Veterinary visits can be extremely distressing for feline patients. Lloyd (2017) stated that this is undesirable from a welfare perspective, as well as having a negative impact on immune function and recovery, and an increased risk of injury to staff. Acutely, the stress response is a defensive mechanism and helps to protect the cat from external dangers; however, long-term stress can cause physical and emotional damage. It is also already proven that stress can influence clinical parameters of cats in practice, including heart and respiratory rate, blood pressure and temperature (Horwitz and Rodan, 2018). Quimby et al (2011) added that blood glucose, lactate, platelets and white blood cell counts, among others, can also be affected, making it more difficult to correctly diagnose and treat them as it is unclear whether the changes are as a result of stress or clinical disease. Cameron et al (2004) added that several stress factors contribute to the development of feline idiopathic cystitis, highlighting the negative impact stress can have on feline health.

Stress of feline patients can be minimised by being more considerate of both their environment and the way in which they are handled. The American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP), in collaboration with the International Society of Feline Medicine (ISFM), published feline-friendly handling guidelines (Rodan et al, 2011) detailing how to make the experience as pleasant as possible for the patient, explaining methods from preparing a suitable environment, to restraint and interaction techniques, to chemical restraint. Van Haaften et al (2017) suggested a single pre-appointment dose of gabapentin was effective in reducing stress and aggression in feline patients, while Kronen et al (2006) found feline facial pheromone therapy useful in calming cats in unfamiliar environments. From a simpler, non-pharmacological perspective, there are just as many studies evaluating the methods of decreasing anxiety in feline patients. Abraham (2016) stated placing cats high up off the ground, or even simply covering them with a towel, can all contribute to creating a safer environment for them.

Despite this information being well established, Williams et al (2019) believed that not all veterinary practices are making every effort to minimise the stress of patients and that more could be done to alleviate their anxiety. Hubbard (2016) stated that practices often find barriers to becoming cat friendly, whether these are practical facility restrictions or time constraints. However, The Bayer Veterinary Care Usage Study III: Feline Findings (Volk et al, 2014) found that 78% of veterinary surgeons in the USA believed that better care for felines was one of the most significant missed opportunities for the profession. Most veterinary surgeons recognised that cat owners consider veterinary visits to be stressful for both themselves and their pets, yet Volk et al (2014) stated that 33% of practices do not have staff trained in feline-friendly techniques. Scherk (2015) concurred, stating that many veterinary professionals do not enjoy working with cats as they fear they may be hurt. They believed this fear may be overcome by understanding why cats react the way that they do and learning to identify their cues.

One way of training veterinary surgeons and nurses to recognise signs of stress in cats is through the use of scales and scoring systems. Overall and Denenberg (2021) stated that these are helpful in recognising distressed cats, as well as keeping staff safer and better adjusting their time and methods to fit the needs of each patient. They discussed the practice creating their own scale, urging against making them too detailed so that they do not take too long to use and can be used by anybody. The use of scoring systems is already well established in veterinary practice, with Coleman and Slingsby (2007) stating that 80.3% of veterinary nurses that responded to their survey looking at attitudes towards pain scales believed formal scoring systems are a useful tool in clinical practice. Barratt (2013) concurred, stating that scoring systems encourage frequent evaluations of patients and standardise methods of assessment in practice. Kessler and Turner (1997) published a non-invasive cat stress score (CSS) system when looking at the stress levels of cats in boarding catteries. It is made up of seven levels, with the patient being assigned a score between 1 (fully relaxed) and 7 (terrorised), based on the posture of the body elements, for example, belly, legs, tail, head, eyes, pupils, ears, whiskers, and behaviour, for example, vocalisation and activity. Kessler and Turner's (1997) CSS system has been used successfully in numerous studies; however, does have limitations, as it could be argued that it does not allow for the patient to be assessed ‘holistically’, taking into account other parameters that indicate a patient's emotional state.

