closure of internal organs (such as Lembert (Figure 11), Connell and Cushing patterns (Figure 12)) for which the veterinary surgeon would be responsible. Connell and Cushing are completed in the same way, with Cushing passing through the deeper tissue layers.

Suture knots

Knot security is defined by the quality of the knot, the technique used, the type of suture used, the body tissue, the moisture content of the wound, and whether infection is present (Culp and Burba, 2014). The smaller the knot, the less tissue reaction, resulting in a more minimal scar (Ansari, 2014). The knot consists of the loop, knot and ears. Knots may be hand tied or tied using instruments, but should not be over tightened to avoid discomfort to the patient, and to make the sutures easier to remove.

Absorbable sutures may be cut fairly short, leaving a length of 2–3 mm. Minimal absorbable suture should be left internally to reduce any tissue reactions that may occur. Non-absorbable sutures should be left longer (around 10 mm) as they will require removal once the wound has healed, usually in 10–14 days (Raffel, 2014).

Square (reef) knot

Surgeon's knot

Buried knot

Aberdeen knot

Newer wound closure techniques

Dermabond

Dermabond Advance (Ethicon) is a new type of tissue adhesive, which studies have shown to increase the strength of a skin wound closure by 75% more than sutures alone. It is available in a pen-style applicator for ease of use and is used for wounds up to 15 cm in length. It is more flexible than other tissue adhesives currently available, and spreads tension along the wound, preventing gaping of the edges which creates a microbial barrier and inhibits Gram positive (MRSA and MRSE) and Gram negative (Escherichia coli) bacteria (Ethicon, 2015a). Bhende et al (2002) showed that there is protection against 99% of organisms responsible for surgical site infections during the first 72 hours post application.

Dermabond Prineo

This is available as a kit, which contains Dermabond adhesive and a polyester mesh tape, to be used for skin closure in conjuction with one another (applying the adhesive to the tape). It may be used to replace subcuticular sutures with a strength similar to that of 2 metric polyglecaprone 25 or to provide further strength to a wound in an area of high tension. It has the same antibacterial properties as Dermabond alone, but may be used for much larger wounds when combined with the polyester mesh. Once the wound has healed fully, the mesh is removed easily from the patient (Ethicon, 2015b).

Stratafix

Stratafix (Ethicon) is a suture material with inbuilt spiral barbs which retract when pulled through the tissue but re-engage and anchor once the suture is in place, avoiding the need for knots (and thus reducing inflammatory reaction to a large amount of suture material). It has a swaged-on needle (with a choice of different needle types) and is available in both absorbable (short-term and long-term) and non-absorbable materials. The unilateral version has a fixation loop at one end, for threading the needle through to secure the material, without the need for a knot. This is used for suturing from one end of a wound to the other, and is suitable for organ closure. The bilateral design has anchors which change direction half-way through the material; this allows the surgeon to close circumferentially or close multiple layers with one length of material. It may be used for complex, curved or irregular wounds, such as abdominoplasty or urethral anastomosis (Ethicon, 2015c).

Conclusion

In the UK, suturing of wounds may be carried out by RVNs or SVNs when under the supervision of the VS. Suturing is the most common technique for the closure of wounds, and is most successful when the appropriate material, needle and pattern are selected for use. Suture patterns should be chosen for the type of wound, its size, anatomical location and whether tension relief is required. A firmly placed knot should begin and end the row of sutures, but not be pulled overly tight, to ensure patient comfort; the more comfortable the patient, the less wound interference.