Literature review

Many veterinary nurses and veterinary surgeons are not confident in handling cats and recognising why they behave in the way that they do. Goins et al (2019) investigated the ability of veterinary nurses and veterinary surgeons in Ireland in treating common behavioural problems in cats. They surveyed 95 veterinary surgeons and nurses, and while they generally had a good understanding of how to manage problems, some confusion remained, and 36.6% believed they did not receive adequate training in this subject. The study also found that cat friendly initiatives could be further promoted, with 34% of participants stating that they do not provide services to reduce anxiety in feline patients. The range of length of time since graduation between the respondents was large, with some veterinary surgeons graduating in 1990, meaning the results may not be an accurate representation of the current veterinary curriculum. To obtain more accurate results, the questionnaire could have been aimed at those professionals who finished their training within the last 5 years in order to standardise this variable. Goins et al (2019) claimed that the year of graduation made no significant difference to their confidence in addressing feline behavioural problems; however, they provided no statistical test as evidence for this. Dawson et al (2018) agreed that the stress of patients is a reflection on the way they are handled, finding that 50% of practices in their sample size of 41 still routinely scruffed cats, despite it now being well accepted that this is an unnecessary method of restraint, so further study is required to investigate the reason these negative techniques are still in use.

Feilberg et al (2021) conducted research into the prevalence of patient stress-reducing and welfare-enhancing approaches believed to be undertaken in veterinary practice. Of the 1012 veterinary practices they contacted, they received 91 responses. In total, 78% of practices that responded to the survey believed themselves to be doing most of the stress-free techniques and methods available to them; however, only 42.2% of practices included hiding boxes and higher shelves or platforms in kennels. Feilberg et al's (2021) study also found that only 30–41.8% of practices documented stress levels on patients' records and had protocols in place to reduce stress. This was a lot lower than the practice's assessment of pain, and so they suggested this could be due to a lack of staff training on this subject or the perception that mental wellbeing is not as important as the physical wellbeing of patients. Da Graca Pereira et al (2014) concurred, establishing in their study comparing the interpretation of cats' behavioural needs between veterinary professionals and owners that the veterinary professionals who owned cats themselves were statistically significantly better (P=0.019) at recognising stress responses, and thus having the personal experience of owning a cat provides more insight into their behaviour than veterinary training. They stated that animal behaviour should be an integral part of veterinary curricula and there is a lack of sensitivity to minor signs of stress in feline patients.

Broadley et al (2014) investigated the effects of singlecat versus multi-cat home history on perceived behavioural stress in an animal shelter. They used the CSS to evaluate the cats' stress levels and found that their home history had no effect on their stress response, but rather how long they had been in the animal shelter affected how anxious they were. There was a clear correlation between length of stay in the shelter and their stress scores. Those cats who had not had time to acclimatise and had spent less than 4 days in the shelter had a significantly higher stress score than those who had been there longer (P=0.08). Broadley et al (2014) suggested that the CSS influenced the results as it did not take into account individual patient factors and found that age was a confounding factor. The CSS score of the cats decreased with increasing age (P=0.04). They also listed other factors which may influence the CSS allocated to the patient, such as neuter status and sex, which may not be a direct cause of stress. Another point that Broadley et al (2014) made was that there was a huge variation in responses of the CSS depending on who carried out the evaluation and how much time they spent assessing the cat, suggesting the CSS allows for too much inter-rater variability to be completely reliable. It could be argued that a revised CSS system is required, that takes into account factors such as age and neuter status, as well as incorporating other markers that are indicators of stress, such as heart and respiratory rate, in order to have a more reliable method of recognising and assessing stress in feline patients.

Methodology

Aims

The main aim of this research was to improve feline welfare in veterinary practices, by both reducing their stress and making their visits more positive, and by also improving the experience of their owners so that they are more likely to take them to a veterinary practice if necessary. Should the results show that veterinary workers would benefit from a standardised stress scoring system in practice, then this leaves scope for one to be developed.

Research questions

- How confident are veterinary workers in assessing and minimising stress in feline patients?

- Are veterinary professionals receiving sufficient training on recognising and minimising stress of feline patients during their training?

- Are veterinary professionals aware of the Kessler and Turner (1997) CSS system?

- Do veterinary workers feel an adapted, up-to-date stress scoring system has a place in current practice?

Materials and methods

The research was carried out using an online questionnaire, ensuring maximum coverage (Lumsden and Morgan, 2005). Lumsden and Morgan (2005) believed that online questionnaires are generally quicker to answer and submit, and more people are likely to complete them. It is also not personal, so the participants are more likely to give honest answers than with a face-to-face interview. The questionnaire was distributed to participants via the popular veterinary social media groups ‘Vet Nurse Chatter’ and ‘Veterinary Voices’, as these groups contain large numbers of the intended population.

The target audience was student nurses and veterinary surgeons who have completed the animal behaviour module, registered veterinary nurses and veterinary surgeons who have studied or are studying a relevant qualification in the UK that allows them to be registered with the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, in order to obtain responses from professionals who are already qualified and those who are studying the current curricula. This was to allow for a large enough sample size to obtain reliable results and to allow for comparison between the two professions.

Results

Quantitative data

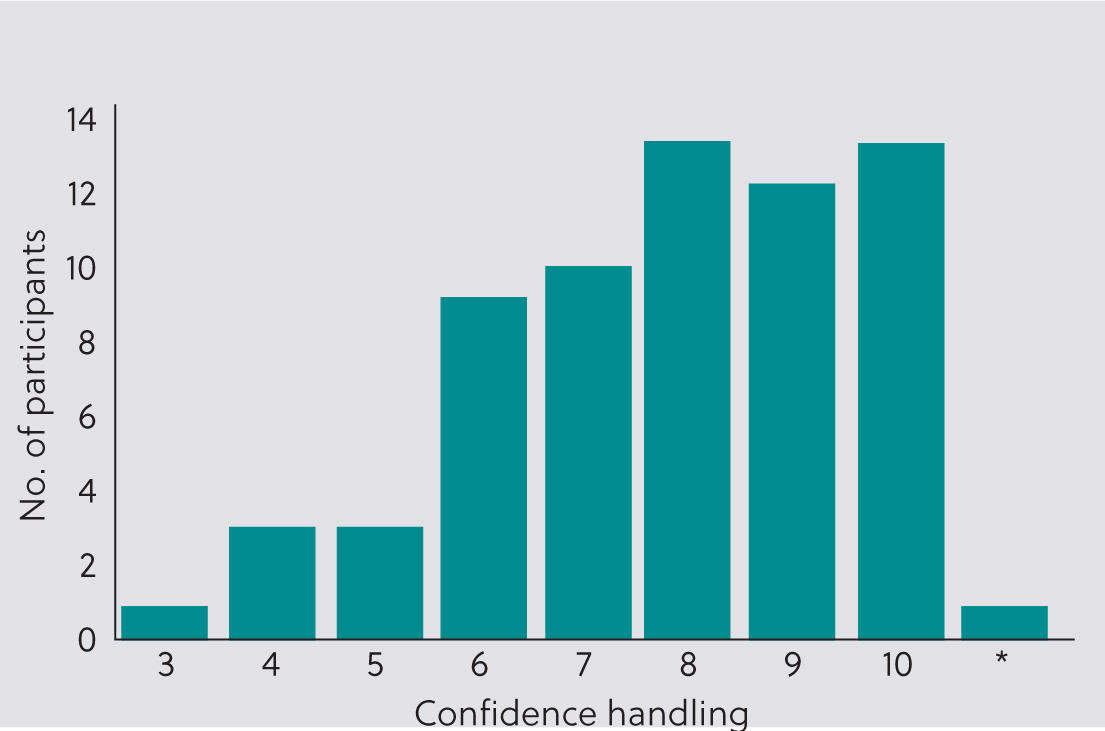

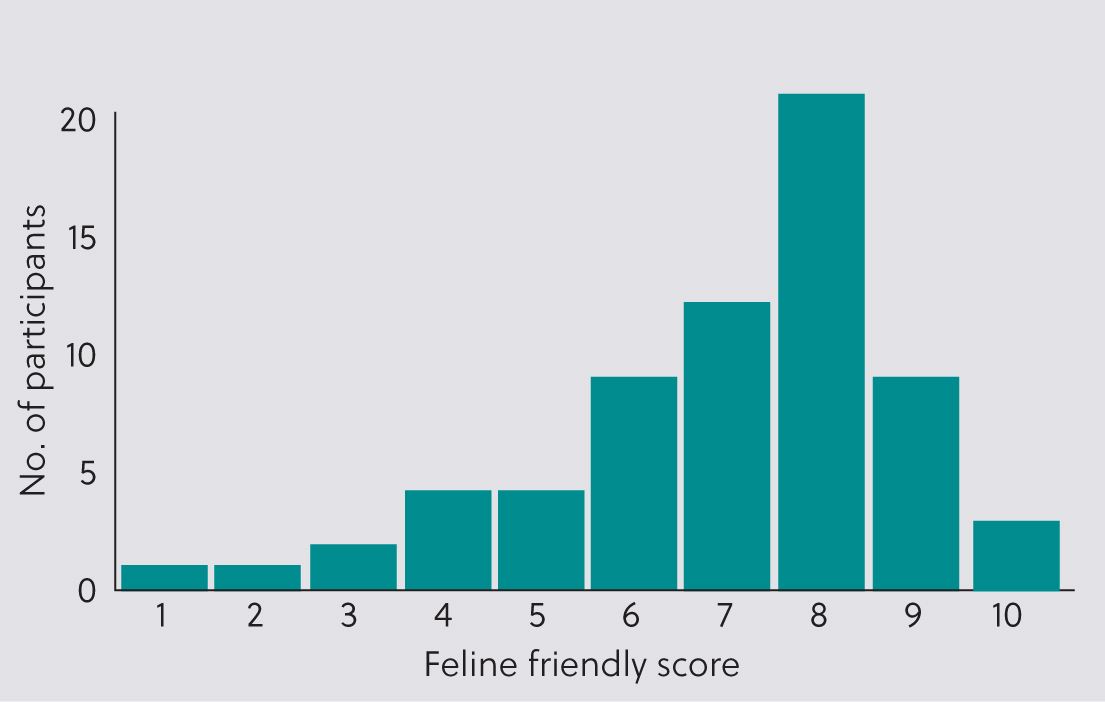

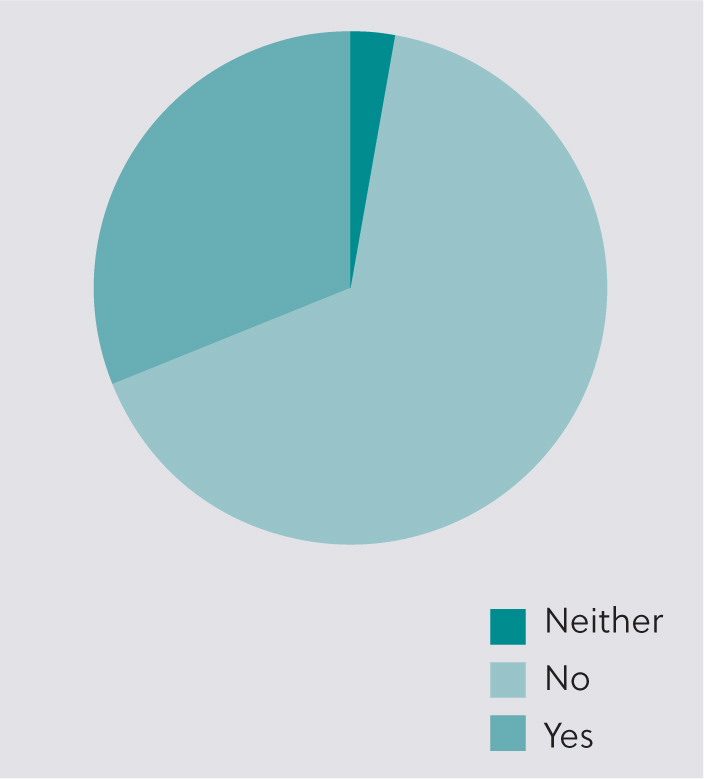

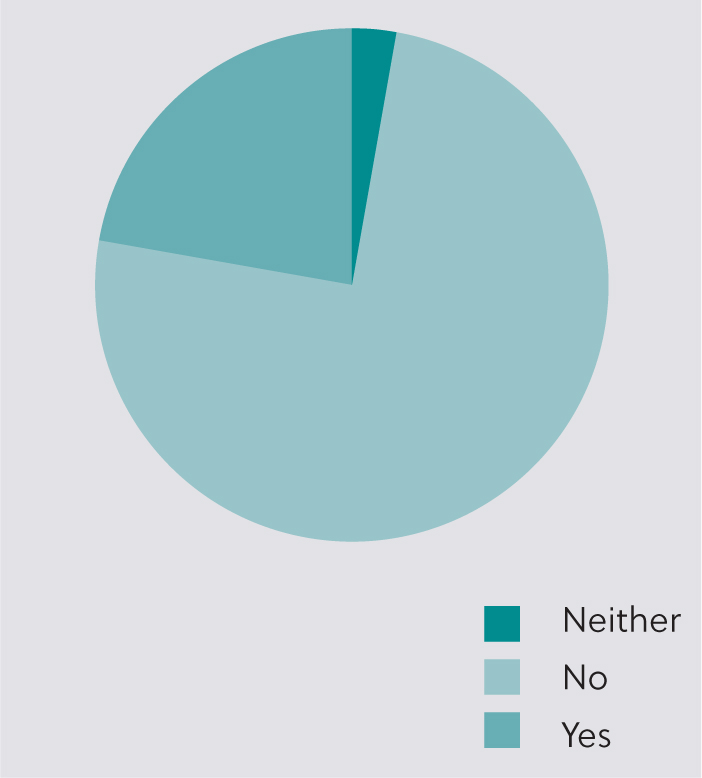

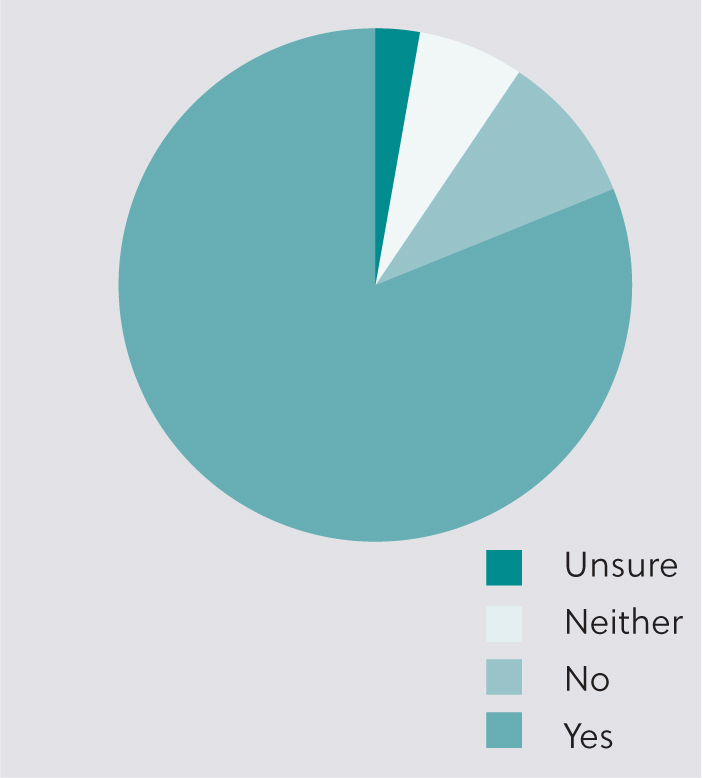

Figures 1 –3 depict how confident the participants were in assessing behaviour in their feline patients, and whether they would feel confident adapting their handling technique and environment accordingly. On a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being not confident and 10 being very confident, the mean of the questions for Figure 1 and 2 was 7.9 and 7.7 respectively. The question regarding how ‘feline friendly’ the participant perceived their practice to be also achieved a mean of 7 (Figure 3). Figures 4–6 display how satisfied the participant was with the training they received, whether they were aware of the CSS and whether they would find it useful. In total, 66.7% of participants stated they were unhappy with the training they had received on feline friendly techniques during their qualification. 75.8% of participants were unaware of the CSS and a further 81.8% believed an updated version would be a useful resource in clinical practice.

Once analysed, there were a number of statistically significant findings in the data. Time qualified was compared with confidence assessing behaviour and confidence handling using a regression fitted line plot test and they achieved P values of 0.000 and 0.018, respectively. Route of qualification was also compared with confidence of handling feline patients. This was done using a Kruskal-Wallis test and achieved a P value of 0.015. A Kruskal-Wallis test was also used to compare whether the participant was aware of the cat stress score with how confident they are at handling feline patients. This produced a P value of 0.007.

Qualitative data

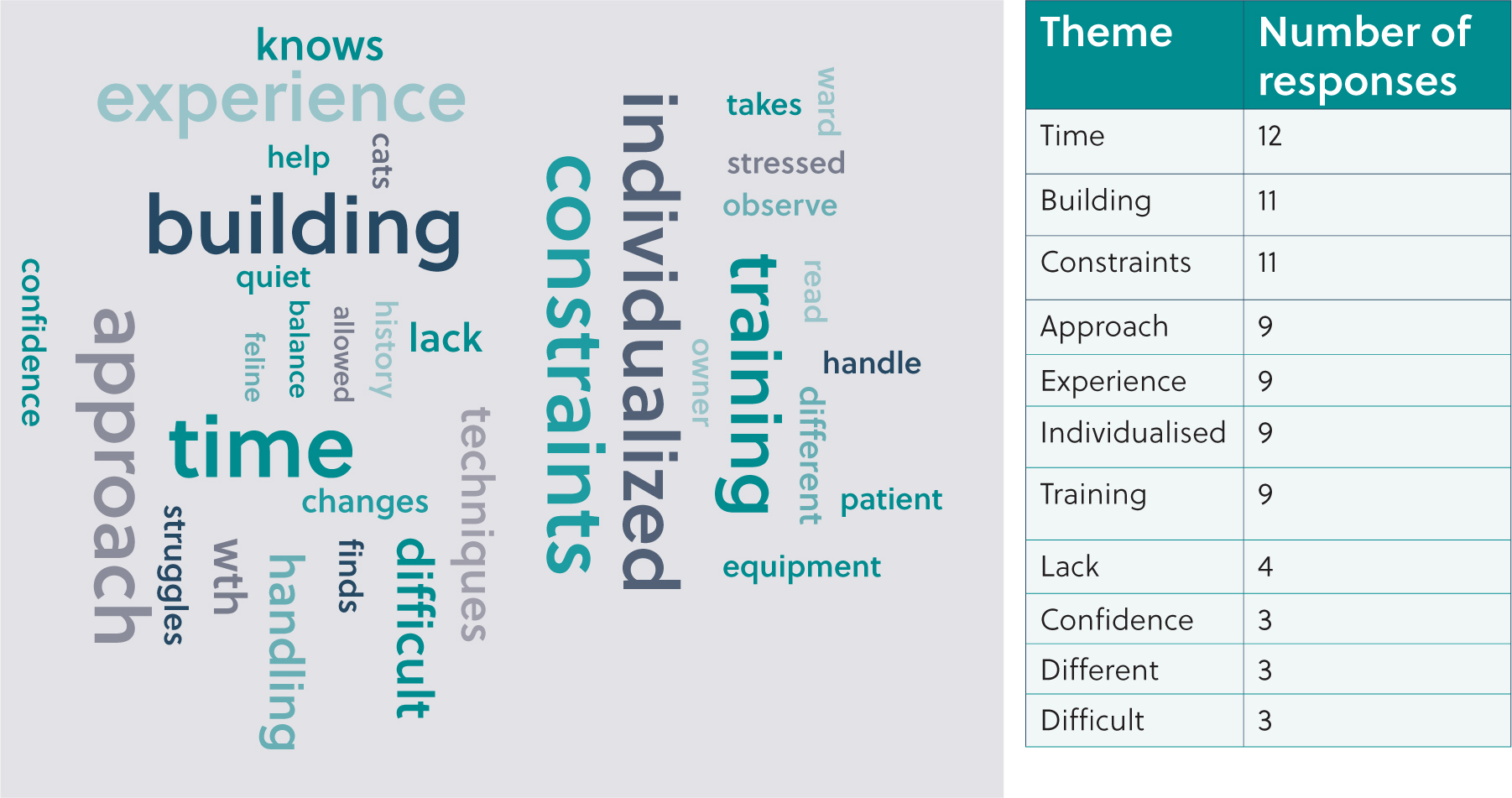

Figures 7 and 8 show a word cloud and charts to display common themes as to why participants felt they were or were not confident in dealing with feline patients. Common themes included lack of awareness by colleagues and time and building constraints. In total, 56% of respondents stated that they felt more confident dealing with cats in practice because of their experience and through handling their own pets at home.

Discussion

Experience

The study showed significant findings when comparing time qualified with both confidence assessing behaviour and confidence adapting handling technique according to patient preference. A fitted line plot regression test was used as ter Braak and Looman (1995) stated that they can be used to explore relations between species and environment. This achieved a P value of 0.000 and 0.018 respectively, suggesting that the longer time qualified the more confident veterinary professionals are with their feline patients. This was supported again in the questionnaire, as when asked why the participants felt they were or were not confident one of the main themes found was ‘experience’, with the words ‘experience’ and ‘ownership’ coming up 20 and 17 times respectively. This corresponds with other studies. For example, Schull et al (2011) found that clinical practice-based training results in considerable improvement in senior veterinary students' perceptions of competence in Day One abilities, concluding that experience leads to an improvement in practical skills. There was also a significant correlation between route of qualification and confidence handling feline patients, which achieved a P value of 0.015, suggesting that despite all routes of qualification having to meet Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) requirements and thus covering roughly the same things, there are discrepancies between courses.

Barriers preventing feline friendly practice

How feline friendly the participant deemed their practice to be achieved a mean score of 7 out of 10 (Figure 3). When explaining their scores, the practice layout, size and time management was a reoccurring factor. Participants who thought they could be more feline friendly stated that they did not have the time or that their consultations were not long enough to do all the methods advised to reduce stress in feline patients. They also stated their practices were not big enough or the layout did not allow for a feline-only ward and/or waiting room. On the other hand, those who thought their practices were good at reducing stress in feline patients had longer consultation times to allow for pheromone therapy, slow handling, acclimatisation and so on, to put their patients at ease. They also had separate wards and waiting rooms to other species. That these factors play a huge part in feline welfare is already well established and was an expected finding in this study, as the International Society of Feline Medicine (Rodan et al, 2011) have published guidelines on how to create a fear-free environment.

Stress scoring system

When questioned on whether they were satisfied with the training they had received on feline friendly techniques during their initial qualifications, 66.7% of participants stated they were not. There was no significant difference between training satisfaction and the confidence of participants in their confidence assessing and handling cats, which given that the results show confidence comes more from experience, is to be expected. In total, 75.8% of participants were not aware of the Kessler and Turner (1997) cat stress score and comparing this with confidence in assessing feline behaviour achieved a statistically significant P value of 0.007. When questioned why, the 81.8% of participants who answered they would find a version of this scale useful in practice, common themes included that it would be better for less feline inclined colleagues, that it would give a baseline of behaviour to go off, and that it would produce a standardised method of assessing all patients. There was no significant difference between whether participants would find a SSS useful in practice and other factors such as feline friendly score, confidence assessing behaviour and adapting handling technique, which was unexpected given the large percentage that stated they would find it useful in practice. This could be due to the small sample size of the study.

Recommendations for further studies

From the results of this questionnaire it is evident that further study needs to be conducted into the difference between the different qualification routes and the syllabus they follow. It could also be beneficial to explore the priorities of veterinary surgeons and nurses in current practice in order to provide more guidelines on how to become feline friendly that still allow them to address their current priorities, for example, less time-consuming methods. Lastly a more in-depth study into what factors participants think would be useful or not useful to include on an updated, more standardised version of a stress scoring system could be helpful.

Recommendations for veterinary practice

From the results, it is evident that most professionals finish their qualification unsatisfied with the training they have received in recognising and reducing stress in feline patients during veterinary visits. The majority have become more confident in this with experience, leaving newly qualified colleagues at a disadvantage. It could be beneficial for practices to do in-house training with new members of staff on this topic. Training could also be carried out to recap the advantages of minimising stress in feline patients, such as the impact it can have on biochemical markers and thus the reliability of the clinical exam and test results. This could make it more of a priority to everybody on the team.

Conclusions

The majority of participants were unsatisfied with the training they had received on assessing stress in feline patients and how to manage this, yet found their practices to be feline friendly. This was thought to be because of participants' experiences with their own cats and further qualifcations they had done. Common issues with being more feline friendly included time and building constraints. Most were unaware a stress scoring system is available, and would find an updated version useful in practice.

KEY POINTS

- Stress is known to have a negative impact on feline welfare, affecting both their emotional state and physiological parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure and blood glucose levels.

- Recognising stress in feline patients and adapting conditions accordingly is not taught in detail on veterinary programmes, with most veterinary professionals relying on experiences with their own cats to learn.

- The most common barriers reported in practice to making a more feline friendly environment are time and building constraints, and a lack of awareness.

- Scoring systems are largely used in clinical practice, yet the cat stress scoring system is not well known or used, and an updated version could be beneficial to aid those not as confident with feline patients.